Presumably, the constellation that introduced us to the night sky is the Big Dipper (and unfortunately, for many of us, it ended there). Let’s begin with this magnificent constellation, which happens to be one of the largest in our celestial sphere, and the recognizable “dipper” is merely a fraction of it. So, why did the ancient Greeks identify a bear in this particular formation? According to their beliefs, the vast Arctic region to the north was home solely to bears. (In Greek, “arktos” signifies bear, hence “arctica” – the land of bears.) Therefore, it’s no wonder that bear imagery embellishes the northern segment of the sky.

One of the ancient Greek myths recounts the tale of these constellations:

Many years ago, there was a ruler named King Lycaon in Arcadia. He had a daughter named Callisto, who was incredibly beautiful. Even the mighty Zeus himself was captivated by her beauty.

In secret, Zeus would often meet with Callisto, despite his jealous wife, the goddess Hera. Their love resulted in the birth of a son named Arkadus. The boy grew up quickly and became an exceptional hunter.

Unfortunately, Hera discovered Zeus and Callisto’s affair. In a fit of anger, she transformed Callisto into a bear. When Arkadus returned from his hunting expedition one evening, he found a female bear in his home. Unaware that it was his own mother, he reached for his bow and arrow. However, Zeus, being all-knowing and all-powerful, grabbed the bear by its tail and lifted her into the sky, where she became the constellation known as the Big Dipper. As Zeus carried her, the bear’s tail stretched out.

Now, located between the Big Dipper and Volopassus constellations, there exists the Hound Dogs constellation, which was introduced by Jan Hevelius. This constellation seamlessly integrates into the ancient Greek myth, where the hunter Volopassus is depicted as keeping the Hound Dogs on a tether, always prepared to attach them to the enormous Dipper.

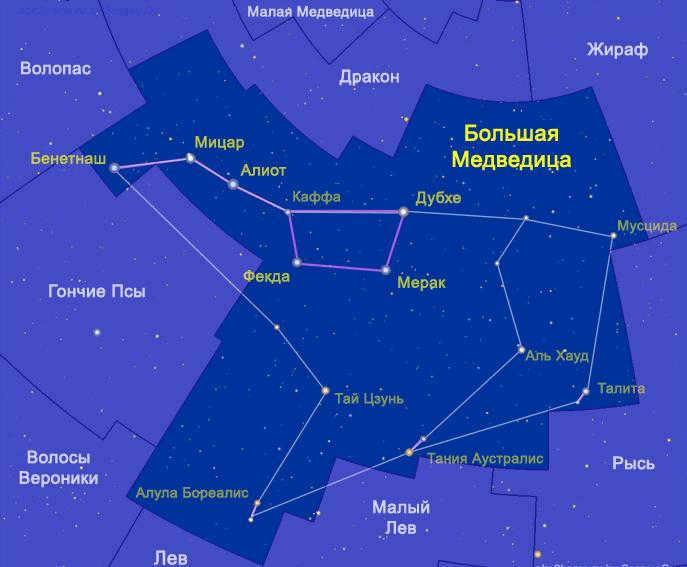

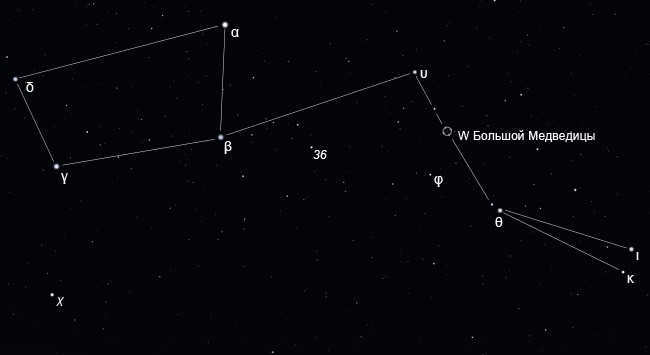

Big Dipper

The Big Dipper constellation is renowned not only for its ease in locating Polaris in the night sky but also for the abundance of intriguing celestial objects that can be observed using simple amateur instruments.

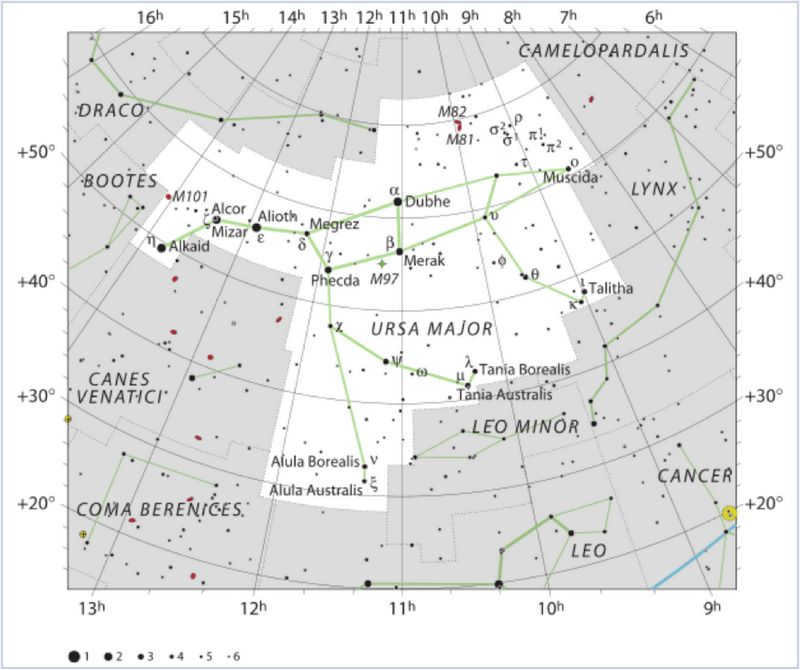

Take a look at the central star in the “handle” of the Big Dipper – ζ, it is one of the most well-known binary stars – Mizar and Alcor (these names are of Arabic origin, like the majority of star names, and they translate to Horse and Rider). These stars are relatively distant from each other in space (such pairs are referred to as optical binaries), but the brighter star, Mizar, can also be observed as a binary through a telescope. In this case, the stars are truly connected by gravitational forces (physical binary) and revolve around a shared center of mass. The brighter star has a luminosity of 2.4 m, while its companion star has a magnitude of 4 m and is situated 14″ away. However, that’s not all – each of these stars is also a binary system, but these pairs are so close together that they cannot be distinguished even with the largest telescopes, and only spectral observations can identify their duality (these stars are recognized as spectroscopic binaries). Therefore, Mizar is a quadruple star (excluding Alcor). In this one location, we can observe examples of all types of binary stars simultaneously.

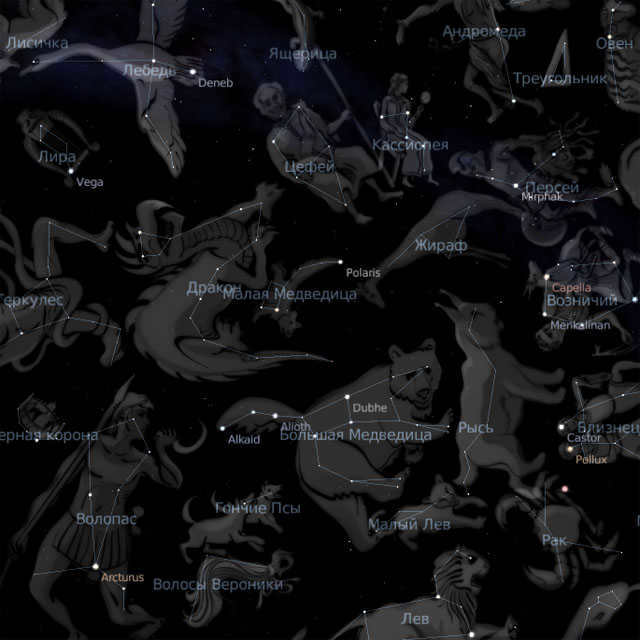

The arrangement of stars known as the Ursa Major constellation, commonly referred to as the Big Dipper, can be observed in the night sky. (Simply hover your cursor over each individual star to reveal a corresponding photograph of the celestial body.)

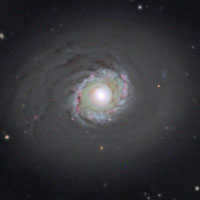

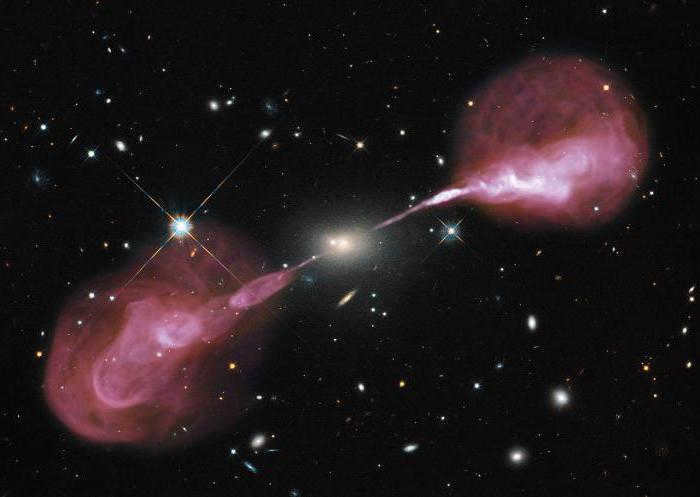

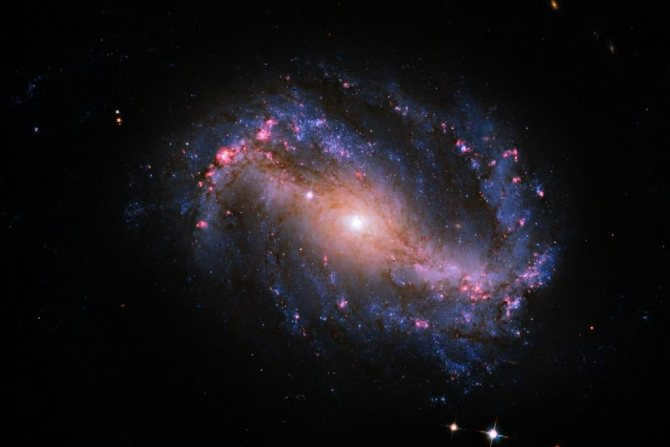

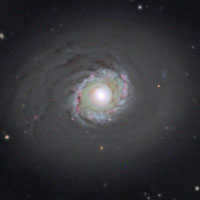

Located on the “neck” of the Big Dipper, we can observe a fascinating duo – M81 and M82 galaxies. While they can be seen through small telescopes, the most intriguing features become apparent with instruments that have a lens diameter of at least 150mm. M81 presents itself as a regular spiral galaxy, while its northern counterpart, M82, is an exquisite example of an irregular galaxy. The images reveal a galaxy seemingly torn apart by a colossal explosion. However, these intricate details cannot be observed visually. Nevertheless, the dark patch in the galaxy’s center is relatively easy to spot.

