You may be acquainted with the compact, yet arguably the most well-known compilation of celestial entities. Were you aware that the Messier Catalog was initially conceived as a form of “comet filter”? Charles Messier, the creator of the catalog, began organizing objects that resembled comets in order to avoid mistaking them for actual comets.

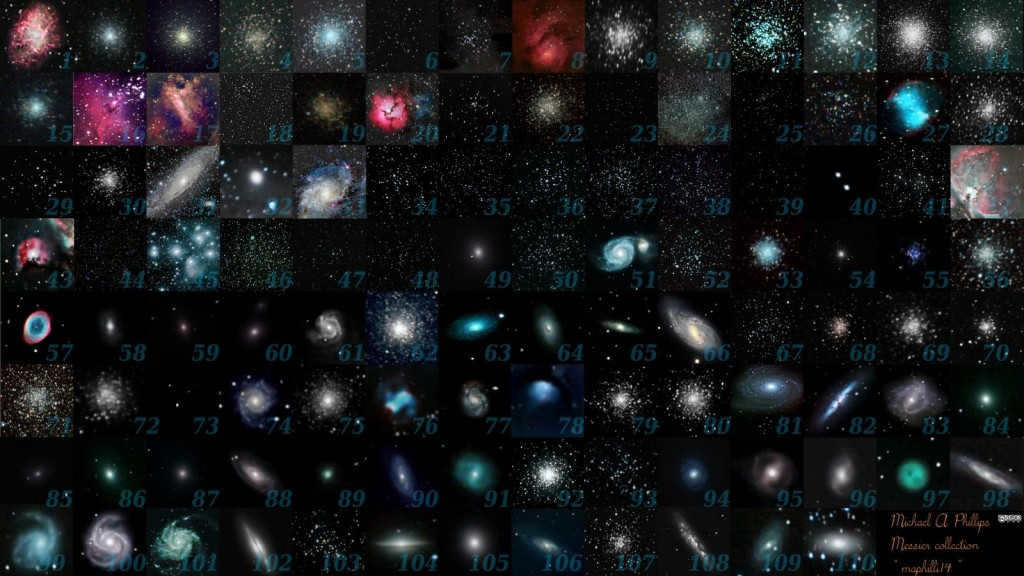

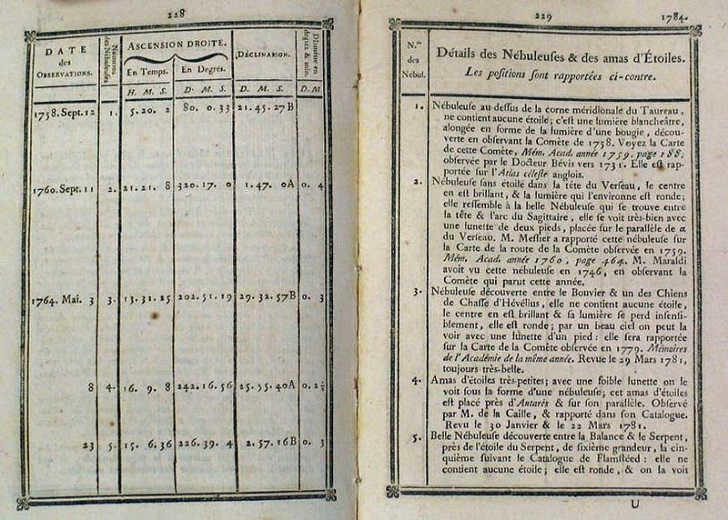

The table provided below presents the specific information pertaining to each item found within Messier’s catalog:

An exceptional aspect of this catalog is its inclusion of the most suitable objects for novice stargazers amidst the “fixed” elements of the northern hemisphere. These particular objects can be easily observed using a small telescope or even a pair of binoculars. The items within the M-catalog lack any sort of classification. Alongside an assortment of nebulae, star clusters, and galaxies, it also contains optically double stars and even a distinct “window” within the Milky Way. The sole commonality among all these objects is their undeniable visibility from Earth. This unique feature of the Messier catalog has developed over time.

Comet filter

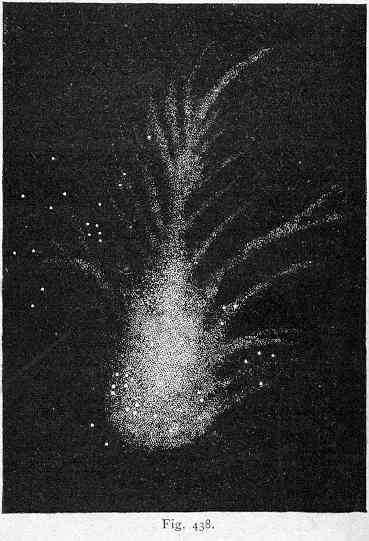

Even to this day, comets continue to be enigmatic and capricious heralds from the outer reaches of our solar system. There are currently around 400 known comets that have been studied by modern science. Some of these comets have even been visited by spacecraft, which have collected samples of their substance and even landed on their surfaces. However, despite these advancements, much about their essence remains shrouded in mystery. The number of comets that have been discovered so far is merely a drop in the bucket when compared to the estimated number of comets residing in the vast and distant Oort cloud.

At present, the configuration of this incredibly extensive area of the Solar System remains a matter of speculation. It is believed to house an astronomical number of comets, potentially in the trillions. Occasionally, a fraction of these comets venture close to the Sun, entering our observational range. The arrival of these comets is still unpredictable, even in modern times. Consequently, comets continue to be subjects of scientific discourse and even superstition. This was particularly true in the late 18th century, when the renowned “comet hunter” Charles Messier was diligently assembling his catalog.

Working on the catalog

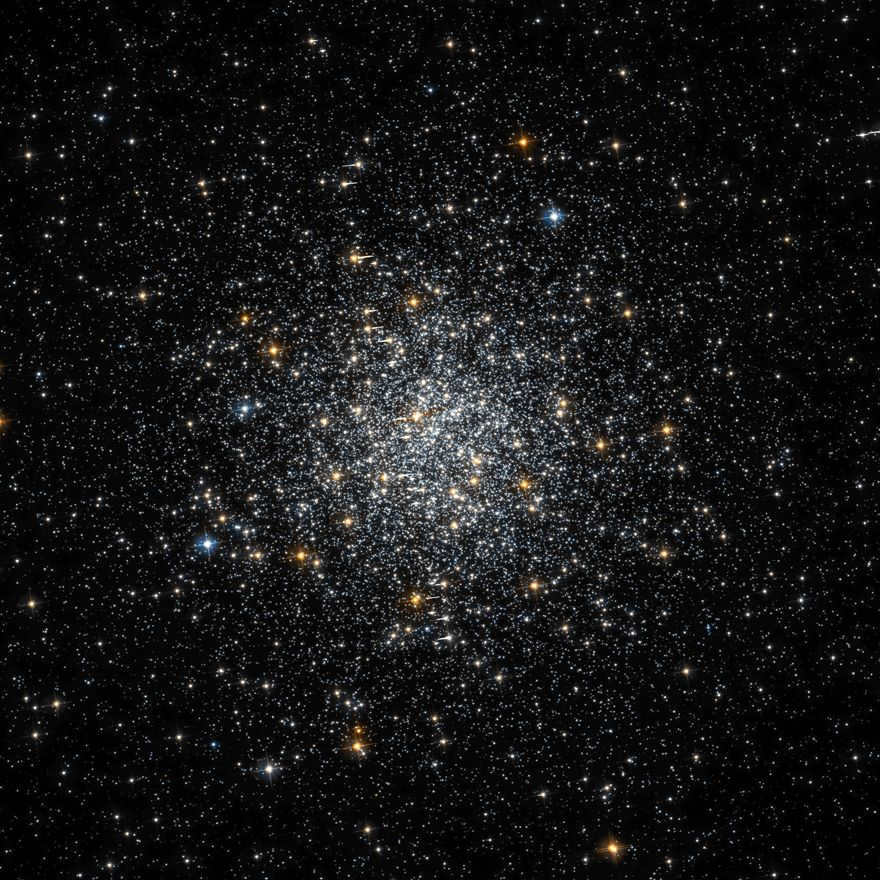

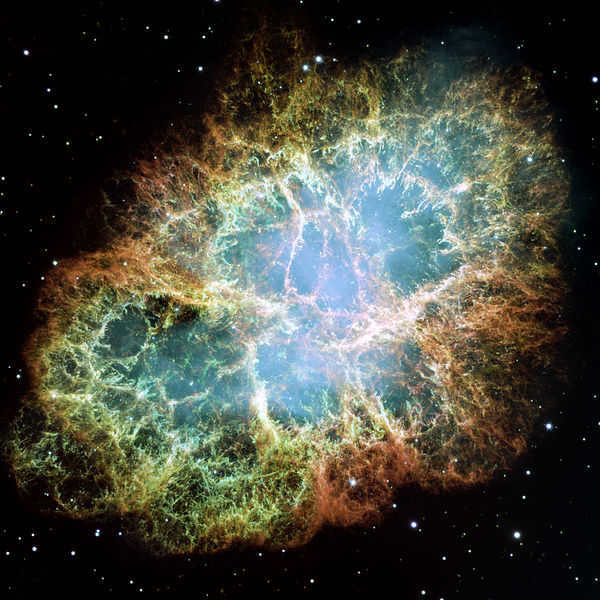

The initial entry in Messier’s catalog was a remnant of a supernova, famously known as the Crab Nebula in the Taurus constellation. Upon the discovery of this celestial object in 1758, Messier initially misidentified it as a comet and even assigned it a specific name. Unbeknownst to him, this stationary nebula had actually been observed by others as early as 1731. It was only when Messier realized that the object remained fixed in relation to the surrounding stars that he decided to include it in the inaugural edition of his forthcoming catalog. The purpose of this catalog was to encompass all those objects that could potentially be mistaken for comets by other astronomers. Following the Crab Nebula, Messier’s second entry on the list was a globular star cluster.

