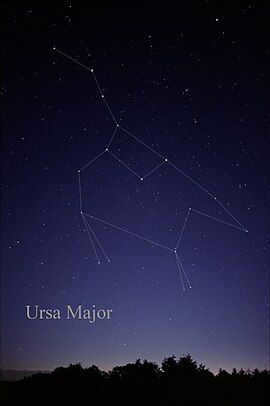

The Big Bear constellation, also known as Ursa Major, consists of seven magnificent stars that can be easily located in the night sky. These stars, which are of second magnitude, form the shape of a dipper, with the smallest star located in the upper left corner. In addition to these seven stars, there are 125 more stars in the constellation that shine brighter than the 6th magnitude.

Dimensions of the Big Dipper constellation

The Big Dipper constellation covers an area of 1,280 square degrees in the night sky, making it one of the largest constellations. Its size extends far beyond the boundaries of the familiar “bucket and handle” shape. Scientific measurements have revealed interesting facts about the stars within the “bucket”. For instance, these stars are located at varying distances from Earth. The closest star, Aliot, is approximately 50 light years away, while the most distant star, Benetnash, is about four times farther. Additionally, near the star Mizar (which translates to “horse” in Arabic), there is an almost invisible star called Alcor (also known as the “rider”) with a fifth magnitude.

The Significance of the Big Dipper in Astronomy

The Big Dipper serves as an excellent starting point and reference for amateur astronomers who are just starting out:

- By using this constellation as a guide, beginners can easily locate and identify numerous other constellations.

- It provides a clear demonstration of the apparent daily movement of the celestial sphere and the changing view of the night sky throughout the year.

- By memorizing the angular distances between the stars in the “bucket” of the Big Dipper, approximate angular measurements can be made.

- Astronomy enthusiasts with a modest telescope can observe double and variable stars within the Big Dipper that are not visible to the naked eye. They can even distinguish certain galaxies, such as the famous “exploding galaxy” M82.

Myths and Legends Surrounding the Big Dipper Constellation

The constellation “dipper” has been familiar to humans since ancient times. According to ancient Greek mythology, the constellation Big Dipper represents the nymph Callisto, who was a companion of Artemis and Zeus’ beloved. However, Callisto incurred the wrath of Artemis when she violated the rules of the goddess’ companions. In response, Artemis transformed Callisto into a bear and released dogs to hunt her down. To protect his beloved, Zeus had no choice but to raise Callisto to the sky, where she became the constellation Big Dipper.

Nevertheless, this occurrence is rather obscure: it is plausible that Zeus, in order to conceal his own infidelity from his jealous wife Hera, transformed Callisto into a bear, while Artemis arranged a hunt for her, either by accident or as a way of teaching the cunning and vengeful Hera a lesson. Alternatively, it is possible that Hera herself, out of a desire for revenge, transformed Callisto into a constellation, and the hunt for her was mistakenly organized by Callisto’s son Arcades. Alongside this narrative, there is also mention of an unidentified companion of Callisto, who was simultaneously transformed into the Little Dipper.

According to Philemon, there is another legend about the young Zeus. It claims that when his father Kronus tried to find and devour him, Zeus had to transform himself into a serpent and his caretakers into bears. This story explains the origins of the Big and Little Dippers, as well as the Serpent constellation. It is important to note that the Serpent constellation is likely the Dragon, and all three constellations are situated close together. Nevertheless, this myth is most likely a mere work of poetic imagination.

The Big Dipper on the Map of Constellations

During the daytime, the Big Dipper can be observed. You can effortlessly accomplish this by locating it on any of the interactive constellation maps. Furthermore, on these maps, you can discover numerous other prominent and minor constellations and examine them in detail. The power to explore is within your grasp!

Polaris, the brightest and closest pulsating variable star of the Cepheus delta type with a period of 3.97 days, stands out for its unique characteristics. Unlike other Cepheids, Polaris experiences a gradual fading of its pulsations over the course of several decades. In 1900, the star’s brightness change was recorded at 8%, which decreased to about 2% in 2005. Interestingly, Polaris has also exhibited a 15% increase in average brightness during this period.

What makes Polaris even more fascinating is the fact that it is actually a triple star system. At the core of this system lies the supergiant star, Polar A (α UMi A), which shines 2000 times brighter than our Sun and boasts a mass 6.4-6.7 times greater. With a radius of 47-50 solar radii and an age ranging from 55-65 million years, Polar A truly dominates the system.

Located at a considerable distance from Polar A (2400 a.e.), we find Polar B (α UMi B), a star with a mass of 1.39 solar masses. Due to its relative proximity, Polar B can be easily observed through telescopes even from the surface of the Earth.

In 1929, a study of Polaris’ spectrum discovered that it is a close binary star, a prediction made by earlier observations in 1924 by J. H. Moore and E. A. Kholodovsky. The companion star, known as Polaris A, is located at a distance of 18.5 astronomical units from Polaris. Polaris P (also known as α UMi P or α UMi a, or α UMi Ab) has a mass of 1.26 solar masses and is in such close proximity to the supergiant that it could only be captured by the Hubble telescope, and even then, only after the equipment was adjusted. The estimated orbital period of Polaris P around α UMi A is approximately 30 years.

Polar B orbits the α UMi A/P binary system over a period of approximately 100,000 years. Additionally, there are two other distant components, designated as α UMi C and α UMi D, but these stars are much older and are not physically connected to Polaris.

There is a possibility that Polaris and the stars around it are the remaining parts of a dispersed and impoverished cluster. Based on the data from Hipparcos and 2MASS, the radial velocities of the closest stars to Polaris are almost the same, and their average distance from Earth is about 100 parsecs. An analysis of the “color – stellar magnitude” diagram for the cluster suggests that its members, including Polaris, have an approximate age of 80 million years.

In 1990, the European space telescope Hipparcos determined that Polaris is located approximately 434 light-years away. Subsequent estimates in 2006 (Turner) and 2008 (Usenko, Klochkova) suggested distances of 330 and 359 light-years, respectively. However, a high-resolution measurement conducted in 2012 by a team of astronomers led by David Turner of Canada’s St. Mary’s University, using data from Russia’s six-meter BTA telescope, provided a more precise estimate of 99 parsecs (equivalent to 323 light-years). The most recent estimate, obtained in 2018 through data collected by the Gaia space telescope, indicates that Polaris is situated at a distance of approximately 447 ± 1.6 light-years.

The distance to Polaris, being a type cepheid, plays a crucial role in estimating distances to other galaxies. By refining this distance, scientists can improve the overall accuracy of the distance scale and also gain insights into the mass of dark matter.

