There are numerous intriguing theories surrounding the absence of a visible crater for the enigmatic Tunguska meteorite, which has puzzled scientists for over a hundred years. Let’s explore some of the most fascinating hypotheses.

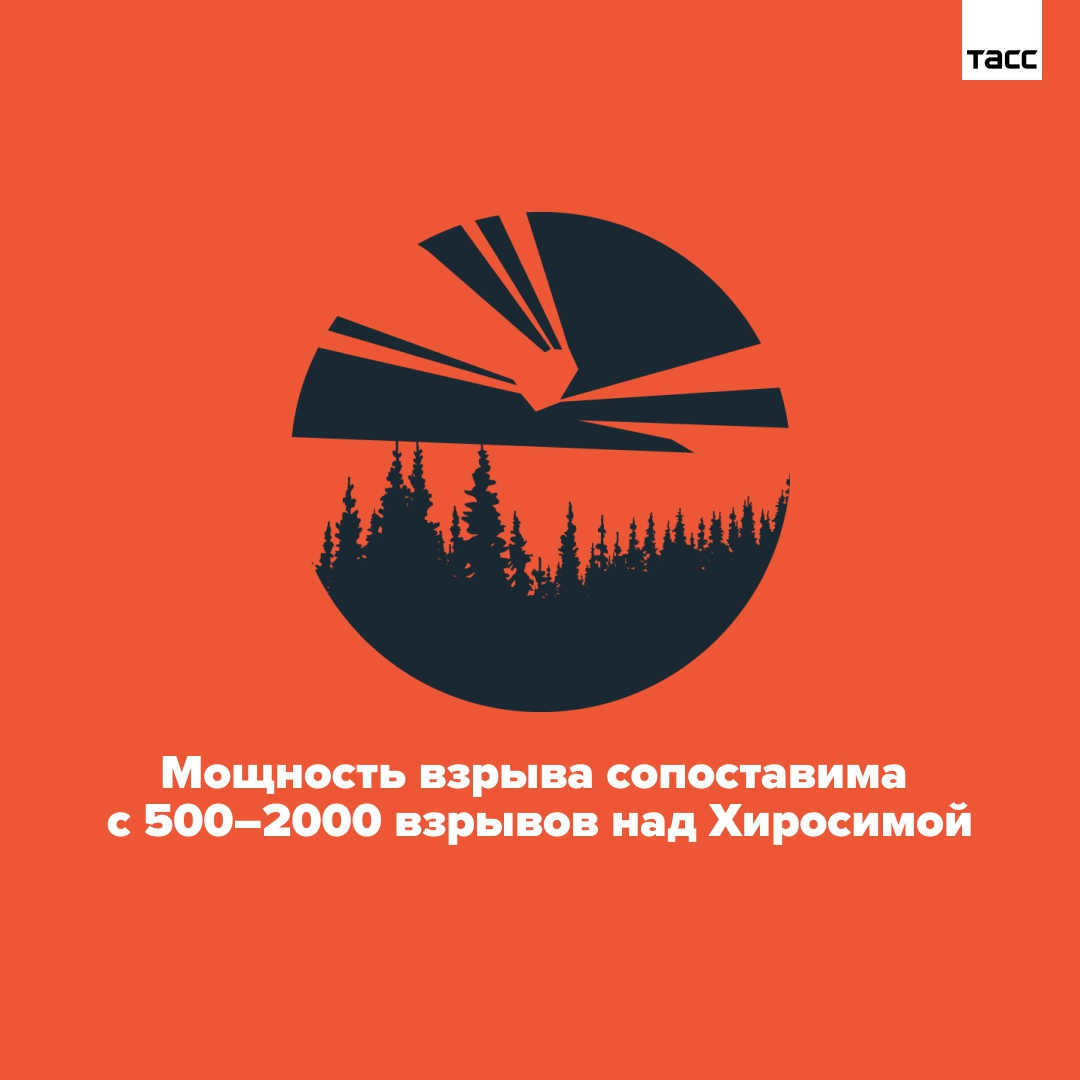

In the early hours of June 30, 1908, a tremendous crash resonated through Siberia as an unknown object made impact. The aftermath left 2150 square kilometers of forest devastated, equating to approximately 80 million trees reduced to charred fragments and debris. Witnesses recall a luminous sphere that caused windows to shatter and buildings to crumble. Researchers later classified the event as a meteor explosion, estimated to have a force of 30 megatons, occurring at an altitude of 10 to 15 kilometers.