In 1764, Messier embarked on the task of creating a catalog. He thoroughly examined the works of astronomers from the 17th and 18th centuries, meticulously documenting the positions of potential celestial objects. To ensure accuracy, he cross-checked this information with his own observations, dedicating six months to expanding his catalog to include 40 objects. Remarkably, nearly half of these objects had never been previously observed. In the subsequent years, Messier turned his attention back to hunting for comets, temporarily setting aside the catalog. However, he couldn’t resist adding a few more objects, such as the famous Pleiades and the Orion Nebula, likely with the intention of further enriching his catalog. Eventually, he published the first version of his catalog, now featuring 45 objects.

Following the initial release of the brochure in 1771, Messier embarked on the task of documenting all the nebular entities that were visible through his telescope, not solely those resembling comets. From 1771 to 1779, he made discoveries and re-discoveries of new entities, with varying degrees of success, for inclusion in his compilation. By the time the second edition was published in 1780, approximately 70 objects were already listed. Messier’s subsequent contributions to the catalog were made in collaboration with Pierre Méchain, who was responsible for discovering the majority of the objects. Messier’s role primarily involved verifying the findings and incorporating them into the catalog. The third edition, published in 1781, featured over one hundred objects.

Completion of the catalog

In the 1780s, the renowned astronomer William Herschel also dedicated himself to the exploration of nebulous entities. His efforts were significantly more fruitful than those of Messier. The telescopes he constructed were arguably the most advanced of their time. Over the course of two decades, he identified over 2500 entities. This body of work would later serve as the foundation for the NGC catalog, which would be published by the close of the 19th century. Messier acknowledged that his objective was to compile a list of entities observable through telescopes, particularly those that were optimal for comet hunting. Herschel’s instruments were not particularly well-suited for this purpose. Thus, while Messier’s catalog contained a much smaller number of entities, they were the ones that aligned with his original objectives.

Messier had a desire to complete his catalog and reorganize the objects using a more convenient numbering system. However, despite his discovery of several more objects, he did not continue working on the catalog. This lack of progress can most likely be attributed to an accident he experienced in 1781 when he fell from a height of eight meters. It took him a considerable amount of time to recover from this incident. Additionally, Messier’s astronomical work was further complicated by the French Revolution. As a result, the creator of the catalog abandoned his creation indefinitely.

In the 20th century, additions were made to Messier’s catalog. These additions included objects that were discovered by Messier but were never included in the original catalog. As a result, the modern M-catalog now contains 110 objects instead of the 103 that were present in the last edition published during Messier’s lifetime.

Catalog items

The Messier catalog includes a total of 40 galaxies, comprising 10 nebulae (6 galactic and 4 planetary) and 57 star clusters (28 diffuse and 29 globular). Among these objects, the Pleiades stand out as the brightest and can be easily identified with the naked eye, while the dimmest have a star magnitude exceeding 10. These objects do not follow any particular order or arrangement. The galaxies in the catalog belong to various groups and exhibit a range of sizes and distances from our location. The same diversity can be observed among the objects in the other categories.

There are three additional items that do not fit into any of these groups. M40 consists of a regular pair of stars that can be observed optically, while M24 is a “vacuum”. It is well known that the light emitted by distant stars within our galaxy is obstructed by the gaseous and dusty layer of the Milky Way. M24 represents a small portion of this layer that allows us to observe the distant stars. Neither of these objects is included in the NGC catalog. The third item is a star cluster, which is likely just an optical illusion rather than a physically connected entity.

Despite its diversity of objects and absence of any organization, the Messier catalog continues to serve as the primary catalog for amateur astronomers. Nearly all of its objects are visible even when using binoculars in optimal conditions. In certain latitudes of the northern hemisphere, it is possible to see all of the catalog’s objects in a single night twice a year. Some astronomers have even accomplished a “Messier Marathon” by manually observing and recording all 110 objects in the catalog in just one night. The Messier catalog is likely to remain the go-to resource for novice observers for the foreseeable future.

Discover the extensive collection of celestial objects in the famous Charles Messier’s catalog. This catalog consists of 110 fascinating celestial bodies, and it offers a wealth of information, including search history, Messier marathon, a comprehensive list of objects, detailed descriptions accompanied by captivating photos, and valuable tips on how to locate them in the night sky. Additionally, you can also find a helpful star map to assist you in your astronomical adventures.

The Messier catalog is an invaluable resource for anyone passionate about astronomy. It serves as a practical reference guide, providing concise information about 110 significant space objects. This catalog gained prominence during the mid-18th century when the sighting of Halley’s Comet provided substantial evidence supporting Newton’s theory of gravitation. This celestial event sparked a renewed interest in space exploration, and the Messier catalog became an indispensable tool for astronomers worldwide.

It was in the year 1744 when an extraordinary event took place. Comet Chéseau (C/1743 X1), which was discovered in the latter part of 1743, gradually grew brighter as it made its way towards the Sun. By late February 1744, the comet reached its peak brightness, shining with an apparent magnitude of -7. This made it the most luminous object in the sky, second only to the Moon and the Sun. The comet’s remarkable luminosity captured the attention of numerous astronomers, one of whom was the young Charles Messier.

Charles Messier, born in 1730 in Badonvillers, France, had a rather unfortunate childhood. At the tender age of 11, he lost his father, which forced him to abandon his education. However, a few years later, he had a life-changing encounter with the comet Chéseau. This awe-inspiring sighting ignited a deep passion within him for the field of astronomy, setting him on the path to becoming one of the most renowned astronomers of his time.

When Messier was 21 years old, he worked as a draftsman in the French Navy. During this time, he gained valuable experience using astronomical instruments and developed a strong focus on his observations. These efforts eventually led to Messier being appointed as the chief astronomer of the Naval Observatory of Paris. While he was interested in various celestial objects, Messier had a particular fascination with comets, which earned him the nickname “comet sleuth” from King Louis XV.

In 1758, Messier was conducting his usual observations of a comet when he noticed a hazy object in the constellation of Taurus. After conducting a thorough survey, he determined that this celestial body was not a comet, as it did not exhibit any movement across the sky. In order to prevent other astronomers from being distracted and potentially making mistakes, Messier decided to create a catalog where he could document and classify all these “objects to be ignored.”

Charles Messier (1730-1817) was a French astronomer and author of the Catalog of Nebulae and Star Clusters. In his pursuit of comets, Messier meticulously documented a list of deep space objects to prevent others from making mistakes in their own searches.

Messier embarked on his catalog-making journey after stumbling upon NGC 1952, now famously known as M1 or the Crab Nebula. When Messier passed away in 1817, his catalog comprised of 103 objects, which encompassed his own discoveries as well as those made by fellow astronomers. In the 20th century, the list underwent a revision and expansion, resulting in a total of 110 objects.

The Messier catalog showcases a fascinating array of astronomical phenomena that can be observed from the Earth’s northern hemisphere. Some of these objects require a powerful telescope to fully appreciate, while others are bright enough to be seen with just binoculars. The relative ease of locating Messier objects has made them immensely popular among amateur astronomers.

Additionally, the Messier catalog is incredibly well-known, to the extent that the Astronomical League (a group of amateur astronomers) has established a unique honor. This award is presented to individuals who are able to successfully locate and identify every single object in the catalog. Participants must complete this task within a specified timeframe, and upon completion, they are bestowed with a certificate and granted membership into the prestigious Messier Club.

