A simple method to navigate the stars is by locating Polaris. It is not only one of the brightest, but also remains stationary in its position. There are two well-known techniques that can be used to accurately locate Polaris.

The constellation of Ursa Major and Ursa Minor

These star formations are depicted as a large and small ladle. To identify the main reference point using the stars, you must follow these steps:

- Mentally connect the outermost stars of the Ursa Major’s ladle wall;

- Extend the imaginary line to the outermost star on the handle of Ursa Minor’s ladle;

- If the distance between the constellations is equal to five times the size of Ursa Major’s ladle wall, then the reference point is accurately determined.

By observing Polaris, an individual will always move towards the north, consequently, the south will be behind their back.

Cassiopeia

During the nighttime, it is easy to observe the constellation Cassiopeia, which is represented by the letter W. Polaris, also known as the North Star, is situated along the line connecting the lower left point of the letter W and the second star on the handle of the Big Dipper. This point of reference can be found approximately in the middle of the line where it intersects with the constellation Ursa Minor, also known as the Little Bear.

The location of the Orion constellation from the Big and Little Bears

Cassiopeia

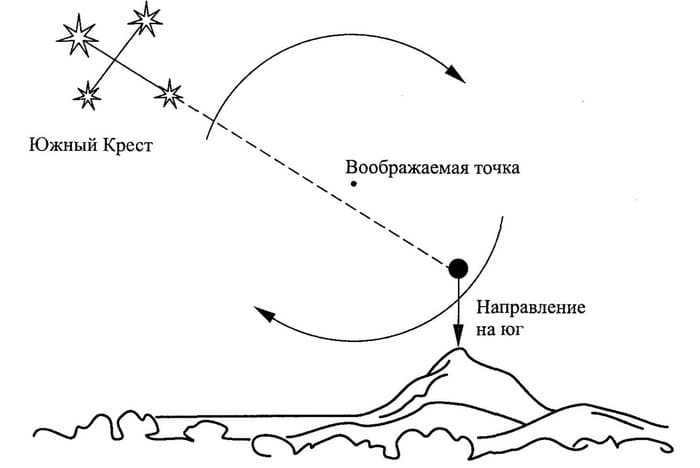

In the southern hemisphere near the Southern Cross

When in the southern hemisphere, you can find your way by looking for the constellation Southern Cross. The well-known Polaris cannot be seen from this part of the world.

The cross is made up of four bright stars. It is crucial not to mistake this constellation for the False Cross, which is located to the right. The stars in the False Cross are not as bright and are spread out further.

To determine the direction south, you need to mentally draw a line connecting two stars that are opposite each other. This will create two intersecting lines, with the longer one pointing south.

Discovering Direction with the Southern Cross

From Ancient Times to the 16th Century

The ancient practice of dividing the night sky into constellations was embraced by European culture. Ptolemy’s catalog of constellations served as the foundation for the widely used star charts in Europe.

The influential ancient scientist Claudius Ptolemy, who lived in the 2nd century AD, had a significant impact on the development of astronomy during the Middle Ages. His important work, known in Europe as “The Great Mathematical Structure” but distortedly called “Almagest” in Arabic, serves as an encyclopedia of the accomplishments of ancient astronomy (Earth and Universe, 1999, No. 2). Within the Almagest, there is the earliest surviving record of fixed stars, featuring the same constellations as those described by the poet Aratus in the 3rd century BC. Aratus’ poem Phenomena, a remarkable piece of Hellenistic poetry, holds great historical significance in the field of ancient astronomy as it provides the earliest complete description of the sky (Earth and Universe, 1998, no. 3).

Ptolemy’s catalog utilized the technique of identifying stars based on their position within a constellation (or relative to other stars), which was the primary means of identification before the development of universal celestial coordinate systems. For instance, a star might be described as “located on the head of the leading twin” or “situated on the knee of the left leg of the trailing twin.” The Almagest star catalog served as the foundation for the tradition of catalogs and celestial maps in Western Europe.

