The emergence of practical cosmonautics occurred during a period of intense ideological and military-political confrontation between the USSR and the USA. The “Cold War,” which was officially declared by Winston Churchill in his renowned Fulton speech on March 5, 1946, fueled competition between the two nations across all aspects of life. It soon became clear that advancements in space exploration, which demanded the mobilization of a country’s intellectual and economic resources, would serve as a showcase for rivals, showcasing their capabilities to the world.

Origins

The concept of using rockets to explore space was initially proposed by scientists in the 19th century. However, progress in rocket technology was slow, and by the mid-20th century, rockets were primarily used as weapons. The German A-4 ballistic missile, also known as the “Fau-2”, was the most advanced rocket at the end of World War II. Originally designed as a retaliatory weapon, its innovative design and engineering principles became the foundation for the development of modern rockets. The technical advancements of the A-4 missile greatly influenced missile programs in the United States, the Soviet Union, Great Britain, and France.

In our nation, the advancement of long-distance missile weapons was focused in NII-88 (now – TsNIImash), established by the historic decree of the USSR Council of Ministers on May 13, 1946 “Reactive weapons issues. Design and development work on “ballistics” was carried out by Department No. 3 of NII-88 (since 1956 – OKB-1, now RKK Energia named after S.P. Korolev).

Under Korolev’s leadership, the first Soviet long-range ballistic missiles R-1 and R-2 were developed based on the A-4. The acquired experience allowed for the design of a completely original missile R-3 in the spring of 1947, capable of reaching targets within a radius of up to 3000 km: ten times further than the R-1 and five times further than the R-2.

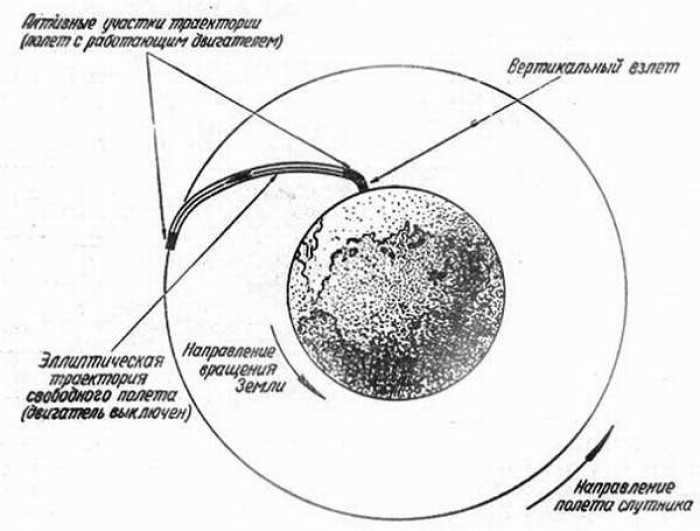

Around the same time, a team of specialists led by M.K. Tikhonravov at NII-4 (now TsNII-4 of the Ministry of Defense) published a report titled “Investigation of the Flight Ranges of Composite Liquid-Fueled Missiles without Wings”. This report presented the potential for creating and launching a man-made satellite by combining existing products into a “package”.

Korolev took an interest in the findings and commissioned further research from NII-4 and the V.A. Steklov Mathematical Institute of the Academy of Sciences (MIAN). In 1951, the conclusion was reached: a two-stage rocket using the package concept could not only achieve a range of over 8000 kilometers, but also successfully launch an artificial satellite. These findings laid the groundwork for the design of the first Soviet “intercontinental” rocket.

"Seven" and Sputnik

In February 13, 1953, a decree was signed by Stalin, which was called the "On the plan of research work on long-range missiles for 1953-1955" by the Council of Ministers of the USSR. This decree recognized the creation of intercontinental missiles as a task of special state importance.

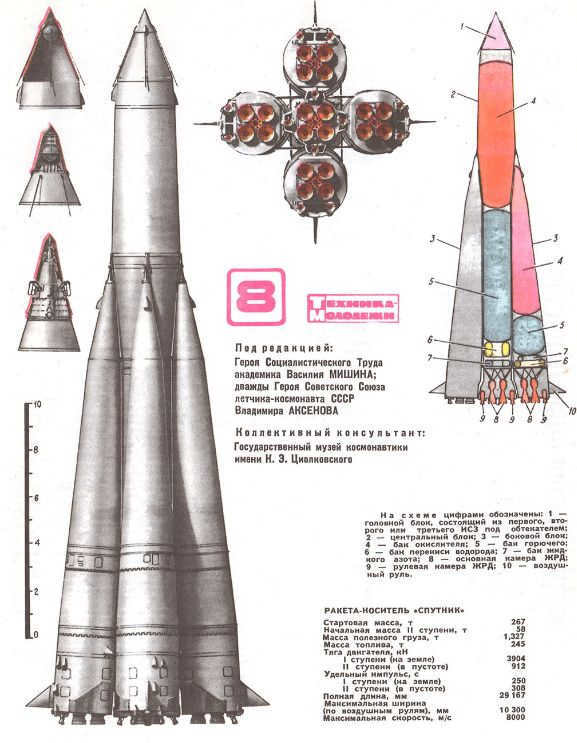

Korolev’s team dedicated their efforts to developing the R-7 product, which had a launch mass of approximately 170 tons. This product consisted of four side blocks and one central block, all powered by oxygen-kerosene engines developed by the Experimental Design Bureau-456 V. P. Glushko. At that time, the Seven was one of the largest aircraft in the world.

By the middle of 1953, when the initial design was nearly complete, the team working on the development of the thermonuclear charge, led by A.D. Sakharov, made a report stating that the weight of the nuclear warhead needed to be nearly doubled. In October 1953, the technical specifications for the rocket were revised: the launch weight increased by a hundred tons and the thrust of the engines had to be increased by one and a half times. These modifications had an impact on the project timeline, but not significantly. The updated “seven” was ready with its preliminary design by July 1954 and had already been approved by November.

The project’s success and the rapid development progress instilled confidence and opened up possibilities for launching satellites. In 1953, M.K. Tikhonravov’s team compiled albums detailing satellite work in the USA and the USSR’s capabilities in this field. These albums were presented to G.N. Pashkov, the head of the military department of Gosplan, who then presented them to Marshal A.M. Vasilevsky, the Minister of the Armed Forces. The Minister approved the work.

In December 1953, Korolev and Tikhonravov made the first attempt to propose the launch of civilian spacecraft. They suggested including a paragraph in the draft decree on the missile R-7 that stated: “Organize a research department in NII-88 with the task of developing issues related to the creation of an artificial Earth satellite and the exploration of interplanetary space…”.

Sergei Pavlovich put forward a plan in three stages to achieve a breakthrough in space exploration. The first stage involved the development of a scientific satellite weighing approximately one ton. Following this, the second stage would be the creation of a manned spacecraft capable of carrying one or two pilots. Finally, the third stage would involve the establishment of an orbital station. Ustinov expressed his support for this ambitious initiative.

By the middle of 1954, three key factors had converged, setting the stage for the subsequent success of the Soviet satellite project. Firstly, Korolev had gained the backing of both the military and political leadership of the country. They recognized that the creation of an artificial Earth satellite would have significant political implications, serving as tangible evidence of the nation’s advanced technological capabilities. Secondly, the resources and capabilities of the country enabled the development of both the necessary rocket and satellite. Lastly, the scientific community had reached a level of maturity where they were ready to embrace the idea of satellite exploration.

Satellite competition

Over in the United States, they quickly recognized the significance of the world’s first journey into space. “Just think of the shock and awe that would be felt if the United States suddenly discovered that another country, not them, had already successfully launched a satellite,” stated a report from the RAND Corporation, a strategic research center commissioned by the U.S. government and armed forces.

Above all else, the satellite launch demonstrated that the nation responsible possessed the technology to develop intercontinental ballistic missiles, a weapon that, according to politicians at the time, would finally resolve “all military matters.”

It is not surprising that work on satellites in the United States was already underway and quite active. However, this work was being carried out independently by various programs run by the Army, Navy, and Air Force.

One of these programs was the Vanguard project, led by the Naval Research Laboratory, which aimed to launch a small spacecraft using a specialized rocket. Meanwhile, Wernher von Braun’s team at the U.S. Army Ballistic Missile Agency proposed using a modified Redstone ballistic missile to launch the satellite. The developers were given one main condition by U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower: to ensure that their work did not interfere with the intercontinental ballistic missile program.

Preference was given to “Avangard”: primarily because of its low cost (estimated to be no more than $10 million), and secondly because the project was entirely American. The works of von Braun, a former Nazi, were considered “politically incorrect”. Additionally, it utilized a military missile, which contradicted the president’s ideals.

The initiation of the satellite race was triggered by the International Geophysical Year (IGY), announced in 1952 by the International Council of Scientific Unions: between July 1, 1957 and December 31, 1958, scientific endeavors related to the exploration of our planet were to be conducted. Among other things, participating nations were encouraged to launch the first man-made satellites into Earth’s orbit. And so, the race commenced!