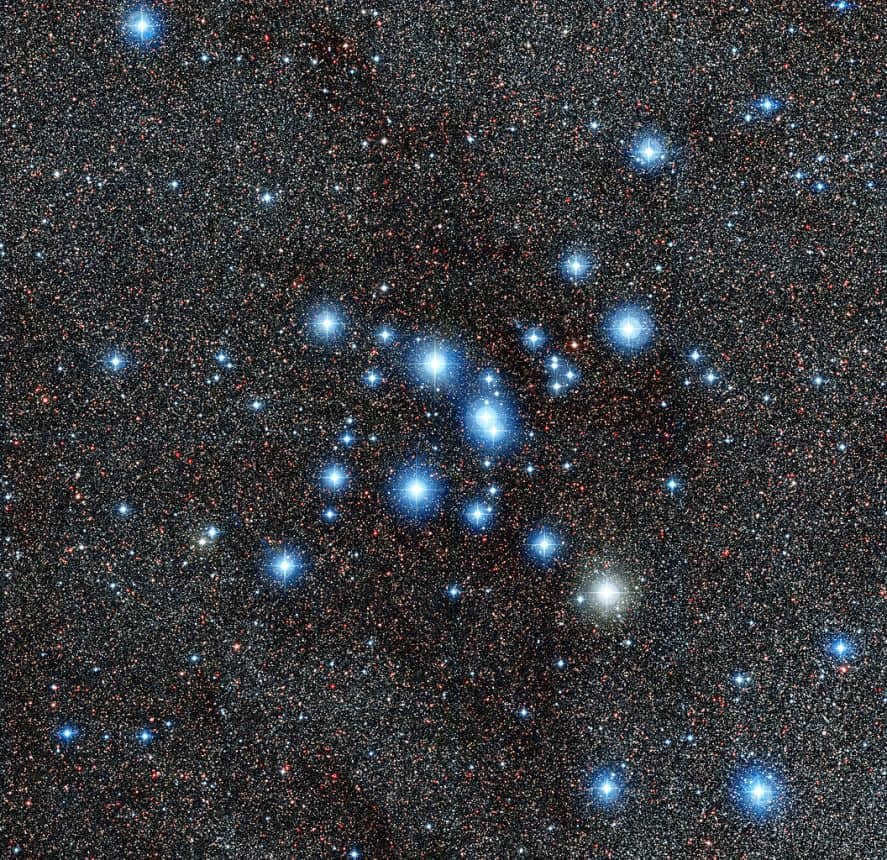

The photograph displays the bright stars that make up the open star cluster M45, which is commonly referred to as Pleiades or Seven Sisters.

While the Hubble Space Telescope has not conducted a comprehensive study of all the objects in the Messier catalog, it has presented an overview of 96 positions as of June 2018. Some images capture the objects in their entirety, while others focus on specific regions.

The Hubble Space Telescope has the capability to enlarge objects effectively; however, its field of view is limited. This means that in certain instances, the telescope must capture numerous frames in order to encompass the entire object. In order to optimize their time, scientists opt to observe only those Messier objects that possess scientific significance. One such object is the Andromeda galaxy (M31). To construct a mosaic image of the Andromeda Galaxy, the Hubble Space Telescope required a staggering 7,400 images (and that’s just for half of the galaxy).

While a digital camera captures a single photo by combining red, green, and blue light to form a complete frame, the Hubble Telescope captures monochrome images at specific wavelengths of light. This enables scientists to analyze the scientific properties of celestial bodies (such as the presence of specific chemical elements).

By combining multiple views at various wavelengths of light, a comprehensive image of the object is created. Each wavelength is assigned a specific color to emphasize different properties of the object.

The Hubble Telescope is equipped to capture infrared (IR) and ultraviolet (UV) observations in addition to visible light. These wavelengths reveal characteristics that are not discernible to the human eye. Special processing is applied to the photographs to represent IR and UV light with distinct colors.

If you opt to embark on a quest for items within the Messier catalog, you can confine yourself to utilizing either a telescope or binoculars. However, the complete array of information will be unveiled when you peruse the awe-inspiring visuals captured by the Hubble telescope. Within this realm, you have the opportunity to marvel at a selection of the finest snapshots from the Messier catalog, all of which have been obtained by the Hubble telescope’s state-of-the-art cameras.

The Hubble Space Telescope has the capability to capture images at various wavelengths of light. It was able to capture the famous Pillars of Creation (M16) in the Eagle Nebula in both visible light (on the left) and with the use of an infrared filter (on the right). The infrared light allowed scientists to study the dense gas and dust within the nebula and discover hidden stars.

One of the initial discoveries made was the remnants of a supernova explosion, which was named the Crab Nebula (M1). Messier and his colleagues continued to search for similar objects, gradually increasing their list to include 110 items, including star clusters, galaxies, and nebulae. The Messier catalog is an invaluable tool for amateur astronomers. In fact, there was even a “Messier Marathon” where participants would stay up all night in an attempt to find the entire list before sunrise.

It is crucial to comprehend that in a photograph, celestial objects in deep space have the ability to manifest themselves in a multitude of hues, while the human eye is incapable of perceiving such a range of colors.

Compilation of objects in the Messier catalog

Displayed in the table below are the coordinates of celestial objects found in the Messier catalog, which are most visible during the four seasons of the year on star maps:

Seasonal Map of Messier Objects

Spring

Summertime

Autumn

Winter

Astronomical Marathon of the Messier Catalog

The Messier Marathon presents an exhilarating test for any stargazer. The objective is to locate all 110 items in the Messier catalog in a single night. Typically, this endeavor is undertaken during the spring equinox, as all objects are visible between sunrise and sunset. The search commences with objects positioned low on the western horizon and progresses towards the east. Naturally, there is no definitive sequential order due to observers being situated in different locations. However, this particular order is ideal for individuals residing in northern latitudes and may vary depending on your specific location.

Frequently, astronomers even form clubs to collectively complete this challenge. Utilize our applications or star charts to expedite your search and locate all the objects on the Messier list.

- Keith contains the Spiral galaxy M 77.

- Pisces is home to the Spiral galaxy M 74.

- The Triangle galaxy M 33 can be found in the Triangle constellation.

- In the Andromeda constellation, you can find the Andromeda spiral galaxy (M 41).

- Andromeda is also home to the elliptical galaxy M 32.

- Another elliptical galaxy, M 110, can be found in Andromeda as well.

- Cassiopeia is home to the open cluster M 52.

- In Cassiopeia, you can also find the open cluster M 103.

- Perseus is home to the planetary nebula M 76, also known as the Little Dumbbell.

- Another open cluster in Perseus is M 34.

- Taurus is home to the open cluster of the Pleiades, also known as M 45 or the Seven Sisters.

- In the constellation Hare, you can find the globular cluster M 79.

- The Orion constellation is home to the Orion emission nebula (M 42).

- In Lrilga, you can find the M 43 emission nebula, also known as Nebula de Mayrand.

- Orion is also home to the M 78 reflection nebula.

- The supernova remnant M1, also known as the Crab Nebula, can be found in Taurus.

- The open cluster M 35 in Gemini.

- The open cluster M 37 in Volopas.

- Open cluster M 36 in Volopasa.

- Open cluster M 38 in Volopasa.

- Open cluster M 41 in the Big Dog.

- Open cluster M 93 in Korma.

- Open cluster M 47 in Korma.

- Open cluster M 46 in Corma.

- Open cluster M 50 in Unicorn.

- Open cluster M 48 in Hydra.

- Open cluster M 44 (Crèche) in Cancer.

- The open cluster M 67 in Cancer.

- The spiral galaxy M 95 in Leo.

- The spiral galaxy M 96 in Leo.

- Elliptical galaxy M 105 in Leo.

- Spiral galaxy M 65 in Leo.

- Spiral galaxy M 66 in Leo.

- The spiral galaxy M 81 (Bode) in the Big Dipper.

- The irregular galaxy M 82 (Cigar) in the Big Dipper.

- The Owl planetary nebula (M 97) located in the Big Dipper.

- M 108, a spiral galaxy within the Big Dipper.

- Situated in the Big Dipper, M 109 is a spiral galaxy.

- The Big Dipper contains the double star M 40 (WNC4).

- Located in the Hound Dog constellation, M 106 is a spiral galaxy.

- Within the Hound Dogs, you can find the spiral galaxy M 94.

- Discover the spiral galaxy M 63 (Sunflower) in the Hound Dog constellation.

- The famous Whirlpool Galaxy (M 51) can be observed in the Hound Dogs.

- A spiral galaxy known as M 101 can be found in the Big Dipper (note that M 102 may duplicate M 101).

- Dragon is where you can locate M 102 (NGC 5866).

- Veronica’s Hair is home to the globular cluster M 53.

- Within Veronica’s Hair lies the spiral galaxy M 64 (Black Eye).

- The Hound Dog constellation contains the globular cluster M 3.

- Look for the spiral galaxy M 98 in Veronica’s Hair.

- Veronica’s Hair is also home to the spiral galaxy M 99.

- Lastly, you can find the spiral galaxy M 100 in Veronica’s Hair.

- Galaxy (S0) M 85 in Veronica’s Hair.

- Galaxy (S0) M 84 in Virgo.

- Galaxy (S0) M 86 in Virgo.

