When students reach the 2nd grade and start studying the subject “Surrounding World,” one of the constellations they become familiar with is the Big Dipper.

Mastering the skill of locating the star formation known as the “bucket” in the dark sky is crucial for children, as it serves as a guide for spotting numerous other celestial objects.

The Big Dipper is a constellation located in the northern hemisphere and is the third largest in terms of brightness. It is commonly known as Ursa Major, and its seven main stars form a shape that resembles a dipper with a long handle.

Throughout the year, the Big Dipper can be seen in Eastern Europe and all of Russia, except in the fall when it is too low above the horizon in the southern regions of Russia. The best time to observe it is in early spring.

The Big Dipper has been a recognizable constellation since ancient times and holds significance in various cultures. It is mentioned in the Bible and in Homer’s epic poem “The Odyssey,” and its description can be found in the works of Ptolemy.

Ancient civilizations associated this constellation with different objects, such as a camel, a plow, a boat, a sickle, and a basket. In Germany, it is referred to as the Great Basket, in China as the Imperial Chariot, in the Netherlands as the Pot, and in Arab countries as the Grave of the Mourners.

What is the total number of stars in the constellation known as the Big Dipper? There are a total of seven stars and they each have fascinating names in various countries. The people of Mongolia refer to them as the Seven Gods, while Hindus call them the Seven Sages.

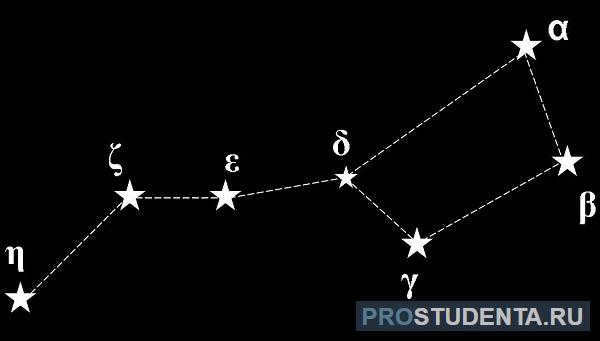

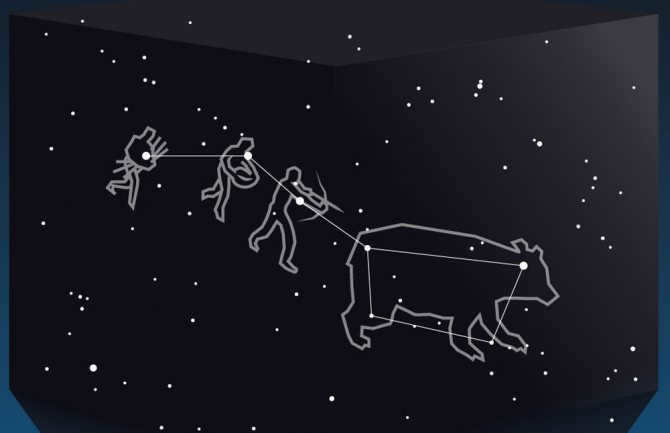

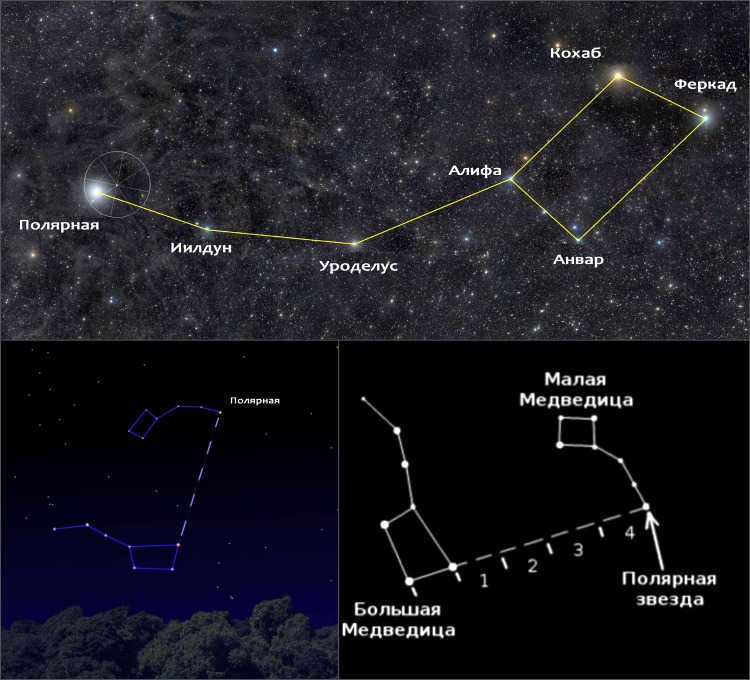

According to Native American beliefs, the three stars that make up the “handle of the dipper” are three hunters in pursuit of a bear. The stars Alpha and Beta of this constellation are also known as the “pointers” because they can be used to easily locate Polaris.

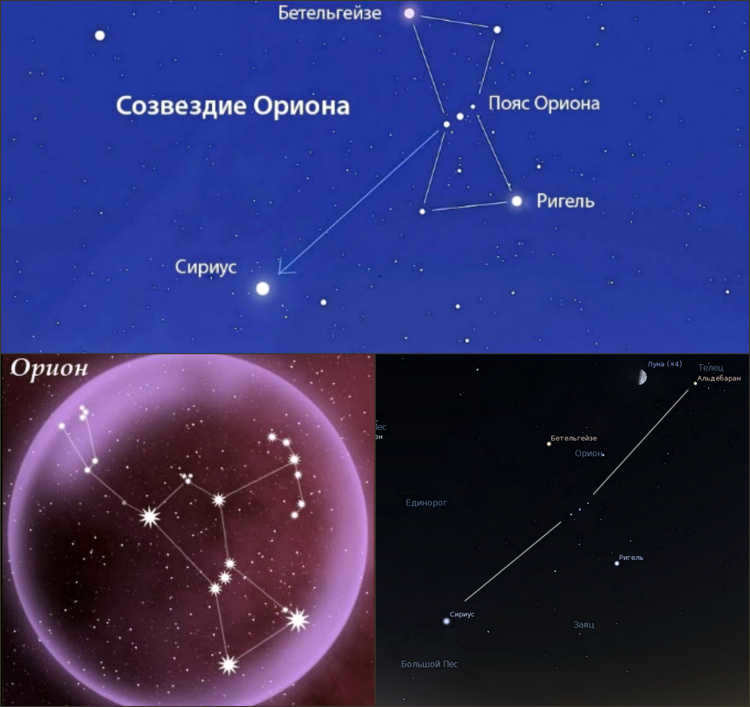

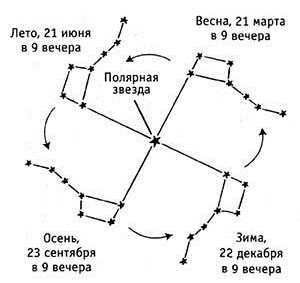

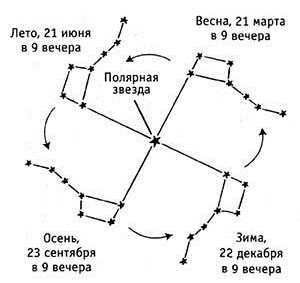

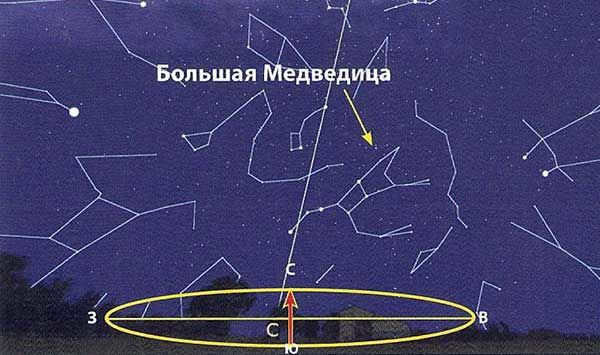

The changing position of the Big Dipper’s bucket throughout the seasons

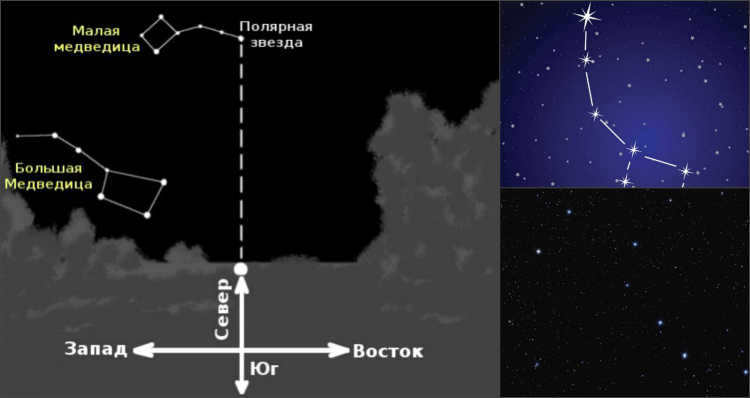

Throughout the year, the bucket of the Big Dipper, also known as the “Bear,” shifts its position in relation to the horizon. To accurately locate it, it is recommended to utilize a compass for improved orientation.