On the 29th of July, 1955, the United States made an announcement about their plans to launch a “satellite” during the International Geophysical Year (IGY). Just four days later, L.I. Sedov, the head of our delegation at the VI International Astronautical Congress, revealed that the Soviet Union also had plans to launch satellites in the near future. Then, on the 5th of August, M.V. Khrunichev, the Deputy Chairman of the USSR Council of Ministers and Chairman of the Special Committee on Rocket and Jet Armament, gave instructions to create and launch an automatic artificial satellite called “Object D” before the Americans, using a modified R-7 rocket.

On September 11, 1956, in Barcelona, Academician I.P. Bardin officially confirmed that the Soviet Union had plans to launch a man-made satellite. Interestingly, this announcement was met with little enthusiasm: the Western world doubted our country’s ability to achieve a technological breakthrough within a short period of time.

Simultaneously, work was also progressing on the “seven” project: preparations for production began as early as 1955. By the spring of the following year, a prototype of the missile had been assembled, and by the summer, bench tests of the side and center blocks were being conducted at Novostroika (now the Research and Development Center of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Peresvet). The culmination came in the first quarter of 1957 with the successful firing of two R-7 “packages,” which allowed for the commencement of flight tests.

The initial launch of the R-7 occurred on May 15, 1957. The rocket departed the launch site smoothly and flew without any issues for approximately one hundred seconds. However, an incident took place when a fire broke out in the rear of one of the “sidearms”.

The attempt to launch the rocket on June 10-11 was unsuccessful as the engines did not generate the necessary thrust, preventing the rocket from lifting off. In the second launch on July 12, an emergency situation arose as the product started to spin uncontrollably.

Finally, on August 21, 1957, the “seven” successfully completed its first full active section operation. Radars tracked the flight until re-entry into the atmosphere. Although the head section was destroyed, the most important achievement had been accomplished: the Soviet Union became the first country in the world to develop an intercontinental ballistic missile!

On September 7, the second successful launch of the R-7 occurred. The entire trajectory was completed, but unfortunately, the head section was once again destroyed.

From Obiekt D to the Simplest Satellite

Progress on Obiekt D, which was intended to become the First Sputnik, and its carrier was well underway. However, in the second half of 1956, there was a delay. The world’s first space laboratory proved to be too complex, and much of the scientific equipment had to be manufactured for the first time. To make matters worse, the development of an upgraded version of the R-7 was falling behind. As a result, the potential launch of Object D was postponed until April 1958, potentially causing the Soviet Union to lose its chance at space supremacy.

In a letter dated January 5, 1957, S.P. Korolev suggested to D.F. Ustinov that priority launches of basic satellites be carried out using one or two R-7 rockets from the flight testing program. He justified his proposal by stating the importance of not falling behind in the space race: “Based on information from various sources, it seems that the United States is planning to make further attempts to launch an artificial satellite in the near future, presumably with the aim of achieving priority at all costs.”

The suggestion received approval, and a decision from the Presidium of the CPSU Central Committee and the USSR Council of Ministers authorized the execution of the Object PS project. The plan was to send two simplified satellites into space, “but only after achieving successful outcomes from the launch of one or two [military] R-7 products”. As previously stated, this requirement was met in September 1957. Thus, the path to launching the first-ever man-made satellite was now clear.

Originally, the launch was planned for October 6th. However, shortly before that, there was news that the US representatives at the meeting discussing rocket and satellite launches as part of the IGY were preparing a report titled “Satellite over the planet.” This raised suspicion that the Americans were planning a launch on the same day as the report. S.P. Korolev took a risky decision without consulting the country’s leadership: to launch the satellite two days earlier.

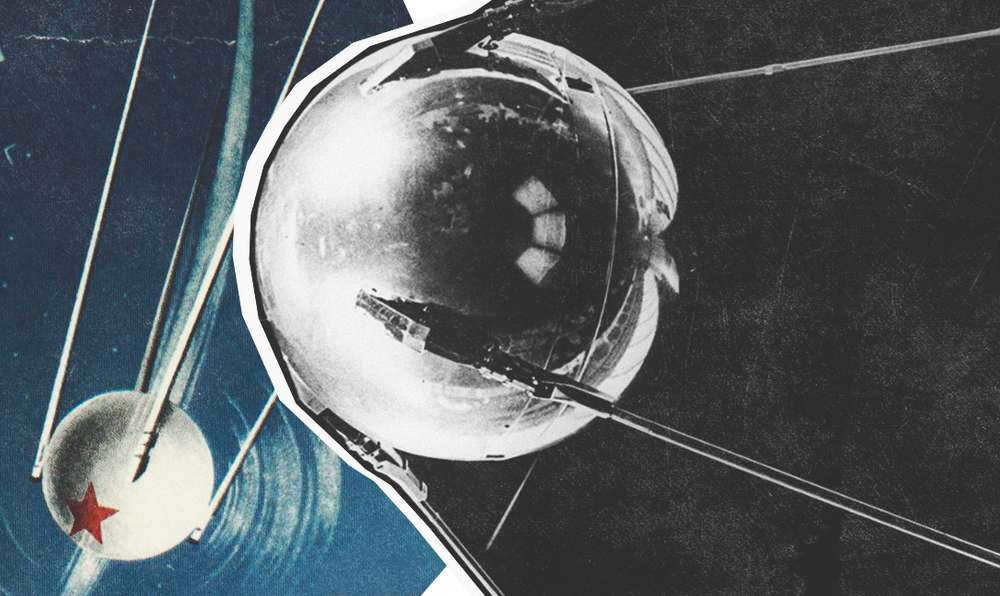

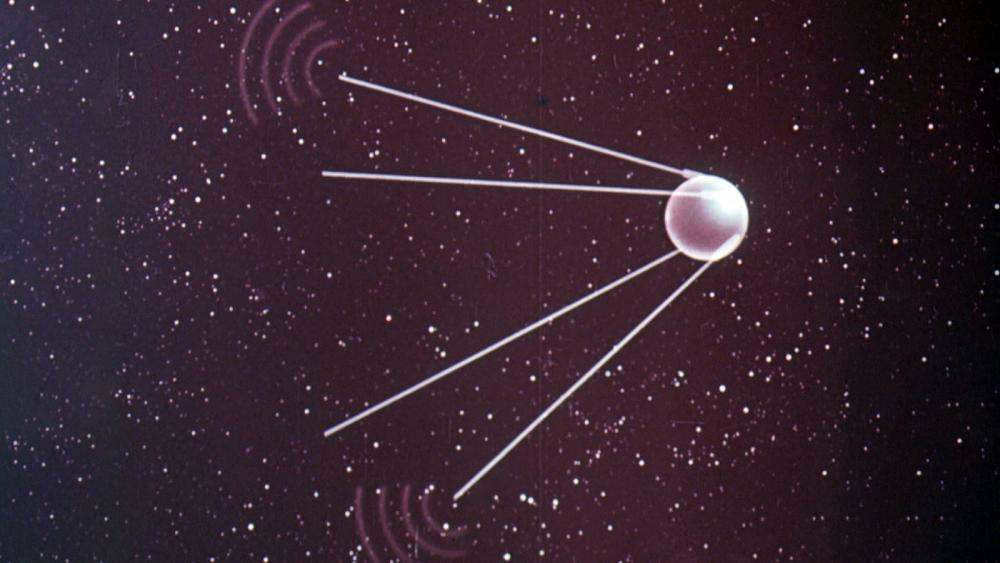

On October 4, 1957, at 22:28:34 Moscow time, the “seven” was launched, marking the first time in human history that a satellite was placed in orbit. With its “beep-beep” sound, it signaled the beginning of a new era – the Space Era!

As for the United States, they didn’t launch their first satellite until four months later, on February 1, 1958.

We are currently living in an era of space exploration, and it has become such a common occurrence that we often overlook the significance of important events. Not everyone can accurately recall the exact date when the first artificial satellite was launched, even though it occurred relatively recently, just a few decades ago. This momentous occasion took place on October 4, 1957. Since then, numerous reusable rockets and orbital stations have been successfully launched. In this article, we will delve into the origins of space exploration, share fascinating historical facts, discuss the program’s significance, and explore the scientific discoveries that have resulted from this remarkable event.