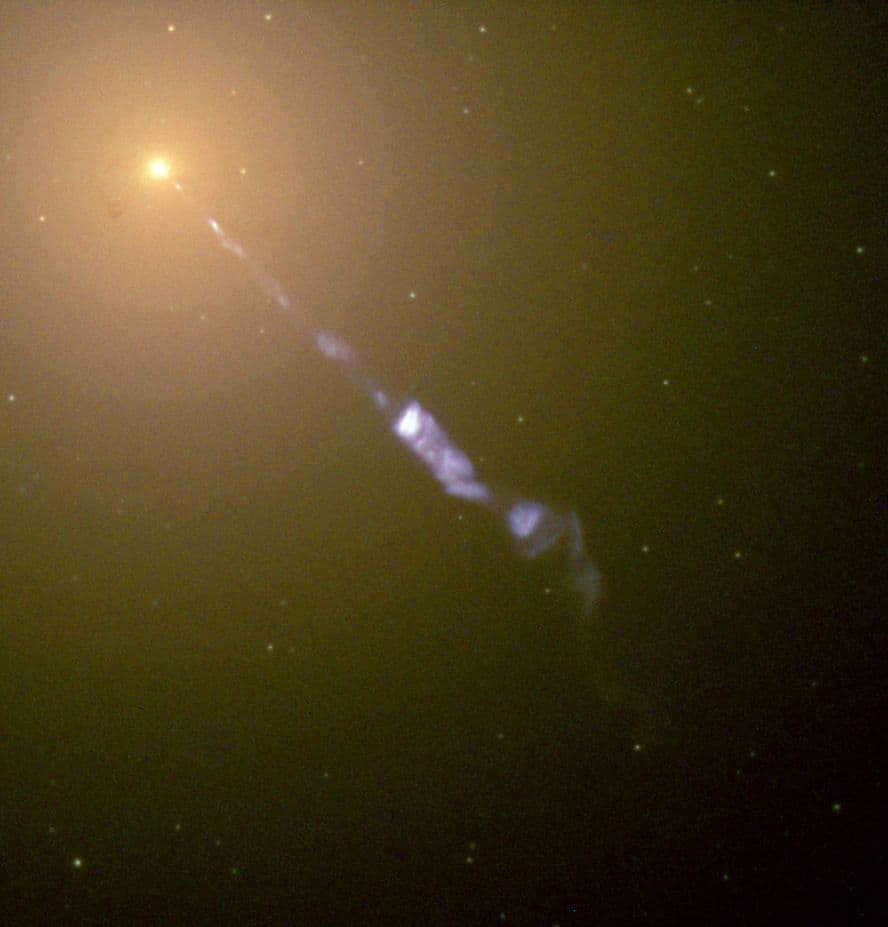

- Elliptical galaxy M 87 in Virgo.

- Elliptical galaxy M 89 in Virgo.

- Spiral galaxy M 90 in Virgo.

- Spiral galaxy M 88 in Veronica’s Hair.

- Spiral galaxy M 91 in Veronica’s Hair.

- Spiral galaxy M 58 in Virgo.

- Elliptical galaxy M 59 in Virgo.

- Elliptical galaxy M 60 in Virgo.

- Elliptical galaxy M 49 in Virgo.

- Spiral galaxy M 61 in Virgo.

- Spiral galaxy M 104 (Sombrero) in Virgo.

- The globular cluster M 68 in Hydra.

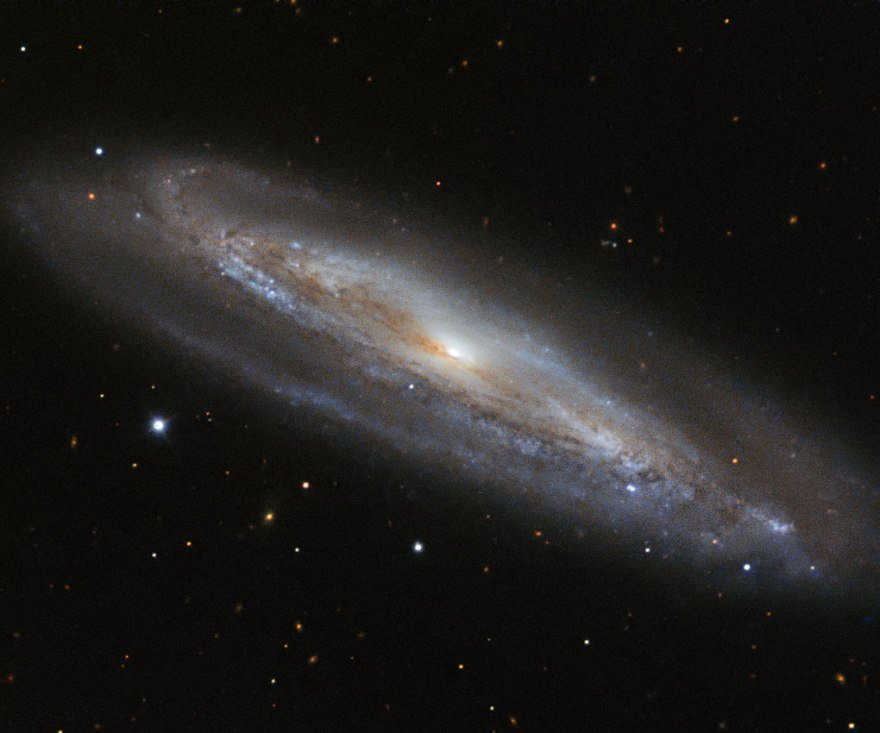

- The spiral galaxy M 83 (Southern Spiral) in Hydra.

- The globular cluster M 5 in the Serpent.

- The globular cluster M 13 in Hercules.

- The globular cluster M 92 in Hercules.

- The planetary nebula M 57 (Ring) in Lyra.

- The globular cluster M 56 in Lyra.

- The globular cluster M 29 in Swan.

- Globular cluster M 39 in Swan.

- The planetary nebula M 27 (Dumbbell) in Foxglove.

- Globular cluster M 71 in Sagittarius.

- Globular cluster M 107 in Serpentor.

- Globular cluster M 10 in Serpentor.

- Globular cluster M 12 in Serpentor.

- Globular cluster M 14 in the Serpentine.

- Globular cluster M 9 in the Serpentine.

- Globular cluster M 4 in Scorpio.

- Globular cluster M 80 in Scorpio.

- Globular cluster M 19 in Serpentor.

- Globular cluster M 62 in Serpentor.

- Open cluster M 6 (Butterfly) in Scorpio.

- Open cluster M 7 (Ptolemy) in Scorpio.

- Open cluster M 11 (Wild Duck) located in the constellation of Shield.

- Open cluster M 26 situated in the constellation of Shields.

- Open cluster M 16 linked to the Eagle Nebula or IC 4703 found in the constellation of Serpent.

- Diffuse nebula M 17 (Omega) located in the constellation of Sagittarius.

- Open cluster M 18 situated in the constellation of Sagittarius.

- Open cluster M 24 (Sagittarius star cloud) found in the constellation of Sagittarius.

- Open cluster M 25 located in the constellation of Sagittarius.

- Open cluster M 23 situated in the constellation of Sagittarius.

- Open cluster M 21 linked to the constellation of Sagittarius.

- Diffuse nebula M 20 (Triple Nebula) located in the constellation of Sagittarius.

- Emission nebula M 8 (Lagoon) found in the constellation of Sagittarius.

- Globular cluster M 28 situated in the constellation of Sagittarius.

- Globular cluster M 22 located in the constellation of Sagittarius.

- Globular cluster M 69 linked to the constellation of Sagittarius.

- Globular cluster M 70 found in the constellation of Sagittarius.

- Globular cluster M 54 situated in the constellation of Sagittarius.

- The Sagittarius constellation contains the globular cluster M 55.

- In Sagittarius, there is another globular cluster called M 75.

- Pegasus is home to the globular cluster M 15.

- Aquarius is where you can find the globular cluster M 2.

- Another globular cluster in Aquarius is M 72.

- However, Aquarius is also home to the open cluster M 73.

- Lastly, the Capricorn constellation houses the globular cluster M 30.

A seven-day extravaganza of the Messier catalog.

Are you prepared to conquer the Messier Marathon? The task of finding all 110 objects in one night can be laborious and sometimes unattainable if you are plagued by light pollution and unlucky enough to reside in an astronomically disadvantaged area. If you’re looking to extend your timeframe, then come join us as we offer a whole week to complete this challenge. An optimal time to commence is a few days prior to the New Moon. Remember to utilize star charts that cover all seasons. Now, let’s keep our fingers crossed for clear skies and embark on this exciting journey!

Evening one.

This week is going to be quite busy. It’s crucial to position yourself away from the lights of the city and begin with Delta Whale. You will encounter your first celestial object, the M77 spiral galaxy, followed by M74 located to the east of Eta Pisces. Both of these objects are visible through a telescope and can be challenging to locate due to their low position in the sky. Proceed westward from Alpha Triangle to find M33. In ideal conditions, you may be able to spot it with binoculars, but the presence of the Moon’s glow or artificial lights will obscure this massive spiral galaxy with its dim surface. To the west of Nu Andromeda, you will find the Andromeda Galaxy (M31). Adjacent to it are M32 (to the southeast) and M110 (to the northwest).

Proceed in a northwestern direction and locate two open clusters in the telescope. Draw a line connecting Alpha and Beta Cassiopeia to locate M52. Then move to the north of Delta and observe M103. Move to the south of Perseus and capture M76 (Little Dumbbell). With binoculars, you will be able to see M34 (located between Algol and Gamma Andromeda).

The sky has become even darker and the fastest objects on the list are situated to the side. Marvel at the Pleiades (M45, also known as the Seven Sisters) high up on the western side (they may appear blue). Leap to the constellation Lepus in the south and find Beta and Epsilon. In that area, you will also come across a small globular cluster called M79 located to the northeast. Behind it, you will find the Orion Nebula (M42) and its adjacent part to the north-northeast, M43. To the northeast of Zeta Orionis in the Orion constellation, you will find the Crab Nebula (M1).