Within the same telescope’s field of view, slightly to the south of the “bottom of the bucket” and near β of the Big Dipper, we can also catch a glimpse of two more celestial wonders – the M108 galaxy and the M97 “Owl” planetary nebula.

The Little Dipper

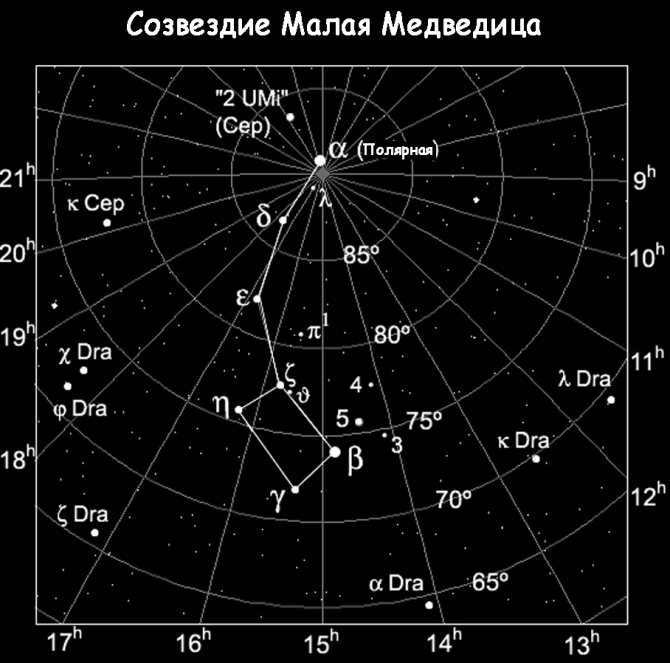

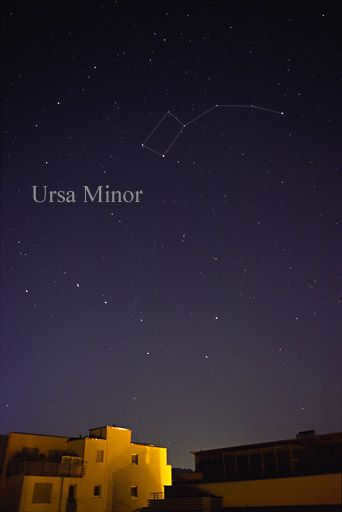

One of the only distinguishing features of this small constellation is Polaris. Presently, it is situated quite near the pole – at a distance of just over 40″ (though, of course, everything is relative, as this distance is noticeably larger than the visible diameter of the Moon). This position of Polaris will not remain constant – the celestial pole is shifting in the sky (a phenomenon known as precession) and in approximately one hundred years, the pole will slowly start to move away from it. (you can find more information about precession )

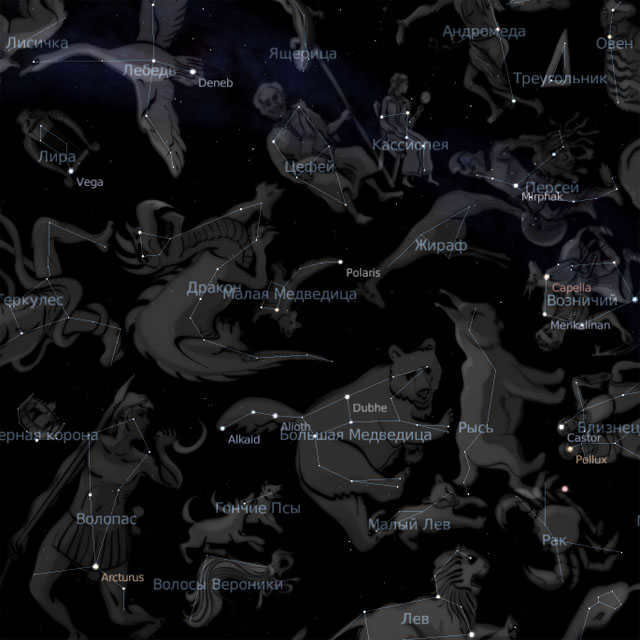

The constellations of Ursa Minor and Draco. (hover your mouse over an object to view its photo)

Dragon

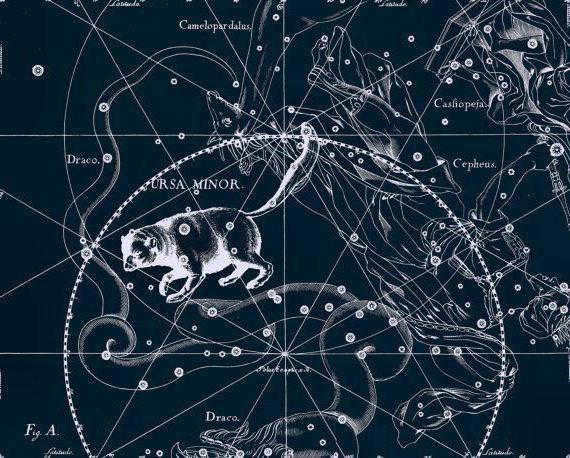

This constellation forms a distinctive chain of stars encircling the Little Dipper. According to Greek mythology, the Dragon is the creature slain by Hercules, who guarded the entrance to the Garden of Hesperides.

One of the major highlights of the constellation is the remarkable planetary nebula known as the “Cat’s Eye” NGC6543. Interestingly, it is positioned towards the pole of the ecliptic, approximately 3000 light years away from the Sun. While it may be small in size, it can be easily observed through moderate-sized telescopes. Unfortunately, the intricate details of the nebula, which earned it its name, can only be fully appreciated through photographs.

This article provides a summary of the constellation known as the Little Bear, which can be found in the northern hemisphere.

The Tale of the Little Bear Constellation

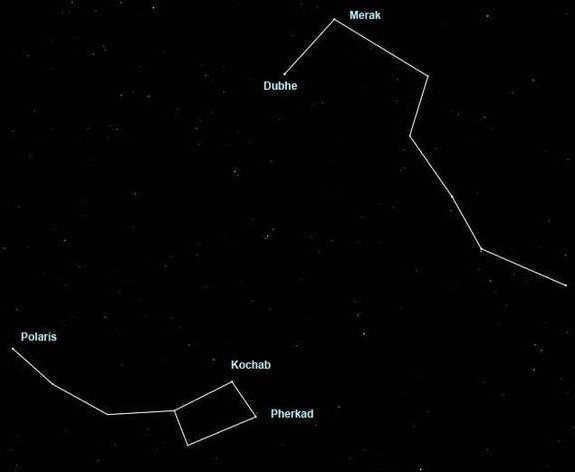

The constellation of the Little Bear shares a close connection with the Big Dipper, not just through ancient tales and folklore, but also through its physical proximity in the vastness of the night sky. It extends from the line of stars that form the handle of the Big Dipper, specifically Merak and Dubhe.

Myth of the Little Bear constellation

The tale of the Little Bear constellation is intertwined with Callisto, the daughter of the Arcadian king. Callisto possessed exceptional beauty and captivated the mighty Zeus. Taking on the guise of Artemis, the goddess whom Callisto served, Zeus approached her in this cunning manner. Eventually, Callisto bore a son named Arcades. Hera, the jealous wife of the ruler of Olympus, discovered this affair and transformed the lovely servant girl into a bear as punishment.

As the boy grew older, he developed into a skilled hunter. While out hunting a wild creature in the forest, he encountered a bear and took aim at her with his bow. However, Zeus, who always kept a close eye on his favorite, redirected the arrow. He transformed Arkad into a young bear and brought him, along with Callisto, up to the heavens. But Hera was not content with this outcome. She approached Poseidon, her brother and ruler of the seas, and convinced him to prevent the celestial bears from entering the kingdom of the sea. As a result, the Little and Big Dipper, positioned in the northern and central latitudes, never dip below the horizon.

Because the ancient Greeks considered the bear to be a rare and exotic animal, they represented it in the sky with a unique, elongated tail that the actual bear does not possess. Another name for this constellation is Kinosura, which translates to “dog’s tail”.

How many stars are there in the constellation of Ursa Minor?

Compared to other constellations, Ursa Minor is relatively small. Located in the northern hemisphere, it contains only 25 visible stars under ideal conditions with the naked eye. Among these stars, the three brightest are known as α, β, and γ.