During a clear spring night, the observer can see a cluster of stars directly above. Starting in mid-April, the shape of the stars in the night sky begins to move towards the west. As the summer progresses, the constellation gradually shifts to the northwest and descends. By the end of August, the stars become visible in the northern part of the sky, appearing as low as possible above the horizon.

In the autumn sky, it becomes noticeable that the constellation is slowly rising. According to the diagram below, over the winter months, it moves towards the northeast and rises again by spring, reaching its highest point above the horizon.

To easily locate the constellation, keep in mind that in the summer, it is positioned in the northwest. In the fall, it can be found in the north. In the winter, it is situated in the northeast, and in the spring, it is directly above the observer.

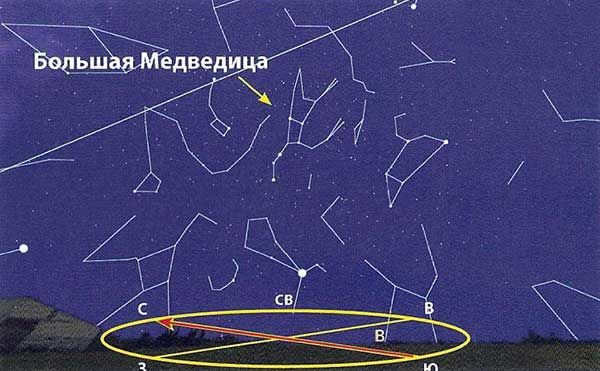

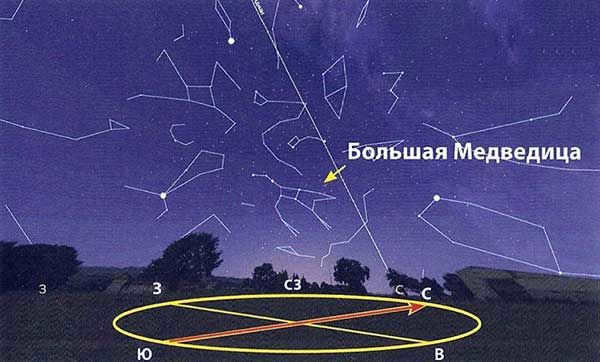

The arrangement of the stellar figure varies depending on the time of day, as well as its own axis, not just in relation to the celestial dome. The image displayed below illustrates that in the evening of January and February, the “bucket” can be found in the northeast (depicted on the right), with its “handle” pointing downwards.

Throughout the night, the constellation follows a semicircular path, reaching the northwest by morning (shown on the left), and the “handle” points upwards.

In July and August, the diurnal changes occur in the opposite direction. The same opposite pattern is observed during the spring and autumn months.

The specific diurnal changes in the constellation’s position in the sky are characteristic of each season of the year.

Stars in the Constellation Ursa Major

When asked about the number of stars in the Big Dipper, astronomers often refer to the 7 most prominent stars that make up the iconic constellation. These seven stars create the distinct shape of the “bucket” and can be easily observed in the dark night sky.

However, in actuality, the constellation is much larger and consists of more stars. The limbs and face of the “bear” are made up of stars with lower brightness.

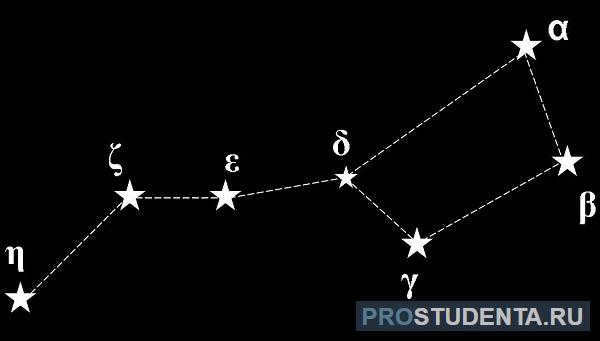

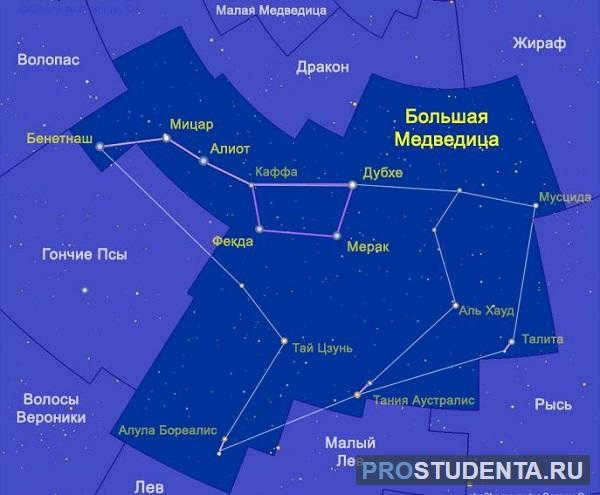

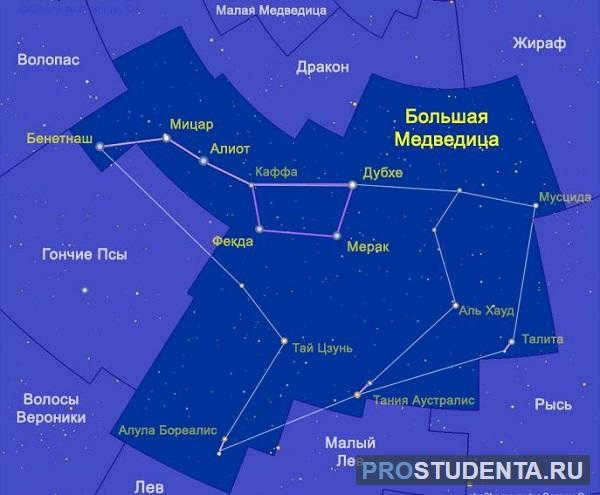

There are seven main stars that compose the constellation:

- Dubhe is the alpha star of the constellation and the second brightest. It is one of the two indicators pointing towards the North Pole. Dubhe is a red giant located 125 light-years away from Earth.

- Merak is a beta star and another pointer to the North Pole. It is approximately 80 light-years away from Earth, slightly larger than the Sun, and emits a strong stream of infrared radiation.

- Fekda, also known as the “hip,” is a gamma-ray dwarf star situated just under 85 light-years away from our planet.

- Megrez is a delta, a blue dwarf located over 80 light-years away from Earth. This celestial object gets its name from being the base of the long tail of the “celestial beast”.

- Aliot, also known as “tail”, is the brightest point in the constellation epsilon. It ranks 31st in terms of visible objects’ luminosity in the sky, with a stellar magnitude of 1.8. This white star is 108 times more luminous than the Sun and is one of the 57 celestial objects used in navigation.

- Mizar, which means “belt” in Arabic, is a zeta star and the fourth brightest in the “ladle” constellation. This star is a double star and has a companion called Alcor, which is less bright.

- Alcaide (also known as “leader”) or Benetnash (also known as “weeping”) is an eta-star that ranks third in luminosity and marks the end of the “bear tail”. It is a blue dwarf star located approximately 100 light years away from Earth.

The constellation contains approximately 125 objects in total.

Among these, it is worth noting three pairs of stars that are located in a straight line and are situated close to each other:

- Alula Borealis (nu of the constellation) and Alula Australis (xy);

- Taniya Borealis (lambda) and Taniya Australis (mu);

- Talitha Borealis (jyota) and Talitha Australis (kappa).