Now it’s time for a break. Treat yourself to a cup of coffee and cozy up. The other items are simple to observe and can be easily opened using binoculars.

Head northwest to observe M35, then venture into the Volopassus and navigate between Theta and Beta. On the eastern side, you can find M37 situated between the two. On the western side, locate Theta and Iota and you will spot M38 positioned in the middle of them, while M36 is found to the southeast. Direct your attention towards Sirius to catch a glimpse of M41 in the southern direction and as you traverse through Korma, you will encounter M93, M47, and M46. Take a deep breath! You have successfully completed today’s checklist.

A total of twenty-four Messier objects have been unveiled to you.

Night two

Are you prepared? Make sure to get a restful night’s sleep tonight, as you have an exciting star race to continue tomorrow.

We’ll begin with four binocular objectives. Create a connection between Sirius and Procyon and, one third of the way through, designate the prominent open cluster M50. Hydra is more challenging to locate, therefore, head southeast from the most luminous star in Unicorn Dzeta and capture M48. To the north-northwest of Delta Cancer is M44. Proceed south and you will discover M67. Through binoculars, it will manifest as a dim hazy area, whereas a telescope unveils a stunning stellar nebula.

You have an opportunity to conquer a Lion, so remember to bring your telescope. Follow the Lion westward until you reach Regulus. Tighten your fist and observe two faint stars. Walk between them and locate M105 (with a magnitude of 9). To the west of M105, you will find two dim galaxies, NGC 3384 and NGC 3389. Behind these galaxies, you will discover M96 in an area devoid of stars.

To the west of M96, you will come across M95. It is essential to use a powerful telescope to observe the expansive arms of this spiral. If you move south of Leo’s hip (Theta), you will notice a star called 73. From there, you will need to move one degree east-southeast to find a pair of objects: M65 to the west and M66 to the east.

In the Big Dipper, we can locate another pair of objects to the west: M81 and M82. To easily find them, you can draw a line connecting Gamma and Alpha stars, and then extend it towards Alpha. Following this line, you will come across these objects. If you have good resolution, you will be able to observe the stunningly bright core of M82. From there, head towards Mirak and continue towards the southeast to find M97, which appears like a scratch in the sky. If you move south towards Fekda and then go 0.5 degrees east, you will come across M109. With enough visibility, you will be able to see the faint bar and the nucleus of this object. Lastly, there is a mistake in the Messier catalogue, as we refer to M40, which is actually a WNC 4 double star.

It is now time to get comfortable in the Hound Dog. Take your bearings from Alpha (Heart of Charles) and Beta. Both are situated to the east of the outermost star in the Big Bucket. In close proximity to Beta, you will spot M106. Concealed within the triangle formed by the stars is M94. Positioned between Carl’s Heart and Eta of the Big Dipper is M63 (Sunflower). Proceed behind Eta, and you will discover M51, with the neighboring star being 24CnV. You will emerge on the “bear” once again and catch sight of M101. Let’s head north and correct another mistake, M102. It is believed to actually be NGC 5866, located in the Dragon constellation to the southeast of Iota.

When observing the night sky, take note of M53 located above Arcturus in Veronica’s Hair, and to the east you will find the impressive galaxy M64, also known as the Black Eye. Lastly, draw a line between Carl’s Heart and Arcturus to locate M3. Well done! You have successfully observed 24 celestial objects once again. It’s only the second day and you’ve already checked off 48 items on your list.

On the third night

I understand that you may be feeling a bit tired, but don’t give in to sleep and miss out on tonight’s observations.

The best time to search for these targets is after midnight, when Veronica’s Hair and Virgo are high in the sky. The objects you will be observing tonight are the brightest of all and will provide you with great satisfaction.

Locate the easternmost star in the constellation Leo, known as Denebola, and form a fist towards the east. M98 can be found to the west of 6 Veronica’s Hair. Return to Denebola and move 1 degree southeast to find M99. Once again, return to 6 Veronica’s Hair and move 2 degrees to the northeast. You will then notice two stars with a magnitude of 5 pointing towards M100, which is the largest galaxy in the cluster and resembles a dim globular cluster with a very bright nucleus. From this point, go north 2 degrees to find 11 Veronica’s Hair, which serves as the next reference point. M85 can be found 1 degree to the northeast of this landmark. Return to 6 Veronica’s Hair once again to locate M99. Take a 15-minute break. You will observe that M88 will begin to elongate, and after 3 minutes, the twisted spiral of M91 will become visible.

Modify your direction. Travel to the east of Denebola and you will come across Epsilon Virgo. Move 4.5 degrees in the opposite direction and you will discover one of the biggest elliptical galaxies, M60. Its brightness level is 9 and it can be observed using binoculars. Additionally, you will notice NGC 4647 in that area, as well as M59 to the west. Continue your journey westward to locate the dimmer M58. One degree to the north lies M89, and 0.5 degrees to the northeast is M90, which has large dust streaks. We proceed across the sky towards the southwest to encounter M87, which is a radio source. There are approximately 4000 globular clusters surrounding it.

A different pair, M84 (west) and M86 (east), can be found at a degree to the northwest. To locate the variable R and M49, follow to the new mark, 31 Virgo. M49 can be found 3 degrees southwest and M61 0.5 degrees south. Finally, locate the brightest Spica and mark your fist to the west to pinpoint M104 (Sombrero).

Hooray! There are 17 more objects to discover. You are halfway there!

Fourth night

Make an effort to wake up early and locate the following targets before dawn. Yes, you will need to wake up at 3:00 a.m. today.

Observe the constellation Raven and proceed 5 degrees towards the south-southeast of Beta. With the naked eye, you can spot the double star A8612. In the nearby Hydra, take note of the compact globular cluster M68, which has a resemblance to a fuzzy star. M83 is hidden 10 degrees southeast of Gamma Hydra. Make sure to wake up early, as it is essential to catch M83 in its high position before time runs out.

By taking a significant leap, we locate ourselves in the southeastern direction of Arcturus and Alpha Serpentis. At a distance of 8 degrees towards the southwest, one can easily spot M5, and beyond that lies the distinctive trapezoidal formation of Hercules along with its northwestern celestial body, Eta. Positioned at a point that is one-third between Eta and Zeta is M13. However, locating M92 can be a bit challenging as there are no prominent stars in close proximity. To overcome this, one can utilize the two northern stars in the “cornerstone” and create an imaginary equilateral triangle. By doing so, a luminous nucleus will come into view.

Proceed in the direction of Sheliak and Sulafat. In the middle, you will come across the small globular cluster M56. Two degrees to the south of Gamma Swan is M29. Move your hand towards the northeast of Deneb and you will discover M39. Head north from Gamma, return to the previously mentioned M27 (Dumbbell Nebula), and then go southwest to locate M71. All of these celestial objects can be observed using binoculars. At present, our list contains 76 entries.

Doesn’t that make you feel enthusiastic? We are approaching the morning skies, which means we will have to wake up very early. When? Two hours before sunrise.

To become acquainted with the intricate constellation of Serpens, locate Beta Scorpius and make a fist while facing northeast. This will lead you to Zeta, which is near the position of M107. From there, go one-fourth of the way back to Beta and observe a row of three stars. Return to Zeta and notice a pair of similar stars in a northeasterly direction. Near the southernmost star in this pair, you will find the globular cluster M10. Move three degrees to the northeast and you will come across M12.

In your search for Alpha in the Serpentine, utilize the “cornerstone” of Hercules to locate Beta and Alpha to the south. Follow the line from the latter and you will discover M14. Southeast of Eta Serpenta is where you can find M9.

To locate M4, we need to focus on Antares. Simply move northwest from the star by 4 degrees, and you will find M80, which may be small but extremely bright. Continuing east from Antares for 7 degrees will lead you to M19, and then if you backtrack and go south by about half a fist’s width, you will reach M62.

Wow, we have completed most of the task and now have a total of 85 objects.

Night six

Still having trouble falling asleep? I understand your frustration, but trust me, these objects are truly captivating and worth the effort.

At the tip of Scorpius, take a moment to appreciate the beauty of Lambda and its neighbor, Epsilon. If you continue in a northeasterly direction, you will eventually encounter M6, also known as the Butterfly. Just below it, you’ll spot a hazy spot called M7, or the Ptolemy Cluster.

To the north, locate the Eagle Lambda and adjacent to it is M11. At the same distance, but in the southwest direction, search for M26. In the obsidian sky, it is possible to catch a glimpse of the Eagle Nebula linked with M16. In the southern direction, M17 (Omega) will catch your attention. In the same southerly trajectory, you will encounter the diminutive assemblage of stars, M18, and further south lies the expansive M24 cloud. Concealed within is the NGC 6603 open cluster.

With a pitch-black sky to the southeast, the M25 open cluster will come into view. Form a fist towards the west and you will stumble upon M23, then descend southward to capture M21. A faint shadow may be discerned on the southwest side. Disregarding it would be a mistake, as you would miss out on M20. With a 4-inch telescope, the presence of dark dust streaks becomes apparent. Shift your binoculars towards the south and fixate on M8 (Laguna Nebula).