Overview

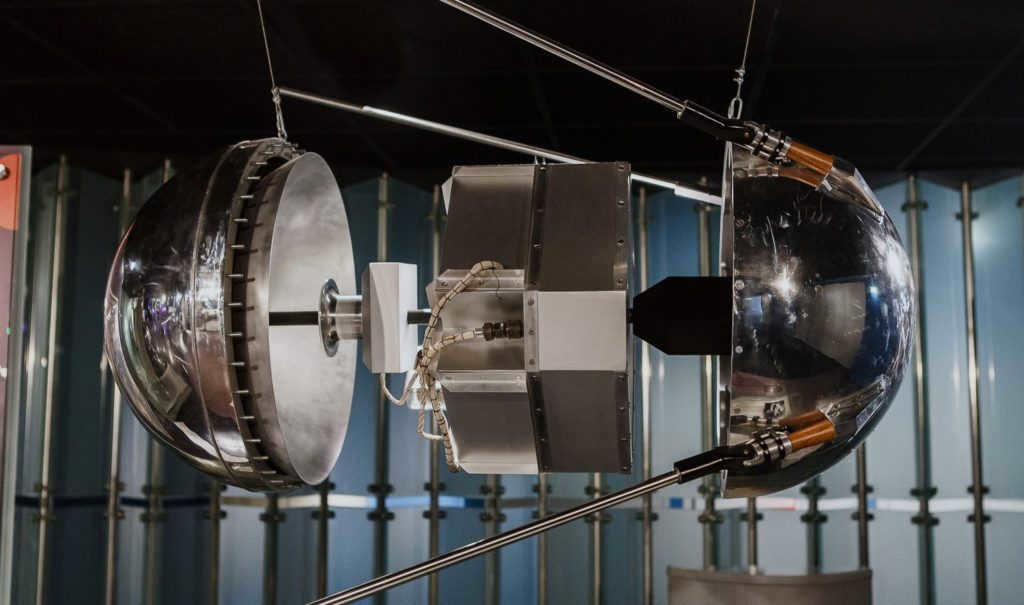

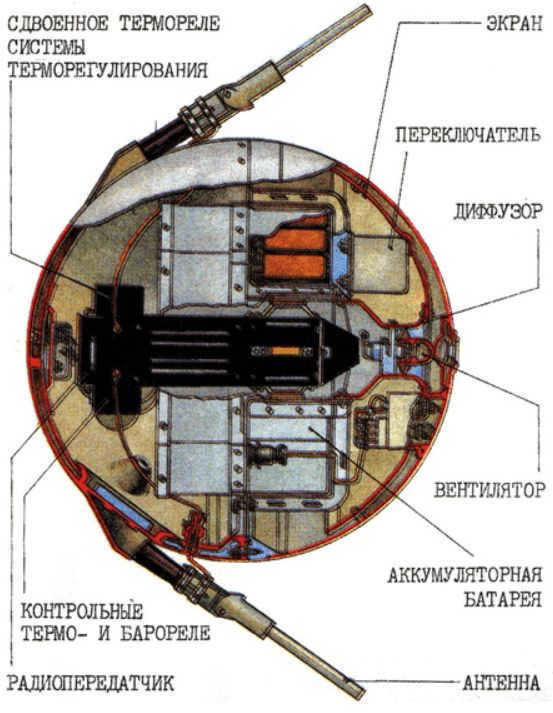

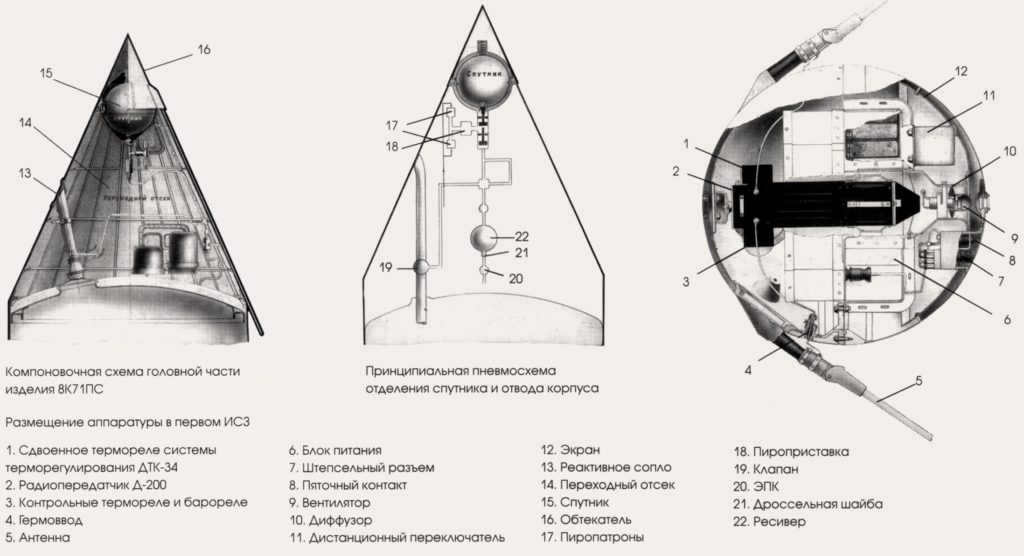

The initial satellite had a basic appearance, consisting of a 60 cm aluminum sphere with two curved antennas attached to it. The crossed antennas served the purpose of evenly transmitting radio waves in all directions. The sphere was constructed by joining two halves with bolts. Internally, it contained various components such as batteries weighing up to 50 kilograms, a thermostat, a cooling fan, heat and pressure sensors, and a radio transmitter that was prepared to transmit signals back to Earth. Overall, the structure weighed slightly over 80 kg.

The first Earth satellite was widely known by Soviet schoolchildren at the time. However, it is not as well-remembered by current adults that its official name was “Prostrashchiy Sputnik-1,” also known as PS-1. Interestingly, it transmitted signals on frequencies that could be easily intercepted and listened to by radio enthusiasts.

Creation process

An important achievement in the history of space exploration was the development of the Faou-2 ballistic missile by Werner von Braun, a German designer. In 1942, a test launch was conducted, followed by a real launch two years later. A total of 3225 launches were carried out, with the majority taking place in Great Britain. Following World War II, von Braun surrendered to US forces and subsequently became the head of the Armament Development Service.

In the same year, Stalin issued a decree expressing the necessity of establishing a missile facility within the Soviet Union and appointed Sergei Korolev as the primary architect of ballistic missiles. The ensuing decade was dedicated to the advancement of these missiles. In 1948, designer Mikhail Tikhonravov delivered a presentation to scientists regarding composite missiles. He provided calculations that indicated rockets weighing a ton had the capability to traverse vast distances and even hypothetically launch the first Soviet satellite into orbit around the Earth. The speech faced criticism and even ridicule, leading to the dissolution of the speaker’s department due to the perceived irrelevance of the proposed solutions. The department’s operations were only reinstated in 1950, at which point Tikhonravov began to assert the possibility of launching a satellite more directly and emphatically.

About the advancements

In 1953, scientists and engineers were successful in persuading the leaders of the country that launching a satellite into space was a real possibility. The support of the top military officials played a significant role in promoting the idea and assessing its potential. The next year, a decree was issued to establish a working group led by Tikhonravov. In a short period of time, the team developed a comprehensive space exploration program, which included plans for launching an ISV and even landing on the moon.

The procedure of the launch

The approval for the establishment of a scientific research test site number 5, which was later named Baikonur, was granted in 1955. The location chosen for this site was the Kazakhstani desert. It was here that the first R-7 rockets were launched. However, it soon became evident that the head part of the rockets needed improvement, as it was too large and could not withstand temperature tests.

In 1957, a lighter version of the R-7 rocket was developed, weighing seven tons less. Korolev, the chief designer, had planned flight tests for October of that year. Despite receiving no response from government officials, Korolev made the bold decision to proceed with the launch of the rocket carrying a satellite. This historic event took place on October 4, coinciding with the opening day of the VIII International Congress of Astronautics in Barcelona. The Soviet Union had kept its work on the first Earth satellite a secret from the world, but it was finally revealed at the congress, causing a sensation. During the congress, mathematician and physicist Leonid Sedov delivered a speech that earned him the title “the father of the satellite.”

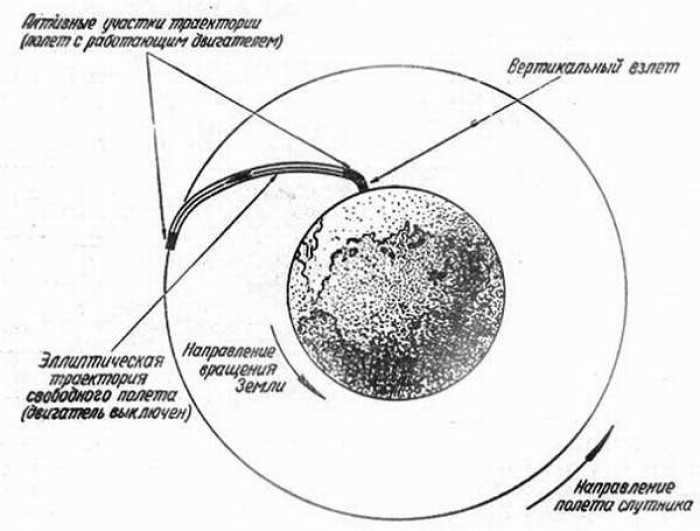

The launch occurred from the initial Baikonur site, known as NIIP No. 5 at that time. After 295 seconds, the spacecraft was propelled into a elliptical orbit around the planet, and 20 seconds later, the PS separated from the R-7 and transmitted a signal back to Earth. The test site received the repeated signals for a duration of two minutes, after which the satellite moved beyond the horizon and the radio signal was lost. PS-1 had just completed its inaugural orbit around the planet when TASS announced the successful launch.