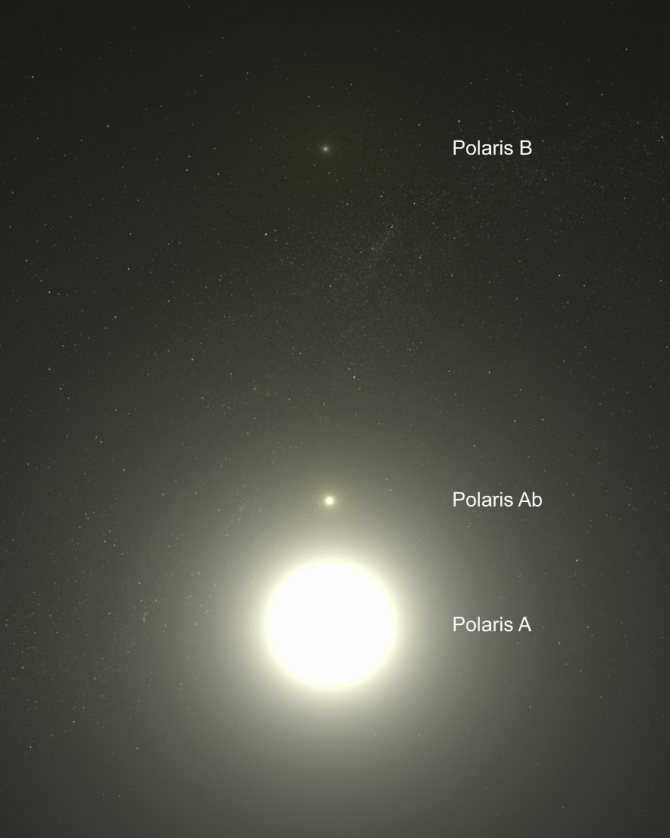

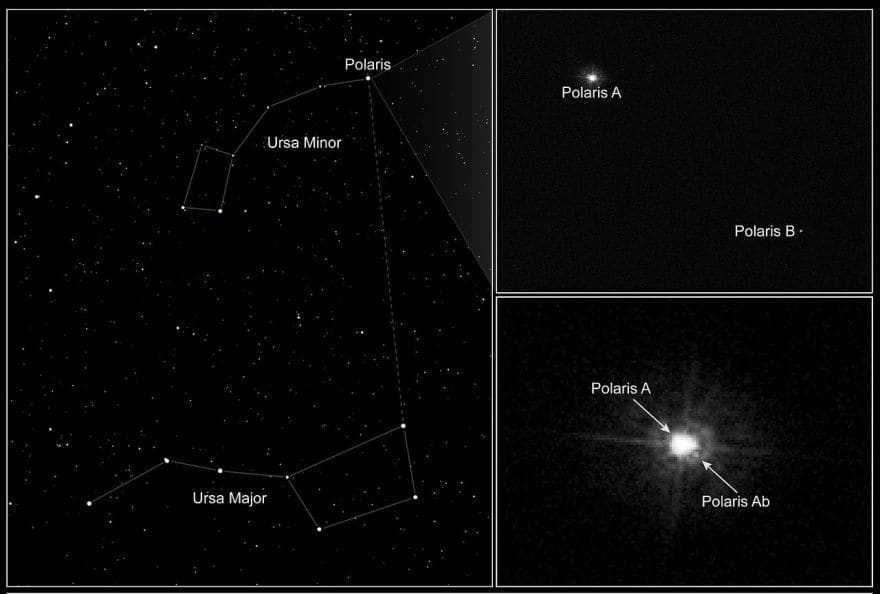

The brightest star in Ursa Minor is Polaris (α), often referred to as the North Star. It is in close proximity to the celestial pole and remains nearly stationary. The other stars appear to “orbit” around Polaris. Polaris is classified as a giant star, significantly hotter than the Sun, and it has two companion stars.

Kohab (β) of Ursa Minor is nearly as bright as Polaris. It has an orange hue and a spectral structure. Despite being 40 times larger than the Sun, Kohab is cooler than it. Additionally, it is many times more luminous than our own star.

The star Ferkad (γ) is also classified as a giant star. It is hotter than both Kohab and Polaris, but due to its much greater distance, it appears less bright compared to them.

The three most brilliant stars in Ursa Minor together form the constellation known as the Guardians of the Pole.

We trust that this account of the Big Dipper has expanded your knowledge of astronomy. Feel free to share your thoughts on the Big Dipper using the comment form below.

Even individuals who are not well-versed in astronomy are familiar with how to locate the Big Dipper in the night sky. As a result of its close proximity to the Earth’s North Pole, in the middle latitudes of our country, the Big Dipper is a constellation that never sets, meaning it can be observed in the sky at any time from dusk to dawn throughout the year. However, the position of the dipper in relation to the horizon changes throughout the day and throughout the year. For instance, during the short summer nights, the ladle of the Big Dipper gradually descends from the west to the northwest, with the handle of the ladle pointing upwards. On dark August nights, the seven bright stars of the dipper can be found quite low in the northern sky. In the autumn, the dipper starts to rise above the northeastern horizon closer to dawn, and its handle appears to point towards the sunrise. In early December evenings, the Big Dipper is visible low in the north, but during the long winter night it rises high above the horizon by morning and can be observed almost directly overhead. Towards the end of the winter season, as darkness sets in, the dipper of the Big Dipper is visible in the northeast with the handle pointing downwards, and by morning it shifts to the northwest with the handle pointing upwards. It is logical that due to its widespread recognition and excellent visibility on clear evenings (or nights), the dipper of the Big Dipper serves as a starting point for locating other constellations, including the Little Dipper, which features perhaps the most famous star in the northern hemisphere, Polaris. Despite its fame, Polaris is a star that few individuals who are unfamiliar with the mysteries of the night sky have seen with their own eyes. It is comparable in brightness to the stars of the Big Dipper, but all the other stars in the “small dipper” of the Little Dipper, except for one additional star in the southern part of the constellation, are much fainter and may not be visible in brightly illuminated city skies. Therefore, for those seeking to acquaint themselves with the starry sky, it is preferable to choose an observation site outside of large urban areas or within a forest park zone.

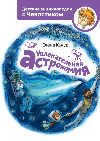

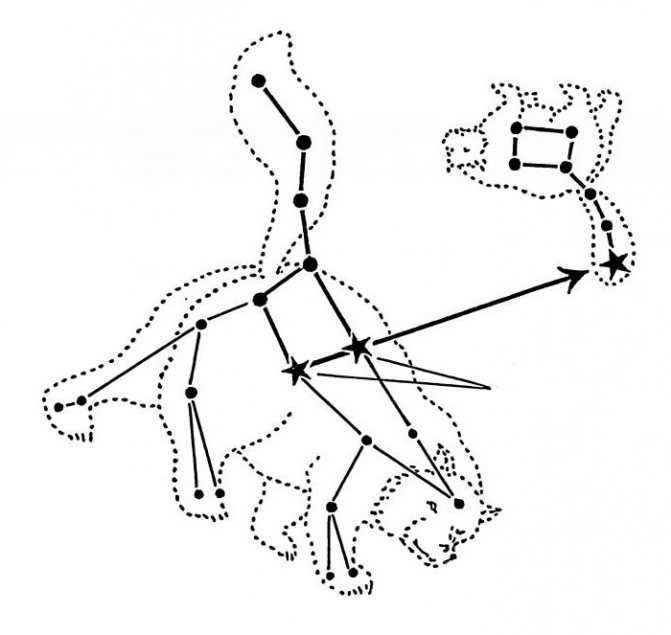

Let’s start our introduction to the celestial sky. Today we will become acquainted with four constellations in the northern sky: the Big Dipper, the Little Dipper (which includes the famous Polaris), the Dragon, and Cassiopeia. These constellations are considered non-setting due to their proximity to the North Pole in the European region of the former USSR. This means that they can be observed in the night sky on any day and at any time. Our first step is to locate the Big Dipper, a well-known formation. Have you found it yet? If not, remember that during summer evenings, the dipper can be found in the northwest; in autumn, it is in the north; in winter, it is in the northeast; and in spring, it is directly overhead. Now, take note of the two outermost stars of the Big Dipper (see diagram). If you mentally draw a straight line through these stars, the first star you encounter, which is comparable in brightness to the stars in the Big Dipper, is Polaris, part of the Little Dipper constellation. Using the map provided, try to locate the other stars in this constellation. If you are observing from an urban area, it may be difficult to see the stars in the “little dipper” (an unofficial name for the Little Dipper constellation) as they are not as bright as the stars in the “big dipper”. It is recommended to have binoculars on hand to aid in this observation. Once you have located the Little Dipper constellation, you can attempt to find the Cassiopeia constellation. Personally, I initially associated it with another ladle, but it more closely resembles a coffee pot. Look at the second-to-last star in the handle of the Big Dipper. Next to this star, you will notice a faint star that is barely visible to the naked eye. The bright star is called Mizar, and the neighboring star is known as Alcor (here is an illustration of iconic Soviet telescopes for astronomy enthusiasts, produced by the Novosibirsk Instrument-Making Plant (NPZ)). It is said that Mizar translates to “horse” in Arabic, while Alcor represents the “rider”.

Now that we have found Mizar, mentally draw a straight line from Mizar through Polaris and continue the same distance. You will then come across a relatively bright constellation in the shape of the Latin letter W (see image). That is Cassiopeia. Doesn’t it resemble a coffee pot?

After Cassiopeia, we will attempt to locate the Dragon constellation. As depicted in the image at the top of the page, it stretches between the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper, extending further towards Cepheus, Lyra, Hercules, and the Swan. We will discuss these constellations in more detail later on. However, once you have gained some basic experience in navigating the night sky, try using the diagram provided above to locate the Dragon constellation in its entirety.

Now you have the ability to locate constellations such as the Big and Little Bears, Cassiopeia, and the Dragon in the sky. By consistently observing these constellations on clear evenings, you will soon become adept at distinguishing them from the rest of the starry sky, making it easier to locate other constellations!

For those aspiring stargazers who wish to continue exploring the wonders of the celestial realm even after mastering all the constellations, we suggest keeping an observation log. It’s important to record the date and time of your observations, as well as sketch the position of the constellations in relation to the horizon. Additionally, try to replicate the precise arrangement of the bright stars within each constellation on the celestial sphere, and make an effort to include even the faintest stars on your homemade “star maps.” These sketching skills will prove invaluable once you become proficient in the language of the night sky and start using a telescope (or binoculars) to observe other celestial objects. Furthermore, it’s always a pleasure to revisit an old observation journal, as it brings back a flood of delightful memories!

Questions regarding the initial assignment:

1. During your observations, where was the constellation Cassiopeia located in the sky?

2. Where was the handle of the Big Dipper located in the sky?

3. Could you see Alcor with your naked eye?

4. Keep a record of your observations (for example, in a regular notebook), noting the position of the constellations you are familiar with from the first task above the horizon in the evening, at night, and in the morning. This will allow you to personally witness the daily rotation of the celestial sphere. Try to depict the appearance of the constellations in your journal as accurately as possible, and label even the faintest stars. Don’t limit yourself to just the familiar constellations. Also draw the parts of the starry sky that you are not yet familiar with.