Even though the crater itself has never been discovered, the search for fragments of meteoric ore continues to this day. And here are a few theories regarding the origin of the Tunguska meteorite and the evidence that supports them.

The Tunguska meteorite could possibly be the residue of a massive asteroid

An asteroid does not necessarily need to enter Earth’s atmosphere to cause the observed effect. It is plausible that a large object, primarily composed of iron, entering the Earth’s atmosphere at a shallow angle and then vanishing into space, could have created a similar destructive impact without leaving any discernible trace.

This is the current appearance of the Tunguska meteorite site, which still remains the subject of numerous hypotheses.

"The authors of this theory, including astronomer Daniil Khrennikov from the Siberian Federal University, have conducted a study on the passage of asteroids with diameters of 200, 100, and 50 meters through the Earth’s atmosphere. These asteroids were composed of three different materials – iron, stone, and water ice. The study focused on asteroids with a minimum trajectory height ranging from 10 to 15 kilometers. The results of the study have provided confirmation for our hypothesis, which offers an explanation for the Tunguska phenomenon – a longstanding mystery in the field of astronomy. According to our theory, the Tunguska incident was caused by the entry of an iron asteroid into the Earth’s atmosphere, followed by its return to a near-solar orbit."

The Hypothesis of the “Ice Body”

In the early theories surrounding the Tunguska meteorite, there was speculation that the object may have consisted of ice, similar to a comet. At first, this hypothesis seemed to provide a plausible explanation for various aspects of the event, such as the lack of fragments and the trace left behind, which could have been the result of the ice melting. However, Russian researchers in the 1970s were able to discredit this hypothesis quite easily. The intense heat generated by the object’s friction against the atmosphere would have caused the ice body to completely melt during its approach. Additionally, the increased pressure and air penetration would likely cause a stone meteor to break apart due to microcracks. Only iron meteors possess the stability to maintain their integrity.

Ultimately, it was discovered that the hypothesis suggesting the Tunguska meteorite was an icy body was incorrect. If it were a comet, it would have melted in the atmosphere.

That’s why scientists theorize that the most probable explanation for the Tunguska meteorite is a 100 to 200-meter-wide iron object that traveled 3,000 kilometers through the atmosphere. With these dimensions, it would have been moving at a speed of 7 m/s and flying at an altitude of 11 kilometers. This hypothesis accounts for several features of the Tunguska event. The absence of a crater can be attributed to the meteorite not actually making contact with the Earth’s surface. The lack of iron debris is also explained by the high velocity of the object, which would have caused it to heat up and lose material. The researchers suggest that any loss of mass could have been due to the sublimation of individual iron atoms, which would appear similar to common iron oxides and therefore indistinguishable from the surrounding soil.

Maybe this is the most incredible and beloved theory about the genesis of the Tunguska meteorite among Russian people. It was initially introduced in an edition of the “Around the World” magazine in 1946. However, the theory didn’t gain much traction, but it did serve as inspiration for numerous works of science fiction. Naturally, there was no enigmatic extraterrestrial vessel crashing into the planet and leaving behind such evidence. The notion of the Tunguska meteorite potentially being an alien spacecraft remains solely a hypothesis, which later became a popular theme in fiction.

The theory of antimatter explosion

Antimatter was once hailed as the ultimate solution for future energy needs due to its ability to release a tremendous amount of energy through annihilation. However, obtaining antimatter in significant quantities has proven to be an incredibly challenging task. As of now, antimatter remains one of the rarest and most expensive substances on Earth, with physicists unable to produce even a single gram.