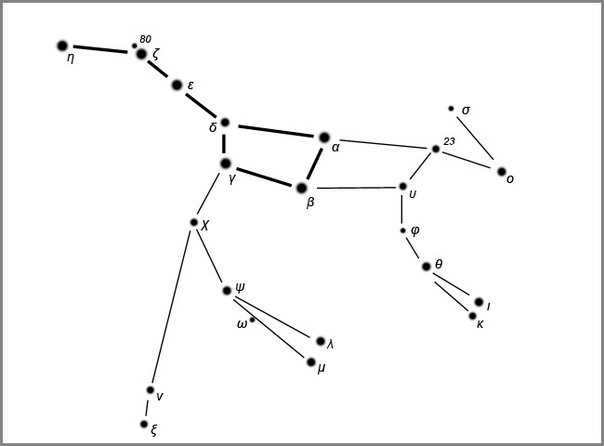

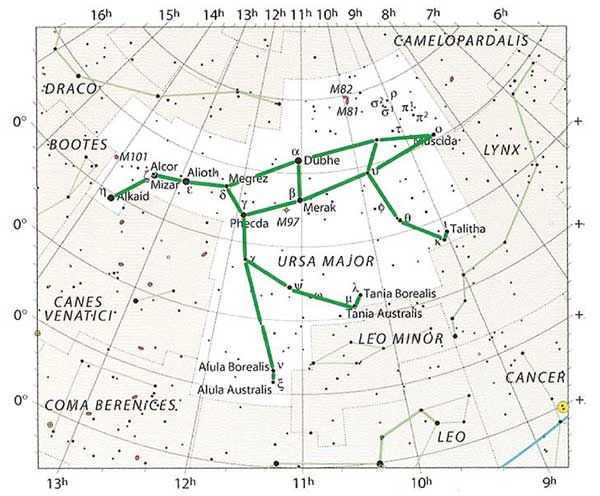

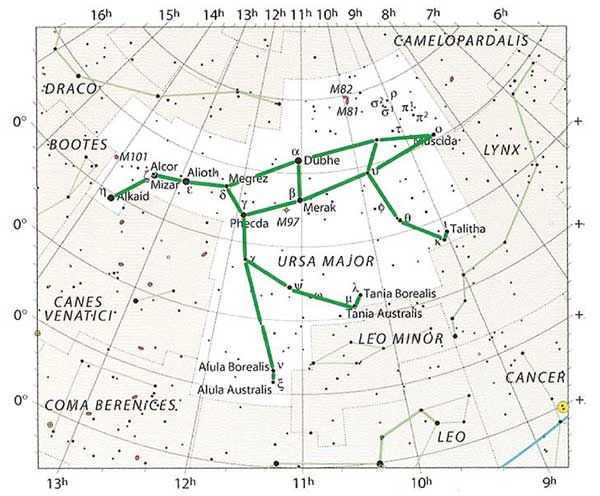

These three pairs are commonly referred to as the “three gazelle jumps,” and they can be found at the bottom of the star cluster in the map below.

The diagram illustrates the positions of the primary seven stars and objects from the Talitha, Tania, and Alula groups.

The name “Big Dipper” for the constellation comes from an ancient Greek myth that provides an explanation.

Callisto, the daughter of King Lycaon, was a nymph renowned for her exquisite beauty and loyalty to the goddess Artemis. However, her fate took a dramatic turn when Zeus, captivated by her charm, disguised himself as Artemis and seduced her. When the real Artemis discovered Callisto’s pregnancy, she was filled with rage and banished the nymph from her presence. Left with no choice, Callisto sought refuge in the mountains, where she eventually gave birth to her son Arkas.

Unfortunately, Callisto’s troubles were far from over. Hera, Zeus’ vengeful wife, learned of Arkas’ existence and punished Callisto by transforming her into a bear. As Arkas grew older, he developed a passion for hunting. One day, while wandering in the mountains, he came face to face with a bear. Little did he know that the bear was his own mother. Ready to shoot his arrow, Arkas was abruptly stopped by Zeus himself.

The primary deity refused to let his offspring carry out a horrifying act, however, he was unable to defy the spell cast by the Hero. Taking pity on the hapless Callisto, Zeus transformed her and her child into celestial bodies and dispatched them into the heavens. Consequently, the constellation Ursa Major materialized in the night sky, accompanied by her son Ursa Minor.

Discovering the Great Bear in the Celestial Sphere

Within the moderate region of Russia, the constellation known as the “Ursa Major” belongs to the group of constellations that never sets, as it is positioned near the North Pole. Locating the “Big Dipper” in the sky during evening and nighttime is a fairly simple task. Observing the star cluster just once is enough to commit its appearance to memory.

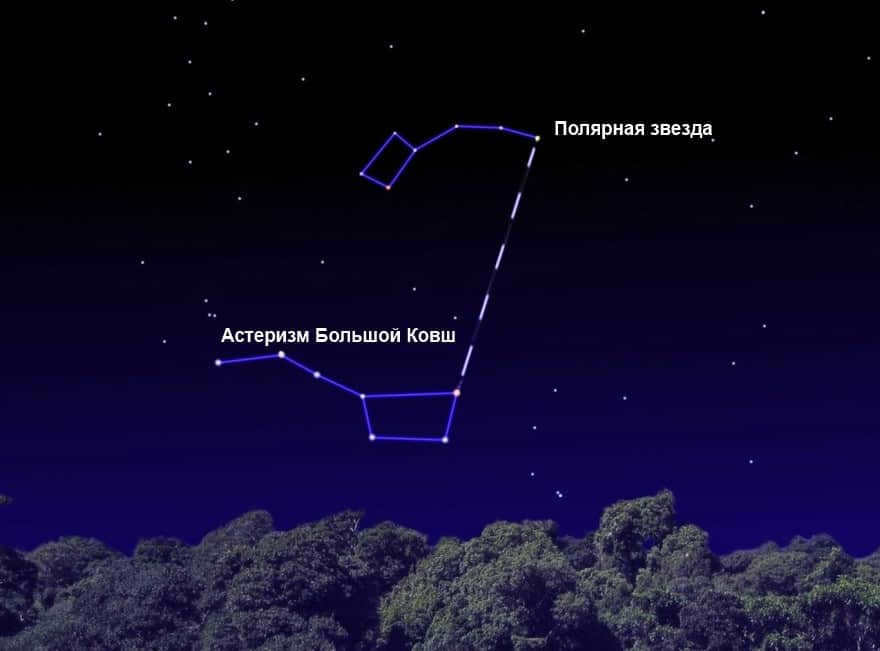

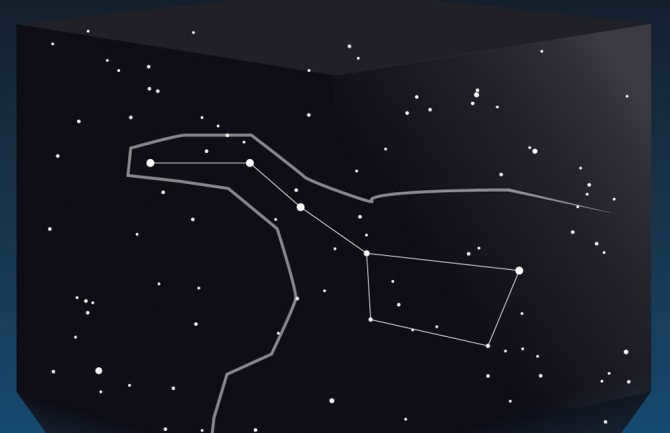

Displayed below is a photograph showcasing the possible appearance of the “Big Dipper” in the nocturnal sky.

For those residing at the latitude of Moscow, the ideal time to observe the star cluster is during the night in April. Between 11 PM and 12 AM, the constellation Ursa Major will be positioned directly overhead. Observers will simply need to connect the stars to form the shape of a ladle.

If it is not April, then the Ursa Major constellation can be found in different parts of the sky:

- In January and February, look towards the northeast with an angle of 30 – 70 degrees above the horizon. The constellation will be oriented vertically.

- In March, look towards the east with an angle of 50 – 80 degrees above the horizon. The constellation will be almost vertical.

- In May, look towards the west with an angle of 60 – 90 degrees above the horizon. The “bucket” shape will be inclined downward by 60 – 80 degrees.

- In June and July, look towards the northwest with an elevation of 40 – 70 degrees above the horizon. The constellation will slope downward by 20 – 60 degrees.

- In August and September, look towards the northwest (closer to the north) with an angle of 20 – 50 degrees above the horizon. The constellation will be parallel to the horizon.

- October – the northern direction, at an angle of 20 – 30 degrees, the “bucket” is tilted upwards by 10 – 30 degrees;

- November-December – towards the northeast (closer to the north), at an angle of 20 – 40 degrees, the figure is tilted upwards by 30 – 80 degrees.

Upon becoming acquainted with the Big Dipper, the opportunities for stargazing expand significantly. Polaris is the initial star that can be located by knowing the position of the large “bucket”. And Polaris (the alpha star of the Little Dipper) serves as the primary celestial reference point in all directions.

Schoolchildren in the 2nd grade are introduced to the Big Dipper constellation during their study of “The World Around Us.”

It is crucial for children to develop the skill of locating the “dipper” in the nighttime sky, as this constellation serves as a guide for identifying numerous other celestial objects.