If you have kids, take them to this spot that looks like a teapot. The Milky Way comes out of the spout. You’ve explored a total of 98 objects.

Seventh night.

Yes, it has been a challenging week. However, this is the final push, so don’t give up.

The Lambda is located at the top of the teapot. We can use it as a guide to find M28 in the north-northwest and M22 in the northeast. It would be best to switch from binoculars to a telescope now. Zeta is situated at the southeast corner of the teapot. If you move southwest, you’ll come across M54. If you go another 3 degrees further, you’ll spot the fuzzy M70. 2 degrees to the west, you’ll notice another similar area called M69.

Even more fascinating! If you make a clenched hand towards the east-southeast of Zeta, you will come across M55. When dawn breaks, locating M75 will be more challenging. Simply locate Beta Capricorn and head southwest. Look for the stars arranged in a V-shape and move towards the star in the northeast direction. You will easily spot the Square of Pegasus and the reddish Enif. To the northwest of Enif lies M14, and further away is M2.

It would be advantageous if Beta is still illuminating the sky, as you can trace your fist towards the southwest to discover M72 and M73 (to the west of Nu Aquarius). The final object on the list will be M30, which can be found in the south-southwest region of Delta Capricorn.

Congratulations, you’ve accomplished it! You have successfully observed 110 objects within a span of one week. These suggestions serve as a general framework to assist you in determining the optimal time for observation. It is beneficial to acquaint yourself with the characteristics of these objects in advance and gain an understanding of their appearance. Additionally, don’t forget to revel in the beauty of these remarkable structures, as astronomy is meant to be an enjoyable experience.

Messier, known as a skilled hunter of comets, embarked on a mission to compile a comprehensive catalog of celestial objects that were frequently mistaken for comets. In his catalog, he meticulously documented a wide range of cosmic entities, including galaxies, globular clusters, emission nebulae, scattered clusters, and planetary nebulae. During that era, the true nature of these objects remained a mystery, prompting Messier to categorize them simply as nebulae or star clusters.

The initial release consisted of items M1 to M45. The final version of the catalog was completed in 1781 and published in 1784. It was later expanded to include additional objects that had been observed by Messier but were not included in the last edition of the catalog, for various reasons. Many of these objects are still primarily referred to by the numbers assigned by Messier.

Since Messier resided in France, which is situated in the northern hemisphere, only objects north of 35°S were included in the catalog. Consequently, prominent formations like the Magellanic clouds were not included in the list.

Formation of the inventory

In August 1758, while observing comet C/1758 K1, which was discovered by de la Nuit, Messier stumbled upon a nebula that initially deceived him as a comet. However, upon noticing its lack of movement, it became evident that the object in question was not a comet.

Subsequently, in 1801, Messier recollected:

“The motivation behind the creation of this inventory stemmed from a nebula in Taurus, which I came across on September 12, 1758, while observing the comet of that particular year. The nebula’s shape and luminosity were so reminiscent of a comet that I made it my mission to identify similar objects, to prevent astronomers from mistaking them for comets. As I compiled this inventory, my mind was occupied with the use of telescopes specifically designed for comet discovery.”

Messier’s catalog started with his discovery on September 12, 1758, of an object that he designated as number 1. However, Messier was not the original discoverer of this object. According to Arab and Chinese astronomers, it was the remains of a supernova that exploded on July 4, 1054. The object was first observed in 1731 by John Bevis.

The next object in the catalog, M2, was added just two years later on September 11, 1760. Once again, Messier was not the original discoverer of this object. It had been previously observed on September 11, 1746, by Jean Dominique Maraldi.

In May 1764, Messier embarked on a systematic quest to uncover novel celestial bodies resembling comets. He commenced this endeavor by consulting the works of esteemed astronomers such as Hevelius, Huygens, Derham, Halley, de Chéseau, Lacaille, and Le Gentil, meticulously transcribing data regarding the ethereal objects they had previously identified. Messier then proceeded to validate these observations, meticulously measuring the positions of both existing and newly discovered entities – and he did so at a remarkable pace: within a mere six months, the catalog expanded from 2 to 40 objects, with 19 objects being entirely new to Messier’s account.

M41 – M45.

In the early months of 1765, Messier documented M41, a cluster of stars that appears diffuse in the constellation Canis Major, also known as the Big Dog. Following this observation, there was a significant lull in Messier’s record-keeping activities. During this period, he embarked on a journey along the Netherlands coastline, where he made the discovery of new comets. However, he did not add any new objects to his list during this time, most likely because he was contemplating the potential publication of his catalog. It wasn’t until March 1769 that Messier resumed his cataloging efforts and included four well-known objects that were familiar to astronomers. These objects were the Orion Nebula (M42), M43, the Jasli cluster (M44), and the Pleiades, also known as the M45 cluster. It is suspected that Messier included these objects in his catalog to make it more extensive than the one previously compiled by Lacaille, as they clearly did not resemble comets in any way.

The initial version of the catalogue was finished on February 16, 1771, and was published in the same year. It is worth mentioning that in the introduction to this edition, Messier set himself a different and more ambitious objective: to describe all the nebulae that could be seen through a telescope, not just those that resembled comets. However, there were certain well-known nebulous objects that were not included in the catalogue as they could not be mistaken for comets (for example, the h and χ clusters of Perseus) – especially since this approach would not have allowed Messier to reach the “round” number of 50 objects in the catalogue.

M46 TO M52

After finishing the initial version of the catalog, Messier made some new discoveries. On February 19, 1771, he found four additional objects: M46, M47, M48, and M49. The first three were star clusters spread out in the sky, while the fourth, M49, turned out to be a galaxy that belonged to the Virgo cluster.

Later on, on June 6, 1771, Messier found another object, which was eventually cataloged as number 62. Its exact position in the sky was measured much later. The fiftieth object was cataloged on April 5, 1772. It had actually been observed by Cassini before, and Messier had been searching for it since 1764, as he was familiar with the records about it.

On August 10, 1773, Messier made a remarkable observation when he spotted a satellite orbiting the Andromeda galaxy. However, for reasons unknown, he chose not to include this fascinating discovery in his renowned catalog. It wasn’t until 1798 that the news of this finding was finally published, and it wasn’t until much later, in the 20th century, that this object was officially designated as M110.

During his astronomical endeavors, Messier stumbled upon another notable object in 1773, known as M51. It wasn’t until later that Pierre Mechene made the groundbreaking realization that this object was actually comprised of two distinct nebulae. A year later, in 1774, Messier then made the discovery of the diffuse cluster M52, which marked a temporary hiatus in his search for nebular objects.

M53 TO M70.

In February 1777, Messier made the remarkable discoveries of objects M53 and M54. Then, on July 24 of the following year, Messier added M55 to his catalog. Interestingly, Messier had previously attempted to find M55 based on the description provided by Lacaille, who had actually discovered the object.

In January 1779, while observing the comet discovered by Bode, Messier stumbled upon M56. This comet’s path proved to be quite eventful, as it led Messier to discover several other nebular objects. Among them were M57, which had been discovered by Antoine Darquier de Pelepoix, M59 and M60, both discovered by Johann Gottfred Köhler, and M61, which was found by Oriani. Additionally, Messier himself was responsible for the discovery of M58.

M71 – M103.

The second edition of the catalog continued to be updated throughout the year. Over 32 new objects were added, including 5 (M73, M84, M86, M87, M93) discovered by Messier himself and the rest discovered by Méchain (Messier later verified these observations and measured the positions of the objects).

Originally, Messier planned for the third edition of the catalog to include 100 objects. However, by the time the manuscript was ready for printing, Méchain had discovered and described objects up to M103. Additionally, a note in the description of M97 mentioned two more objects, which later became known as M108 and M109. The third edition of the catalog became unavailable in the spring of 1781.

Completion of the catalog

In a handwritten note dated May 11, 1781, Messier made a record of an object that was discovered by Meschen. This object was assigned the number M104. Later on, Meschen also discovered objects M106 and M107.

Despite the addition of these new discoveries, Messier decided to discontinue his work on the catalog. There were a few reasons for this decision. Firstly, Messier experienced a serious accident on November 6, 1781, which required a long period of recovery. Secondly, in the 1780s, the search for nebulous objects was taken over by the English astronomer William Herschel. Herschel utilized much more advanced equipment and was able to discover over 2500 of these objects within a span of 20 years. Messier himself commented on this situation:

After me, the renowned Herschel released a list of the 2,000 nebulae he had examined. By exploring the heavens in his own unique way, using a device with a wide aperture, he found it to be an inefficient method for locating comets. My objective, on the other hand, differs from his: I simply need to locate nebulae that can be seen through a telescope with a focal length of 60 centimeters. In the meantime, I have observed other similar entities. In due time, I will publish details about them, organizing them by right ascension to simplify the search and alleviate any uncertainty experienced by fellow comet hunters.

Nevertheless, no subsequent editions of the catalog were produced.

Messier’s inclusion in the catalog after his death

Although Messier’s catalog originally included 103 objects, it has since been expanded to include 110 objects. This expansion occurred in the 20th century when additional objects observed by Messier were discovered and added to the catalog.