The formation of the Tunguska meteorite crater is believed to have been caused by the celestial body’s passage through Earth’s atmosphere. Although the meteorite itself did not impact the ground, the resulting shockwave caused widespread destruction.

However, there was limited knowledge about the event in the previous century and in 1948. An article by Lincoln LaPaz was published in Popular Astronomy magazine, proposing the idea that the Tunguska anomaly might have been caused by an explosion of antimatter. The question then arises, where would this antimatter have originated from in the Siberian wilderness? One plausible explanation was that an antimatter comet collided with the Earth! This hypothesis regarding the Tunguska meteorite was presented in 1965, but it now seems absurd, as such a comet would have the capability to devastate half of the planet!

By the way, TechInsider now offers a new section called “Company Blogs”. If your organization wishes to share information about its activities, please get in touch with us.

The Tunguska event remains one of the greatest enigmas of the past century. Despite numerous accounts from witnesses and multiple expeditions, no fragments of the meteorite have ever been discovered. The prevailing theory in the scientific community is that the meteorite exploded in mid-air before reaching the Earth’s surface. However, scientists from Nizhny Novgorod have put forward the hypothesis that the meteorite did indeed make impact and have embarked on an expedition to search for the crater. Alexei Kiselev, a teacher at Mininsky University and participant of the expedition, shared the details of their findings with NN.RU.

History of the Tunguska meteorite

On the morning of June 30, 1908, a significant event occurred in central Siberia. The sky suddenly became illuminated by a massive fireball. Eyewitnesses described seeing a bluish-white object, although its visibility was hindered by the intense light.

The Krasnoyarets newspaper reported the terrifying scene: “On the island opposite the village, horses and cows began to scream and run frantically from one end to another. It felt as if the ground was about to split open and everything would be swallowed into the abyss.”

Shortly after, a powerful explosion occurred, followed by several more. The resulting shockwave caused trees to be knocked down over a two thousand kilometer area. In nearby settlements, windows rattled and objects fell from shelves. Evenks, whose camps were situated close to the forest, later recounted to researchers how the trees surrounding them caught fire and their reindeer scattered in fear after the intense thunderous sound.

Reactions to the event were diverse. The local population initially believed it was the Japanese (as the war with them had ended in 1905). The Evenks associated the celestial phenomenon with the descent of the deity Ogda, while science fiction writers speculated that the explosion was caused by the crash of a spaceship.

However, scientists at the time immediately hypothesized that a meteorite had passed over Siberia. The first scientific expedition was only able to be organized in 1921, when the Academy secured funding. This marked the beginning of a more extensive investigation into the Tunguska disaster.

Expeditions were launched in the area where it was believed the meteorite had fallen, but despite nearly a century of research, fragments of the celestial object have not been discovered.

Video: Alena Semakina, Anna Kurylyova, Vlad Cherkasov

What Nizhny Novgorod scientists aimed to discover

Alexei Kiselev developed an interest in the Tunguska catastrophe during his time in school. Over time, this fascination evolved into the study of meteorite craters. The scientist refers to himself as a pioneer in researching the meteoritic origins of Lake Svetloyar.

With the emergence of detailed photomaps of the Earth’s surface, such as Google Earth, Kiselev decided to observe the site where the Tunguska meteorite fell. This decision sparked further investigations. He took part in an international expedition in 2008, but it yielded no results. The next expedition had to be meticulously planned for several years.

– Our initial hypothesis was that the object did not explode in the air, but rather it descended and impacted the ground, creating a crater. It appears that we may have indeed discovered the meteorite crater from the Tunguska event, – the researcher stated.

This expedition was conducted during the summer and received support from Mininn University, where Alexey Kiselev is a professor. Andrei Antonov from the Institute of Applied Physics of the Russian Academy of Sciences also participated in the expedition. Additionally, Evgenia Moroz, an inspector from the Tunguska Nature Reserve, joined the team on-site. The three of them set out on their journey.