Overview of the Ursa Major Constellation

The Ursa Major constellation, also known as the Big Dipper, is a prominent feature in the northern hemisphere sky. It holds the distinction of being the third brightest constellation in terms of magnitude. Its recognizable shape is that of a dipper, with seven prominent stars forming the outline of a long-handled ladle.

Throughout the year, the Big Dipper can be observed in Eastern Europe and all of Russia (except for the fall season in the southern regions of Russia, when the constellation is too low above the horizon). The best time to see it is in early spring.

Since ancient times, the Big Dipper has been known to humanity and holds significance in various cultures. It is mentioned in the Bible and Homer’s “Odyssey,” and its description can be found in the works of Ptolemy.

Ancient civilizations associated this constellation with various objects such as a camel, a plow, a boat, a sickle, and a basket. In Germany, it is referred to as the Great Basket, in China as the Imperial Chariot, in the Netherlands as the Saucepan, and in Arab countries as the Grave of Mourners.

According to Native American folklore, the trio of stars that make up the “handle of the dipper” represent three hunters in pursuit of a bear. The two brightest stars in the constellation, Alpha and Beta, are commonly referred to as the “pointers” because they can be used to easily locate Polaris.

The configuration of the Big Dipper varies in different seasons

Throughout the year, the position of the “Bear” constellation changes in relation to the horizon. To ensure accurate navigation, it is advisable to utilize a compass.

During a clear spring night, the group of stars can be found directly above the person observing. Starting from the middle of April, the Big Dipper begins its westward movement. As the summer progresses, the constellation gradually shifts towards the northwest, descending. Towards the end of August, the stars become visible in the northern direction, positioned as low as possible above the horizon.

In the autumn sky, one can observe how the constellation slowly ascends, and during the winter months, as shown in the diagram below, it moves northeast, rising again by spring to its highest position above the horizon.

To easily locate the constellation, it is important to remember that in summer it can be found in the northwest, in the fall it is positioned in the north, in winter it is in the northeast, and in spring it is directly above the observer.

The relative position of the stellar figure in the night sky varies depending on the time of day and its own axis. The illustration below demonstrates that during the evening in January-February, the “bucket” can be found in the northeast (as shown on the right), with its “handle” pointing downwards.

Throughout the night, the constellation traces a semicircle, reaching the northwest by morning (as depicted on the left), and the “handle” extends upwards.

In July and August, these diurnal changes are reversed. The same opposite pattern is observed during the spring and fall months.

Each season of the year is characterized by a specific diurnal change in the constellation’s position in the sky.

The Big Dipper’s Stellar Ensemble

When it comes to counting the stars that compose the Big Dipper, we can identify seven prominent celestial bodies that make up its iconic shape. These seven stars form the distinctive “bucket” that can be easily spotted in the dark expanse of the night sky.

However, in actuality, the constellation is more expansive, comprised of additional stars. The bear’s paws and face are formed by stars of lesser brightness.

The constellation is comprised of seven main stars, which include:

- Dubhe (the alpha star of the constellation, the second brightest. It is one of the two indicators of the North Pole. This red giant is located 125 light-years away from Earth.

- Merak (meaning “lumbar”) is the beta star and the second indicator of the North Pole. It is approximately 80 light-years away from Earth, slightly larger than the Sun, and emits a powerful stream of infrared radiation.

- Fekda (also known as “hip”) is a small star that emits gamma rays and is located approximately 85 light-years away from our planet.

- Megrez (which means “base” in Arabic) is a blue dwarf star that is more than 80 light-years away from Earth. It is called Megrez because it serves as the base of the long tail of the “celestial beast”.

- Aliot (meaning “tail”) is the brightest point of the constellation and is classified as epsilon. It is ranked 31st in terms of luminosity among visible objects in the sky, with a stellar magnitude of 1.8. Aliot is a white star that is 108 times more luminous than the Sun. It is one of the 57 celestial objects used for navigation.

- Mizar (derived from the Arabic word for “belt”) is a zeta star and is the fourth brightest star in the “bucket” constellation. It is a double star and has a companion star named Alcor, which is less bright.

There are approximately 125 objects in total in the constellation.

Among them, we should note three pairs of stars that are located on the same line and are close to each other:

These three pairs are also known as the three gazelle jumps, and they can be found at the bottom of the star cluster in the map below.

The diagram illustrates the positions of the main seven stars and the objects belonging to the Talitha, Tania, and Alula groups.

Myth of the Big Dipper

There exists an age-old legend in Greek mythology that explains the origins of the name given to the constellation known as the Big Dipper.

Callisto, the daughter of King Lycaon, was a nymph renowned for her exceptional beauty and her service to the goddess Artemis. Zeus, captivated by her charm, assumed the form of Artemis and seduced Callisto. Discovering her pregnancy during a bath, Artemis became furious and banished her beloved nymph. Distraught, Callisto sought refuge in the mountains, where she gave birth to her son, Arkas.

Unfortunately, Callisto’s troubles were far from over. Hera, Zeus’ wife, learned of Arkas, her husband’s illegitimate child, and sought revenge by transforming Callisto into a bear. As Arkas grew older, he became an avid hunter. One fateful day in the mountains, he encountered a bear, unaware that it was his own mother. Prepared to shoot an arrow at the creature, Arkas was halted by Zeus himself.

The primary deity refused to permit his offspring to carry out a heinous act, yet he was unable to annul the curse bestowed by the Hero. Displaying compassion towards the hapless Callisto, Zeus transformed her and her progeny into celestial bodies and dispatched them to the heavens. Consequently, the Ursa Major constellation materialized in the firmament, accompanied by her offspring – the Ursa Minor constellation.

How to locate the Big Dipper in the night sky

In the temperate zone of Russia, the constellation commonly known as the “Bear” is classified as a circumpolar constellation, meaning it is always visible near the North Pole. Spotting the Big Dipper in the evening or at night is a relatively simple task. Once you have seen this star cluster, you will easily recognize its distinctive shape.

Shown in the photo below is an example of what the Big Dipper may look like in the night sky.

For those residing at the latitude of Moscow, the optimal time to observe the star cluster is during the night in April. Specifically, between 11pm and midnight, the constellation Ursa Major, also known as the “Big Dipper” or the “ladle,” will be at its highest point in the sky (zenith). To locate this constellation, the observer simply needs to connect the stars to form the shape of a dipper.

If it is not April, the Ursa Major constellation can be found in different areas of the sky:

- In January-February, it can be seen in the northeast with an angle of 30 – 70 degrees above the horizon, and the shape is vertical.

- In March, it can be seen in the east with an angle of 50 – 80 degrees, and the shape is almost vertical.

- In May, it can be seen in the west with an angle of 60 – 90 degrees, and the “bucket” part of the dipper is tilted downward at an angle of 60 – 80 degrees.

- In June-July, it can be seen in the northwest with an elevation of 40 – 70 degrees above the horizon, and the shape slopes downward at an angle of 20 – 60 degrees.

- In August-September, it can be seen in the northwest (closer to the north) with an angle of 20 – 50 degrees, and the shape is parallel to the horizon.

- During October, the northern sky is at an angle of 20-30 degrees, and the “bucket” is tilted upwards by 10-30 degrees;

- In November and December, the northeastern sky (closer to the north) is at an angle of 20-40 degrees, and the figure is tilted upwards by 30-80 degrees.

Once you become familiar with the Big Dipper, your opportunities for stargazing expand significantly. Polaris, the first star you can locate by knowing the position of the big “bucket,” becomes the main celestial reference point in the northern hemisphere.

The clear night sky is like a cosmic encyclopedia, fascinating both astronomers and astrologers. It is filled with countless luminous objects, including well-known constellations. However, in this article, we will focus on one particular constellation, the Big Dipper, and explore whether its visibility is affected by the time of year.

How does the Big Dipper appear?