A heartwarming tale of light and darkness

Dreamcatcher – Celestial

The sky is a reflection of the soul, a representation of its existence. The sun in the sky represents the center of the spiritual life, the mind. Balloons floating in the gray sky indicate a temporary collapse of all hopes. The daylight sky always symbolizes events in the soul’s life that can be clearly understood. Seeing a clear sky or light clouds without the sun signifies calm moments and inner focus, which can be used for spiritual growth. Beautiful clouds in the sky, with their slow movement and changing shapes, represent the harmonious life of the soul. Seeing a single bright cloud in the sky is a sign of something positive. And when it’s above your head, it signifies honor. Clouds moving rapidly across the sky symbolize interference from the outside world in your spiritual journey, unpleasant and sudden changes in mood, worldly troubles, and worries. Feathery clouds represent hidden sorrows that uplift. Clouds approaching on the horizon indicate fears and anxieties. A gloomy sky covered in clouds is a call for patience and temporary difficulties. Thunderstorms and storms high in the sky represent unnatural conditions in the soul’s life. A red sky signifies quarrels and disagreements, while a yellow or greenish sky indicates anger and envy. Ascending into the sky signifies a life of constant labor. Being in the clouds represents receiving news or attaining a new position. The night sky symbolizes phenomena in the soul’s life that lie beyond conscious awareness, a mystery to the waking self. A gloomy night sky without stars suggests a time of testing, where one must rely solely on the “higher world,” an unfavorable period for tranquil spiritual work. A sky filled with stars represents the fulfillment of secret desires, joy, and a sign that the soul is in the hands of the higher self. Brightly burning stars signify a happy future, while a clouded sky with a light haze suggests hidden sadness. Seeing a bright milky way represents hopes that are beyond the strength of the soul and help from above, highlighting the inseparable connection between outer life and the realm beyond.

Exploring the World Around Us

Marveling at the Springtime Starry Sky

- Which constellations were visible in the winter sky?

- How did we locate Polaris, and what makes it fascinating?

- Where was the Big Dipper situated in the winter sky?

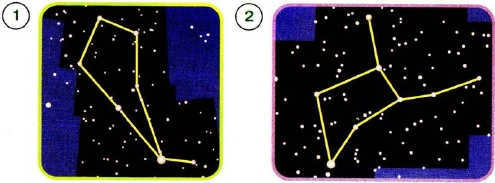

As spring arrives, we once again have the opportunity to observe the Big Dipper constellation in the starry sky. It is evident that its dipper has rotated and now appears differently compared to the autumn or winter. Let’s try to locate Polaris. It remains in the same position, while the other stars of the Little Dipper have shifted.

Let’s continue following the path we previously took to locate Polaris. This route will guide us towards a constellation known as Cassiopeia. It derives its name from a queen featured in the ancient Greek myths. The primary stars of the Cassiopeia constellation form a remarkable shape resembling the letter “M” elongated by its “legs”. During the spring season, this letter appears upside down. Imagine it positioned on its “legs”. This is how it will appear in the fall.

The Cassiopeia constellation, along with the Big Dipper and Little Dipper, can be observed in the sky year-round.

- Observe the illustration. Contrast the positioning of the Great Bear with what we observed during the autumn and winter seasons. In what way has the positioning of the Little Bear altered in comparison to the winter?

- Utilize the illustration to demonstrate how the constellation of the Big Dipper aids in locating the constellation Cassiopeia in the celestial sphere. Pair the diagram of the constellation Cassiopeia with an ancient illustration.

The lion, known as the king of beasts, holds a prominent position in the vast expanse of the starry sky.

Now let’s turn our attention to the opposite side of the sky, where the arrangement of stars has undergone a transformation since winter. New constellations have emerged, with one of the most captivating being Leo. Its primary stars come together to form a figure resembling a regal lion reclining in all its glory.

At the forefront of this constellation lies its brightest star, named Regulus, which aptly translates to “king.”

Take a look at the diagram provided. Notice the presence of several stars that are aligned in a graceful curve, resembling a sickle. These stars serve as easy markers for locating the constellation Leo. They represent the lion’s head, neck, and chest, all part of the mythical lion depicted in ancient drawings.

Why don’t we explore the guidebook that defines the constellation of Ursa Major?

- What is the reason for the stationary position of Polaris during different times of the year, while the Big Dipper, Little Dipper, and Cassiopeia constellations revolve around it (11)?

- Which familiar constellations can be observed in the sky during spring?

- How can one locate and identify the Cassiopeia constellation in the night sky? What makes it intriguing?

- What is the significance behind one of the constellations being named after the king of beasts?

During the spring season, the night sky offers a view of the well-known Big Dipper and Little Dipper constellations. Adjacent to them is the Cassiopeia constellation, while the opposite part of the sky features the Leo constellation.

Description

Rephrase the text, making it unique, using the English language while preserving the HTML markup.