The location of the meteorite impact

Travelling over five thousand kilometers by plane from Moscow to the village of Vanavara in the Krasnoyarsk region, then approximately 70 kilometers along the rivers, and finally on foot. The journey was challenging, through forests and swampy terrain in persistent rain. It took the researchers several days to reach the spot where the crater could potentially be found.

– The cordons left the strongest impression on me. <. >After walking all day and passing through a cordon, it was such a relief and joy. Being able to melt a stove, warm up, sleep on a flat surface in a sleeping bag, and cook food on that stove without any smoke, soot, or other inconveniences,” recalls Alexey Kiselev.

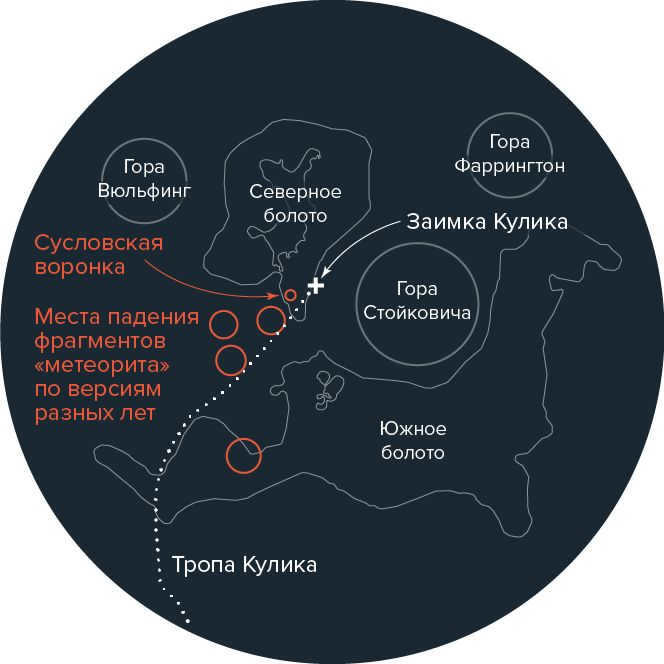

The objective of the expedition was to investigate the ring formation in the Southern Swamp, which, based on the scientist’s calculations, appeared to be a potential meteorite crater. This was supported by the forest debris map as well. Additionally, the surrounding swamp was described as “remarkably even and level,” which led Kiselev to believe it is relatively young.

The professor acknowledged that the epicenter, or designated target, is quite intricate. It is an ancient paleovolcano located in a mountainous region. He explained that the swamp has engulfed the crater, resulting in a flattened appearance.

– If this were occurring in the Nizhny Novgorod region, where there are sandy areas, we would immediately observe signs of an explosion. However, witnessing an explosion atop another explosion is rather perplexing,” the researcher remarked.

Scientists discovered an apparently typical marsh at the location, but its normality started to diminish upon closer inspection.

A century ago, a massive fireball descended and detonated in the Siberian wilderness. It can only be loosely referred to as a “meteorite” – none of the investigators have yet determined its true nature. TASS reporters have gathered all the theories regarding the incident in a dedicated project and have explained how to portray an event when no photographs exist.

The final concept of the project was formulated in the spring of 2018. Its objective is straightforward – to provide the user with comprehensive information regarding the Tunguska bolide, whether it is what we know or do not know about it.

Towards the end of 2017, when the decision to create a project commemorating the 110th anniversary of the Tunguska meteorite’s fall had just been made, I had initially planned to undertake the special project myself. I even managed to reach out to a potential expert and read one of his recommended books. However, in 2018, I assumed the role of the head of the TASS special projects group, leaving me with no time to delve into the subject matter. Consequently, I delegated the direct responsibilities of the project to my colleagues, Kristina Nedkova and Timur Fehretdinov.

Conducting a thorough fact-checking process for this unique project proved to be an insurmountable task: the entire history of the Tunguska phenomenon is shrouded in uncertainty, making it challenging to provide a comprehensive account.