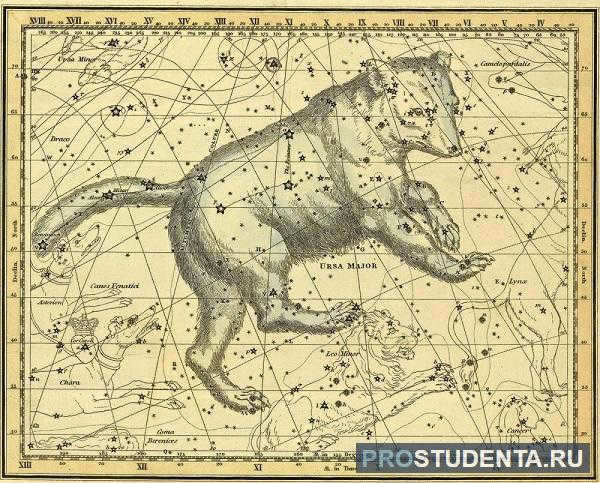

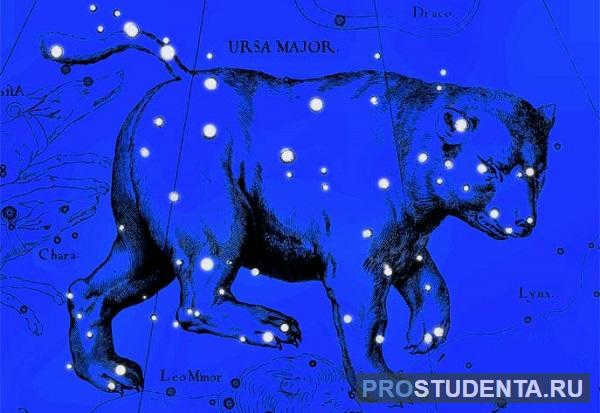

Don’t let the name of this group of distant stars mislead you into thinking they are arranged in the shape of a “bear”. In reality, the constellation was named the Great She-Bear by imaginative individuals. A regular person, upon spotting the brightest part of the figure in the dark sky, would actually see a ladle.

The ladle is shaped like a trapezoidal container with a large handle that extends from the side. Therefore, this astronomical cluster is commonly referred to as the Big Dipper. The tricky part is that the Big Dipper is not the entire She-Bear. To see the whole constellation, one must search for the celestial “dish” itself, along with the branches extending from its corners and the “upper” continuation, or “muzzle”. Only then will we be able to spot the bear. In total, there are 125 luminous points that make up the “bear”! Only an astronomer can identify them all.

How can we locate the Big Dipper?

So where exactly is the Big Dipper located on the bright “map” of the sky? And why is the first step in finding the North Star (Polaris) associated with its bucket-shaped rear end?

Well, it’s not as simple as it seems. The Big Dipper can be found in different parts of the visible sky during different seasons. Read on to learn when and where.

In the summer, it can be seen in the northwest. In the winter, it appears in the northeast. Then it gradually rises up on its hind legs and in the spring, it is directly overhead (at the zenith). Only in the fall does it strictly appear in the north (the star “dish” in our latitudes acts as the compass needle at this time of year). Additionally, in the northern hemisphere, you can use the Big Dipper to determine the time of day.

How to Discover Stars Beyond the Big Dipper

If you are familiar with the appearance of the Big Dipper, you can also locate other bright celestial objects in the visible universe. One such object is the constellation of the Little Bear. Simply imagine a straight line connecting the outermost stars of the Big Dipper. Extend this line until you reach a point with the same level of brightness as the stars in the aforementioned cluster. This point is known as Polaris, which represents the far end of the handle of the Little Dipper. Polaris also serves as a guide to the North Pole, hence its name. Interestingly, Polaris is often difficult to see in the northern regions due to the presence of the white polar nights.

- Cassiopeia. Mizar is located as the second star from the end of the “handle” of the bucket. By drawing an imaginary line through Mizar and Polaris, you can find the well-luminous letter W.

- Leo. During the months of February and March, you can draw a line through all sides of the bucket’s wall, where its “handle” is attached. This straight line will lead you to a clearly visible band.

- Virgo. By continuing the line from Mizar, which passes through the end of the “bear-bucket” handle, you will come across another bright light called Alkaid. Further to the right and left, you will find Alfessa and Arcturus respectively, at a more reasonable distance. By looking along the line through Arcturus, you can reach Virgo.

- Ascendant. Continuing the constellation of the Little Bear towards Polaris, we follow the line we have created as far as we can. Up to the first star of equal brightness. This star is part of the same pentagon, which has the same level of luminosity. Inside the pentagon, we can see the figure of a shepherd with a staff, or perhaps his figure with goats (the imagination of the ancients knows no bounds). In Latin, this cluster is called Auriga. The brightest star in this constellation is Capella.

Let me clarify that there are a total of 88 constellations. However, there are also some stars that are visible to the naked eye – Arcturus (which has already been mentioned), Capella, and Spica. Capella can be seen in the middle of summer in Volgograd, Saratov, and Samara. It shines the brightest in the constellation of Ascendant. Now let’s talk about Spica. To locate it, you need to follow an arc path through three stars in the “handle” of the Big Dipper. Two of these stars, Mizar and Alcaide, should be familiar to you. The orange star Arcturus can be found further along this path (refer to the section about the Virgo constellation). Continue mentally extending the arc until you reach the brightest point.

The dark sky is adorned with countless stars, although the human eye can only perceive approximately 6000 distant luminaries. However, navigating through them is no easy task. Throughout history, astronomers from various cultures have created constellations based on their legends, beliefs, and understanding of the world. These constellations often transform familiar asterisms, or groups of bright stars, into various shapes and forms. For instance, the renowned Big Dipper in the constellation Ursa Major was not always associated with a dipper or a bear.

Egypt

Bull’s limb

Facts and Location of the Big Dipper Asterism

The Big Dipper asterism is located in the second quadrant of the northern hemisphere (NQ2) and can be observed at latitudes ranging from +90° to -30°. It is most visible in the month of April. This group of stars is circumpolar in many parts of the northern hemisphere, meaning it remains above the horizon at all times. Due to the rotation of the Earth, the Big Dipper appears to slowly move counterclockwise around the north celestial pole.

In various seasons, the Big Bucket asterism can be observed in different regions of the celestial sphere. During the spring and summer months, it is positioned at a higher altitude, whereas in the fall and winter it is located closer to the horizon. The configuration of the asterism can exhibit significant variations. For instance, during the fall season, it seems to be resting on the horizon, while in the winter, the handle extends beyond the bowl. In the spring, it appears to be inverted, and in the summer, the bowl tilts towards the Earth.

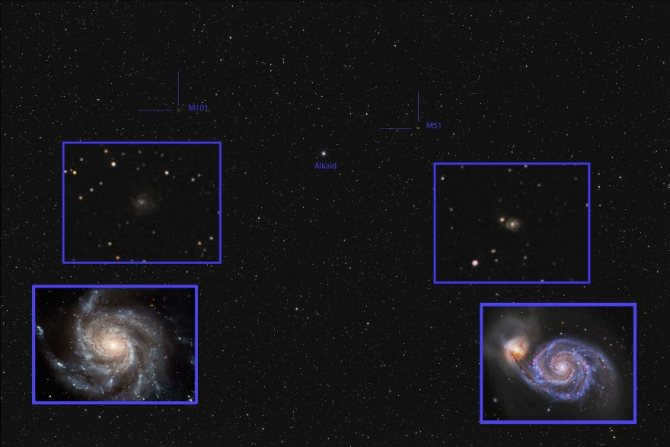

The Big Bucket asterism is situated in a region that contains several remarkable celestial objects. Among them are the Whirlpool Galaxy (Messier 51), the Whirlpool Galaxy (Messier 101), the double star Messier 40, a spiral galaxy known as Messier 81 (Bode Galaxy), an irregular galaxy called Messier 82 (Cigar), a planetary nebula named Messier 97 (Owl Nebula), and the spiral galaxies Messier 108 and Messier 109.

The asterism within the constellation of the Big Dipper plays a significant role in the navigation and identification of other prominent stars. By following the handle of the Big Dipper, one can locate the star Arcturus (also known as Volopassus), and continuing along the line will lead to the star Spica in the constellation of Virgo. The two stars that form the bowl of the Big Dipper point towards the North Star, Polaris, while the stars Megrez and Fekda direct attention towards Regulus in the constellation of Leo, which is not only one of the brightest stars in the night sky, but also towards Alfard in the constellation of Hydra. Following the line from Megrez to Dubhe will guide you to the star Capella (also known as the Ascendant), and from Megrez to Merak and Castor in the constellation of Gemini.

Over the course of 50,000 years, the stars comprising the Big Dipper will gradually shift their positions, resulting in a change in the overall shape of this well-known asterism. However, due to the fact that the majority of these stars belong to the Moving Group of stars within the Big Dipper (with the exception of Alcaid and Dubhe), the overall pattern will not undergo a dramatic transformation. This familiar pattern will continue to persist for another 100,000 years, although the handle of the Big Dipper will continue to undergo further changes.

To find Polaris, you can visualize a line from Merak to Dubhe and then mark that line 5 times.

If you have located the Big Dipper, locating Polaris becomes an easy task. It is situated in the Little Dipper. The Big Ladle revolves around the north pole and always points towards Polaris.