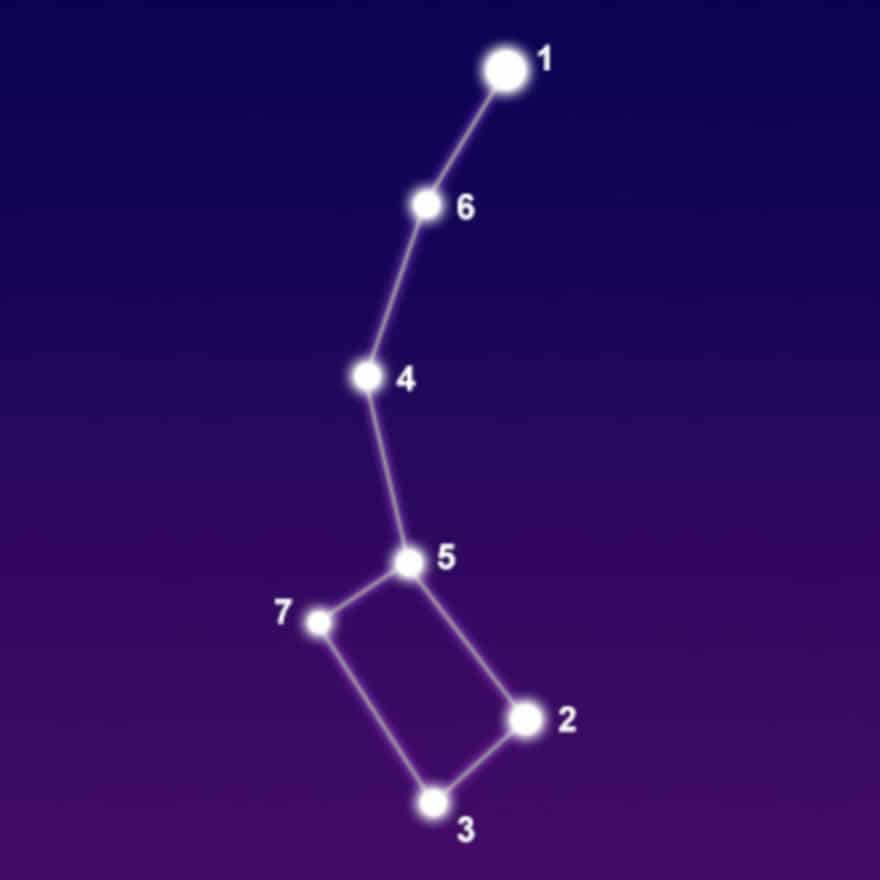

The constellation known as the Little Bear can be found in the northern hemisphere and is visible to the naked eye. It consists of approximately forty stars. Currently, the North Pole is located within the Little Bear, less than 1 degree away from Polaris. The Little Bear is also commonly referred to as the Little Dipper due to its seven stars resembling a small ladle. The brightest star in the constellation, located in the “handle” of the ladle, is Polaris (also known as alpha of the Little Bear) with a magnitude of 2.0. The second brightest star is Kohab (also known as beta of the Little Bear) with a magnitude of 2.1. Between the years 2000 B.C. and 500 A.D., Kohab served as the polar star and was known as Kohab zl-Shemali, which translates to “Star of the North” in Arabic.

Ferkad, which is the gamma star of the Ursa Minor constellation, has a magnitude of 3.1″. It is part of a pair known as the “guardians of the pole” along with the Ursa Minor constellation itself, as they orbit around Polaris in a protective manner. If you look through a telescope at a distance of 18 arc seconds from Polaris, you can spot Ferkad’s companion star, which has an apparent magnitude of 9.

Polaris used to be classified as a variable Cepheid star, meaning its brightness would change by about 0.3 magnitudes over a period of approximately 4 days. However, in the 1990s, the fluctuations in its light suddenly ceased.

Among the celestial objects located in the Ursa Minor constellation are two spiral galaxies, namely NGC 5832 and NGC 6217.

Image: Spiral galaxy NGC 6217 in the Ursa Minor constellation.

Locating the constellation in the night sky

The constellation can be seen in latitudes ranging from -10° to +90°. The optimal conditions for observing it are during the late summer, autumn, and winter. It remains visible throughout the year in Russia. Adjacent constellations include Draco, Camelopardalis, and Cepheus.

The Ursa Minor, commonly known as the Little Bear, presents a challenge in its search due to the fact that only the two outermost stars of the Big Dipper are bright enough to be visible to the naked eye. However, one can find guidance in Polaris, which can be located using the Big Dipper. In autumn, the latter can be found to the right and lower than its counterpart.

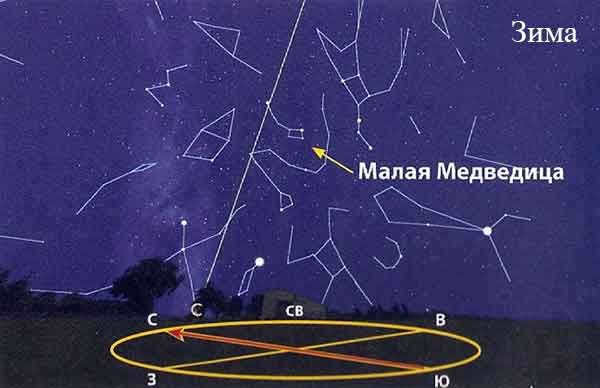

During the winter months, the Little Bear constellation is positioned in a tilted manner, with its dipper facing downward and pointing towards the northeastern side of the horizon. On the right and at a higher position, the Big Dipper can be observed. Additionally, to the left of the Little Bear, the Cassiopeia constellation is clearly visible.

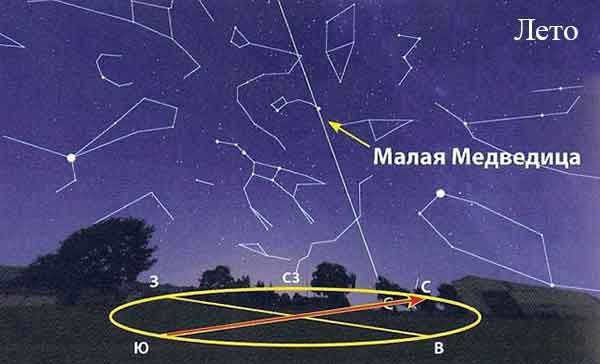

In the summer, around midnight, the Little Dipper takes up a position above its older sister constellation. This inseparable pair is easily seen on the right side, with Cassiopeia positioned above and Perseus slightly lower. At a considerable distance to the left, the Magpies and the Northern Crown can be observed.

The constellation of Ursa Minor, also known as the Little Bear, is a circumpolar constellation located in the Northern Hemisphere of the sky. It covers an area of 255.9 square degrees and contains 25 stars that can be seen with the naked eye. Ursa Minor is currently home to the North Pole, which is situated at an angular distance of 40′ from the constellation.

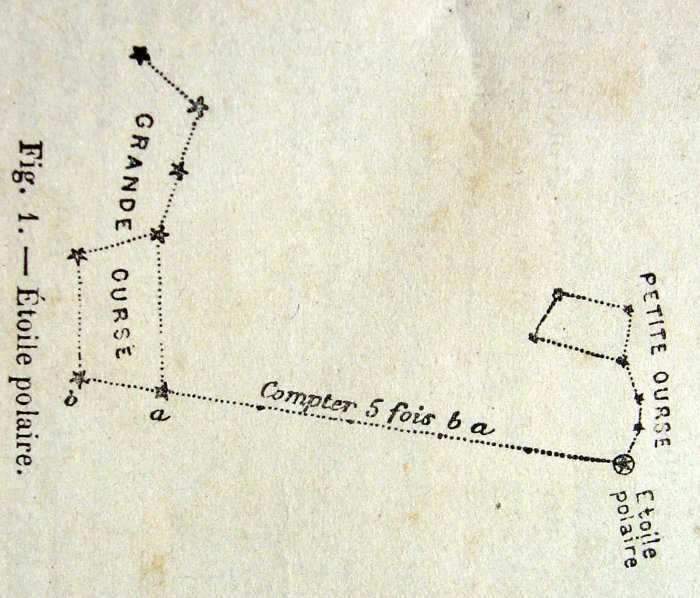

The Little Dipper, as it is commonly called, is a well-known constellation despite its small size and lack of particularly bright stars. Its proximity to the North Pole has made it significant in the field of astronomy for centuries. Ursa Minor is often depicted as a small bear with a long tail, which is said to be the result of the bear grasping onto the Earth’s pole with its end. The seven brightest stars in Ursa Minor form a bucket shape similar to the asterism in the Big Dipper constellation. Polaris, also known as the North Star, is located at the end of the handle. Finding Ursa Minor in the sky is relatively easy, with its neighboring constellations being Camelopardalis, Draco, and Cepheus. However, the Big Dipper is commonly used as a reference point. By drawing a line through the two outermost stars of the Big Dipper’s bucket and measuring five distances between them, one can locate Polaris, which serves as the starting point of the “handle” of the smaller scoop that represents Ursa Minor. Although not as bright as the Big Dipper, Ursa Minor is still visible and distinguishable from other constellations in the night sky. It can be observed year-round in the Northern Hemisphere.

The most luminous celestial bodies of the constellation are

- Polaris (α UMi). Having a stellar magnitude of 2.02 m

- Cohab (β UMi). Having a visible stellar magnitude of 2.08 m. During the time period spanning from approximately 2000 B.C. to 500 A.D., Kohab served as the brightest star in close proximity to the Earth’s North Pole and fulfilled the role of a guiding star, which is evident in its Arabic name Kohab al-Shemali (Star of the North).

- Ferkad (γ UMi). Having a stellar magnitude of 3.05 m

- Yildun (δ UMi). Having an apparent sidereal magnitude of 4.36 m

The Tale of the Little Bear Constellation

The Little Bear and the Big Bear share not only their celestial proximity, but also captivating lore and fables, a craft in which the ancient Greeks excelled.

The primary character in stories about the Bears was typically given to Callisto, the daughter of Lycaon, the king of Arcadia. As one legend goes, her beauty was so extraordinary that it caught the attention of the all-powerful Zeus. Disguised as the goddess-hunter Artemis, who had Callisto as part of her entourage, Zeus managed to get close to the maiden, resulting in the birth of her son, Arcades. Upon learning of this, Zeus’ jealous wife, Hera, promptly transformed Callisto into a bear. Time passed, and Arcades grew up to become a handsome young man. One day, while hunting a wild animal, he stumbled upon the trail of a bear. Oblivious to the truth, he intended to strike the animal with an arrow, but Zeus intervened and prevented the killing. Instead, he transformed his son into a bear and transported both of them to the heavens. This action enraged Hera, who sought help from her brother Poseidon, the god of the seas, pleading with him to deny the couple entry into his kingdom. That is why the Big and Little Bears in the middle and northern latitudes never dip below the horizon.

There is another tale related to the birth of Zeus. His father was the god Kronos, notorious for devouring his own offspring. In order to protect the baby, Kronos’ wife, the goddess Rhea, concealed Zeus in a cave, where he was nourished by two bears – Melissa and Helis – who were later transported to the heavens.

In ancient Greece, the bear was considered an uncommon and exotic creature. This may explain why the two bears in the sky have tails that are distinctly curved, which is not typical of bears. Some suggest that Zeus impetuously pulled the bears into the sky by their tails. However, the origin of their tails may be completely different: the Greeks also had an alternative name for the constellation Ursa Minor – Kinosura (from the Greek Κυνόσουρις), which means “Dog’s tail”.

The Ladles of different sizes were frequently referred to as “chariots” or the Big and Small Voz (not only in Greece, but also in Russia). In fact, with some creative imagination, one can envision carts with harnesses in the buckets of these star formations.