In order to tackle this special project, we collaborated with the special projects group of the tass.ru website and the TASS Infographics Studio, while also enlisting the expertise of various specialists. As editors – myself, Timur, Sabina, and Alexander – we were responsible for sourcing these experts, asking them pertinent questions, establishing the project’s structure, crafting the written content, and ensuring factual accuracy. The Infographics Studio took charge of creating illustrations, designing the layout, finding visual solutions, and cultivating the overall ambiance of the material.

My intention was to encapsulate fifty percent of the narrative in “digital facts”, but unfortunately, there was a severe dearth of precise data available, leaving me with only general ranges. At a certain juncture, everything becomes a complete mess. The prospect of distorting the information is truly daunting, especially considering the absence of a reliable benchmark for comparison.

In this unique project, our aim was to capture the concept of time lost, showcasing how individuals postpone the investigation of significant incidents. While it is true that a century ago, the information landscape was not as extensive as it is today, and our knowledge about the Chelyabinsk meteorite surpasses that of the Tunguska event, it still leaves us astounded. It is difficult to fathom that in today’s modern world, someone would abandon the study of an explosion akin to Tunguska after just ten years due to reasons like “lack of time” or “skepticism about available information.”

From this objective, another, more transparent goal emerged – to reconstruct an occurrence that science has not yet thoroughly documented.

When it comes to ambiance, our inspiration was drawn from the iconic television show “Twin Peaks”. For a considerable period, the phrase “The Tunguska meteorite is not what it appears to be” served as the preliminary slogan for our project. The essence of this series aligns perfectly with our narrative about the eerie and mysterious Siberian wilderness, where even a colossal spacecraft can mysteriously vanish.

Transforming a static image into animated artwork

We had originally planned to release the content within a two-month timeframe, with the official release date set for June 30, 2018.

It took approximately two to three weeks just to create the specifications for the infographic and conduct thorough research. The expert provided us with books on the Tunguska event, which Christina, Sabina, Sabina, and I studied extensively, extracting important facts and figures. From the extensive 50-page document, we then attempted to distill the information that would best help us construct a coherent structure for the project.

Ultimately, we developed a relatively comprehensible model: the project’s narrative progressed from an emotional section featuring eyewitness accounts and a description of the explosion itself, to a more factual and hypothesis-driven presentation. It took an additional two weeks to finalize the text.

The completion of the illustrations was the final task on our list. Just a week before the project was set to be released, we made the decision to revamp a diagram depicting the aftermath of the meteorite impact. Originally, the diagram was intended to explain to readers the consequences of the explosion, but upon closer inspection, we realized that it was unclear and confusing. In order to rectify this, we reached out to Anton Mizinov, the art director at the Infographics Studio and a trained physicist. Within just five minutes, Anton was able to provide a clear outline of how the explosion affected the surrounding forest. This inspired us to create an animated explanation of the process.

During the initial phases, our intention was to create a soundtrack for the project “Tunguska Meteorite”, similar to what we did for “First Space”. I had started working on musical sketches and was enthusiastic about handling the sound design, including recording authentic forest sounds. However, as the team chose to lay out the project in Redimag instead of HTML, we had to abandon the idea of incorporating sound.

"No specific details will be provided"

There was minimal concrete information available regarding the incident: the exact time of the explosion, the extent of the affected area, and the number of trees that had fallen. The remainder of the details were based on eyewitness accounts and theoretical calculations, which varied from one another. The researchers investigating this phenomenon proposed numerous theories: some focused on the shape of the collapsed forest, while others relied on the testimony of eyewitnesses or seismograph data. We provided a brief overview of the main points of each theory, but many intriguing facts had to be simplified or omitted. If we were to include all the desired level of detail, it would have resulted in yet another scientific paper.

Nevertheless, each of the four specialists we collaborated with unanimously concurred on a certain aspect – the trajectory of the Tunguska “meteorite” endured for a duration ranging from five to fifteen minutes. I cannot fathom the emotions that those individuals must have felt as they beheld an unidentified fireball hurtling towards them for nearly a quarter of an hour. Personally, I would have promptly begun excavating a hole for myself right then and there.