Four objects, M104 – M107, were mentioned in the margins of a copy of the third edition of the catalog owned by Messier. This copy was found and purchased by Camille Flammarion in 1924. Additionally, these objects were referenced in a letter from Messier to Bernoulli, which was published in the Berlin Astronomical Almanac for 1786. The suggestion to include these objects in the catalog came from Helen Sawyer Hogg, who found a reprint of the letter.

Objects M108 and M109 were referenced in a message regarding the description of object M97, and were suggested for addition to the catalog by Owen Gingerich in 1953.

The final entity, M110, the second satellite of the Andromeda Galaxy, was added to the list by Kenneth Glynn Jones, based on the fact that Messier had observed this galaxy as far back as 1773 (the journal containing these observations was only published in 1798, and Messier himself did not deem it necessary to incorporate this object into the catalog).

Despite the overall exceptional accuracy of Messier’s catalog, which is based on meticulous measurements of the exact positions of each celestial object, there are instances where the indicated location does not correspond to any nebular objects. Specifically, there are four entries in the catalog that pertain to missing objects. However, in three of these cases, an object that Messier indeed observed has been identified, albeit at a different location from what was initially recorded in the catalog. This revised information is supported by strong evidence and can be regarded as highly reliable.

M47

Messier’s description of this celestial object is that it is a star cluster without a nebula. Its coordinates are 7h 44m 16s for right ascension and +14° 50′ 8" for declination. However, there are no star clusters in this specific area. In 1934, Oswald Thomas proposed, and in 1959 T. F. Morris confirmed, that the mistake in the catalog was caused by a sign error made by Messier during the calculation of the object’s position. There are actually two entries in the NGC catalog that correspond to this object: NGC 2478 (which is an incorrect location) and NGC 2422 (which is the correct location).

M48

Messier’s description of this celestial object is that it consists of a group of extremely dim stars without any nebulae. It can be located at a right ascension of 8h 2m 24s and a declination of +1° 16′ 42". However, further observations by Oswald Thomas and T. F. Morris have revealed that the object identified by Messier is actually positioned 5 degrees to the north, and it is now identified as NGC 2548.

M91

Messier records this entity as a nebula without stars in the Virgo constellation, with a right ascension of 12h 26m 28s and a declination of -14° 57′ 6". In this area of the sky, there are numerous faint galaxies from the Virgo cluster, but none of them possess sufficient brightness. Owen Gingerich speculated that Messier may have re-observed the object designated as M58 and made an error in his calculations of its location. However, in 1969, W. C. Williams demonstrated that Messier’s mistake was in selecting galaxy M89 as the reference point for his measurements, mistakenly identifying it as M58. Consequently, object M91 should be associated with the catalog entry NGC 4548.

M102

Messier describes this celestial body as a barely visible cloud of gas and dust positioned between the stars ο Volopas and ι Dragon, with a 6th magnitude star in close proximity. The existence of this object has been a subject of debate. While American publications consider it to be non-existent, most European sources identify it as the galaxy NGC 5866.

The controversy surrounding this object stems from the conflicting information from various sources. Messier, who initially reported the observation of this object, later clarified in a letter to Bernoulli published in the Berlin Astronomical Almanac for 1786 that object M102 was actually a re-observation of object M101.

Messier’s catalog

According to modern astronomical classification, Messier’s catalog consists of:

- 6 galactic nebulae

- 28 scattered star clusters.

- 4 planetary nebulae

- 29 globular clusters

- 40 galaxies

- 3 other objects

The Pleiades (M45) is the brightest object in Messier’s catalog with a stellar magnitude of 1.2m. On the other hand, the dimmest objects are M76, M91, and M98 with a stellar magnitude of 10.1m. The Andromeda Galaxy (M31) has the largest angular size measuring 4° × 1°, while the galaxy M101 has the largest linear size with a diameter of 184,000 light-years. The double star M40 has the smallest angular size at 49″, and the planetary nebula M76 has a linear size of 0.7 light-years.

There are a total of 69 Messier objects in our Galaxy. The closest object is the Pleiades, which is located 430 light-years away. On the other hand, the most distant object is the globular cluster M75, situated 78,000 light-years away. Out of these 69 objects, 41 are found outside of our Galaxy. Among these extragalactic objects, 40 are galaxies, while one is a globular cluster known as M54. The farthest object among these is the galaxy M109, which is located 67.5 million light-years away.

Observing Messier objects

It is possible to observe all 110 Messier objects using even the most basic astronomical equipment. Even beginners can easily spot them with a 10-centimeter telescope, and under ideal conditions, all objects (except for M91) can be seen even with 10×50 binoculars.

Light pollution has a significant impact on observations. Many Messier objects can only be seen against a backdrop of dark skies, making them less accessible to astronomers living in urban areas.

Messier objects are primarily observable to astronomers in the northern hemisphere. However, some objects can only be seen at latitudes below 55° (notably M7).

Messier Marathon

The Messier Marathon is a unique challenge where, with a combination of skill and luck, it is possible to observe all 110 Messier objects in a single night. This event has gained popularity among astronomers and stargazers.

To participate in the full marathon, one must be located between 10° and 35° north latitude, as these are the only regions where all Messier objects are visible. It is important to note that the marathon can only be performed twice a year, in March and October, during the new moon phase.

While any observing instrument can be used for the marathon, it is explicitly forbidden to use automatic pointing systems. Additionally, observations made with the naked eye or through a telescope-guide are not considered valid for this challenge.

The first ever complete Messier marathon was accomplished by Jerry Rattley from Arizona and Rick Hull from California, with the latter finishing an hour later than the former. Since the 1980s, over 12 amateur astronomers from the United States have successfully completed the entire Messier Marathon. Among European astronomers, only Petra Saliger and Gernot Stenz, who conducted their observations on the island of Tenerife, have accomplished the full marathon.

In 1774, the renowned French astronomer Charles Messier curated a comprehensive list of captivating celestial objects. Presently, this catalog encompasses 110 astronomical entities, comprising of nebulae, star clusters, and galaxies.

This inventory holds great intrigue as, even 300 years ago, Charles Messier was able to observe these diverse objects with rudimentary telescopes. Today, even amateur telescopes with a lens/mirror diameter of 50 mm or more or a high-quality pair of binoculars can facilitate their observation. If you are yet to acquire a telescope, you can select from our assortment of recommended options. Each of them, given specific conditions, enables the viewing of objects from Messier’s catalog!

It is a fortunate circumstance that many objects can only be observed in the Northern Hemisphere! ))

However, in order to view most of the objects in Messier’s catalog, it is necessary to distance oneself from the bright lights of the city. It is only when one is far away from urban areas that they can truly appreciate the breathtaking beauty of the starry sky.

After gaining some experience in observation, one can gather a group of individuals who share the same passion, venture far away from the city, and organize their very own “Messier Marathon“. This activity is quite popular among amateur astronomers and entails the goal of observing as many objects from the Messier catalog as possible within a single night.

We have decided to initiate a series of posts where we will provide detailed information about each individual object. Let us commence with the inaugural installment.

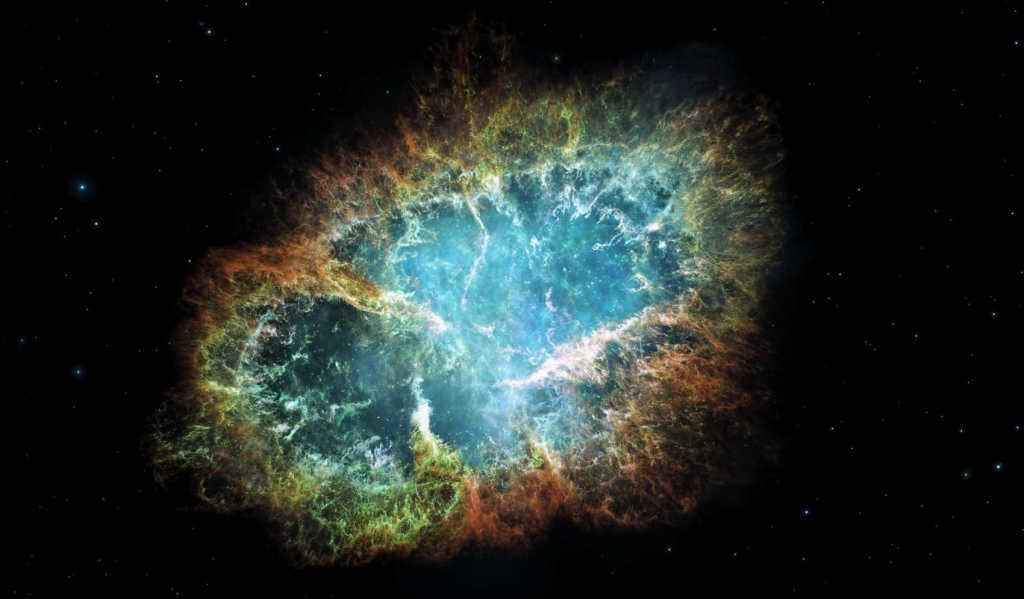

The Crab Nebula (NGC 1952) is designated as M1.

The birth of Messier’s catalog can be attributed to the discovery of this nebula on September 12, 1758. Charles Messier, in his search for comets, came across the Crab Nebula, which shared a striking resemblance in shape and brightness. To avoid any confusion between nebulae and comets in the future, Messier took it upon himself to create his own catalog.