In 1515, the artist A. Dürer (1471-1528) published the first printed depictions of the constellations. Assisting him in this endeavor were two astronomers, Johann Stabius and Konrad Heinfonel. It is worth noting that Dürer’s star charts were presented in a mirrored fashion, depicting the sky as it would appear “from the outside” on a star globe.

The list of 88 constellations that was approved by the First ICA Congress in 1922 includes all 48 constellations listed in Ptolemy’s catalog. It also includes the asterism “Hair” mentioned by him, which later became the constellation “Veronica’s Hair”. It is worth noting that an asterism is a broader and older term than a constellation, although in most cases it can be referred to as an asterism. An asterism can be any remarkable object or group of objects in the sky.

The next stage in refining the structure of the modern star map took place in 1595, when the Dutch added 12 new constellations to a map of the southern sky that were not visible from the middle latitudes of the northern hemisphere. These constellations filled an area in the southern hemisphere of the sky that was unknown to ancient astronomers.

In addition to the twelve constellations already known, three additional constellations – the giraffe, the dove, and the unicorn – were discovered by P. Planzius in 1598. These newly found constellations served to occupy the areas of the sky that lacked prominent stars and filled in the gaps between existing constellations.

By 1603, E. Bayer’s Uranometria was published, featuring 48 maps of the Ptolemaic constellations and a separate map of the southern sky showcasing twelve new constellations.

Another significant alteration to the constellation structure took place in 1690 with the publication of J. Hevelius’ “Description of the whole starry sky, or Uranography.” Hevelius introduced seven new constellations that filled both large sections (such as the hunting dogs) and smaller areas (like the Lizard constellation) that lacked prominent stars.

The organization of the southern sky into constellations was finished in 1751-52 through the efforts of N. Lacaille. His chart of the southern sky was published in Paris in 1763.

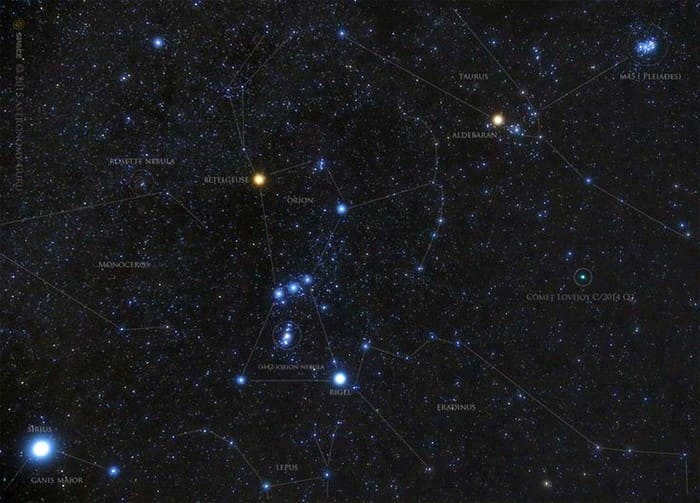

Navigation using the constellation Orion

The constellation known as Orion is visible from any location on the planet, making it a useful tool for determining direction in both the northern and southern hemispheres, but only during the winter months.

Orion is comprised of 7 stars and has the shape of an hourglass. In the middle, 3 stars form what is commonly referred to as Orion’s Belt. At sunrise, the rightmost point of the Belt points towards the east, while at sunset it points towards the west.

The star constellation Orion

The origin of the starry sky map

Throughout history, humans have gazed up at the mesmerizing night sky, adorned with countless twinkling stars. It is likely that even early “astronomers” tried to comprehend what they were witnessing and discovered that most stars belong to fixed groups that can shift in the sky and temporarily disappear behind the horizon, only to reappear in their original positions. These groups were given names, often inspired by animals, mythical creatures, legendary heroes, and even everyday objects. Various cultures developed their own unique naming systems. For instance, ancient Chinese scientists named star clusters after imperial palaces and their rooms. However, the names we are familiar with for the 48 constellations visible in the night sky of the Northern Hemisphere are predominantly derived from the ancient cultures of Europe and the Middle East. Since the 16th century, an additional 40 star groups have been identified, but they are mostly visible only in the Southern Hemisphere, so the ancient Greeks, Romans, and Arabs were unaware of them.