It was my first experience creating 360° illustrations. When creating these illustrations, I carefully considered the different directions, the time of day, and the positioning of the sun in relation to the horizon during the meteorite’s fall. Throughout the process, I continuously reviewed the images in a player to ensure they looked good in 360° and to quickly identify any flaws.

Aside from the challenges of dealing with distortions in the panoramic view, finding suitable references proved to be quite difficult. There were very few photographs available from the Tunguska Nature Reserve, satellite maps were of low resolution, and historical photos of the forest devastation were also of terrible quality. As a result, I had to meticulously piece together a believable landscape.

Our Digital Marketing team also considers this product a success. After being released for a month, the project has accumulated 200,000 views. Despite its lengthy nature, being a traditional “sheet”, over fifty percent of users have read it halfway through, and twenty-five percent have reached the final section titled “The project was completed”. This is a remarkable achievement.

Tips from the authors

Simplicity is key. When starting to work on a topic, it’s natural to want to include everything you know about it. However, this can lead to information overload. Take a step back and filter the information, keeping only what truly impresses and engages the audience.

Learn from the past. Before diving into your chosen topic, research what has already been done. There are often areas where multimedia projects have already pushed the boundaries.

If there is already material available on a specific topic but it doesn’t address an important problem, repackage the existing data and approach it from a different angle. For example, this is exactly what we did with our project “When Napoleon Came” about the 1812 Patriotic War.

It was on June 30, 1908 when an enigmatic entity, later identified as the Tunguska meteorite, detonated and plummeted through the Earth’s atmosphere.

Location of Impact

The region between the Lena and Podkamennaya Tunguska rivers in Eastern Siberia has forever been marked as the spot where the Tunguska meteorite descended from the sky, blazing like the sun and traversing several hundred kilometers before it landed, leaving behind a trail of fire.

Photo: the alleged location of the Tunguska meteorite impact

Explosions were heard for nearly a thousand kilometers in all directions. The extraterrestrial object’s journey ended with a massive explosion above the uninhabited taiga at an elevation of approximately 5 – 10 kilometers, followed by a continuous collapse of the forest in the Kimchu and Khushmo interfluve – tributaries of the Podkamennaya Tunguska River, 65 kilometers away from the village of Vanavara (Evenkia). The residents of Vanavara and the few nomadic Evenks who were in the taiga at the time became firsthand witnesses to the cosmic disaster. The location of the Tunguska meteorite impact can be viewed on Google maps.

Weight

Scientists have estimated the weight of the space alien based on the scattering of particles, their concentration, and the estimated power of the explosion. In initial approximations, it has been determined that the Tunguska meteorite weighed approximately 5 million tons.

Expeditions

When it comes to observed phenomena, it is hard to find a more grandiose and mysterious event than the Tunguska meteorite. The first investigations into this phenomenon began in the 1920s. Four expeditions, led by mineralogist Leonid Kulik and organized by the USSR Academy of Sciences, were sent to the site of the object’s fall. However, even after 100 years, the mystery surrounding the Tunguska event remains unresolved.

Image: Portion of the Tunguska meteorite

In 2006, Yuri Lavbin, the president of the “Tunguska Space Phenomenon” fund, reported a significant finding near the Podkamennaya Tunguska River. It was discovered by researchers from Krasnoyarsk, at the exact location where the Tunguska meteorite had impacted. The researchers stumbled upon quartz cobbles that bore enigmatic writings.

As per the researchers, the peculiar symbols were applied to the surface of quartz in an artificial manner, presumably through the impact of plasma. Analyses of quartz cobbles, which were examined in Krasnoyarsk and Moscow, revealed that quartz contains impurities of cosmic substances that cannot be obtained on Earth. The studies validated that the cobbles are man-made objects: many of them are fused layers of plates, each adorned with symbols from an unfamiliar alphabet. According to Lovebin’s theory, the quartz cobbles are fragments of an information repository dispatched to our planet by an extraterrestrial civilization and detonated due to an unsuccessful landing.