However, subsequent data suggested that the initial reports may have been premature. It appears that the spacecraft failed to achieve Earth’s orbit due to insufficient velocity. It seems that it struggled to attain the necessary speed to enter into the first stage of space travel. The malfunction was attributed to a problem with the fuel management system, resulting in one of the engines operating at a slower rate than intended.

Nevertheless, the launch can still be considered a success. The spacecraft successfully entered into an elliptical orbit and completed 1,440 revolutions around the planet along this path. This journey took a total of 92 days, with the radio transmitters operating effectively for the first two weeks. Naturally, one may wonder what occurred afterwards and the current whereabouts of the first Earth satellite.

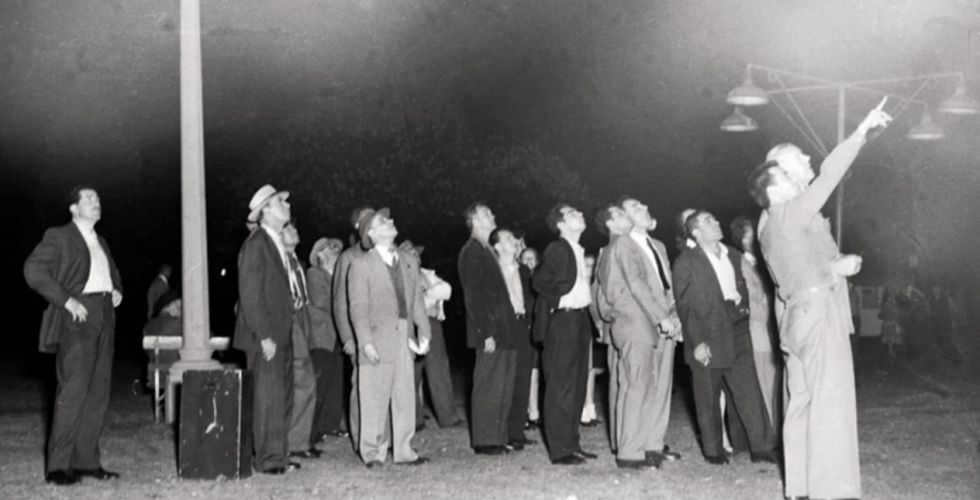

PS-1 met its demise under well-documented circumstances. It experienced a decrease in velocity as a result of atmospheric friction, leading to its descent and eventual complete incineration upon entering denser layers. This incident was witnessed by individuals who observed a gleaming object traversing the sky. However, this object was not the first satellite to emit such glimmers, as it would have been imperceptible without the aid of specialized optics. In truth, it was the second stage of the R-7 rocket, which, as per the intended plan, separated from the main rocket and entered orbit alongside the satellite.

The importance of flying

The project’s implementation became a globally significant event, tarnishing the reputation of the United States. The Soviet Union emerged as the undeniable frontrunner in the race for space, instilling a tremendous sense of pride among its citizens. When discussions arose within the international community regarding the potential launch of the world’s first artificial satellite, the USA was consistently mentioned, while the USSR actually achieved it.

Perceptions of Soviet technological backwardness were swiftly debunked on a global scale. This fact was widely known, as even amateur radio operators could intercept signals from the IS. This marked the dawn of a new era in space exploration, where the superpower rivalry played out through actions rather than mere words. And it was the Soviet Union that took the first leap forward.

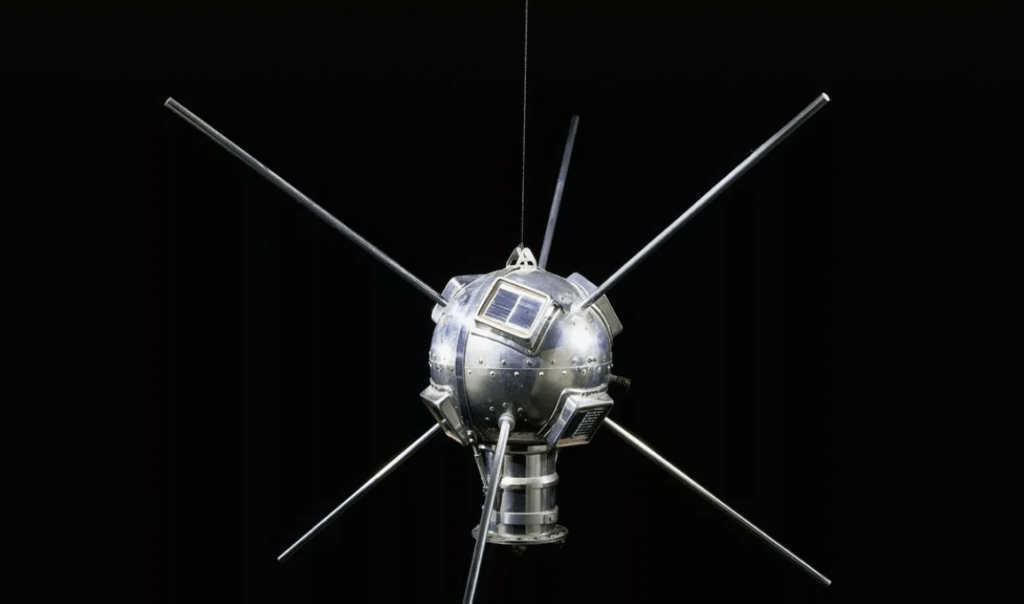

Regarding the United States, they managed to launch their initial satellite merely four months later, which they named “Explorer-1”. The creators of this satellite were experts from Wernher von Braun’s team. In terms of weight, the American model was significantly lighter than the Soviet one, as it only weighed 4.5 kg. To put it into perspective, the weight of the IS-1 battery alone was over ten times greater. Nevertheless, this achievement did not represent a groundbreaking moment, as the US was not the first country to take this significant leap forward.

Scientific Achievements

The project had a number of scientific objectives:

- Verifying the capabilities of the apparatus and the accuracy of the calculations made for its launch;

- Investigating the ionosphere, which had previously been inaccessible for study as all radio waves sent from the Earth’s surface were reflected by this layer. The satellite allowed for the transmission of waves from space;

- Determining the density of the upper layers of the atmosphere. Scientists observed the deceleration of the device due to friction against the atmosphere and conducted calculations;

- Examining the behavior of equipment in outer space and assessing the degree of favorable conditions present.

Although the number of objectives was limited, their accomplishment represented a major milestone, particularly considering the absence of any scientific instruments on the satellite. The density of the atmosphere was discovered to be surprisingly high, and this discovery provided a crucial foundation for the theory of satellite deceleration. This contribution is of great significance to the advancement of space exploration.

Engaging Information

- In Moscow stands a monument dedicated to the individuals who were instrumental in creating the world’s first man-made satellite.

- The magazine “Radio” used to contain instructions for radio enthusiasts on how to pick up signals from outer space. The PS-1 signal was accessible to anyone.

- In those days, scientists would spend around 30 seconds to a minute to determine the coordinates of a location using a time reference. Nowadays, a computer can do it in a matter of seconds.

- Prior to the launch of the American satellite, Soyuz successfully launched a second vehicle into orbit, carrying an animal on board for the first time. A dog named Laika was intended to spend about a week in orbit, but unfortunately, she couldn’t withstand the heat and passed away within hours.

- The commencement of the space race prompted the United States to establish NASA.

- The occurrence had a significant impact on the development of the internet. It paved the way for a potential new broadcasting network, prompting the United States to establish its own long-distance transmission system. Efforts were made to create a network between computers, resulting in the establishment of the ARPANET network, which initially connected a research center and three universities. Over time, technological advancements led to the emergence of the World Wide Web.

Now you have a clear understanding of when the first artificial satellite was launched, who was leading the project, and what makes it remarkable. The exploration of space continues, and you can explore the most unusual known celestial objects by reading the article “5 Strangest Objects in Space”.

The successful launch of the First Sputnik sparked strong responses worldwide – from jubilation among the “victors” to despair among the “losers”. Even after it was revealed that the satellite — was a simple aluminum sphere with antennas, posing no threat, the unease did not dissipate. Instead, it was met with a strong desire to achieve parity with the USSR in the realm of rocket and space technology.

The information regarding the upcoming launch of an artificial satellite was spread through the Soviet media beforehand, but the specifics were kept hidden, causing the global community to react to the news of a new miniature “moon” appearing in the sky with some delay.

A brief report about the launch was released by TASS on October 5th, and the following day, the main Soviet newspapers published more detailed information. Simultaneously, feedback from foreign sources also started pouring in.

Among the first to comment was British astronomer Bernard Lovell, who is the founder and director of the Jodrell Bank Experimental Radio Telescope Station. He expressed that the launch “represents a remarkable accomplishment and demonstrates a significant level of technological advancement.” His sentiments were echoed by Joseph Kaplan, the chairman of the U.S. National Committee for the International Geophysical Year, who said, “I am astounded by what they have been able to achieve within such a short timeframe. This is truly extraordinary, and if they can successfully launch a satellite like this, they can certainly launch even heavier ones in the future.”