The Crab Nebula originated on July 4, 1054, when a luminous burst illuminated the sky for 23 consecutive days, as documented by both Arab and Chinese astronomers. This extraordinary phenomenon, visible even in daylight, was the result of a supernova explosion. The remnants of this explosion formed what is now known as the Crab Nebula.

John Bavis originally discovered the nebula in 1731. However, it was later rediscovered by Charles Messier in 1758 and included in his catalog.

It is now known as the Crab Nebula. The name “Crab Nebula” was given to it in 1844 when astronomer William Parsons observed a nebula that resembled the shape of a swordtail.

After four years, Parsons created a more elaborate and lifelike sketch, yet the designation had already taken hold. From that point forward, the initial entity in Messier’s inventory, M1, has been known as the “Crab Nebula“.

Observing the Crab Nebula through a telescope

With a decent amateur telescope, it is possible to observe the Crab Nebula. Naturally, it will appear distinct from the images captured by the Hubble telescope. However, under clear skies, you will be able to perceive an elongated diffuse patch.

If you intend to observe from a suburban area, the utilization of supplementary light filters (such as LPR and similar ones) that are designed to combat urban light pollution will enhance the contrast of the image. Nevertheless, the so-called “dipskai” filters (UHC, OIII, H) will not be beneficial in this particular scenario.

Guide to Locating the Crab Nebula in the Night Sky

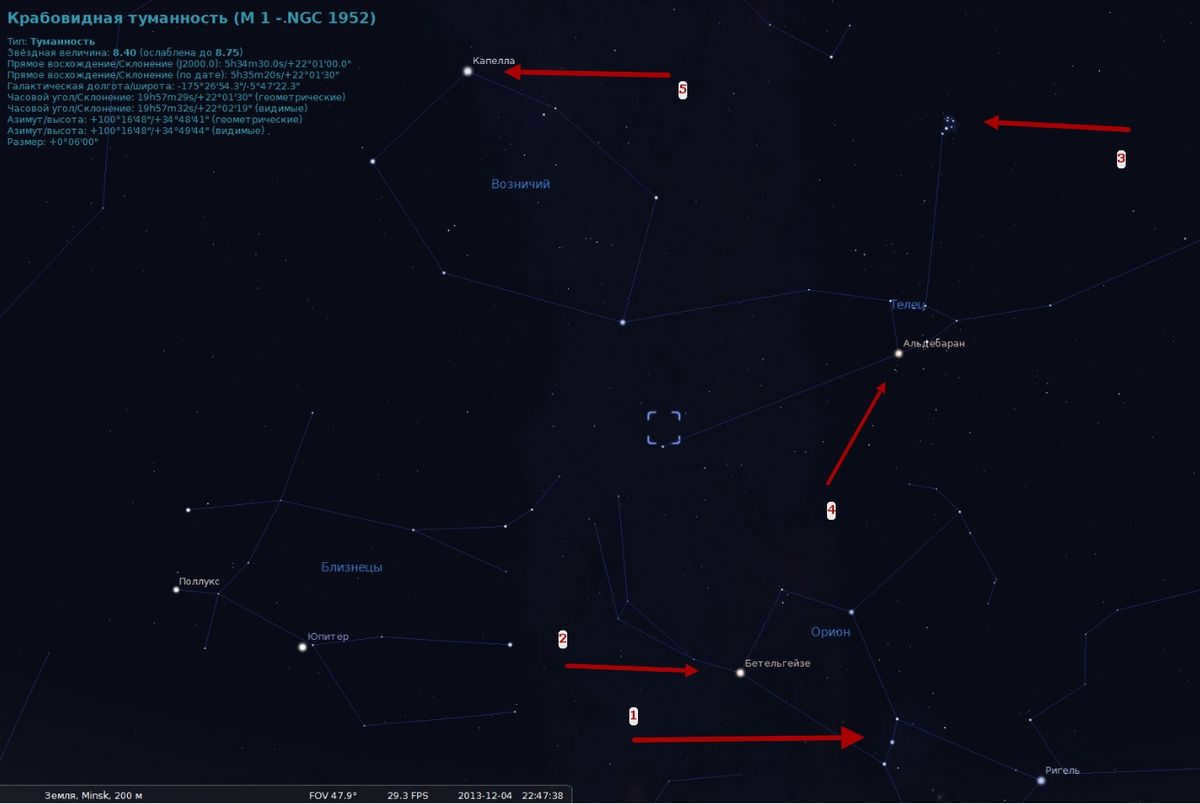

1. The Crab Nebula, also known as M1, can be found in the constellation of Taurus. To begin, let’s narrow down our viewing area.

- In the night sky, we can easily spot the well-known belt of Orion – a trio of stars aligned in a straight line.

- Just slightly above, we will notice the prominent star called Orion’s alpha, which goes by the name Betelgeuse.

- When we direct our gaze upwards, we can observe a cluster of stars resembling a small dipper, known as the Pleiades, located within the Taurus constellation.

- Right below the Pleiades, we can find a bright star named Aldebaran.

- And if we cast our eyes a bit higher, we will come across Capella, which happens to be the most brilliant star present in the Ascendant constellation.

- Observing Aldebaran, which is the most luminous star in the Taurus constellation.

- On the upper left, we can identify Alnas (also known as El-nat or Nat), the second brightest star in the Taurus constellation. Previously, it was mistakenly associated with the Ascendant constellation.

- Below, we have Taurus Tau.

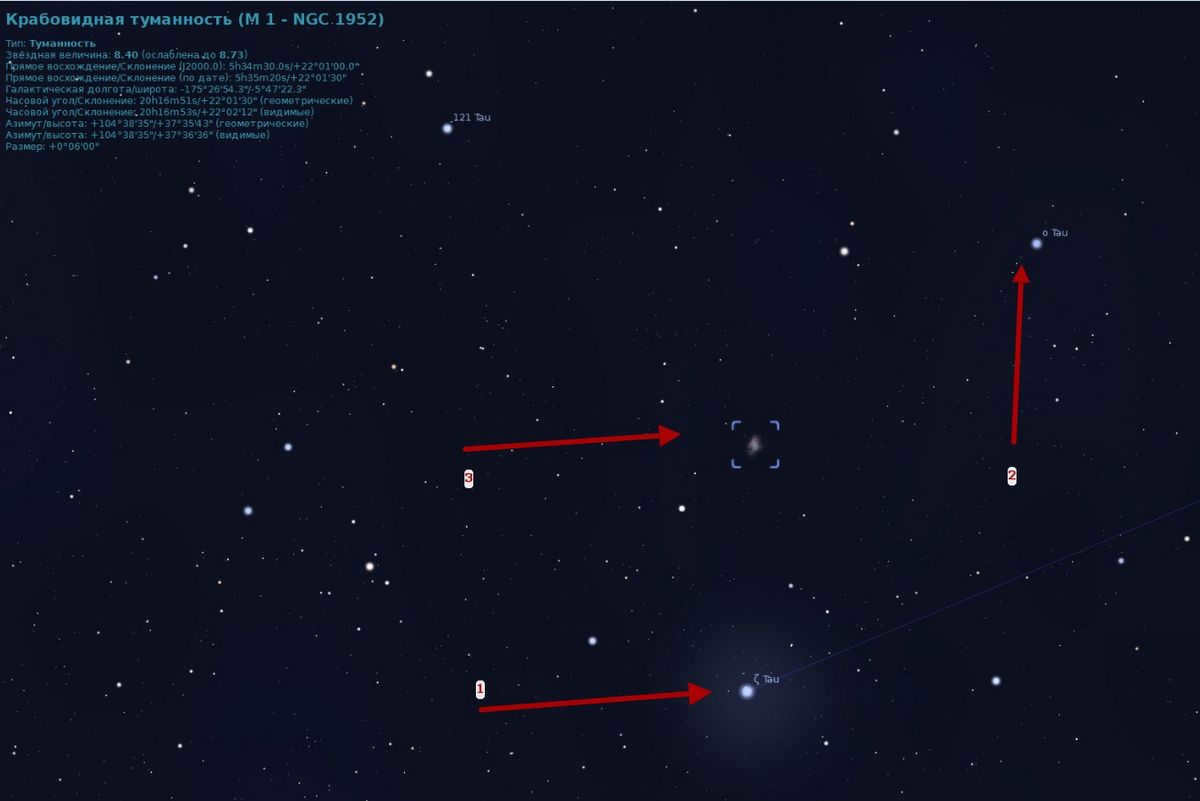

Locate the Crab Nebula in the night sky:

- Direct your attention to Taurus Taurus.

- Another relatively bright star can be seen in the upper-right direction.

- If you look approximately between these two objects, you will discover the Crab Nebula, M1.

For the latest updates on observing techniques and to stay informed about the most captivating events, make sure to follow our Instagram and Youtube channels.

© This text and photo are protected by copyright law. Any use or reproduction of the materials or selection of materials from this website, including elements of design and decoration, is only permitted with the explicit permission of the copyright holder and must include an active link to the source: telescop.by.

Registered in the Trade Register on 25-03-13