There have been over a hundred various theories regarding the events that took place in the Tunguska taiga: from the ignition of marsh gas to the collision of an extraterrestrial spacecraft. It has also been proposed that a meteorite composed of iron or rock with nickel-iron inclusions; a frozen comet core; an unidentified flying object, possibly a spaceship; a massive ball of lightning; a meteorite from Mars, challenging to differentiate from earthly rocks, may have descended to Earth. American physicists Albert Jackson and Michael Rian put forth the idea that the Earth had encountered a black hole; some scientists suggested it was an extraordinary laser beam or a fragment of plasma that had detached from the Sun; French astronomer and expert on optical anomalies Felix de Roy proposed that on June 30th, the Earth likely collided with a cloud of cosmic dust.

A frozen comet

The most recent theory is the ice comet hypothesis, proposed by physicist Gennady Bybin, who has been studying the Tunguska anomaly for over 30 years. Bybin suggests that the enigmatic object was not a rocky meteorite, but rather a comet made of ice. This conclusion is based on the diaries of Leonid Kulik, the first researcher to investigate the site of the supposed meteorite impact. Kulik discovered a substance resembling ice covered in peat at the site, but he did not give it much significance as he was searching for something else entirely. However, Bybin argues that this compressed ice containing combustible gases, which was found 20 years after the explosion, is not evidence of permafrost as previously believed, but rather proof that the theory of an icy comet is correct. According to Bybin, the comet, shattered upon impact with our planet, turned Earth into a scorching hot frying pan, causing the ice to melt and explode. Bybin hopes that his hypothesis will be recognized as the only true and final explanation.

However, the prevailing belief among scientists is that the event was caused by a meteorite, specifically one that exploded in the Earth’s atmosphere. The search for evidence of this meteorite began in 1927, when the first scientific expeditions led by Leonid Kulik were launched in the area of the explosion. Surprisingly, no typical meteor crater was found at the impact site. Instead, the expeditions discovered that the surrounding forest had been flattened in a fan-like pattern, with the center of the blast leaving trees standing but stripped of their branches.

Following expeditions observed that the fallen forest area possesses a distinct butterfly pattern, oriented from the east-southeast to the west-northwest. The overall extent of the fallen forest encompasses approximately 2200 square kilometers. By simulating the shape of this region and conducting computer calculations considering all the factors of the impact, it has been determined that the explosion occurred not upon contact with the Earth’s surface, but rather in the atmosphere at an elevation of 5 – 10 kilometers.

Tesla Motors

“During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, there arose the theory linking Nikola Tesla to the Tunguska meteorite. According to this theory, on the day of the Tunguska event (June 30, 1908), Tesla conducted an experiment involving the transmission of energy through the air. Several months prior to the explosion, Tesla had claimed that he could illuminate the path for Robert Peary’s expedition to the North Pole. Furthermore, there are surviving journal entries in the U.S. Library of Congress in which Tesla requested maps of the least populated regions of Siberia. His experiments on the creation of standing waves, which supposedly involved a powerful electric impulse concentrated thousands of kilometers away in the Indian Ocean, align well with this hypothesis. If Tesla was able to enhance the impulse with the energy of the hypothetical “ether” (a medium believed in the past to be responsible for electromagnetic interactions) and utilize resonance to manipulate the wave, then, according to legend, there would be a release of power comparable to a nuclear explosion.”

Different theories

Various theories have been proposed to explain the Tunguska phenomenon. A well-known science fiction writer, Alexander Kazantsev, suggested that the event was caused by a spaceship from Mars. Another literary duo, Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, humorously proposed the idea of “contramoths” in their book “Monday Begins on Saturday.” According to this theory, the events of 1908 were not the result of a spaceship’s arrival on Earth, but rather the reversal of time caused by its departure.

However, these are merely conjectures, and the enigma of the Tunguska meteorite continues to elude us.