Therefore, at present, there are a total of 88 constellations defined and officially recognized by the International Astronomical Union on the celestial sphere of the world.

Determining latitude

Thanks to the celestial bodies, seasoned travelers have the ability to determine their latitude even during nighttime. In order to accomplish this, the following steps must be taken:

- Locate Polaris.

- Any method can be used to find it, such as observing the constellations of the Bears or Cassiopeia.

- Measure the angle between Polaris and the horizon.

There are two possible scenarios in this case:

- To accurately determine the measurement of this angle, it is advisable to utilize specialized instruments. By employing a quadrant and sextant, one can ascertain the angle displayed on the curved surface of the device. This angle corresponds to the latitude value north of the equator.

- An approximate estimation of the angle can also be made without the aid of navigational tools. Simply extend your arm towards the horizon and progressively stack one closed fist on top of the other. Repeat this action until the North Star is reached. Each outstretched arm with a closed fist represents an approximate measurement of 10 degrees.

Constellation Placement

Knowing the positions of constellations can greatly assist a traveler in determining directions and navigating their way, particularly on a cloudless evening. As such, it is crucial for novices to grasp how the stars shift their positions throughout the night and across the different months of the year. Various constellations are more easily identifiable during specific times of the year.

Did you know? Memorizing all the constellations at once can be challenging, but it’s not necessary. You only need to remember a few key constellations to find the south at midnight, such as the Great and Little Dog, Leo the Lion, the Wolopassus, Taurus, and Orion. Another helpful guide is the Milky Way, which stretches from the south to the north.

Constellations

Constellations are divisions of the celestial sphere used in modern astronomy to facilitate navigation in the night sky. These areas are formed by grouping together bright stars and were historically represented as distinct figures.

Despite appearing close to each other on the celestial sphere, the stars within constellations can be widely separated in three-dimensional space. Throughout history, people have recognized patterns and relationships among the stars, organizing them into constellations based on these observations.

Over the course of history, there have been various constellations and their outlines identified by observers, and the origins of certain ancient constellations remain a mystery. Prior to the 19th century, constellations were not confined to specific areas of the sky, but rather constituted groups of stars that often overlapped. It was discovered that some stars belonged to multiple constellations simultaneously, while certain star-poor regions did not belong to any constellation. In the early 19th century, boundaries were established between constellations, eliminating the “void” between them, although these boundaries were still not clearly defined and were subject to individual interpretation by different astronomers.

The first General Assembly of the International Astronomical Union made the decision to approve a list of 88 constellations in Rome in 1922. These constellations were divided in the starry sky, and in 1928, clear and unambiguous boundaries were adopted for each constellation. These boundaries were determined by following the circles of direct ascents and descents of the equatorial coordinate system of 1875.0. Over the course of five years, the boundaries of the constellations were refined. In 1935, the boundaries were finalized and have remained unchanged since then. It is important to note that due to the precession of the Earth’s axis, the boundaries of the constellations no longer align with the circles of direct ascension and descent on star charts drawn for eras other than 1875.0, especially on modern charts.

The signs of the zodiac, traditionally known as the 12 constellations, are the ones that the sun passes through (except for the Serpent Bearers constellation).

A Universal Method Using Pegs

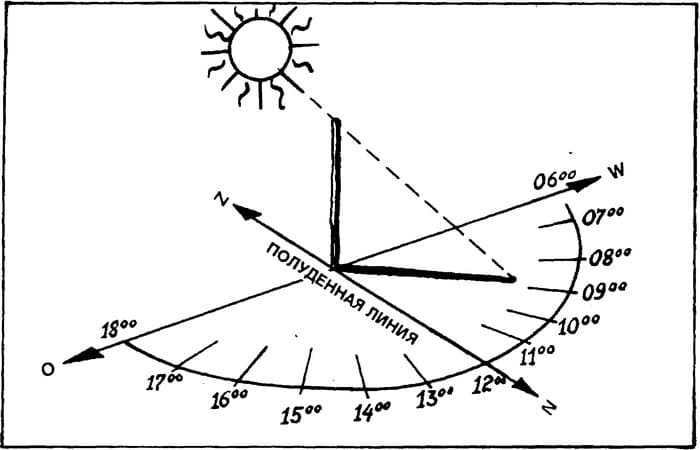

Daytime Orienteering

One can also navigate through the terrain using the Sun. It serves as an excellent landmark that maintains a consistent trajectory throughout the day. Additionally, unfavorable weather conditions rarely obstruct the view of this celestial body.