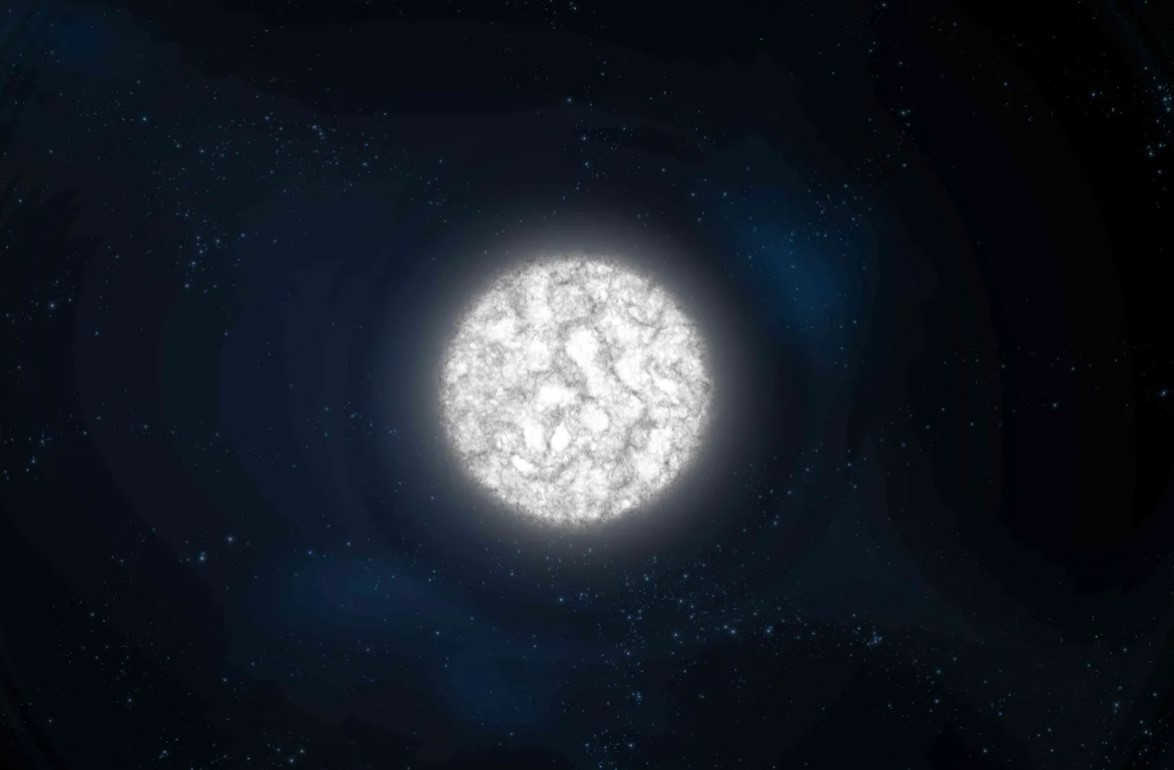

The photograph captures the nebula surrounding Polaris, taken with a long exposure.

Physically, Polaris is quite typical for a supergiant star. When observed through a small telescope or even binoculars, the star appears yellowish in color, which may come as a surprise to those accustomed to perceiving it as white. Its surface temperature is only slightly hotter than that of our Sun, hovering around 6000 K. However, the similarities end there.

Like many other stars visible to the naked eye, Polaris outshines the Sun when viewed from the same distance. Spectral analysis has revealed that it belongs to the supergiant classification. With a diameter 23 times larger than that of our Sun and a luminosity 2500 times greater, Polaris even surpasses Sirius in terms of sheer magnitude.

The primary celestial bodies in the constellation of Ursa Minor

Thoroughly explore the luminous celestial bodies within the Ursa Minor constellation, located in the northern hemisphere, through comprehensive descriptions, photographs, and characterizations.

Polaris (also known as Alpha Ursae Minoris) is a multiple star system (classified as F7:Ib-II) with an apparent magnitude of 1.985 and a distance of 434 light-years. It has been the nearest prominent star to the north celestial pole since the Middle Ages and remains the brightest star within the Ursa Minor constellation.

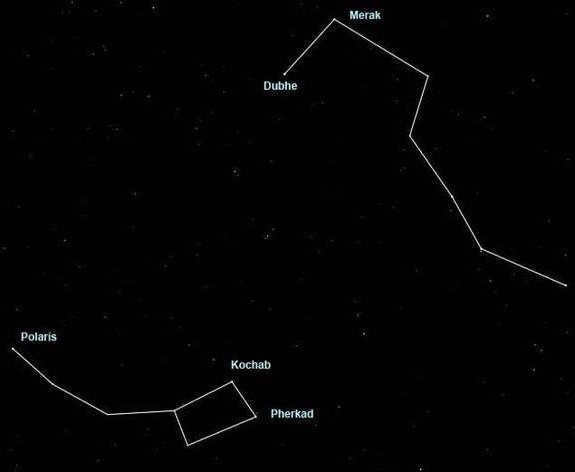

To locate Polaris, follow the stars Dubhe and Merak, the two brightest stars at the end of the Big Dipper asterism.

Polaris is comprised of the prominent star A, along with two smaller companion stars, B and Ab, and two more distant stars, C and D.

The most luminous celestial body in Cepheus is a massive giant (II) or supergiant (Ib) with a spectral classification of F8. It possesses a staggering mass that is six times greater than that of our sun. In the year 1780, the renowned astronomer William Herschel made the groundbreaking discovery that B is a main-sequence star of the spectral class F3, while Ab is a diminutive dwarf star that resides in a remarkably close orbit.

Polaris, also known as the North Star, is a variable star that belongs to the constellation of Cepheus. Its variability was first established by the Danish astronomer Einar Hertzsprung in 1911. During the time of Ptolemy’s observations, Polaris exhibited a magnitude of the third degree, but today it shines with a magnitude of the second degree. Due to its extraordinary brightness and its close proximity to the celestial pole, Polaris serves as an indispensable tool for astronomers engaged in celestial navigation.

The constellation Ursa Major is home to two famous asterisms: the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper.

Beta Ursae Minoris, also known as Kochab, is a colossal giant star of spectral class K4 III. Boasting a visual magnitude of 2.08, it is the most radiant star within the bowl of the Little Dipper. Situated at a distance of 130.9 light-years from Earth, it serves as a prominent companion to Polaris. Beta Ursae Minoris, along with its neighbor Gamma Ursae Minoris, is often referred to as the Guardians of the Pole due to their apparent orbital motion around Polaris.

From 1500 BC to 500 AD, they were a pair of twin stars that held the title of being the brightest stars closest to the north celestial pole. Kohab, which is 130 times more luminous than the Sun and 2.2 times more massive, is one of these stars.

Their traditional name, Kohab, is derived from the Arabic word “al-kawkab,” which means “star.” It is actually an abbreviation of “al-kawkab al-šamāliyy,” meaning “the northern star.”

Ferkad, also known as Gamma of the Little Bear, is a type A star with an apparent magnitude of 3.05. It is located 487 light-years away and falls under the A3 lab classification. This star has a rotational velocity of 180 km/s and is 15 times larger than our Sun in terms of radius. Additionally, it shines 1,100 times brighter than the Sun.

Ferkad is an interesting star because it possesses a gas disk at its equator, which causes fluctuations in its stellar magnitude.

The name Ferkad comes from the Arabic word for “calf.”

Yildun, also known as Little Bear Delta, is a white dwarf star that belongs to the main sequence and has a visual magnitude of 4.35. It is located at a distance of 183 light-years. The name Yildun translates to “star” in Turkish.

Zeta, a star in the Little Dipper constellation, is a main sequence dwarf star (A3Vn) with a visual magnitude of 4.32. It is located approximately 380 light-years away. Zeta is on the verge of becoming a giant star, with a mass 3.4 times that of the Sun and brightness 200 times greater. Its surface temperature is 8700 K. Zeta is also classified as a suspected Delta Shield variable.

The name aḫfa al-farqadayn, derived from Arabic, means “leading two calves.”