The Italian newspaper Paese Sera has summarized that Soviet scientists are ushering in a new era of boldness and advancement for mankind. The successful launch of an artificial satellite is the pinnacle achievement in humanity’s century-long quest to overcome the forces of nature. The Soviet people have accomplished this feat, and the whole world is indebted to them for it. October 4th will forever be etched in the annals of history as a momentous day.

A completely different atmosphere prevailed in the United States, where citizens suddenly grasped the magnitude of what was happening as a “defeat”. The acknowledgment of the renowned author Stephen King, often referred to as the “king” of the horror genre, became a defining moment. He later recounted that it was the news of the First Sputnik that instilled in him the greatest fear as a child: “The first time I experienced terror – true terror, not a confrontation with demons or ghosts living in my imagination – was on an October day in 1957. <. >I had just turned ten. And, fittingly, I was in a movie theater. <. >The manager stepped onto the stage and raised his hand, signaling for silence. <. >He appeared worried and frail – or perhaps it was just the lighting. We wondered what catastrophe had compelled him to halt the film at its most intense moment, but then the manager spoke, and the tremor in his voice left us even more bewildered. “I want to inform you,” he began, “that the Russians have successfully launched a satellite into orbit around the Earth. They have named it Sputnik.” <. >I remember vividly: the dreadful silence of the cinema hall was abruptly shattered by a solitary cry; I couldn’t discern whether it came from a boy or a girl, but the voice was filled with tears and terrified anger: “Come on, show the movie, liar!” The manager didn’t even glance in the direction from which the voice emanated, and somehow that was the most agonizing part. This was the evidence. The Russians had surpassed us in space.”

However, not only American children were frightened by the news, but also the highest political leadership, the command of the Armed Forces, and even analysts from the Central Intelligence Agency.

“Threat” from the Satellite

In August 1957, the CIA discovered the location of the testing site for the Soviet R-7 intercontinental ballistic missile near the Tyura-Tam railroad station in Kazakhstan. This information was obtained after a U-2 reconnaissance plane captured photographs from high altitudes. At that time, the only operational launch complex was located at the range, leading to the comforting conclusion that a single missile could not pose a significant threat to the United States and its allies.

In October 1957, attitudes began to shift. The launch of the First Sputnik ignited a change in the Western press, as they began to promote the notion of Soviet missile superiority over American missiles. They pointed to the regular flights of the 84-kilogram balloon above our heads as clear evidence. Headlines appeared, such as “Senator Russell Asserts Satellite’s Military Importance,” “Military Implications of the Red Moon,” “An Unavoidable Challenge,” “Presidential Candidate Edlai Stevenson Highlights U.S. Security at Risk,” “Hysterical Response to Satellite,” “U.S. Bewildered by Red Satellite,” “Satellite Sends Shockwaves Across the World,” and more.

The media also revealed that a team of rocket scientists from the Redstone Arsenal had been prepared to launch a satellite six months ago. However, the contract was ultimately awarded to the Navy, who failed to successfully complete the mission. This situation was on the brink of causing a major scandal.

As a result, President Eisenhower was compelled to address the issue at a press conference on October 8th. He stated, “The Soviet satellite currently orbiting the Earth does not pose a threat to American security.” The President attempted to justify the United States’ lagging progress in comparison to the USSR by explaining that the satellite program was always intended to be separate from military ballistic missile development. He emphasized, “Our satellite program was never intended to be a competition with other countries. Instead, it was meticulously planned as part of a scientific endeavor during the International Geophysical Year.”

Furthermore, the president informed the gathered journalists that the inaugural American satellite would be sent into orbit in December.

Eisenhower’s remarks provided little solace to the general public, as the Soviet satellite persisted in circumnavigating the globe and transmitting distinct signals. To make matters worse, due to a disclosure in the Trud newspaper, the Western media became aware that the Russians were getting ready to launch a satellite of even greater sophistication on the 40th commemoration of the Great October Revolution, specifically in early November.

On October 7, the Soviet Union made a public declaration about the existence of two objects circling the Earth: a balloon-shaped satellite, measuring 58 centimeters in diameter, equipped with radio antennas, and a large launch vehicle stage. However, for some reason, Western commentators chose to overlook this information. To their surprise, on November 3, the Second Artificial Earth Satellite was launched with the inclusion of the dog Laika. The stated weight of the spacecraft, 508.3 kg, did not account for the mass of the empty second stage, which weighed over 7 tons and was intentionally not separated from the satellite. Nevertheless, experts and journalists were generous in their praise for the Soviet scientists, hailing this new achievement as “astonishing.” However, this development posed yet another problem for the White House.

Once again, Eisenhower faced criticism and calls for action to address the gap between the United States and the Soviet Union. Democratic Senator Frank Church pointed out that the Soviets were lagging behind in the development of the atomic bomb by four years and the hydrogen bomb by one year. Furthermore, the Soviets had surpassed the United States in creating intercontinental ballistic missiles and launching the first man-made satellites. This marked a significant victory for the Soviets in the ongoing psychological warfare between Communist and free governments. Church argued that a new Manhattan Project was needed to restore America’s and the free world’s dominance in outer space and scientific advancements.

When the Vanguard TV-3 rocket, which was carrying a small satellite weighing only 1.36 kg, exploded at the launch pad on December 6, all of his promises were exaggerated.

The frenzy surrounding the missile

The perceived failure solidified the belief within Western society that the United States was not only falling behind in space exploration, but also in the advancement of strategic missiles. One of the most vocal advocates for an immediate resolution to this problem was influential journalist Stuart Elsop. In an emotionally charged article published in the Saturday Evening Post on December 14, Elsop stated, “It is undeniable that strategic missiles will soon render heavy bombers obsolete, just as firearms have rendered knightly armor and swords unnecessary. We are facing the threat that the Soviets will make this transition before we do. In other words, they will achieve a breakthrough – as the Pentagon puts it – and we will find ourselves in a situation similar to the French knights at the Battle of Crécy, armed with swords and vulnerable to the accurate arrows of skilled British archers.”

The analysts who had access to current classified information knew that the USSR had a single launch complex at Tyura-Tam, which was used for launching both intercontinental missiles and satellites. The mood of these analysts was also influenced by the prevailing atmosphere, unlike Elsop. Their evaluation of the future shifted, as evidenced by the report “The Soviet ICBM Program,” compiled by the Office of Scientific Intelligence staff in late 1957.

According to the report, the USSR has stated that the development of ICBMs is its top priority. It is expected that the USSR will make every effort to enhance its strategic ICBM capabilities to the maximum extent possible. In the period from mid-1958 to mid-1959, it is likely that the USSR will establish its first operational center for working with ICBM prototypes that closely resemble actual combat models. The Soviets have the capacity to produce ICBMs, construct launchers, and train personnel at a pace that would allow them to manufacture 100 ICBMs within a year after the first operations center is established, and 500 ICBMs within two or, at most, three years after the establishment of the first operations center.

Undoubtedly, these approximations were greatly exaggerated: the Soviet strategic missile forces were still in their early stages, and by the conclusion of 1961, only four launch complexes for R-7A missiles, including the “satellite” one, had been constructed.

President Eisenhower received highly detailed information regarding this construction through various intelligence channels, but chose not to publicly dispute the claims of the USSR’s overwhelming superiority in missiles, out of concern for revealing the sources of information. This “weakness” was exploited by his primary political opponent, Democratic Senator John F. Kennedy, who asserted that “the country is falling behind in the rocket-satellite race with the Soviet Union due to satellite miscalculations, greed, budget cuts, incredibly convoluted mismanagement, wasteful competition, and envy.”

In July 1960, during Kennedy’s presidential campaign, Eisenhower organized a meeting between him and Allen Dulles, the CIA director, to address the growing concerns about missiles. Dulles assured Kennedy that the rumors of Soviet missile superiority were greatly exaggerated. Despite this reassurance, Kennedy chose to maintain his stance, seemingly convinced that emphasizing the “missile-satellite gap” would be a compelling argument in the election debates.

The commencement of the “competition”

Despite President Eisenhower’s reluctance to acknowledge the rivalry in space endeavors between the United States and the Soviet Union, the prevailing perception in Western society was that a “competition” was underway: rockets, the moon, and space.

To address the delay in satellite launches, Defense Secretary Neil McElroy, on November 8, 1957, directed the involvement of the U.S. Army Ballistic Missile Agency in the project. Their objective was to expeditiously develop their own spacecraft launch capability using a Jupiter-C rocket constructed by Wernher von Braun’s team.

As events unfolded, it became clear that the decision was correct: during the night of January 31 to February 1, the Explorer satellite weighing 13.9 kg (including the empty fourth stage of the rocket, which weighed 8.3 kg with the equipment container) was successfully launched. Commentators breathed a sigh of relief, stating that the United States had finally joined the “race” and had a chance to take the lead.

Everyone involved understood that the next significant historical achievement, which would solidify the dominance of one of the competing countries, would be the manned spacecraft flight. Since the end of 1957, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) had been exploring the establishment of a new civilian agency that would coordinate various ambitious projects related to satellite constellations and spacecraft design.