During autumn, when darkness falls early, one can take advantage of a clear evening to marvel at the stars. If you reside in the Northern Hemisphere, locating the Big Dipper and Polaris is quite simple. How can you educate your child about these constellations? Let us turn to ancient myths that elucidate their origins.

Legends of the night sky

The Great Bear and its offspring

The Great Bear is readily visible – it radiates a brilliant glow in the celestial sphere. However, not every individual is aware that the bear is merely a constituent of the constellation known as the Great Bear, which appears in the following manner:

Looking for constellations is an interesting activity. At first glance, the stars may not resemble a bear. However, what if we try connecting the stars with lines?

Illustrations sourced from the book How to Find the Constellations.

So that is the Bear. However, there is more to it. If you observe closely, right next to the Big Dipper, you can spot a smaller dipper positioned upside down. That is the Little Bear, also known as the constellation Little Bear.

Illustration from the book “Fascinating Astronomy”

There is a captivating legend that explains how the bear and her cub ended up in the sky.

What is the origin of bears in the sky?

Many years ago, there was a stunning woodland nymph named Callisto who was a companion to the mighty Artemis, the goddess of hunting. One fateful day, the powerful Zeus noticed Callisto in a shaded grove and instantly fell in love with her, captivated by her strength and elegance.

As a result of Zeus and Callisto’s union, a son named Arcades was born. However, it was forbidden for Artemis’ companions to fall in love, so the goddess banished Callisto. When Hera, Zeus’ jealous wife, discovered this tale, she became enraged. She vowed to seek revenge and transform Zeus’ beloved into such an ugly creature that he would no longer desire to gaze upon her.

Artwork taken from Legends of the Night Sky.

Hera managed to catch up with the nymph. Callisto extended her arms, pleading for forgiveness, but in an instant her skin transformed into a cloak of black wool. Her delicate hands and feet morphed into furry paws adorned with jagged claws, while her lovely countenance morphed into a broad visage with a horrifying snout. The nymph cried out for assistance, but all that escaped her mouth was a beastly growl.

Callisto had been wandering the forest disguised as a bear for a lengthy fifteen years. She used to be a hunter herself, but now she had to stay hidden from those who were after her. One morning, she heard the familiar sounds of hunters approaching. Callisto attempted to escape, but found herself trapped in a net between the trees. Then, she caught sight of a young man aiming a bow at her. It was her son, Arcade. She desperately called out his name as she rushed towards him, but Arcade only saw a massive, roaring bear. The young man pulled back the bowstring….

However, the gods intervened. Zeus transformed Arcade into a bear cub so that he could understand his mother’s words. Then, the king of the gods seized both of them by their tails and flung them into the sky to live peacefully as constellations – the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper.

The North Star

Engrossing celestial science

On the tip of the little bear’s tail, you can observe a luminous star. This particular star is known as Polaris. Polaris remains fixed in the sky, unlike other stars and constellations that appear to shift across the celestial sphere.

Illustrations from the book How to Find the Constellations

Polaris, also known as the North Star, earned its name because it consistently remains in the northern hemisphere. By facing Polaris, one can determine the cardinal directions: north in front, east on the right, west on the left, and south behind. This knowledge allows for navigation even without a compass, ensuring those who can locate Polaris never become lost.

The Big Dipper, a well-known constellation situated in the northern sky, stands out among the rest. It is a circumpolar constellation, meaning it can be seen year-round in the northern hemisphere. However, in the autumn months, it may dip closer to the horizon in southern regions. The shape of the Dipper’s bucket is easily recognizable and can typically be spotted by most individuals with ease.

The arrangement of stars known as the Big Dipper in the celestial sphere

This particular pattern of stars is situated in the northern region of the celestial sphere and is visible throughout the year. During the winter season, it gradually sets closer to the horizon but as time goes on, it starts to ascend higher and higher. Throughout the night, it traces a significant arc due to the Earth’s daily rotation. The optimal time to observe it is during the spring season.

The Big Dipper constellation can be observed in the night sky.

Stars in the Big Dipper constellation

The Big Dipper constellation is larger than what most people realize and is not limited to the well-known seven-star “bucket.” It is actually the third largest constellation in terms of area, following Hydra and Virgo. There are approximately 125 stars visible to the naked eye within this constellation.

The stars that form the “bucket” of the Big Dipper are the brightest in this constellation, but they only have a brightness of about two star magnitudes, except for Delta, which has a brightness of 3.3m.

Each star in the “ladle” has its own unique name – Dubhe, Merak, Fekda, Kaffa, Aliot, Mitzar, and Benetnash. Perhaps the most well-known among them is Mitzar, located in the middle of the ladle’s handle. Mitzar is an interesting star as it is actually a binary star, and those with exceptional eyesight may even be able to spot its companion, Alcor.

The celestial bodies that form the pattern known as the Big Dipper.

Merak and Dubhe have earned the nickname Pointers – by drawing a line connecting them and extending it, one will arrive at Polaris, commonly known as the North Star. The constellations of the Little Dipper and the Big Dipper are positioned in close proximity, facilitating the process of locating Polaris.

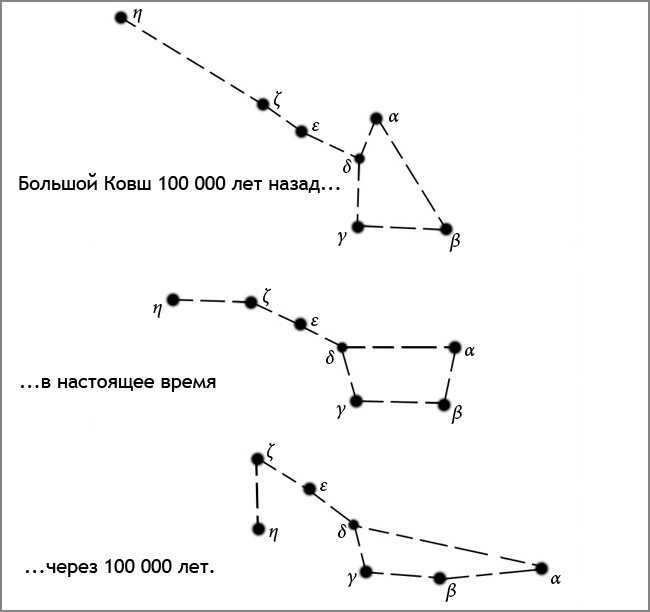

The motion of the stars in the Big Dipper within the vast expanse of space.

The Big Dipper is a collection of stars that boasts numerous pairs and even groups of stars, but the majority of them are either too faint or too near to be seen with most amateur telescopes. Additionally, there are numerous stars that vary in brightness, although these too are quite dim and would necessitate the use of a telescope or high-quality binoculars for study.

The constellation of the Big Dipper can be seen on this map.

Mizar consists of six stars

Mizar is positioned in the middle of the handle of the Big Dipper. It is interesting because it is a binary star, one of the most well-known and easily observable. The second star is called Alcor and it is a dim star with a magnitude of 4.02m, located 12 minutes away. Only individuals with exceptional eyesight can spot Alcor next to Mizar without the aid of a telescope, which is why it has historically been used as a vision test.

For a long period of time, there was no concrete proof of the physical connection between Mizar and Alcor as the distance between them in space is a quarter of a light year and the stars’ orbital movement is extremely slow. In 2009, such evidence was finally obtained, revealing that the Mizar-Alcor system is not just a binary system, but actually a sixfold system!

Mizar can be observed as a binary star even with a small telescope – the angular separation between its A and B components is 15 seconds, and the stars have a luminosity of approximately 4m. However, both of these components are also binary systems! Hence, Mizar is a quadruple star. Component A is composed of a pair of hot white stars, each 3.5 times larger and 2.5 times more massive than the Sun. The stars in component B are also white stars, but slightly smaller – twice as large and 1.6 times heavier than the Sun.

Alcor is not as straightforward as it seems either. It is a binary system comprising a hot white star twice as massive and larger than the Sun, and a red dwarf, which is four times lighter than the Sun and three times smaller.

Variable stars in the constellation Ursa Major

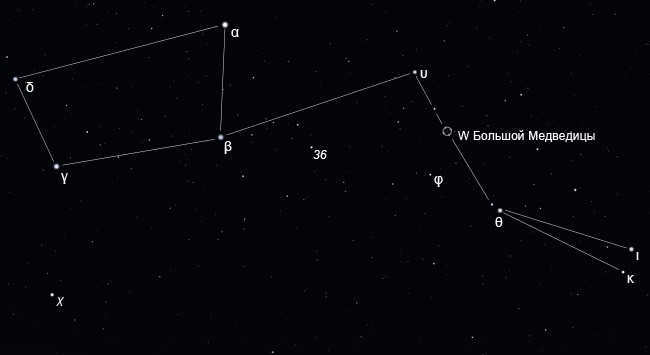

There are over 2,800 known variable stars in the Ursa Major constellation, but the majority of them can only be observed with a powerful telescope. However, there are three variable stars in the Big Dipper – W, R, and VY – that are particularly interesting and can be seen with binoculars or a telescope.

W in the Big Dipper

W is an eclipsing variable star that is similar to the famous Algol, but with more extreme characteristics. It consists of a pair of white stars, each with sizes and masses comparable to that of the Sun, that are so close to each other that they are almost touching. Due to their close proximity, both stars have become elongated and have taken on an egg-like shape under the influence of each other’s gravity. As they orbit around a common center of gravity, the stars always face each other with one convex side. In fact, they even exchange matter with each other.

The configuration of Ursa Major’s W-shaped stars is visually striking.

As the stars revolve around each other, one star in this pair periodically eclipses the other, causing the overall brightness of the system to fluctuate. Furthermore, the stars can be observed in a wide, elongated form or a narrow shape. Consequently, the brightness of Ursa Major’s W-shaped stars constantly varies between magnitudes 7.8 and 8.6. The complete cycle takes only 8 hours, illustrating the rapid pace at which these stars orbit each other. As a result, the entire cycle can be witnessed within a single night.

R in the Constellation Ursa Major

There is a variable star located in the constellation Ursa Major. It is classified as a member of the myrids class. The star’s brightness varies significantly, ranging from a maximum magnitude of 6.7, which can be observed with binoculars, to a minimum magnitude of 13.4, requiring a powerful telescope to see. The star’s light fluctuations occur over a period of approximately 300 days.

The VY star located in the constellation of the Big Dipper

When compared to other stars, VY is notably bright with a luminosity that fluctuates between 5.9 and 6.5m. This makes it easily visible even with binoculars that have a magnification of 8-10x. VY is classified as a semi-regular variable star, meaning it has a predictable period of 180 days, but it also exhibits irregular oscillations.