This particular Little Bear is a yellow-white main sequence dwarf star (F5 V) with a visual magnitude of 4.95. It is located at a distance of 97.3 light-years and can be easily observed without the use of technology.

The Arabic translation for its name is “brighter than two calves.”

Epsilon of the Little Bear is a triple star system located 347 light-years away. Epsilon A is a yellow giant of the G-type (a double star with an eclipsing spectroscopic nature), and B is a star of magnitude 11, located at a distance of 77 angular seconds.

Epsilon A is also classified as an RS Hound Dog variable. The brightness of this binary system fluctuates as one object periodically eclipses the other. The total brightness ranges from 4.19 to 4.23 with a period of 39.48 days.

Meteor showers from the Little Dipper

The Little Dipper is the source of the final meteor shower of the year, known as a “starburst”, which is not well-studied. The radiant of this meteor shower is located near the Little Dipper constellation, and it occurs between December 17 and 25, but its activity is highly unpredictable. Typically, during the most active days, observers may see between 10 to 20 meteors per hour, which may not be particularly exciting for the average stargazer. However, there are occasional bursts of activity when the number of meteors exceeds one hundred. These particularly active years for the meteor shower were 1988, 1994, 2000, 2006, and especially 1945 and 1986. This meteor stream is the northernmost of its kind and is believed to originate from the short-period comet Tuttle.

Aside from the primary celestial bodies in the Little Dipper, there is also a noteworthy collection of galaxies within it. One such galaxy, the aforementioned Dwarf, functions as a companion to the Milky Way and was first discovered back in 1954. This galaxy is quite ancient, estimated to be at least ten billion years old. Due to its diminutive size, it is difficult to determine whether it contains any gas, dust, or ongoing star formation processes. Additionally, it is sometimes referred to as Polarissima due to its proximity to the Earth’s rotational axis.

Furthermore, the Little Dipper constellation is home to the galaxies NGC 6217 and NGC 5832. All of these cosmic entities are relatively minuscule in terms of scale, making it necessary to employ high-quality optical equipment in order to observe them.

The Big Dipper’s Role in Locating Polaris

What is the primary purpose of the Big Dipper? It serves as a guide to Polaris.

Let’s locate Polaris using this constellation of seven stars. We can connect the two outer stars in the bucket (Merak and Dubhe) with an imaginary line. Then, we extend the line from Merak to Dubhe, increasing the distance by 5 times. Polaris is practically at the end of this line.

While the position of the Big Dipper changes throughout the seasons, Polaris remains in the same location. The method of finding Polaris using the outer stars of the Big Dipper is applicable all year round. Figure:

Stellarium

Contrary to popular belief, Polaris is not very bright. Its brightness is approximately equal to the stars in the Big Dipper.

The two outermost stars of the Big Dipper, Dubhe and Merak, always point towards Polaris no matter where the dipper is in the sky. Illustration:

G. Rey. Stars

3 How to locate the Little Dipper – an additional guidepost

If you have located Polaris but can’t find the Little Dipper, the large stars on the front edge of the dipper’s bowl – Kochab and Pherkad – can assist you.

- Turn your attention to the left side of Polaris and observe a light-colored circle within an orange halo – this is Kochab, and above it, creating the upper corner of the bowl – Pherkad. These stars revolve around Polaris and are known as the Guardians of the Pole.

- Take a closer look, and you will notice two additional stars forming the inner corners of the bowl. Connect them with lines, and you have a dipper without a handle.

- Search for two faintly shining star dots between the cup and the North Star. Join the remaining spaces with straight lines and a tiny ladle with a handle pointing in the opposite direction from the handle of the Big Dipper appears.

- Although the Little Dipper can be spotted at any time, it is most clearly visible in the winter sky before dawn or during the initial hour of sunset in spring.

If you have some free time, consider immersing yourself in nature as a way to unwind from the busy city life. It’s an opportunity to marvel at the beautiful constellation of stars in the night sky and contemplate the existence of distant and unknown worlds that remain beyond our reach.

About this article

Contributor(s):

WikiHow Staff Editor

This article has been meticulously crafted and reviewed by our experienced team of editors and researchers to ensure its accuracy and completeness. At wikiHow, we have a strict quality control process in place to uphold our high standards. This article has been viewed 7192 times.

Categories: Favorite Article Learning Hiking

English: Find the North Star

Français: trouver l’étoile Polaire

Deutsch: Den Polarstern finden

Português: Encontrar a Estrela do Norte

Italian: Finding the North Star

Spanish: Identifying the North Star

Indonesian: Finding the North Star

Dutch: Discovering the North Star

The enigmas of Ursa Major: various perspectives

Ancient Egypt’s “Bull’s Thigh”

The ancient Egyptians were pioneers in the field of astronomy, with some of their circular stone “observatories” dating back to the fifth millennium B.C. They established the basis for the constellation system, which was later adopted by medieval people, the Greeks, the Arabs, and modern science. During that distant era, the North Star was not Polaris, but Alpha of the Dragon (Tuban), due to the Earth’s axis precession. The Egyptians regarded this region, along with the nearby stars, as the “fixed sky,” believed to be the abode of the gods. Instead of the Big Dipper, the priests could see Seth’s leg, the god of war and death, who transformed into a bull and fatally struck Osiris with his hoof. In retaliation for his father’s murder, Horus, with a falcon head, severed Seth’s limb.

The astronomers from ancient China had a unique way of dividing the sky into 28 vertical sectors known as “houses.” These houses represent the path that the Moon takes during its monthly journey. This concept is similar to how the Sun moves through the signs of the Zodiac in Western astrology, which was originally borrowed from the Egyptians and divided into 12 sectors.

In the center of the sky, the Chinese astronomers had Polaris, also known as the North Star. This star held a significant position, similar to how the emperor resides in the capital of the state. Additionally, there were seven bright stars from the Big Dipper located near Polaris within the Purple Enclosure. The Purple Enclosure is one of the three Enclosures that surround the palace of the “royal” star.

These stars can be described as the Northern Bucket and their orientation corresponds to the seasons. They can also be seen as part of the carriage of the Heavenly Emperor Shandi.

India’s Seven Wise Men

Ancient India’s understanding of astronomy did not achieve the same level of brilliance as its mathematics. The concepts and ideas in this field were heavily influenced by both Greece and China. For instance, the 27-28 “stands” (known as nakshatras) that the Moon passes through in approximately a month bear a strong resemblance to the Chinese lunar “houses”. Additionally, Hindus placed great significance on Polaris, which the Vedas experts believed to be the dwelling place of Vishnu himself. The cluster of stars known as the Bucket asterism, found beneath Polaris, was considered to be the Saptarisha – the seven wise men who were believed to have been born from the mind of Brahma and served as the forefathers of the current era (Kali-yuga) and all beings within it.