President Eisenhower deemed the suggestion to be fair and reasonable, and on April 2, he proposed to Congress the creation of a civilian agency to oversee all space activities unrelated to the military. Congress reacted by passing legislation, which Eisenhower enacted into law on July 29. Consequently, NACA transformed into the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

On October 1, the agency commenced operations, and a week later, they officially approved the project for a manned spacecraft called Astronaut, which was later renamed Mercury. It can be said that this marked the beginning of a genuine space “race”.

Outer space

During its existence, the Soviet Union actively pursued humorous initiatives aimed at the exploration of outer space. The first milestone in this endeavor was the launch of a satellite – the very first object to be sent into outer space. This momentous event marked the commencement of further expeditions into the vast universe. Nevertheless, it is not widely known that this remarkable contraption has quite a fascinating backstory.

Overview

In the latter part of the 20th century, the Soviet Union and the United States engaged in a competitive race to establish dominance in space exploration. The Soviet Union achieved a significant milestone by successfully launching their own spacecraft into Earth’s orbit. This groundbreaking device was aptly named “Sputnik-1”.

Fascinating tidbit: Interestingly, the spacecraft was referred to as PS-1 in official documents and technical drawings, which stands for “Simplest Sputnik-1”.

The apparatus was designed with simplicity in mind. Its structure consisted of a sphere with antennas positioned on its sides. These antennas were essential for evenly distributing the satellite’s radio signal into space.

To assemble the sphere, two hemispheres were joined together using a total of 36 bolts. This ensured a secure and gap-free connection between the parts. Inside the PS-1, various components were present, including temperature and pressure sensors, silver and zinc batteries, a thermostat, a radio transmitter, and a cooling fan for the elements.

While in orbit, the First Sputnik emitted a signal with a frequency range of 20 to 40 MHz, allowing anyone, including ordinary people, to tune in to the device’s broadcast.

Although nowadays when discussing space travel, we often think of large rockets and shuttles, the Sputnik-1 was actually quite small compared to a human. It had a radius of only 29 cm and weighed approximately 83.5 kg.

The prototypes of Sputnik

Back in 1687, while penning his masterpiece “Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy,” Sir Isaac Newton speculated about the possibility of launching a celestial body into Earth’s orbit without it succumbing to gravitational pull and plummeting to the surface.

To achieve this outcome, the scientist proposed the following experiment. The initial step involves ascending a tall mountain, whose peak surpasses the atmosphere by a significant margin. From this vantage point, it is necessary to fire a cannon in such a manner that the projectile will travel parallel to the ground. If the projectile is launched at a specific velocity, it will remain in perpetual orbit around the planet, never descending to the surface.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, there was a growing belief that technological advancements would soon enable space travel. Tsiolkovsky, a scientist of the time, even suggested that mankind was prepared for interstellar journeys. He went a step further by proposing the construction of a rocket capable of carrying human passengers, rather than relying solely on experimental launches. This groundbreaking approach would provide valuable firsthand accounts from the very first flight, ensuring the authenticity of the information obtained.

Subsequently, a proposal was presented by German engineer Oberth for a multi-stage station to be launched into orbit. The purpose of this station was to observe and coordinate military forces. The proposal included the installation of a telescope on the extraterrestrial object, allowing for direct observation of planets and stars from space, free from atmospheric distortions.

Furthermore, the concept of satellites was explored in various science fiction novels published during the 1920s and 1930s. Throughout the first half of the 20th century, numerous countries conducted experiments in an attempt to launch objects into Earth’s orbit. However, the rockets developed at that time did not achieve sufficient speed.

Fascinating trivia: In 1944, the military officer Pokrovsky came up with the idea of launching projectiles into the sky using a formidable cannon. His belief was that this would result in the remnants of the projectiles entering orbit.

Initial endeavors

The scientists of Nazi Germany successfully developed the Fau-2 rockets, which were powered by liquid fuel and had a large mass. These rockets were believed to have the capability to reach outer space and even put a human into orbit. Official documents suggest that there were plans to use these rockets to launch embalmed bodies of the first space travelers as a way to honor them.

Starting from March 1946, the United States Air Force actively began working on their own space program. The country recognized the importance of placing objects in Earth’s orbit to gather valuable information and enhance their credibility among other nations.

Computer model of the American rocket “Redstone”

In 1954, a gathering of prominent American rocket engineers took place to deliberate on the likelihood of launching a satellite within the next three years. It became evident that achieving this goal would necessitate the utilization of multi-stage rockets, where the preceding stages would detach and trigger the subsequent ones to propel the rocket to the desired altitude.

Fascinating triviaThe United States possessed Loki and Redstone rockets in its arsenal during that period, which were intended for the inaugural satellite launch.

The meeting resulted in the creation of the Orbiter project, which focused on finalizing the specifics of a forthcoming space launch. The anticipated date for the event was set for the summer of 1957. Two years prior to this, in 1955, the United States made the project public, subsequently renaming it as “Vanguard”. The intention was for this satellite to be launched into the sky using the Viking and Aerobee rockets. On paper, the device was described as a sophisticated structure weighing 10 kg. The plan was to equip the device with a multitude of electronics in order to gather data.

However, once news of the Soviet space program became public, the United States made significant simplifications to the design of their satellite in order to be the first to launch an object into space. As a result, Avangard-1 lost six times its original weight, resulting in a mass of 1.59 kg.

The History of the First Artificial Satellite

The development of the satellite began in 1942, when German designer von Braun completed the modeling of the Fau-2 missiles. Several months later, the first launch occurred, and by 1945, a total of 3225 tests had been conducted. It became evident that this missile had the capability to travel long distances.

Following World War II, von Braun joined the U.S. Department of Defense and was involved in the advancement of rocket technology to launch the first satellite into Earth’s orbit. The plan was to develop a device within a five-year timeframe that would enable this achievement. However, the government later withdrew funding for the project.

In 1946, the rocket industry of the USSR was established by Stalin, with Sergei Korolev being assigned as its head. By the early 1950s, the Soviet Union had already made significant progress in missile development, with the creation of the R-1, R-2, and R-3 missiles. These missiles had the capability to travel long distances and strike targets on nearby continents. In 1948, designer Tikhonravov presented staged rockets that had the potential to reach distances of over 1000 kilometers. He suggested using these rockets to launch satellites into Earth’s orbit. However, his proposal did not receive support and he was removed from the project. Two years later, with the recognition of the importance of space exploration, Tikhonravov was reinstated and tasked with developing technologies to successfully launch a satellite into orbit.

Model

The creation of the R-3 rocket and its capabilities made it evident that it had the potential to be utilized in launching the initial satellite into orbit. In 1953, the architects involved in this project ultimately succeeded in persuading the government that sending an artificial object into space was feasible.

In 1954, Tikhonravov and his colleagues embarked on a comprehensive examination of the USSR’s space program, the initial phase of which was centered around launching a satellite into orbit.

Fascinating fact: Additionally, Tikhonravov was entrusted with the task of devising a potential manned mission to the Moon, which was slated to occur subsequent to successful space voyages.

In 1955, Khrushchev personally visited the factory where the R-7 rocket was being manufactured. As a result of his visit, a decree was signed by the designers to construct a device capable of circling the Earth.

In November 1956, the construction of the first satellite commenced, and just 10 months later, the completed model was undergoing testing under special conditions. Based on the results of the experiments, it was evident that the device was prepared for launch.

Satellite’s Device

As mentioned earlier, the satellite consisted of two halves, which were made of an aluminum and magnesium alloy with a 2 mm thickness. The halves were connected using M8*2.5 bolts. Inside the structure, nitrogen gas was filled to create a pressure of 1.3 atmospheres. To prevent air leakage, rubber lining was placed at the joints. Additionally, the satellite was equipped with a thick outer shield to maintain a constant temperature.

Fascinating fact: The satellite’s surface was polished and treated to give it its optical properties, resulting in its shiny appearance.

To send the signal, we installed two antennas in the front half of the device. One antenna was a VHF type, while the other was a KV type. They extended 2.4 and 2.9 meters outward, respectively, and had a divergence angle of 70 degrees. The antennas were equipped with built-in springs that allowed them to open and move into position after the rocket separated.

In the back half of the satellite, there was a mechanism to detach from the rocket, which was used during orbit insertion.

History of Space Launches

In February 1955, the construction of the Baikonur test site in the Kazakhstan desert commenced, serving as the launch site for a groundbreaking mission. Following a series of tests, it became evident to the engineers that the R-7 rocket necessitated a reimagining of its head section, as it was unable to withstand the immense thermal loads. Additionally, efforts were made to reduce its weight as much as possible. By September 1957, an updated iteration of the R-7 was unveiled at the test site, boasting a weight reduction of 7 tons and featuring a dedicated compartment for a satellite in its head section.

The launch occurred at 22:28:34 Moscow time. After 4 minutes and 55 seconds, the rocket reached the necessary height and successfully entered the orbit. Just 20 seconds later, the satellite detached from the structure and began transmitting a simple signal: “Beep!”. This signal was received at the testing site for a duration of two minutes, until the spacecraft circled far away from Earth. Over a period of two weeks, the PS-1 transmitted various information through its transmitters before they eventually malfunctioned.