Even if you’re not specifically interested in observing its light changes, it is worth taking a moment to gaze at this star. VY is classified as a carbon star, which means it is a giant star with a significant amount of carbon in its atmosphere. As a result, VY has a striking red color that sets it apart from the surrounding ordinary stars.

The position of VY in the constellation of the Big Dipper can be easily identified.

Within the Big Dipper constellation, there are numerous fascinating celestial objects, particularly galaxies. Some of these galaxies can be observed with binoculars, and we will discuss them in a future article.

For a more productive exploration of the night sky, we recommend using an atlas designed for beginner stargazers.

There are numerous constellations that are distinct from each other. Some of them are widely recognized while others are only known by a select few. However, there is a group of celestial bodies that is universally understood. This article will explore the positioning of the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper. These constellations are accompanied by a plethora of captivating myths and legends, some of which will also be shared. Additionally, we will discuss the most prominent and dazzling stars that can be observed within this highly popular cluster.

The night sky has always captivated our attention

With its starry expanse, the Big Dipper, the Little Dipper, Andromeda, and the Southern Cross, the night sky is a sight of unparalleled beauty and grandeur. Countless stars twinkle and gleam, beckoning curious minds to gaze upon them. Throughout history, humanity has sought to understand its place in the vast universe, pondering the organization of the world and whether our existence is the result of divine creation or if we ourselves possess divine qualities. As we sit by the fire at night, gazing into the boundless sky, we come to realize a simple truth – the stars are not randomly scattered across the heavens. Each has its rightful place.

Each night, the stars remained unchanged, occupying the same positions. Nowadays, it is common knowledge that the stars are actually situated at various distances from the Earth. However, when gazing up into the heavens, it is impossible to discern the relative proximity of each celestial body. In the past, our ancestors could only differentiate the stars based on the intensity of their brightness. They identified a small fraction of the most radiant stars and grouped them together to form distinct patterns, which they named constellations. In present-day astrology, there exist a total of 88 constellations in the starry expanse. Our predecessors, on the other hand, were aware of no more than 50.

The constellations were referred to using various names, associating them with objects such as Libra, Southern Cross, and Triangle. Celestial bodies were named after heroes from Greek mythology like Andromeda, Perseus, and Cassiopeia, while stars were given the names of both real and imaginary animals such as Lion, Dragon, Big Dipper, and Little Dipper. In ancient times, people displayed their vivid imagination when it came to naming celestial entities. It is not surprising that these names have remained unchanged to this day.

“Turning the Earth’s axis twists a bear’s tail.”

Despite the Earth’s daily rotation on its own axis and its yearly orbit around the Sun, Polaris remains in a fixed position. The brightness of this guiding star fluctuates with a periodicity of 4 days, with an intensity range of 2.02 ± 2%. In the past, the amplitude of its luminosity was higher, but it has now stabilized. Over the last century, the total brightness of Polaris has steadily increased by almost 15%.

This pulsation is directly related to the star’s luminosity, which is characteristic of cepheids. Polaris is one of the brightest cepheids in the night sky. The constellation Ursa Minor, which includes Polaris, covers an area of approximately 255.9 square degrees in the sky. Its neighboring constellations are Draco and Cepheus.

The asterisk, as previously stated, is the location of the North Pole of the World – the point on the celestial sphere around which all objects revolve. The first reference to this was recorded by the Greek astrologer Ptolemy in the 2nd century.

Stars that make up the Bucket cluster

The arrangement of stars in the night sky known as the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper is widely recognized as one of the most famous and easily identifiable constellations in the northern hemisphere. From our early days, we learned to spot the stars of the Big Dipper, which form a dipper-shaped pattern that is instantly recognizable. This collection of celestial bodies is the third largest in size, with only the Virgo and Hydra constellations surpassing it. There are a total of 125 stars in the Big Dipper, all of which can be seen with the naked eye. The dipper shape is formed by seven of the brightest stars, each of which has its own distinct name.

Now let’s direct our attention to the Big Dipper constellation itself, as it is an integral part of our understanding of the cosmos. Within this cluster of stars, some notable ones include:

The star called Dubhe is known as the “bear” and is the brightest star in the Big Dipper. Merak, the second brightest star, translates to “loins.” Fekda means “thigh,” Megretz means “beginning of the tail,” Aliot means “curd,” and Mitzar translates as “loincloth.” Lastly, Benetnash is literally translated as “leader of the mourners.”

These are just a few examples of the stars that can be found in this well-known cluster.

Celestial bodies

The Small Bear (PGC 54074, UGC 9749) is a diminutive elliptical galaxy with a visible brightness of 11.9 and a distance of 200,000 light-years. It is a companion galaxy of the Milky Way. The majority of its stars are ancient and there is scarcely any observable star creation.

In 1954, the discovery of this galaxy took place. The Hubble Space Telescope provided information in 1999 that confirmed the galaxy’s formation period occurred 11 billion years ago and lasted for 2 billion years.

If you want to explore the constellation Ursa Minor in the northern hemisphere in more detail, you can utilize not only our photographs but also 3D models and an online telescope. To conduct your own search, a star map will be useful.

Spotting the constellations of the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper in the night sky is a relatively simple task. March and April are the optimal months for observing these celestial formations. On clear spring evenings, the Big Dipper can be easily seen directly above us. The stars that make up this constellation are positioned high in the sky. However, as we progress into the second half of April, this cluster of stars begins to shift towards the west. Throughout the summer months, the constellation gradually moves in a leisurely fashion towards the northwest. By the end of August, the Big Dipper can be observed low in the northern part of the sky. It remains in this position until winter arrives. During the winter months, the Big Dipper once again rises above the horizon, recommencing its journey from north to northeast.

Place

The constellation known as the Little Dipper can be easily located in the night sky. It is surrounded by the constellations Giraffe, Dragon, and Cepheus. However, the Big Dipper is often used as a reference point for finding it. By drawing a line through the two outer stars of the Big Dipper’s scoop and measuring five distances upwards, you will come across Polaris, also known as the North Star. Polaris serves as the starting point for the “handle” of another, smaller scoop, which represents the Little Bear constellation. Although it is not as bright as the Big Dipper, it is still visible and easily distinguishable from other constellations. In the Northern Hemisphere, the Little Dipper can be observed throughout the year.

Changes in the position of stars depending on the time of day

Let’s focus on how the positions of the Big and Little Dipper constellations change throughout the day. For instance, during the night in February, we observe the bucket with the handle pointing downward in the northeast. However, in the morning, the constellation will shift to the northwest, and the handle will be turned upward.

Interestingly, the five stars inside the bucket form a distinct group and move independently from the other two stars. Dubhe and Benetnash are gradually moving away in the opposite direction from the other five stars. Consequently, in the near future, the dipper will have a completely different appearance. However, we won’t be able to witness this change, as it will become noticeable only in approximately one hundred thousand years.

Asterism Small Bucket photo by astrophotographer Rogelio Bernal Andreo

The constellation consists of two asterisms: the Small Bucket and the Guardians of the Pole. The former is familiar to contemporary observers. The Little Bucket of the Little Bear constellation is very similar to the nearby Big Bucket, but it is not as bright. It is made up of the most prominent stars in the celestial formation. Many people believe that the Little Dipper is only composed of these seven objects, but in reality, there are 18 additional stars in its composition.

The second asterism is much less well-known and its name dates back to ancient times when the two stars comprising it, called Ferkad and Kohab, were located closer to the pole than Polaris.

The Enigma of the Celestial Twins Mizar and Alcor

Within the constellation known as the Big Dipper, a celestial pair of stars named Mizar and Alcor captivate astronomers and stargazers alike. What makes them so intriguing? In ancient times, these twin stars served as a test of visual acuity for humans. Mizar, a star of medium size, resides within the bowl of the Big Dipper, while its companion, Alcor, rests nearby, albeit with a slightly less discernible appearance. Those blessed with keen eyesight effortlessly spy this stellar duo, while those afflicted with poor vision may perceive them as a single, radiant speck in the night sky. However, beneath their shining exterior, these two stars harbor a couple of additional enigmatic secrets.

The human eye is unable to detect the unique characteristics present in them. When a telescope is directed towards Mizar, it reveals the presence of two stars instead of just one. These stars are known as Mizar A and Mizar B. However, there is more to it. Analysis of their spectra has discovered that Mizar A is composed of two stars, while Mizar B consists of three. It is unfortunate that these celestial bodies are located at such a great distance from Earth that no optical instruments can fully uncover their secrets.

How to Locate a Constellation in the Night Sky

If you want to find a specific constellation in the sky, there are a few things you need to know. First, the visibility of a constellation depends on your latitude. In general, you can see the constellation from latitudes ranging from -10° to +90°. This means that no matter where you are in the world, you should be able to spot it at some point throughout the year.

It’s important to note that the best conditions for observing a constellation are usually in late summer, fall, and winter. During these seasons, the sky is clearer and there is less light pollution, making it easier to see the stars. In Russia, the constellation is visible year-round and can be easily spotted.

When it comes to finding the Little Dipper, things can get a bit trickier. This constellation is well-known, but it’s not as easy to locate as some others. The main challenge is that only the two outermost stars of the dipper are bright enough to be seen with the naked eye. However, there is a helpful trick you can use to find it.

The key is to look for Polaris, also known as the North Star. Polaris can be found by using the Big Dipper as a guide. In the fall, the Big Dipper is located to the right and below the Little Dipper. By following the line formed by the two outermost stars of the Big Dipper, you can easily locate Polaris, which will then lead you to the Little Dipper.

So, if you’re interested in stargazing and want to find a specific constellation, keep these tips in mind. With a bit of practice and patience, you’ll be able to navigate the night sky like a pro.

During the winter season, the constellation of Ursa Minor appears tilted, causing its dipper to point downwards towards the northeastern part of the horizon. Meanwhile, the Big Dipper can be seen situated to the right and slightly higher. Additionally, Cassiopeia, positioned above the Big Dipper, becomes prominently visible to the left of Ursa Minor.

During the summer’s midnight, the constellation of the Little Dipper assumes a position above its elder sibling. The inseparable duo can be easily observed on the right side: Cassiopeia above, and Perseus slightly below. On the left side, at a significant distance, are the Ursa Minor and the Corona Borealis.

Stellar members of the Ursa Minor constellation.

The two stars located on the wall of the dipper are commonly known as the Pointers. These stars, Merak and Dubhe, earned this name because when a straight line is drawn through them, it leads to the polar star in the constellation of the Little Bear. This group of stars is also referred to as near-polar. The constellation of the Little Bear consists of a total of 25 stars, all of which can be observed with the naked eye. Among these stars, there are some that are particularly well-known and stand out as the brightest.