Greece’s “Ursa Major.”

Ursa Major is one of the 48 constellations listed in Ptolemy’s star catalog around 140 BC, although it is first mentioned much earlier, as far back as Homer. Confusing Greek myths offer different backstories of its appearance, although all agree that the bear is the beautiful Callisto, the companion of the goddess-hunter Artemis. According to one version, employing his usual tricks with reincarnation, the amorous Zeus seduced her, causing the anger of his wife Hera and Artemis herself. Saving his mistress, the thunderer transformed her into a bear, who roamed for many years in the mountain forests until her own son, born of Zeus, encountered her on a hunt. The supreme god had to step in once again. Preventing maternal murder, he brought both of them to the heavens.

America’s Majestic Bear

The Native Americans seemed to have a deep understanding of the natural world, as evident in the Iroquois legend that tells the story of the creation of a constellation known as the “celestial bear”. Interestingly, this bear is depicted without a tail. According to the legend, the three stars that form the handle of the Ladle represent three hunters who are in pursuit of the mighty beast: Aliot is shown drawing a bow with an arrow firmly embedded in it, Mitzar carries a cauldron for cooking the meat of the bear (Alkor), and Benetnash carries a bundle of kindling to light the hearth. As autumn arrives and the Ladle slowly descends towards the horizon, drops of blood from the wounded bear fall, creating a beautiful mosaic of colors on the surrounding trees.

This article focuses on the constellation itself. If you are looking for information about a group of stars that form a distinctive shape (asterism), please refer to the Big Dipper. For other meanings and interpretations, please see Big Dipper (meaning).

The constellation known as the Big Dipper ( / ˈ ɜːr s ə m eɪ dʒ ər / , also referred to as the Big Dipper ) is located in the northern sky and is believed to have origins in ancient times. Its Latin name translates to “big (or greater) bear,” as it is larger in size compared to its neighbor, the Little Bear. The constellation was one of the original 48 constellations recognized by Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD, based on the observations of Greek, Egyptian, Babylonian, and Assyrian astronomers. Today, it is considered the third largest constellation among the 88 modern constellations.

Early mentions of the Big Dipper can be found in Isidore of Seville’s “Etymologies,” specifically in Book 3, which is preserved at Corpus Christi College. Isidore describes Arcturus, the brightest star in the Volopassus constellation, as being situated “behind the tail of the Big Dipper.” Isidore, an astronomer, referred to the Big Dipper constellation as a wagon due to its wheel-like rotation and called it Septentriones, meaning “seven oxen,” which is synonymous with Septentrional. During that time, there wasn’t much distinction linguistically between oxen, sus, and a bear, ursus. It’s worth noting that the Greeks and Romans had limited exposure to bears during this period since they primarily resided in more northern regions. The Latin word ursus and the Greek word arktas share the same pronunciation and have the same Proto-Indo-European roots as the word bear. Isidore collected folklore from various sources, including travelers and philosophers. This is evident in his Bestiary, where he presents dragons, sirens, and “Draco” as factual creatures. It’s plausible that Isidore personally encountered a bear in 560 AD. In his book, he attributes the depiction of constellations in the form of bears, crabs, and other animals in the Greek zodiac to the Greeks, whom he refers to as pagans.

The Big Dipper, along with the constellations that make up its shape, holds great significance in various cultures around the world, often representing the north. The modern flag of Alaska incorporates this celestial formation as a symbol.

The Big Dipper can be seen year-round from most parts of the northern hemisphere and remains visible throughout the night for mid-northern latitudes. While the main constellation may not be visible from southern temperate latitudes, its southern components can still be observed.

- 1 Characteristics

- 2 Features

- 2.1 Constellations

- 2.2 Other stars

- 2.3 Deep space objects

- 2.4 Meteor showers

- 2.5 Extrasolar planets

- 4.1 Greco-Roman tradition

- 4.2 Hindu tradition

- 4.3 Judeo-Christian tradition

- 4.4 East Asian traditions

- 4.5 Traditions of the Native Americans

- 4.6 Traditions of Northern Europeans

- 4.7 Traditions of Southeast Asians

- 4.8 Knowledge of the Esoteric

Distinctive Features

The Big Dipper occupies an area of 1,279.66 square degrees, which corresponds to 3.10% of the entire celestial sphere, making it the third largest constellation. In 1930, Eugène Delport established the official boundaries of the constellation for the International Astronomical Union (IAU), defining it as a 28-sided irregular polygon. In the equatorial coordinate system, the constellation extends between right ascension coordinates of 08 h 08.3 m and 14 h 29.0 m, and declination coordinates of +28.30° and +73.14°. The Big Dipper is surrounded by eight other constellations: Draco to the north and northeast, Boötes to the east, Canes Venatici to the east and southeast, Coma Berenices to the southeast, Leo and Leo Minor to the south, Lynx to the southwest, and Camelopardalis to the northwest. The three-letter abbreviation for the constellation, “UMa,” was adopted by the IAU in 1922.

Functions

Asterisms

The arrangement of the seven prominent stars in the constellation of Ursa Major creates a recognizable pattern called the “Big Dipper” in the United States and Canada, while it is referred to as the “Plow” or “Charles’s cart” in the United Kingdom. Out of the seven stars, six are of second magnitude or higher, making it one of the most well-known formations in the night sky. Its shape is often likened to a bucket, agricultural plow, or wagon, which is why it is commonly depicted as the back and tail of the Big Dipper. Starting from the “bucket” part and moving clockwise (eastward in the sky) across the handle, the stars are as follows:

- α of the Big Dipper, which is also called Dubhe in Arabic (meaning “bear”), is the 35th brightest star in the sky with a magnitude of 1.79 and is the second brightest among the Big Dipper.

- β of the Big Dipper, known as Merak (meaning “loins of the bear”), has a magnitude of 2.37.

- γ of the Big Dipper, also referred to as Fekda, has a magnitude of 2.44.

- δ Ursae Majoris, or Megrez, is located at the intersection of the body and tail of the bear (or the dipper and the handle of the dipper), and its name means “root of the tail.” It has a magnitude of unknown.

- Mizar is the second star from the end of the arm of the Big Dipper and the fourth brightest star of the constellation. Mizar, which means “belt”, forms a famous double star with its optical companion Alcor (80 of the Big Dipper), which the Arabs called “horse and rider”.