Fascinating fact: During the rocket launch, one of the engines experienced a delay in its fuel system and did not ignite immediately. It is estimated that if the engine had ignited just one second later, the P-7 would not have been able to achieve orbit.

The PS-1 spacecraft completed 1,440 orbits around the Earth during its 92-day mission. Over time, it experienced a gradual decrease in speed and altitude due to the effects of atmospheric friction. Eventually, it reached a point where it began to descend rapidly and ultimately burned up in the upper layers of the atmosphere.

Flight parameters

The flight characteristics of the PS-1 are as follows:

- Number of revolutions around the Earth – 1440;

- Apogee – 947 km;

- Perigee – 228 km;

- Duration of one full revolution – 96 min 12 sec;

- Orbital inclination – 65.1 deg;

- Radius of the PS-1 – 29 cm;

- Mass – 83.6 kg;

- Flight dates – from 04.10.1957 to 04.01.1958.

The primary goal of the satellite flight was to enhance the reputation of the USSR on a global scale. The successful launch of the first object into space created quite a sensation, especially when compared to the United States’ plans to send their own spacecraft. While the Americans were still publicly discussing their intentions, the Soviet Union took immediate action. This led to numerous articles in the press, with many adopting a “talk is cheap” perspective.

The satellite launch marked the beginning of human space exploration and initiated a fierce competition between the USA and the USSR. In response, the United States launched their own spacecraft, named “Explorer 1,” into orbit. This satellite entered orbit on February 1, 1958, but it wasn’t as captivating as the PS-1.

The satellite’s sounds

In order to ensure universal visibility of the satellite’s functioning, its creators programmed it to continuously transmit signals. This process was facilitated by an electromechanical relay, which emitted alternating signals at frequencies of 20 and 40 MHz, each lasting for 0.3-0.4 seconds. The intervals between these signals were consistent in duration.

The length of each signal directly correlated with the pressure and temperature measurements obtained from sensors within the satellite’s structure. By maintaining uniform transmission periods, the scientists were able to verify the proper operation of the PS-1 and the integrity of its internal environment. Throughout a span of two and a half weeks, the device emitted several million signals, each representing a simple “beep”.

The scientific findings from the initial launch of the man-made satellite

The PS-1 launch can be considered a resounding success, as the scientists were able to accomplish the objectives they had set. The flight yielded several noteworthy scientific findings, including:

- The acquisition of valuable flight test data from the first satellite.

- The opportunity to study the ionosphere, which reflects signals transmitted from the Earth’s surface.

- The satellite’s interaction with the atmosphere and its gradual decrease in velocity provided valuable insights into the density of the upper atmosphere.

- The gradual malfunctioning of PS-1 served as a valuable lesson and allowed for the development of subsequent vehicles that were more resilient to the harsh environment of space.

Scientists continuously monitored the position of the satellite and conducted various calculations while it was in orbit. Additionally, active information-gathering activities were carried out not only within the USSR but also internationally. For instance, researchers from the University of Sweden made significant progress in studying the ionosphere’s structure by observing the satellite’s behavior. The Soviet Union’s deliberate use of signal transmission on accessible frequencies enabled scientists from around the globe to collaborate on joint activities and experiments.

Response to the Satellite Launch

The satellite’s launch caused a tremendous stir worldwide. While most countries reacted positively, recognizing the potential it held, the United States had an exceptionally negative response. In the 1950s, the United States firmly believed that it was at the forefront of the space race, particularly after obtaining the advanced ballistic missile data from the Third Reich’s blueprints.

However, when the USSR successfully launched a satellite first, it came as a complete shock to the US, who had assumed they were the pioneers of space exploration. They were also confident that they would be the first to conquer it.

Did you know?: In the aftermath of the PS-1 launch, there was a Pentagon meeting where some American military officers proposed a unique idea – to launch tons of debris into space in order to block the Earth’s atmosphere and prevent further space exploration.

However, it is important to note that the Soviet Union’s early success in the space race served as a major catalyst for the United States. American designers and scientists were inspired to create a comprehensive space program that not only matched the Soviet Union’s achievements but eventually led to the historic moon landing. It is possible that if the United States had been the first to launch a satellite, their enthusiasm may have been dampened, and the iconic phrase “a small step for man and a giant leap for mankind” may never have been uttered.

The satellite launch received extensive coverage from the global press. Scientist Beniamino Segre publicly voiced his admiration for the groundbreaking achievement by the USSR, as he saw it as opening up new perspectives and opportunities. The New York Times noted that only a nation with advanced technology could embark on space exploration.

Designer Hermann Oberth, hailing from Germany, expressed his deep respect for Soviet scientists. According to him, only the brightest minds, undoubtedly present in the USSR, could successfully launch an object into orbit. Nobel Prize winner Joliot-Curie asserted that humanity was now free from the confines of Earth.

The world press continued to write about this event and celebrate the USSR’s accomplishment for a considerable period of time.

A fascinating video on the inaugural satellite

In the event that you come across any inaccuracies, kindly select the specific text segment and hit Ctrl+Enter.

Sputnik-1 – The initial man-made satellite to orbit the Earth was successfully launched by the USSR on October 4, 1957.

The satellite was officially known as PS-1 (Simplest Sputnik-1). It was launched from the 5th research range of the USSR Ministry of Defense, known as “Tyura-Tam” (later renamed Baikonur Cosmodrome), utilizing a Sputnik launch vehicle (R-7).

The launch date is widely recognized as the dawn of the space age for humanity, and in Russia, it is commemorated as a significant day for the Space Forces.

To mark this historic achievement, a 99-meter tall monument called “To the Conquerors of Space” was erected in Moscow on Prospekt Mira, near the VDNKh metro station. The monument portrays a rocket blasting off into the sky, leaving a trail of fire behind it.

On October 4, 2007, a commemorative statue was revealed in the city of Korolev to mark the 50th anniversary of the launch of PS-1, the first man-made satellite to orbit the Earth.

The development of this landmark achievement was led by S. P. Korolev, a pioneer of practical space travel, with contributions from renowned scientists such as M. V. Keldysh, M. K. Tikhonravov, N. S. Lidorenko, V. I. Lapko, and B. S. Chekunov, among others.

- Flight start – The flight began on October 4, 1957 at 19:28:34 GMT

- Flight end – The flight ended on January 4, 1958

- Vehicle weight – 83.6 kg;

- Maximum diameter – 0.58 m.

- Orbital inclination – 65.1°.

- Orbital period – 96.7 minutes.

- Perigee – 228 km.

- Apogee – 947 km.

- Number of orbits – 1440

Device

The device was composed of a pair of half-shells that were fastened together using 36 bolts and docking spars. A rubber gasket was used to ensure a tight seal between the two halves. The upper half-shell housed two antennas, each measuring 2.4 m and 2.9 m in length. Within the completely sealed enclosure, various components were installed, including an electrochemical power unit, a radio transmitter, a fan, a thermal relay, and the ducting for the thermal control system. Additionally, there was a switching device for the on-board electroautomatics, as well as temperature and pressure sensors, and an on-board cable network.

History of Space Launches

The launch of the very first satellite was preceded by extensive efforts from Soviet rocket designers led by Sergei Korolev.

1947-1957. A Decade of Advancements: From “Fau-2” to PS-1.

The story behind the First Sputnik is deeply intertwined with the development of rocket technology. Both the Soviet Union and the United States built upon the foundation laid by German scientists.

The V-2 rocket, which served as a blueprint for future advancements, incorporated the visionary ideas of exceptional individuals like Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, Herman Oberst, and Robert Goddard. This groundbreaking guided ballistic missile boasted the following key features:

- Maximum firing range: 270-300 km.

- Initial mass: up to 13,500 kg.

- Head mass: 1,075 kg.

- Fuel components: liquid oxygen and ethyl alcohol.

- Engine thrust at start: 27 tons.

An autonomous control system ensured a stable flight on the active section.

On May 13, 1946, Stalin signed a decree to establish rocket science and industry in the USSR. In August, S.P.Korolev was appointed as the chief designer for long-range ballistic missiles.

Little did we know at that time that, by working with Korolev, we would become part of the historic launch of the world’s first ISV into space, and soon after, witness the first manned mission.

In 1947, the Soviet Union began its work on rocket technology with the flight tests of Fau-2 rockets that had been assembled in Germany.

The R-1 rocket, an exact replica of the Fau-2, was successfully tested at the Kapustin Yar test site in 1948. This rocket was completely manufactured in the USSR. That same year, the government issued decrees for the development and testing of the R-2 rocket, which had a range of up to 600 km, as well as the design of a rocket with a range of up to 3,000 km and a head mass of 3 tons. In 1949, the R-1 rockets were utilized for a series of high-altitude launch experiments for space exploration. By 1950, the R-2 rockets were already undergoing testing and were officially adopted for service in 1951.