One of the notable stars in this cluster is Cohab. From 3000 B.C. to 600 A.D., this luminary served as a crucial reference point for mariners, as it is part of the constellation of the Little Bear. Polaris, another famous star in this group, indicates the direction towards the North Pole. Fercadus and Yildun are also among the well-known luminaries of this constellation.

Meteor streams in Ursa Minor

The constellation Ursa Minor is home to a particular meteor shower known as the Ursids. This celestial event starts on December 17 and typically lasts for approximately one week. The peak of activity occurs on December 22, during which observers can expect to see around 10 meteors per hour. However, there have been instances where the Ursids have exhibited a significant increase in activity, such as in 1945 when the hourly meteor count reached an impressive 120.

The Ursids meteor shower occurs as a result of the comet Tuttle, which was initially observed by Pierre Mechene in 1790. This particular comet completes a full orbit around the sun in approximately 14 years.

The constellation known as the Little Bear is constantly visible in the night sky. Although it may not have many notable features, taking the time to locate it and observe its stars can still be a worthwhile experience. Don’t forget to point out Polaris to your children!

There was a lack of a common name for a significant period of time

The constellation known as the Little Bear has a similar shape to that of a dipper, much like the Big Dipper. The Phoenicians, renowned ancient navigators, used this group of stars for navigation purposes. However, Greek sailors were more inclined to rely on the Big Dipper for their navigation. The Arabs, on the other hand, saw a rider in the Little Dipper – a red-skinned monkey that clings to the center of the world with its tail and revolves around it. For a long time, there was no universally accepted meaning or name for this constellation, and each nation saw something of its own significance in the starry sky, something that was familiar and easily explainable. What more can the Big Dipper constellation reveal about itself?

Photo Galaxy dwarf of the Little Bear

Aside from the primary stars, there is a fascination with the galaxies situated in Ursa Minor. The aforementioned Dwarf, serving as a companion to the Milky Way, was first observed in 1954. This ancient galaxy is believed to be at least ten billion years old. Due to its diminutive size, it is difficult to ascertain whether it possesses any gas, dust, or ongoing star formation activity. Occasionally referred to as Polarissima due to its proximity to the Earth’s rotational axis.

Moreover, within the constellation lies the galaxies NGC 6217 and NGC 5832. All of these celestial objects mentioned are relatively minuscule in the grand scheme of the universe, making them virtually imperceptible without the aid of advanced optical instruments.

Legends surrounding the constellation. The star Dubhe

There are numerous legends and stories surrounding the collection of celestial bodies known as the Big Dipper and Little Dipper.

One particular belief centers around the brightest star in the Big Dipper constellation, Dubhe. According to the tale, Callisto, the beautiful daughter of King Lycaon, was one of the huntresses of the goddess Artemis. Zeus, the all-powerful deity, fell in love with Callisto and she gave birth to a son named Arkas. In a fit of jealousy, Zeus’ wife Hera transformed Callisto into a bear. As Arkas grew older and became a hunter, he stumbled upon a bear and prepared to shoot it with an arrow. However, Zeus intervened and prevented the killing, instead transforming Arkas into a smaller bear. To ensure that the mother and son would always remain together, Zeus placed them in the night sky as constellations.

Galaxies in the Ursa Minor Constellation

The Ursa Minor constellation offers limited opportunities for amateur stargazers to observe galaxies. There is only one galaxy present in this constellation, and it is a dwarf elliptical galaxy, commonly referred to as the Little Bear.

The galaxy known as the Little Dipper is a fascinating celestial wonder. It is composed of a collection of ancient stars, which formed approximately 14 billion years ago and continued to evolve for a span of 2 billion years. Over time, the rate of star formation within this galaxy has significantly decreased, resulting in the emergence of new stars being a rare occurrence.

Similar to the Magellanic Clouds, the Little Dipper Galaxy is a satellite of our very own Milky Way. These interconnected galaxies offer a captivating glimpse into the vastness and intricacies of our universe.

Feeling hopeless, Eriulok made his way to the Arctic Ocean and called upon the goddess Arnarkuachssak, who ruled over the depths of the sea. He shared his story of failure with her. The goddess offered her assistance, but on the condition that Eriulok retrieve a ladle filled with magical berries that had the power to restore her youth. Eriulok agreed to the task and journeyed to a distant island, where he discovered a cave guarded by a bear. After a lengthy struggle, he managed to lull the forest creature to sleep and pilfer the ladle filled with berries. True to her word, the goddess rewarded the hunter with a spouse, while she indulged in the marvelous berries. Eriulok went on to marry and start a large family, causing much envy among his neighbors. As for the goddess, she consumed all the berries, regaining centuries of youthfulness. Overjoyed, she flung the empty ladle into the sky, where it caught onto something and remained suspended.

The Polaris system

It should be noted that before us lies an entire star system, which possesses specific features and classification. The primary star within this system is the yellow supergiant (F7) Alpha of the Little Bear Aa. It outshines the Sun by a factor of 2500, weighs 4.5 times more, and boasts a radius 46 times larger. This star falls under the category of variable cepheids, displaying pulsations over a span of four days.

Polaris A is a classical I Cepheid variable star, and it is the most luminous example in the entire sky. These types of stars are utilized by scientists to determine distances between galaxies and clusters. Polaris A’s brightness fluctuates by 0.03 magnitudes over a period of 3.97 days. The variability of its brightness was first discussed in 1852, but it was not confirmed until 1911.

From 1963 until 1966, the star’s amplitude reached 0.1 magnitude and gradually decreased. However, since 1966, the magnitude has approached 0.05. Currently, astronomers have observed a steady increase of 3.2 seconds per year.

Alpha Minor Aa, the star, is accompanied by two other celestial bodies. The first one is Ab, a dwarf star (F7), which is located at a distance of 17 astronomical units and has an orbital period of 29.6 years. The second companion is Alpha Minor B, another dwarf star (F3), which is positioned 18 arc seconds away and has an orbital period of 42,000 years. This particular star was first discovered by astronomer William Herschel in the year 1780.

In addition to these two companions, Alpha Minor Aa also has two more satellites named C and D. The north celestial pole can be found between the stars Polaris and Lambda of the Little Bear constellation.

In 1929, the binarity of Polaris A was confirmed. It was not until 2006, with the help of the Hubble Space Telescope, that all three stellar components were finally detected. Over the course of observation by Greek astronomers, the brightness of the star has increased by 2.5 times.

A heartwarming tale of righteousness and wickedness

Legend

There are two distinct tales surrounding the Small Bear. The initial account revolves around Ida, a nymph who nurtured Zeus during his infancy on the isle of Crete. Rhea, his natural mother, was compelled to conceal him from Cronus, his father, who sought to slay all his offspring due to a prophecy. Upon Zeus’ birth, she substituted a stone in his stead and deceived her spouse. In the end, the prophecy was fulfilled as the son dethroned his father and liberated his siblings, who subsequently ascended to become the divine beings of Mount Olympus.

According to another ancient legend, the 7 stars actually symbolize the Hesperides, who were the daughters of Atlas and were responsible for protecting the apples in Hera’s garden.

The group of stars known as Polaris, Yildun, Epsilon, Eta, Zeta, Gamma, and Beta form the constellation known as the Small Bucket.

Polaris’ trinary star system.

The disappearance of the aura of enigma due to progress

Throughout history, constellations have served as guides for navigation in space, both in ancient and modern times. Explorers and seafarers have relied on the brightness and position of constellations to determine time, find their way, and more. However, with the advent of technology, our connection to the mysterious, star-filled sky has waned. We no longer gather around fires as often, nor do we gaze up at the night sky with the same sense of wonder. The legends and stories surrounding constellations like the Big and Little Dippers, Cassiopeia, and Canis Major have faded from our collective memory. Nowadays, few people can accurately point out the Big and Little Dipper constellations. Our knowledge of astronomy tells us that stars are distant celestial bodies, many of which are similar to our own Sun.

The invention and advancement of optical telescopes have resulted in numerous discoveries that were previously incomprehensible to our ancestors. It is remarkable that humans have even been able to venture to the Moon, collect samples of lunar soil, and safely return. Science has dispelled the veil of obscurity and enigma that shrouded the celestial bodies for centuries. Yet, we still gaze surreptitiously at the heavens, searching for constellations such as the snow-white Bear, the majestic Leo, or the creeping Cancer. This is why many individuals enjoy marveling at the cloudless night sky, where a multitude of luminaries, their combinations, and clusters can be clearly observed.

Observing spring constellations

During the spring season, it is quite convenient to engage in the activity of observing the constellations called Volopassus, the Northern Crown, and Leo. In the constellation of Volopassus, there exists a rather prominent reddish-yellow star known as Arcturus. To locate this star, one can simply extend the line that connects the last two stars of the “bucket handle” of the Big Dipper in a backward direction.

Adjacent to Volopas, there is a cluster of faint stars that form a wreath-like shape. This particular cluster is known as the Northern Crown constellation.

Beneath the Big Dipper, one will find the expansive zodiacal constellation of Leo. The arrangement of its primary stars closely resembles a sickle with a handle, and at the end of this sickle is a brilliant star known as Regulus, which is commonly referred to as the “Heart of the Lion”.

The Big Dipper is likely the first constellation that we all become familiar with when we start to learn about the stars (although, unfortunately, many people’s knowledge ends there.) Let’s begin with this remarkable constellation. Interestingly, it is one of the largest constellations in the sky and the familiar “dipper” shape is just a small part of it. Why did the ancient Greeks associate this particular group of stars with a bear? According to their beliefs, the vast Arctic region was located to the north and was inhabited solely by bears. (In Greek, “arktos” means bear, hence “arctica” – the land of bears.) So, it’s no wonder that bear imagery adorns the northern portion of the night sky.

The drawing of the Polyphemus story found in Switzerland may still contain the original version: the monster, a dwarf with a single eye discovered by a hunter, reigns over the creatures of the mountain. However, this version of the tale likely vanished as the glaciers advanced during the Last Glacial Maximum, which reached its peak around 500 years ago. Subsequently, a new version emerged, depicting the monster residing in a shelter. This revised rendition appears to have been disseminated through successive migrations in the Caucasus and Mediterranean regions, as well as the protection of humans and other species during periods of significant climate change.

According to one of the ancient Greek legends, the constellations are described as follows:

In a bygone era, King Lycaon ruled over Arcadia, and he had a daughter named Callisto, who possessed exceptional beauty that even Zeus himself admired.

In secret from his envious wife, the goddess Hera, Zeus would often meet with his beloved, and soon Callisto gave birth to a son named Arkadus. The young boy grew up swiftly and soon became a skilled hunter.