- Alkaid is known as the “end of the tail” of the Big Dipper. Alkaid, with a magnitude of 1.85, is the third brightest star in the Big Dipper.

Except for Dubhe and Alkaid, all the stars of the Big Dipper have their own movement towards a common point in Sagittarius. Several other stars have been identified with similar movement, and they are collectively known as the Moving Group of the Big Dipper.

The two stars, Merak (β) and Dubhe (α), in the constellation of the Big Dipper are commonly referred to as “pointer stars” due to their ability to guide us to Polaris, also known as the North Star. By following a line from Merak to Dubhe (1 unit) and extending it for 5 units, we can accurately locate Polaris and determine true north.

Additional celestial bodies

There is another group of stars called the “Three Leaps of the Gazelle” that has significance in Arabic culture. This group consists of three pairs of stars located along the southern edge of the constellation. Moving from southeast to southwest, the first pair includes the stars ν and ξ of the Big Dipper (known as Alula Borealis and Australis, respectively). The second pair includes the stars λ and μ of the Big Dipper (known as Tania Borealis and Australis). Lastly, the third pair includes the stars ι and κ of the Big Dipper (known as Talitha Borealis and Australis, respectively).

To the west of the Big Dipper, there is a class of variable stars known as contact double stars, which range in size from 7.75 m to 8.48 m.

47 Big Dipper is a star similar to our sun and it has a system of three planets. The first planet, 47 Big Dipper b, was discovered in 1996. It takes 1078 days for this planet to complete one rotation on its axis and it is 2.53 times the mass of Jupiter. The second planet, 47 Big Dipper c, was discovered in 2001. It takes 2391 days for this planet to complete one rotation on its axis and it is 0.54 times the mass of Jupiter. The third planet, 47 Ursae Majoris d, was discovered in 2010. The period of revolution for this planet is between 8907 and 19097 days and it is 1.64 times the mass of Jupiter. The star itself has a stellar magnitude of 5.0 and it is located about 46 light-years away from Earth.

The star TYC 3429-697-1 (9h 40m 44s 48° 14′ 2″), which is situated to the east of θ of the Big Dipper and southwest of the “Big Dipper”, is officially recognized as the state star of Delaware and is informally referred to as the Delaware Diamond.

Objects in the Vastness of Space

The constellation Ursa Major contains a number of brilliant galaxies, including the duo Messier 81 (one of the most luminous galaxies in the celestial sphere) and Messier 82 positioned above the bear’s head. Additionally, the spiral galaxy M101, also known as the Pinwheel Galaxy, is situated to the northeast of eta in Ursa Major. Two other spiral galaxies, Messier 108 and Messier 109, can also be found within this constellation. The prominent planetary nebula M97, also known as the Owl Nebula, can be observed near the bottom of the Big Dipper’s bowl.

M81 is an almost edge-on spiral galaxy located approximately 11.8 million light-years away from Earth. Similar to most spiral galaxies, it possesses a central region composed of aged stars and spiral arms filled with youthful stars and nebulae. Alongside M82, it forms part of the galaxy cluster that is closest to the Local Group.

M97, also known as the Owl Nebula, is a planetary nebula situated 1,630 light-years away from our planet. It has a magnitude of approximately 10. The nebula’s discovery can be credited to Pierre Mechene in the year 1781.

M101, also referred to as the Spiral galaxy, is an inclined spiral galaxy positioned 25 million light-years away from Earth. It was first observed by Pierre Mechene in 1781. The galaxy’s spiral arms contain regions with active star formation and emit strong ultraviolet radiation. With an integrated stellar magnitude of 7.5, M101 can be seen through binoculars and telescopes, but not with the naked eye.

NGC 2787 is a lenticular galaxy that is situated 24 million light-years away. Unlike most lenticular galaxies, NGC 2787 has a central cusp. Additionally, it possesses a halo of globular clusters, which is an indicator of its age and relative stability.

NGC 2950 is a lenticular galaxy located at a distance of 60 million light-years from Earth.

NGC 3079, situated 52 million light-years away from our planet, is a spiral galaxy that is currently experiencing a surge in the birth of stars. At its core, there is a distinctive horseshoe-shaped structure, which is a telltale sign of the presence of an immensely massive black hole. This structure is actually formed by the powerful superwind emanating from the black hole.

NGC 3310, another spiral galaxy positioned 50 million light-years away from Earth, is also going through a period of intense star formation. Its remarkable bright white color can be attributed to an unusually high rate of star birth, which started around 100 million years ago after a cosmic merger event. Recent studies on NGC 3310 and similar starburst galaxies have revealed that their star formation phase can endure for hundreds of millions of years, significantly longer than previously believed.

Located 55 million light-years away, NGC 4013 is a spiral galaxy that can be observed from its edge. It boasts a striking streak of dust and several clearly visible regions where new stars are being born.

The young dwarf galaxy I Zwicky 18, located 45 million light-years away, is a unique celestial object. It holds the distinction of being the youngest known galaxy in the visible Universe, with an age of approximately 4 million years, making it just a fraction of the age of our solar system. This vibrant galaxy is teeming with active star-forming regions, where numerous hot, young, blue stars are born at an astonishing rate.

Meteor shower

The Bear’s Kappa Majorids is a newly discovered meteor shower that reaches its peak between November 1 and November 10.

Extrasolar planets

HD 80606, a star similar to our Sun, is part of a binary system where it revolves around a common center of gravity with its companion, HD 80607. These two stars have an average separation of 1200 astronomical units. Studies conducted in 2003 indicate that HD 80606 b, the only known planet in this system, is a future hot Jupiter that initially formed in a perpendicular orbit about 5 astronomical units away from its star. It is predicted that this planet, with a mass four times that of Jupiter, will eventually transition to a more circular and aligned orbit using the Kozai mechanism. However, at present, it follows an extremely eccentric orbit, ranging from approximately one astronomical unit at its farthest point from the star (apoapsis) to six times the radius of the star (periapsis).

The Background

The constellation known as the Great Bear has been reconstructed as an ancient Indo-European group of stars. It was one of the 48 constellations originally identified by the astronomer Ptolemy in his famous work, the Almagest. Ptolemy referred to this constellation as Arktos Megale. Throughout history, the Big Dipper has been mentioned in the works of various poets including Homer, Spenser, Shakespeare, Tennyson, and Federico Garcia Lorca in his poem “Song for the Moon”. It is also referenced in ancient Finnish poetry and even portrayed in Vincent Van Gogh’s famous painting “Starry Night Over Rona”. Some scholars suggest that the Big Dipper may also be mentioned in the biblical book of Job, although this interpretation is a subject of debate among experts.