The development of the R-5 missile marked a significant departure from the Fau-2 technology, as it boasted a range of up to 1,200 kilometers. In 1953, these missiles underwent testing, which prompted further research into their potential as a means of delivering nuclear weapons. The missile underwent modifications to enhance its reliability, including the integration of atomic bomb automatics. Renamed the R-5M, this single-stage medium-range ballistic missile made history on February 2, 1956, when it became the world’s first missile capable of carrying nuclear warheads.

The Minister of Medium Machine Building, also known as Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers, Vyacheslav Aleksandrovich Malyshev made an unexpected visit to me. He strongly advised me to put aside any thoughts of the intercontinental missile being equipped with an atomic bomb. According to him, the designers of the hydrogen bomb have assured him that they can reduce its weight and make it only 3.5 tons for the rocket version. (source: “The First Space”, p. 15)

In January 1954, a chief designers’ meeting took place where they developed the fundamental principles for the rocket’s layout and ground launch equipment. They decided to deviate from the conventional launch table and instead use suspension on discarded trusses. This innovative approach helped to reduce the rocket’s mass by not burdening its lower part. Additionally, they made a significant change by replacing the gas-jet rudders, which had been traditionally used since the Fau-2 era, with twelve rudder engines. These engines were intended to serve as thrust engines for the second stage during the final stage of active flight.

On May 20, 1954, a government decree was issued regarding the advancement of a two-stage intercontinental missile known as the R-7. Shortly after, on May 27, Korolev submitted a report to the Minister of Defense Industry, D.F. Ustinov, regarding the development of an ISV (Intercontinental Ballistic Missile) and the potential for launching it using the future R-7 rocket. The basis for this report was a series of research conducted from 1950-1953 at NII-4 of the Ministry of Defense, led by M.K. Tikhonravov, titled “Studies on the Creation of an Artificial Earth Satellite.”

When we, as nuclear scientists, arrived at the scene, we were expecting something impressive. However, what we encountered was beyond our expectations, something on a whole new level. We were captivated by the immense technical culture that was visible even to the naked eye. The coordination and collaboration of hundreds of highly skilled individuals was remarkable, as they approached their work with a businesslike attitude, despite dealing with mind-boggling concepts.

– (comp. “The First Space”, p. 18)

On January 30, 1956, a government decree was signed to establish and launch an orbiting satellite in 1957-1958. This satellite, known as “Object D,” was designed to weigh between 1000-1400 kg and carry 200-300 kg of scientific equipment. The USSR Academy of Sciences was responsible for developing the necessary hardware, while the construction of the satellite was entrusted to OKB-1. The Ministry of Defense was in charge of launching the satellite. However, by the end of 1956, it became evident that building reliable satellite hardware within the given timeframe was not feasible.

On January 14, 1957, the USSR Council of Ministers gave its approval to the R-7 flight test program. Simultaneously, Korolev submitted a report to the Council of Ministers, stating that by April-June 1957, two satellite version rockets could be prepared and launched immediately after the initial successful launches of the intercontinental rocket. By February, while construction work at the test site was still ongoing, two missiles were already prepared for shipment. Recognizing the unrealistic timeline for the production of the orbital laboratory, Korolev presented an unexpected proposal to the government:

There are reports indicating that the United States plans to launch an ISR in 1958 in connection with the International Geophysical Year. We run the risk of losing our priority. Therefore, I suggest that instead of a complex laboratory, we put the simplest satellite, known as object “D,” into space.

The approval of this proposal took place on February 15.

Finally, on August 21, 1957, a successful launch took place when rocket No. 8L completed the entire active flight section and reached its target area – the test site in Kamchatka. Despite the fact that its head part was completely burned up upon entering the dense layers of the atmosphere, TASS reported on August 27 about the successful development of an intercontinental ballistic missile in the USSR. On September 7, the rocket had its second fully successful flight, but once again, the head part could not withstand the high temperatures. As a result, Korolev started making preparations for a space launch.

So, based on the results of flight tests for five missiles, it became evident that it had the capability to fly, but the head section required significant revision. According to the optimists’ estimates, this would take at least six months to complete. The destruction of the warheads cleared the path for the launch of the First Simple Satellite. (. )

S. P. Korolev received Khrushchev’s approval to utilize two rockets for the experimental launch of the most basic satellite.

The development of the most basic satellite commenced in November 1956, and by early September 1957, PS-1 had undergone final testing on a vibration test bench and in a thermal chamber. The satellite was designed as a highly simplistic vehicle equipped with two radio beacons for trajectory measurements. The transmitter range for the basic satellite was deliberately chosen so that it could be tracked by radio enthusiasts.

On September 22, the Tyura-Tam received the R-7 rocket #8K71PS (M1-PS Soyuz product). This particular rocket had undergone significant modifications to reduce its weight. The head section was replaced with a satellite transition, and the radio control system equipment and one of the telemetry systems were removed. Additionally, the engine shutdown automatics were simplified. As a result, the overall mass of the rocket was reduced by 7 tons.

By October 2, Korolev had signed an order for flight tests of the PS-1 and had sent a notification of readiness to Moscow. However, no responsive instructions were received, so Korolev took it upon himself to position the rocket with the satellite for launch.

At 22:28:34 Moscow time on October 4th (19:28:34 GMT), a successful launch took place. After 295 seconds, the PS-1 and the rocket’s 7.5 ton central unit were placed into an elliptical orbit with an altitude of 947 km at the highest point and 288 km at the lowest point. At 314.5 seconds after liftoff, the Sputnik separated and emitted its recognizable call sign, “Beep! Beep!” The Sputnik was visible for 2 minutes at the test site before disappearing over the horizon. The excitement was palpable as people at the cosmodrome rushed out into the street, shouting “Hurrah!” and embracing the designers and military personnel. Even on the first orbit, a TASS message proudly declared, “…Thanks to the tremendous efforts of research institutes and design bureaus, the world’s first artificial Earth satellite has been created…”

It was close, but the first achievement of space speed might not have happened.

However, the victors are not evaluated!

A remarkable feat was accomplished!

The satellite completed 1440 orbits around the Earth (approximately 60 million km) and flew for 92 days until January 4, 1958. Its radio transmitters remained operational for two weeks after launch.

The Importance of the Journey

– Ray Bradbury. "The initial glimmer of eternity…" (Space One anthology, 2007):

On that fateful evening when Sputnik initially streaked across the heavens, I lifted my gaze and contemplated the inevitable fate of the future. For within that minuscule luminosity, darting swiftly from one end of the celestial expanse to the other, lay the destiny of all humanity. It was clear to me that while the Russians exhibited unparalleled brilliance in their pursuits, we would soon follow suit and claim our rightful place among the stars. That celestial glow rendered mankind immortal, for our earthly abode could not serve as our sanctuary indefinitely; the specter of frigid or scorching demise loomed over it. Immortality was our predestined path, and the radiant gleam above me heralded its dawning.

I bestowed my blessings upon the Russians for their audacity and presciently anticipated the subsequent establishment of NASA by President Eisenhower in the wake of these momentous occurrences.

Scientific findings from the PS-1 mission

Despite lacking any scientific instruments, the PS-1 satellite yielded valuable scientific data through the analysis of its radio signals and optical observations of its orbit.

Following the satellite’s launch, a small team of scientists from the newly-established Kiruna Geophysical Observatory in Sweden (now known as the Swedish Space Physics Institute) [1] took notice of this event. Led by Bengt Hultqvist, they began measuring the ionosphere’s total electron composition using the Faraday effect. These measurements were subsequently continued in the subsequent satellite missions.

The Sternberg State Astronomical Institute of Moscow State University [2] assigned the task of optically observing ISVs to a team consisting of V. G. Kurt, P. V. Shcheglov, and V. F. Yesipov. These individuals developed a methodology for observing ISEs using optical instruments. F. Yesipov specifically developed a method for observing satellites with precise determination of their coordinates and time reference. To accomplish this, they adapted a NAFA aerial camera with a 10-cm lens and used a marine chronometer with electrical contacts to measure precise time intervals. After developing the film, they “georeferenced” the satellite tracks to star coordinates using a measuring microscope. They then manually determined six orbit parameters using mechanical calculating machines. The calculations took 30-60 minutes, whereas modern computers can complete such calculations in just 1-2 seconds. V. G. Kurt and P. V. Shcheglov made daily photographic observations of Sputnik-1’s orbit for two weeks in Tashkent at the Astronomical Observatory of the Academy of Sciences of Uzbekistan. The changes in the orbit provided a preliminary estimate of the atmospheric density at orbital altitudes, which surprised geophysicists due to its high value (around 10^8 atoms/cm^3). These measurements of high atmospheric density allowed for the development of a theory on satellite braking, with the foundations laid by M. L. Lidov [3].

Interactive Media

Fascinating Information

- The trajectory for inserting Sputnik-1 into orbit was initially calculated using electromechanical counting machines that resembled arithmometers. Only towards the final stages of the calculations was the BESM-1 computer utilized. (As mentioned in G.M.Grechko’s memoirs[4])