China

The carriage of Emperor Shandi

In ancient China, astronomers had a unique way of dividing the sky. They divided it into 28 vertical sectors, known as “houses,” which the Moon would pass through each month. This system was similar to the Western astrology’s division of the sky into 12 signs of the Zodiac, which was borrowed from the Egyptians. At the center of the sky, like an emperor in a capital city, the Chinese placed Polaris, which had already taken its usual place. The seven brightest stars of the Big Dipper were also nearby, within the Purple Enclosure, one of the three Enclosures that surrounded the palace of the “royal” star. These stars could be referred to as the Northern Bucket, as their orientation corresponded to the seasons, or as part of the carriage of the Heavenly Emperor Shandi.

Alina Yeremeeva

, historian of astronomy, senior researcher at the Moscow State University:

"In the ancient Chinese records of the III millennium BC, there are detailed observations of the stars in the constellation known as the Big Bucket. These observations revealed a noticeable change in the position of the handle during the evening. At that time, the pole was located near the alpha star of the Dragon, and the Bucket appeared to rotate around it, with different orientations in different seasons. By closely examining this rotation, one can easily see a possible origin of the swastika symbol, which represents eternity and the constant passage of time. The traditional design of the compass, one of China’s main inventions, further supports this theory as it resembles a ladle with a handle pointing south. I believe that understanding the true meaning behind this ancient symbol will help restore its reputation, which has been tarnished by its association with fascism."

Logline

The starry sky can be seen as a chaotic picture, with scattered stars that require a developed imagination to see human figures, animals, and objects. However, there are some stunning star patterns that are captivating in their own right! One of these patterns is the famous Big Dipper, which serves as a main landmark in our sky. It is important to note that the Big Dipper is not a constellation itself, but rather a part of the Big Dipper constellation. So, how can we locate the entire Big Dipper in the sky?

The solution is simple: by following the shape of the ladle!

Also read: Variable stars. History of discovery In 1572, the renowned Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe observed the first recorded phenomenon of a supernova outbreak.

But first, let’s find the ladle itself.

The best time to locate the ladle of the Big Dipper is during the late summer and autumn seasons, when it is situated in the northern region of the sky during the evening hours. Wondering where exactly north is? North can be identified as the portion of the sky where the Sun is never present! (Unless, of course, you reside above the Arctic Circle.) Determining the direction of north is a simple task on a clear day: at noon, the Sun is approximately positioned towards the south, thus indicating that north lies in the opposite direction.

Therefore, during the autumn season, the Big Dipper can be found in the northern part of the sky. Its location is easily discernible due to its relatively low altitude and its customary horizontal arrangement.

In autumn evenings, the Great Bear can be found in the northern sky. Image: Stellarium

During the winter months, particularly in January and February, the constellation resembling a ladle starts to move upward in the night sky, appearing as if it’s standing on its handle. This phenomenon is not surprising, considering that every day, all the stars are observed to rotate around the celestial pole, indicating the Earth’s rotation on its axis. However, over the course of a year, the stars also make an additional circular motion, reflecting the Earth’s movement in its orbit around the Sun. The stars of the Big Dipper follow this pattern as well, shifting from their lowest point during the second half of winter and appearing “on the fringes”. During this time, in the evenings, the Big Dipper can be found in the northeast direction.

During the winter evenings, you can observe the Big Dipper in the night sky. This constellation, also known as Ursa Major, is easily recognizable due to its distinct shape. The image above shows the Big Dipper as seen through the Stellarium software.

As spring approaches, the Big Dipper gradually shifts its position in the sky. By early spring, it appears in an upright position, and by mid-spring, it reaches its highest point above the horizon. However, if you are facing south, the orientation of the constellation appears inverted. This can make it challenging for beginners to locate the ladle-shaped asterism in the springtime.

During the spring season, the Big Dipper can be seen at its highest point in the night sky. When observing it from a southern perspective, the shape of the ladle appears to be inverted. This phenomenon can be visualized using the Stellarium software.

However, in the northern regions of Russia and in areas with temperate latitudes, the ladle is not easily visible due to the presence of white nights. On the other hand, in the central and southern parts of Russia, the Big Dipper can be observed clearly in the western direction and, after midnight, in the northwest. During this time, the orientation of the ladle is tilted, with the ladle portion pointing downwards and the handle pointing upwards.

The position of the Big Dipper in the summer sky can be easily identified by looking for the ladle-shaped pattern. This well-known constellation occupies a much larger area in the sky than just the ladle itself.

Surprisingly, the Big Dipper extends beyond the ladle and covers a vast portion of the sky below and to the right of it. In fact, this constellation ranks third in terms of size among all 88 constellations, only surpassed by Hydra and Virgo.

The Great Bear is an incredibly expansive constellation, encompassing a much larger region in the night sky than the Great Dipper. In this illustration, the boundaries of the Great Bear are highlighted with a dashed red line. Illustration: Stellarium

The Great Bear consists of a total of 125 stars that are visible to the naked eye under ideal conditions of a dark and clear sky. In a typical urban sky, you can spot a few stars from the Great Bear in addition to the stars of the Dipper.

How can you locate these stars? Take a close look at the Dipper. To its right, you will notice two more stars that are nearly parallel to Dubhe and Merak. These stars are 23 and upsilon (υ) of the Great Bear. Further away, you will find the omicron (ο) star of the Great Bear.

To the right and below the Big Dipper, you can observe a distinct triangle formed by the stars theta (θ), kappa (κ), and iota (ι). Another similar triangle can be seen below the dipper, consisting of the stars lambda (λ), mu (μ), and psi (ψ).

The two triangles resemble the front and back paws of an animal. In this case, the dipper represents the bear’s torso, and the handle of the dipper symbolizes its long and curved tail. (The origin of such a lengthy tail for a bear is a separate tale.) Finally, the omicron star serves as the head, possibly even the nose, of the creature.

Undoubtedly, one can already identify a bear in this depiction!

If you gather all the major stars in the Big Dipper constellation, not just the stars of the dipper itself, they do indeed bear a resemblance to a quadruped creature from a distance. Illustration: The Vast Universe

Lastly, two additional stars, nu (ν) and xi (ξ), of the Big Dipper are positioned one below the other in the southernmost part of the constellation. They are positioned so far south compared to the other stars that at the latitude of Moscow, for example, they dip below the horizon when the Big Dipper is in the northern sky.

The Big Dipper constellation is rightfully regarded as the primary constellation in the Russian night sky. Firstly, its primary formation, the Big Dipper, never dips below the horizon and can be observed at any time of the year. As a result, it serves as an excellent navigational guide. It can be easily utilized to locate

- One can use Polaris to navigate in space;

- Cassiopeia is a constellation;

- The constellation of Leo is the primary constellation in the spring sky;

- Arcturus and Capella are two bright stars, with one shining in the spring-summer sky and the other dominating the winter sky along with the magnificent winter constellations;

- Gemini is a constellation with two brightest stars, Castor and Pollux;

- The spring sky includes the star Spica and the constellation Virgo;

I hope you found this article interesting.

India

The Seven Wise Men

Observational astronomy in ancient India did not reach the same level of excellence as mathematics. It was heavily influenced by both Greece and China. For instance, the 27-28 “stands” (nakshatras) that the Moon passes through in about a month bear a strong resemblance to Chinese lunar “houses”. Hindus also placed great importance on Polaris, which, according to the Vedas, is the dwelling place of Vishnu himself. The Bucket asterism located below it was believed to be Saptarisha – seven sages who were born from Brahma’s mind and are considered the forefathers of our current era (Kali-yuga) and all beings living in it.

Therefore, there are precisely seven bright stars in the bucket of the Big Dipper. Two of these stars can act as a guide for travelers. The idea is that these stars make it easy to locate the most renowned star in the entire world – Polaris. Locating Polaris is a simple task. All one needs to do is visualize a line connecting the two outer stars of the Big Dipper’s bowl. Next, one should estimate the distance between these two stars. Polaris is situated just above the North Pole.

In ancient times, when there were no navigational instruments, the Big Dipper served as a crucial landmark for navigators and travelers. Therefore, if you ever find yourself in a challenging situation in an unfamiliar area, simply turn to the constellation of the Big Dipper. Within it, you will find Polaris, which will guide you towards the north. This unassuming celestial object, although small and not particularly bright, has proven to be a lifesaver for those who have lost their way in the taiga, the desert, or at sea. Polaris leads the way for its closest counterpart, the Little Dipper. Both of these “animals” are situated in the vicinity of the North Pole, as classified by astrologers.