The Big Dipper constellation has been associated with various civilizations as a representation of a bear, typically depicted as a female. This belief may have originated from a shared oral tradition of Cosmic Hunt myths that can be traced back more than 13,000 years. Julien d’Huy uses statistical and phylogenetic tools to recreate the following ancient narrative: “There exists a horned herbivorous creature, specifically an elk. A single individual chases after this hoofed animal, leading the pursuit to the heavens. The creature transforms into a constellation, coming to life as it forms the Big Dipper.”

The Greco-Roman Mythology

According to the ancient Roman mythology, Jupiter, who was the king of the gods, developed a strong desire for a young woman named Callisto, who was a nymph in the service of Diana. However, Juno, Jupiter’s jealous wife, discovered that Callisto had a son named Arcas and suspected that he was fathered by Jupiter. In her anger and jealousy, Juno decided to punish Callisto by transforming her into a bear, hoping that this would end her attraction to Jupiter. As a bear, Callisto later encountered her son Arcas. Seeing the bear, Arcas almost shot it, but to prevent a tragic mistake, Jupiter intervened and transformed Arcas into a bear as well. The two bears were then placed in the sky as constellations, forming what is now known as the Big Dipper and Little Dipper. Callisto became the Big Dipper, while her son Arcas became the Little Dipper. In an alternate version of the story, Arcas was transformed into the constellation of Volopas.

During ancient times, the constellation was known as Helike due to its revolving motion around the pole. In the second book of Lucan, it is referred to as Parrasian Helike, named after Callisto who hailed from Parresia in Arcadia, the setting of the story. The Odyssey mentions that this constellation never dips below the horizon and “immerses itself in the waves of the Ocean”, making it a crucial celestial marker for navigation. It is also commonly referred to as the “Vein”.

Hindu tradition

The Hindu religion has a unique understanding of the Big Dipper, also known as the Big Bear or Saptarshis. In this tradition, each of the stars in the constellation represents one of the Saptarishi or Seven Sages, namely Bhrigu, Atri, Angiras, Vasishtha, Pulasthya, Pulaha, and Kratu. The interesting alignment of the two front stars of the Big Dipper pointing towards the polar star is attributed to a special gift bestowed upon the young sage Dhruva by Lord Vishnu.

The Judeo-Christian heritage

Referenced in several biblical passages (Job 9:9; 38:32; Orion and the Pleiades and others), the Big Dipper was symbolically represented as a bear by the Jewish community. The term “bear” was translated as “Arcturus” in the Vulgate and is still present in the King James Version of the Bible.

East Asian customs

The “Northern Dipper” 北斗 (Chinese: běidǒu, Japanese: hokuto) is the term used for the Big Dipper in China and Japan. In ancient times, each of the seven stars had its own unique name, often derived from ancient China:

- Dubhe (Alpha of the Big Dipper) is known as the “Pivot” 樞 (C: shū, J: sū).

- Merak (Beta of the Big Dipper) is referred to as “Beautiful jade” 璇 (C: xuán, J: sen).

- Fekda (Gamma of the Big Dipper) is called “Pearl” 璣 (C: jī, J: ki).

- Megres (Delta of the Big Dipper) is associated with the term “Balance” 權 (C: quán, J: ken).

- Aliot (Epsilon of the Big Dipper) is known as the “Measuring ruler made of jade” 玉衡 (C: yùhéng, J: gyokkō).

- Alkaid (Eta of the Big Dipper) is known by several names: the “Sword” 劍 (C: jiàn J: ken ) (abbreviated from “Sword’s End” 劍先 (C: jiàn xiān J: ken saki )), the “Flickering Light” 搖光 (C: yáoguāng J: yōkō ), and the “Star of Military Defeat” 破軍星 (C: pójūn xīng J: hagun sei ), as it was believed to bring bad luck to the army when traveling in its direction.

In the Shinto religion, Ame-no-Minakanushi, the oldest and most powerful kami, is associated with the seven largest stars of the Big Dipper.

In South Korea, the group of stars is referred to as “the northern seven stars”. In a connected legend, a widow with seven sons sought solace at the home of a widower, but had to cross a river to reach his house. The seven sons, understanding their mother’s plight, placed stepping stones in the river. Unaware of who had placed the stones, their mother bestowed her blessings upon them, and upon their passing, they transformed into a constellation.

Indigenous American Customs

The Iroquois people saw Aliot, Mitsar, and Alkaid as a trio of hunters chasing after the Big Dipper. As per one rendition of their folklore, the initial hunter (Aliot) wields a bow and arrow to hunt down the bear. The second hunter (Mitzar) carries a large pot, represented by the star Alcor, on his shoulder to cook the bear, while the third hunter (Alkaid) carries a stack of firewood to light a fire beneath the pot.

The Lakota tribe refers to the Big Dipper as Wichahiyuhapi, or the “Big Dipper”.

The Wampanoag (Algonquin) people referred to the Big Dipper as “mask”, which means “bear”, according to Thomas Morton in his work “New England Canaan”.

The Indigenous Americans of Wasco-Wishram interpreted the constellation as the five wolves and two bears that were left in the sky by Coyote.

Nordic Customs

In the Finnish language, the group of stars known as the Big Dipper is sometimes called Otava. The significance of this name has been largely forgotten in modern Finnish, but it originally meant “salmon dam.” According to ancient Finnish beliefs, the bear (Ursus arctos) was brought to Earth in a golden basket from the Big Dipper. After the bear was slain, its head would be placed on a tree, allowing the bear’s spirit to return to the Big Dipper.

In the languages of the Northern European Sami, a portion of the constellation (specifically, the Big Dipper without Dubhe and Merak) is recognized as the bow of the renowned hunter Favdn (the star Arcturus). In the primary Sami language, Northern Sami, it is called Favdnadavgi (“Favdna’s Bow”) or simply dávggát (“Bow”). This constellation holds significant importance in the Sami national anthem, which commences with the phrase Guhkkin davvin davggaid vuolde sabmá suolggai Sámi eanan, meaning “Far to the north, under the Bow, the land of the Sami slowly comes into view”. The Bow plays a crucial role in the traditional Sami folklore of the night sky, where various hunters endeavor to chase the Sarva. According to legend, Favdna is prepared to shoot his bow every night, but hesitates out of fear of striking Stella Polaris, also known as the Stella Polaris. This would result in the collapse of the sky and the end of the world.