Phylogenetic tree connections reveal that the Homeric renditions of Polyphemus spawned an oral tradition that spread independently among various groups, including the ancestors of contemporary populations in Hungary and Lithuania. Delving into the ancestral proto-myth, the phylogenetic reconstructions of both Polyphemus and the Space Hunter stories have been established through decades of research conducted by scholars, who primarily relied on oral and written versions of tales and legends.

In the legend of Polyphemus, the original story, it is believed that a hunter encountered one or more monstrous creatures who controlled a group of untamed animals. The hunter finds himself in a location where a creature is protecting its animals and manages to find a way to escape by hiding behind a massive obstacle. The hero successfully flees by clinging to the underside of one of the animals.

However, Hera discovers that Zeus and Callisto are in love. Out of anger, she transforms Callisto into a bear. When Arcadus returns home after a hunting expedition, he sees a female bear. Unaware that it is his own mother, he prepares to shoot his bow. But Zeus, being all-knowing and all-powerful, seizes the bear by its tail and carries her up into the sky, where he transforms her into the constellation known as the Big Dipper. As he carries her, the bear’s tail elongates.

What is the number of stars in the Big Dipper constellation?

According to various phylogenetic databases and statistical and ethnological data, it is believed that ancient cultures widely believed in the existence of a powerful animal master who held them captive and needed to be appeased for their freedom. This belief may have influenced the concept of the underworld in the Paleolithic era. In the midst of a buffalo herd, another animal resembling a tooth turns its head towards the human hybrid, and there is a connection between the two beings.

In addition to Callisto, Zeus also brought her favorite handmaiden to the sky, transforming her into the constellation of the Little Bear. Arcadus, too, was immortalized in the sky as the constellation Volopas.

In the vicinity of the Big Dipper and Volopassus constellations, there lies the constellation of Canine Companions, discovered and named by Jan Hevelius. This constellation seamlessly integrates into the ancient Greek mythology, as it represents the hunter Volopassus who keeps the Canine Companions under his control, ready to attack the enormous Big Dipper.

Ursa Major

The Ursa Major constellation is well-known not only for its role in helping locate Polaris in the night sky, but also for its abundance of captivating celestial objects that can be easily observed using basic amateur equipment.

Take a look at the middle star located in the “handle” of the Big Dipper – ζ. It is one of the most well-known binary stars – Mizar and Alcor (these names have Arabic origins, similar to most star names, and they mean Horse and Rider). These stars are positioned quite far apart in space (these types of pairs are referred to as optical binaries), but the brighter star Mizar also appears as a binary when observed through a telescope. In this case, the stars are truly connected by gravitational forces (a physical binary) and orbit around a shared center of mass. The brighter star has a luminosity of 2.4 m, and 14″ away from it is a companion star with a magnitude of 4 m. However, that’s not all – each of these stars is also a binary, but these pairs are so close together that they cannot be distinguished by even the largest telescopes, and only spectral observations can detect their duality (these stars are known as spectroscopic binaries). Therefore, Mizar is a quadruple star (excluding Alcor). In one location, we can observe examples of all types of binary stars simultaneously.

This interpretation of the Cosmic Hunt narrative might provide an explanation for the renowned Paleolithic “beautiful scene” discovered in a cave in Lascaux, France. It would make sense for an animal that doesn’t convey the impression of actual movement to represent a constellation rather than an action.

Furthermore, according to certain experts, the figure of the man could be standing upright while the bison might be ascending, mirroring the celestial animals in the proto-mythical sky. Establishing a connection between the mythic tale and the Paleolithic depiction is challenging. These instances merely demonstrate the interpretive capability of the phylogenetic approach in proposing plausible hypotheses and reconstructing narratives that have long been lost.

The Big Dipper constellation. (hover over an object to view its photograph)

Recent research provides support for the theory that the origins of anatomically modern humans can be traced back to Africa and that they subsequently migrated to other parts of the world. This aligns with the findings of biologists who have conducted phylogenetic studies indicating that the initial major wave of human migration originated in Africa and followed the South Asian coastline, resulting in the inhabitation of Australia approximately 50,000 years ago and the eventual migration to the Americas from an East Asian origin. Both biological and mythological perspectives suggest that a second migration occurred, with North America being reached around the same time as the influence from Eurasia in the north.

And in the southern part of the Mediterranean, we can observe a distinct duo – the galaxies M81 and M82. They can be seen through small telescopes, but to truly appreciate their unique features, one needs a lens diameter of at least 150mm. M81 is a typical spiral galaxy, while its neighboring galaxy M82 is a stunning example of an irregular galaxy. In images, it appears as if it has been ravaged by a massive explosion. However, these intricate details are not visible to the naked eye, although the dark patch in the galaxy’s center can be observed with relative ease.

A recent construction of a phylogenetic supertree explores the progression of serpent and dragon legends that emerged during these initial waves of migration. One ancient story, believed to precede the exodus from Africa, incorporates the following fundamental components: mythical serpents guard water sources, only releasing liquid under specific circumstances. These serpents are colossal in size and possess horns or antlers on their heads. They have the ability to generate rain and thunderstorms. Within this context, an individual in dire straits starts to be perceived as a serpent or other small creature that brings life or healing to itself and other animals.

In the same telescope field of view, two additional nebulae can be observed slightly south of the “bottom of the bucket,” near β of the Big Dipper. These are the galaxy M108 and the planetary nebula M97, also known as the “Owl.”

The Small Bear

Maybe the solitary point of reference in this diminutive constellation is Polaris. At present, it is situated in close proximity to the celestial pole – at a distance of slightly over 40" (although, everything is relative, this distance is significantly larger than the visible diameter of the Moon). The position of Polaris is not permanent – the Celestial Pole shifts in the sky (this phenomenon is known as precession) and in approximately a century, the pole will start to gradually move away from it. (for more information about precession, you can refer to the link)

Names of the stars in the Big Dipper

- Observing the star should not pose much of a challenge.

- Alcor can be found by driving 12 minutes to the east.

Exploring the constellations of Ursa Minor and Draco. (hover over an object to view a photo)

Dragon

The Dragon constellation is characterized by a prominent series of stars encircling the Little Dipper. In ancient Greek mythology, it is believed that the Dragon was a fearsome creature slain by Hercules while protecting the entrance to the Garden of Hesperides.

Stars that belong to the Bucket cluster

NGC6543, also known as the Cat’s Eye planetary nebula, is a prominent feature in the constellation. Situated 3000 light years away from the Sun, this nebula is positioned towards the ecliptic pole. Despite its relatively small size, it can be easily observed through medium telescopes. However, the true beauty of the nebula, which earned it its name, can only be fully appreciated in photographs.

Referred to as a subcarrier, the star possesses a diameter that is half the size of the Sun and a luminosity that is only a fifth of the Sun’s. However, despite its smaller size, it is located in such close proximity that its visual magnitude is rapidly increasing. If you were to move this line to a position halfway around and observe it from a similar distance, you would notice its brightness. In this particular region, there are numerous stars with significant magnitudes, but only one star can be found to the north of the radiant galaxy. Locating this specific star can be quite an exciting adventure. It goes by the name 46 Leonis Minoris, and it is the smallest star in the Ursa Major constellation. Interestingly, there is another star nearby known as 47 Leonis Minoris.

Proceed one step in a northerly direction and then advance three quarters further. This particular section of the universe is rather devoid of matter. Two degrees to the left of that location would place you within your designated area. It possesses an orbital period of 86 days, approximately three times longer than that of Jupiter, and its orbital radius is roughly twice the distance of Earth’s. Additionally, based on the information that has been disseminated, it is likely to have a region within its atmosphere where the temperature is conducive to the liquefaction of water. Over there, you will discover a grouping of three luminous stars arranged in the shape of a crescent moon. Positioned precisely in the center of this triangular formation, proceed eastward where you will encounter the aforementioned trio of stars.

Polaris and the tiny bear

The well-known celestial body that indicates the northern direction can be easily observed in the heavens. However, it is important to note that it is not the most luminous star in the night sky! Locating it is a simple task: one must utilize the constellation Ursa Major, by extending a line from the edge of the pan five times upwards. This will lead you to a relatively isolated star, which happens to be the sole prominent star in its vicinity.

Having difficulty in identifying the Big Dipper? Polaris, also known as the North Star, is located at the end of the tail of Ursa Minor, which has a similar shape to Ursa Major but is smaller in size. The stars in Ursa Minor are relatively dim, making it challenging to spot. It remains visible throughout the year, but in areas with excessive light pollution, it may not be visible. The notable stars in Ursa Minor are Polaris and two stars situated at the opposite end of the constellation.

Legend and History

Thales of Miletus, an ancient Greek philosopher and mathematician, is credited with inventing and adding the constellation of the Little Bear to Claudius Ptolemy’s Almagest catalog of the starry sky.

There exist numerous legends surrounding the Little Bear. One such legend is tied to the birth of Zeus. According to the story, the goddess Rhea brought her newborn son to the summit of Mount Ida and entrusted him to the care of the nymphs, known as Kinosura, and their mother Melissa. Rhea took this action while fleeing from her father Kronos, who had been devouring his own offspring. As Zeus grew older, he transformed Melissa into the Big Dipper and Kinosura into the Little Dipper. Incidentally, on ancient maps, Polaris was referred to as Kinosura, meaning “tail of the dog.”

The Little Bear is a representation of Arkasa, who is the daughter of Callisto in Greek mythology. According to the myth, both of them transformed into bears and gave birth to the constellations that we are familiar with today.

If you have already located the Little Bear within the Big Bear, it becomes quite simple to find the position of the Dragon. The Dragon is a constellation that is elongated and its tail starts between the Great Bear and the Little Bear. It winds around the North Star.

However, it is important to note that although this constellation can be seen throughout the year, its stars are not very bright. Additionally, while its position may be easy to find, actually spotting the constellation can be challenging. The Dragon represents Ladon, the guardian of the Hesperides garden. One of Hercules’ twelve labors was to retrieve the apples from this famous garden. The constellation of Hercules is also located near the Dragon, which you can learn more about in the following article.

According to Aratus, in ancient times, the constellation was known as the “Little Chariot” (while the Big Dipper was referred to as the “Big Chariot”).

The Arabs interpreted the Small Bear as horsemen, while the Persians saw it as seven fruits of a date palm.

The Romans depicted it in the form of the Spartan dog.

The Indians associated this part of the sky with a monkey.

Ancient Babylonians saw a leopard, and so on. Each culture and civilization attempted to interpret and identify something within its sphere of influence.