Greece

Ursus

The Great Bear is one of the 48 constellations recorded in Ptolemy’s star catalog around 140 BC, although its existence is mentioned even earlier, dating back to the time of Homer. Intricate Greek legends provide various explanations for its formation, although they all agree that the bear represents the beautiful Callisto, a companion of the goddess of hunting, Artemis. According to one narrative, employing his typical methods of reincarnation, the amorous Zeus seduced her, resulting in the wrath of his wife Hera and Artemis herself. To save his lover, the god of thunder transformed her into a bear, who roamed the mountain forests for many years until her own son, fathered by Zeus, encountered her while on a hunting expedition. The supreme deity had to intervene once again, preventing the killing of the mother by her own child, and brought both of them up to the heavens.

The Big Dipper is a well-known constellation located in the northern hemisphere. This constellation is made up of seven stars that create a prominent figure in the night sky. It takes the shape of a dipper, and its two outermost stars, Dubhe and Merak, are used to locate the North Star, Polaris. The brightest star in the Big Dipper is Aliot, and one of its most famous features is the double star system known as Mizar and Alcor. Mizar is often referred to as the “horse,” while Alcor is known as the “rider.” Those who are able to distinguish between these two stars are believed to have exceptional eyesight.

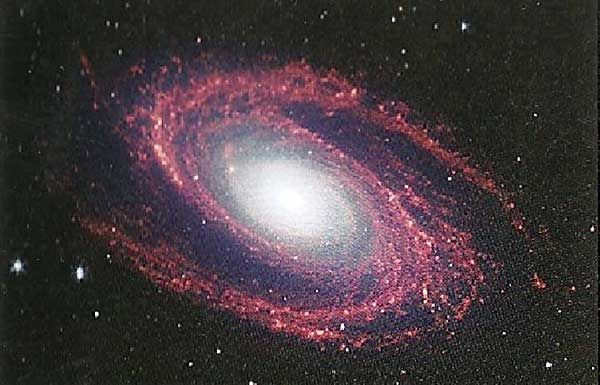

There are two spiral galaxies, M81 and M101, that can be observed in the Big Dipper constellation using a small telescope. M81 is particularly fascinating as it bears a striking resemblance to our own Milky Way galaxy. In close proximity to M81 is the smaller galaxy M82, which experienced a powerful explosion just a few million years ago. This event is of immense significance in the field of astronomy as it provides valuable insights into the formation and evolution of galaxies.

The composite image of spiral galaxy M81 was created by combining ground-based and space-based images.

One more fascinating phenomenon in the Big Dipper is the M97 planetary nebula, known as the “Owl” due to its resemblance to the bird. It can be observed using a small telescope, as the nebula’s total brightness is 11″. According to Greek mythology, Artemis, the young goddess of the hunt, used to roam the mountains and forests in search of game. One of the most captivating members of Artemis’ entourage was her maid, Callisto. When Zeus (known as Jupiter in Roman mythology) saw the nymph, he was captivated by her beauty and youth. However, Artemis’ handmaidens were not allowed to marry. In order to possess Callisto, Zeus used cunning and disguised himself as Artemis. Zeus succeeded, and Callisto gave birth to a son named Arcadus, who quickly grew up to become an exceptional hunter.

Also check out: Constellation Eridanus Constellations ContentsMain stars of the constellation EridanusExciting objects to observeSpotting the constellation in the night skyBackground of the constellation EridanusEridanus is a constellation located in the southern hemisphere, ranking as the sixth largest in that part of the world.

Locating the constellation in the celestial sphere

The constellation can be spotted at latitudes ranging from -30° to +90°. The prime period for observing it is during the spring season, particularly in the months of March and April. Throughout Russia, the constellation is prominently visible to the naked eye. Among its neighboring constellations are Draco, Camelopardalis, Lynx, Leo Minor, Leo, Coma Berenices, Canes Venatici, and Vulpecula. Among the most well-known constellations, the Big Dipper stands out as one that skygazers can effortlessly identify. This constellation in the northern hemisphere features stars that form a distinctive shape resembling a dipper. During autumn, it can be found in the northern region of the sky.

During the winter season, the Big Dipper shifts its position towards the east, causing the “handle of the bucket” to descend. This movement gives the impression that the Bear is gradually ascending into the celestial realm. Many people are familiar with the technique of locating Polaris, the North Star, by using the two right-most stars of the Big Dipper’s bucket as a guide.

During the spring season, the Big Dipper starts its descent from the sky and moves towards the west. By late summer, the constellation returns to the northern region and takes a horizontal position. By utilizing the bucket shape of the Big Dipper, it is possible to accurately determine the local time. The internet provides various algorithms to solve this particular problem.

The United States of America

The Constellation Ursa Major

It appears that the Native Americans had an understanding of wild animals: according to the Iroquois legend about the origin of the asterism, the “celestial bear” is depicted without a tail. The three stars that form the handle of the Big Dipper represent three hunters who are chasing after the beast: Aliot is shown with a bow and arrow, Mitzar carries a cauldron for cooking meat (Alcor), and Benetnash carries a bundle of kindling to light the fire. During the autumn season, as the Big Dipper rotates and descends towards the horizon, blood from the wounded bear trickles down, staining the trees with a mixture of colors.

MAS

The Great Bear

The Big Dipper is a well-known group of stars that forms part of the third largest constellation in the night sky. Covering over 3% of the total sky area, the Big Dipper is not only home to various stars, but also hosts a number of distant and luminous galaxies. One of the notable galaxies in this region is the Vertushka galaxy (NGC 5457), which can be found to the northwest of Benetnash, the outermost star in the handle of the dipper. Recent studies have revealed that the five stars of the dipper’s bucket, excluding Dubhe and Benetnash, actually belong to a single star cluster known as Kolinder 285. These stars share a common origin and motion, with the cluster’s center located just 80 light-years away from the Sun. This makes Kolinder 285 the nearest star cluster to our solar system, and it is continuously approaching us at a speed of nearly 50 km/s.

The distinctive characteristic of the Great Bear Bucket is the presence of seven brilliant stars. In the past, scientists have identified between 24 to 35 celestial bodies within this constellation. However, the Yale catalog now lists over 200 objects within the Great Bear Bucket. It is possible to observe all of these objects without the need for any special optical equipment under certain conditions. Additionally, the Big Dipper also offers captivating sights such as luminous galaxies and nebulae.

Here are the seven stars that make up the Big Dipper:

– Dubhe, located at the top right of the Big Bear Bucket, is known as the “bear” in Arabic. It is the brightest star and is designated as the alpha of the constellation.

Bucket wall

The translation of Merak from below Dubhe means “lumbar”. When these two celestial bodies are seen together, they form the Bucket wall, also known as the pointer. Navigators and travelers use a straight line between them to locate Polaris in the tail of the Little Bear.

Mizar is the second brightest star in the tail of the Big Bear. It is also a double star, with a small companion called Alcor. In ancient times, people used the ability to distinguish this feature as a test of eyesight. The duo was also referred to as the horse and rider.

Aliot, the brightest star of the Ladle, is located closest to the bowl. The reason behind its nickname “curd” remains a mystery. Fekda got its name from the resemblance to a bear’s thigh. The stationary Benetnash is known as the leader of the mourners. Megretz, situated at the base of the constellation’s tail, is characterized by its faint luminescence.

Here’s an interesting fact: all the “members” of the Big Bear Bucket move together in a single stream, gradually spreading across the sky. This process occurs relatively quickly. However, there are 5 celestial bodies that move independently and shift synchronously in relation to the rest. This is what causes the visual changes in the image of the Bucket.

The Big Bucket represents just a small, yet incredibly impressive segment of this collection. When considering its overall size, this constellation is massive, ranking third in terms of area behind Hydra and Virgo. If we were to measure the space occupied by the asterism, it could fit around 4 thousand lunar disks.

Did you observe: Astronomical unit.

Almost everyone is familiar with the star Polaris. It can always be found in the same part of the sky and serves as a reliable guide for determining the north. By recognizing the appearance of Polaris or the positions of other constellations, you can navigate with confidence, even without the aid of a compass or other devices.

In this article, we will explore the fundamental methods for locating this prominent celestial object in the sky of the Northern Hemisphere. Our hope is that these strategies will enable you to accurately and effectively orient yourself in space.