Southeast Asian Customs

In the Burmese culture, there is a constellation called Pucwan Tārā (ပုဇွန် တာရာ, pronounced “bazun taya”) that consists of stars located on the head and forelegs of the Big Dipper. The term pucwan (ပုဇွန်) is a general term used to describe crustaceans such as shrimp, prawns, crabs, lobsters, and other similar creatures.

In Javanese tradition, this constellation is referred to as “lintang jong,” which translates to “jong constellation.” Similarly, in the Malay language, it is known as “bintang jong.”

Theosophy holds the belief that the spiritual energy of the seven rays from the Galactic Logos is focused by the Seven Stars of Pleiades, then passed on to the Seven Stars of the Big Dipper, then to Sirius, then to the Sun, then to the Earth God (Sanat Kumara), and ultimately transmitted through the Seven Gurus of the Seven Rays to the human race.

Graphic visualization

European star charts depicted the constellation by using the “square” shape of the Big Dipper, which created the body of a bear. Additionally, a chain of stars formed the “handle” of the Dipper, resembling a long tail. It is worth noting that bears do not have long tails. On the other hand, Jewish astronomers interpreted Aliot, Mitsar, and Alkaid as three bear cubs following their mother, while Native Americans saw them as three hunters.

You might say that the alternate asterism HA Rey for the Big Dipper provides it with the extended head and neck of a polar bear, as observed in this picture from the left on the left side.

The well-known author of children’s books, H. A. Rey, had a different asterism in mind for the Big Dipper in his 1952 book “Stars: a new way to see them” (ISBN 0-395-24830-2). In his version, the Big Dipper formed the outline of a “bear” constellation with Alkaid as the bear’s nose and the handle portion of the Big Dipper forming the outline of the bear’s head, neck, and back toward the shoulder, potentially giving it a longer polar bear head and neck.

The Big Dipper, as shown in The Mirror of Urania, a collection of star maps published in London circa 1825.

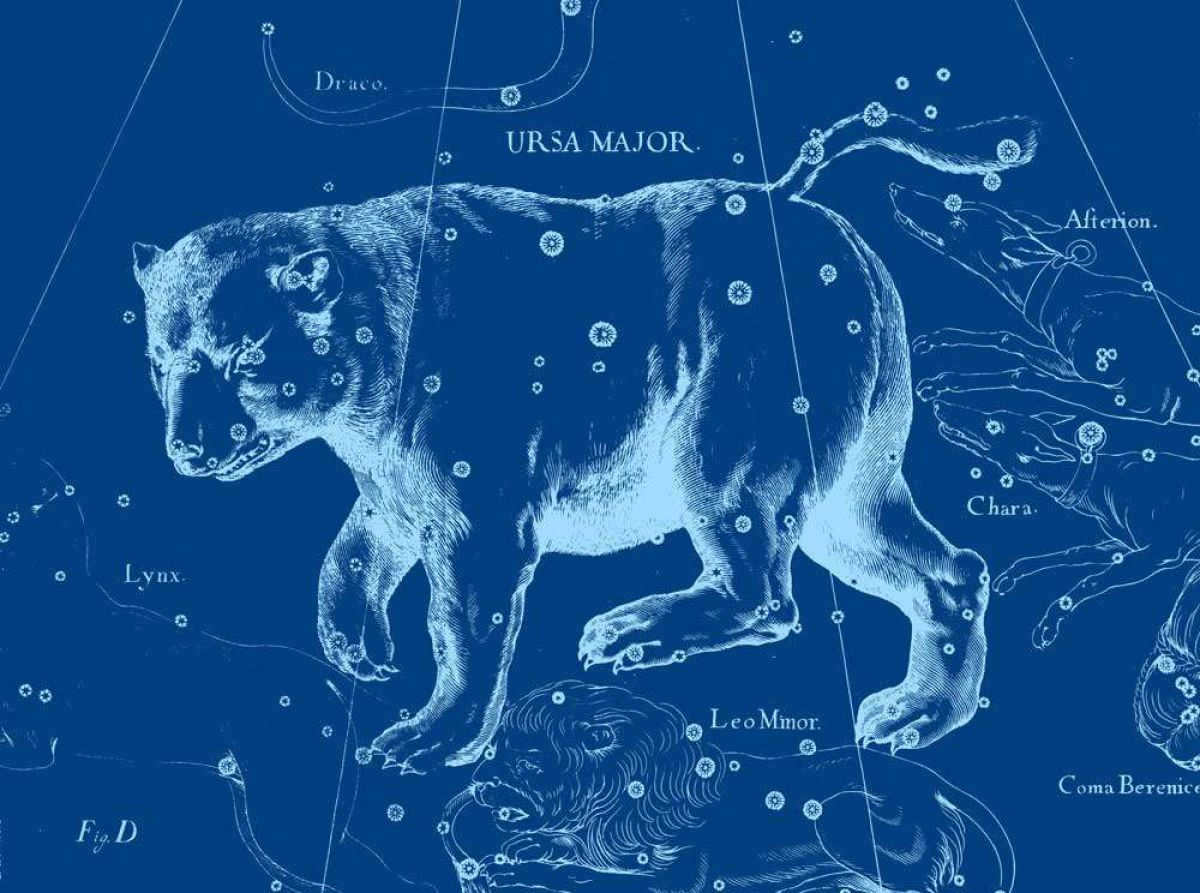

Johannes Hevelius depicted the Big Dipper as if it were observed from outside the celestial sphere.

The Big Dipper is also represented as the Star Plow, the Irish labor flag adopted by James Connolly’s Irish Citizen Army in 1916, which displays the constellation on a blue background; on the national flag of Alaska; and on a variation of the coat of arms of Sweden created by the House of Bernadotte. The seven stars on the red background of the flag of the Community of Madrid, Spain, might represent the stars of the asterism of the Plough (or Little Bear). The same can be said of the seven stars on the azure border of the coat of arms of Madrid, the capital of that country.

Check out these related articles

- Big Dipper in Chinese astronomy

- Little Bear constellation

- The Southern Cross

- Celestial cartography and its significance

- Exploring the family of constellations

- Former constellations and their history

- Lists of stars organized by constellation

- Constellations catalogued by Johannes Hevelius

- Constellations recorded by Lacaille

- Constellations listed by Petrus Plancius

- Ptolemy’s catalog of constellations

References

- Levy, David H. (2005). Objects of deep space. Prometheus books. ISBN978-1-59102-361-6.

- Thompson, Robert; Thompson, Barbara (2007). An illustrated guide to astronomical wonders: from beginner to master observer. O’Reilly Media, Inc. ISBN978-0-596-52685-6.