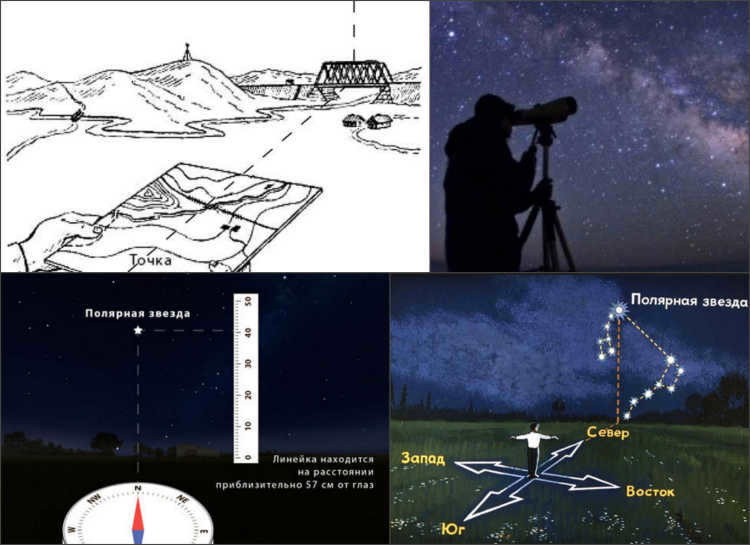

The position of the North is not solely determined by one reference point, but is also influenced by the positions of other constellations. However, using this method to navigate requires some understanding of astronomy. Additionally, there is a potential danger of misidentifying or mistaking a constellation, which could lead you in the wrong direction (Figure 1).

To avoid this situation, experts in orienteering still recommend locating Polaris in the night sky and utilizing it exclusively to determine your travel direction.

Thankfully, there is no requirement for maps or compasses to locate it. It stands as the most brilliant star in the sky and is positioned at the tail end of the Big Dipper. Additionally, while all other constellations gradually shift across the sky, this particular constellation remains stationary, serving as the central point.

Characteristics and Description of the Constellation

In order to effectively navigate in space, it is beneficial to acquire more knowledge about the appearance and qualities of Polaris, the brightest star in the sky (Figure 2).

It is common knowledge that Polaris outshines other celestial bodies. However, there are numerous other luminous objects in the night sky that can be perplexing to newcomers.

If one closely observes the night sky, it becomes apparent that all constellations are in gradual motion. This is due to the Earth’s rotation on its axis. Unlike the rest, Polaris remains nearly motionless. It is positioned at the center of the other constellations. It is because of this characteristic that the brightest celestial body always indicates north.

In order to determine the correct direction, you only need to follow a few simple steps. First, locate the Big Dipper in the night sky. Then, draw an imaginary vertical line from the Big Dipper to the visible horizon. The point where the line intersects the horizon will indicate the direction of North. South will be directly opposite the observer, while East will be to the right and West will be to the left.

Finding the North Star, Polaris, in the night sky is most easily accomplished by locating the constellation Ursa Major, also known as the Great Bear. While there are numerous visible celestial bodies in the sky, they will appear much brighter when viewed away from the glare of artificial city lights. The Ursa Major constellation is relatively simple to identify, as its star pattern resembling a dipper is visible year-round. Even novice stargazers should have no trouble spotting this group of stars (Figure 3).

At first glance, the Big Dipper appears to consist of only seven stars. In reality, there are many more stars that make up the constellation, but the brightest stars are the ones that give it the distinctive shape of a dipper.

In order to locate the bright spot, one must identify the two rightmost lights of the “bucket”. By connecting these lights with a horizontal line, you will come across a luminous point. This point stands out significantly in comparison to the surrounding smaller stars. This luminous point is actually a part of the Little Bear constellation. Its shape is reminiscent of a bucket, albeit much smaller in size and visually inverted in relation to the Big Dipper. Polaris is located at the end of the handle of the second bucket.

Incidentally, the positioning of the constellations is heavily influenced by the time of year. During the winter months, the Big Dipper appears to be on the “handle,” shifting towards the east. In spring, it is nearly at its highest point in the sky, while in summer it moves towards the center of the celestial dome. This is why novice stargazers often struggle to locate the primary constellation of the Northern Hemisphere during the warmer months.

Using a compass and a map to locate the north guiding star

Sometimes, the starry sky may not be fully visible due to obstacles like trees, hills, or clouds. In such cases, if it’s important to find Polaris, you can rely on a map and compass (Figure 4).

It’s important to note that the magnetic arrow of the compass generally points in the same direction as Polaris. However, adjustments need to be made for the magnetic pole and any distortion caused by magnetic lines. This adjustment is known as the magnetic declination of the area, and it can be found in a specialized reference book.

To locate the north guiding star using a compass, follow these steps:

- To find north and adjust for magnetic declination, use the compass. For instance, if the magnetic declination is 15 degrees west, you need to turn the compass arrow back to the left by the same number of degrees from the north end. This will indicate the direction of Polaris.

- When taking measurements, it is crucial to select an appropriate location. Avoid areas near power lines, vehicles, or railroads as they can interfere with the readings.

- To ensure accurate orientation, you must determine the elevation of the celestial body. This measurement is expressed in degrees and is approximately equal to the latitude of the terrain. This technique enables a more precise determination of the observer’s location coordinates.

All of these orienteering techniques are classified as extreme, and while they provide a fairly accurate way to determine direction, they are not entirely precise.

Finding Polaris in the sky by Cassiopeia

The easiest way to locate Polaris in the sky is by using the Big Dipper, but if you possess some knowledge in astronomy, you can also find it by referencing other constellations (Figure 5).

One more famous group, Cassiopeia, can assist you in locating the northern direction. It is situated on the opposite side of the “bucket”. In fact, Polaris is positioned between the Big Dipper and Cassiopeia, making it relatively easy to locate.

The search is conducted as follows:

- Draw a straight line visually through the two outermost points of the “bucket”.

- Perform similar actions with the celestial bodies on the opposite side of the constellation.

- Draw a line from the intersection of these two visual lines through the central part of Cassiopeia. Polaris will lie in this direction.

If you possess a keen eye, then locating the primary nocturnal celestial body of the Northern Hemisphere will prove to be effortless. Simply locate Cassiopeia and extend a line from its midpoint that is equivalent to two times the distance between the furthest points of the constellation. If executed accurately, you will undoubtedly be gazing at Polaris.

A great deal hinges on the specific geographical coordinates of the observation. For instance, during the summer months near the equator, the “Big Dipper” lies below the horizon and remains unseen to the average observer. Meanwhile, Cassiopeia and Polaris are visible, making it a breeze to locate them utilizing the aforementioned method.

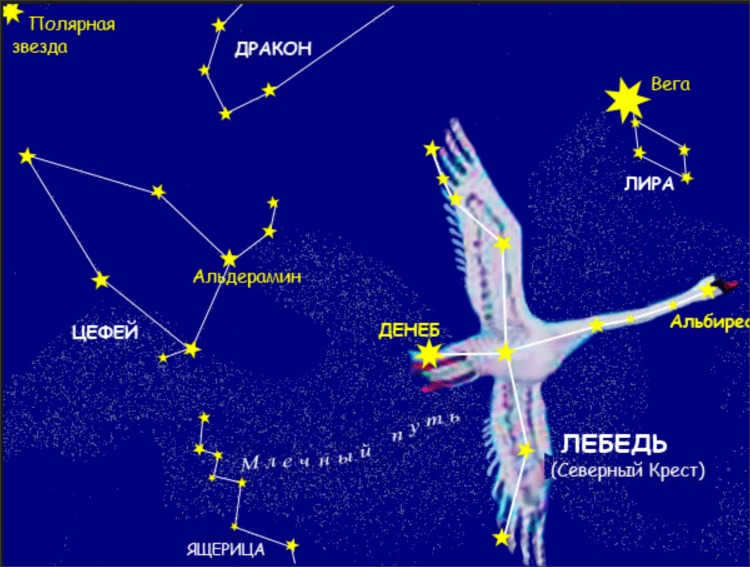

Guidance using the Swan constellation

Locating Polaris, also known as the North Star, by using the Swan constellation may not be a straightforward task, but it is highly effective. The main challenge lies in the fact that not everyone can easily spot the Swan in the night sky at first glance. However, with the proper knowledge of how to locate it, determining the northern direction becomes a simple task, even if certain parts of the sky and Polaris are obstructed by clouds (Figure 6).

In order to accomplish this, one must locate the two lowest points of the cluster: Hyena and Deneb. A visual straight line should be drawn between these two points. Starting from Deneb, a segment should be laid out that is equal in length to two distances between the lower luminaries. At the end of this line, the brightest point in the Northern Hemisphere can be found.

Looking for Orion’s Belt

Locating Polaris near Orion can be quite challenging, but with the right skills, it is definitely achievable. This technique comes in handy when part of the sky is covered by clouds, making it difficult to locate the North (Figure 7).

To accomplish this, you will not only need to identify Orion’s belt, but also its furthest point – Capella. Start by drawing an imaginary line through the center of the belt, specifically through the star Meissou. Extend this line towards Capella and beyond. Polaris will be located at the end of this visual line.