Orienteering based on the Sun’s position relies on two fundamental principles. Firstly, in the southern hemisphere, a traveler can determine north by looking at the Sun at noon. Conversely, in the northern hemisphere, south can be determined at this time. Secondly, the east is always where the sunrise occurs, and the west is where the sunset takes place.

Orientation using pegs

The process of orientation using pegs is as follows:

- To begin, a long stick or peg should be driven into the ground, preferably on a flat surface. This should create a clear shadow.

- Next, the top of the shadow cast by the object is marked.

- A second mark is made at least 30 minutes later, when the shadow has changed its original position.

- By connecting the two marks, the east-west direction can be determined. In this case, the first mark indicates the west, while the second mark indicates the east.

- To determine the location of the north, one must face a particular line and place the toe of the left foot on the first point while the right foot rests on the second mark. The north is in front, with the north-south direction perpendicular to the drawn line.

Navigation in cloudy conditions

Occasionally, weather conditions make it challenging to navigate using the Sun due to dense black clouds. However, if the rest of the sky is less cloudy, it is still possible to determine the direction of travel with an error margin of 10-20 degrees.

In cloudy weather, the methods involving pegs can still be employed since the clouds do not hinder the observation of the Sun’s shadow. Alternatively, some adventurers opt for the second method of orienteering by the Sun, which is as follows:

- During the morning, the highest point of the shadow cast by the peg is marked, and its length is measured;

- In the afternoon, another marking is made at the top when the shadow reaches the same length as it did during the first marking;

- The two points are then connected by a straight line, which serves as an indicator of the north-south direction.

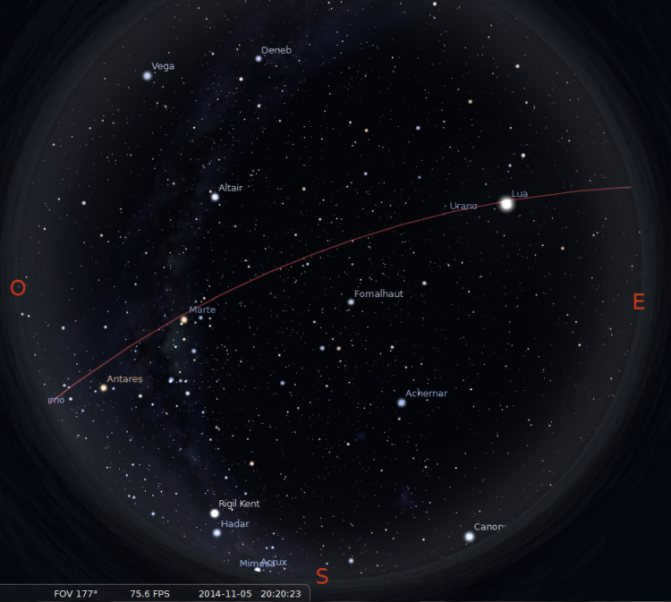

Nighttime Orienteering

If a traveler finds themselves lost in the wilderness, they can devise a new route regardless of their location on Earth’s continents. One such method involves using the constellation Orion, which can be seen in both the northern and southern hemispheres. However, if desired, any other star can be chosen to employ this universal technique.

Orienteering at night using pegs is a unique method that can be used to navigate by celestial bodies.

This method involves digging pegs into the ground, spaced 1 meter apart, with the chosen celestial body in the same plane as the pegs.

- To begin, observe the movement of the star for a certain period of time.

- If the star rises above the imaginary line between the pegs, it indicates that the line is pointing east. Conversely, if the star moves slightly downward, it means the line is pointing west.

- If the star moves to the right, it indicates the southern side, while movement to the left indicates the northern side.

- However, if the bright star is displaced at an angle, this method becomes more complex and requires additional calculations, which can take more time.

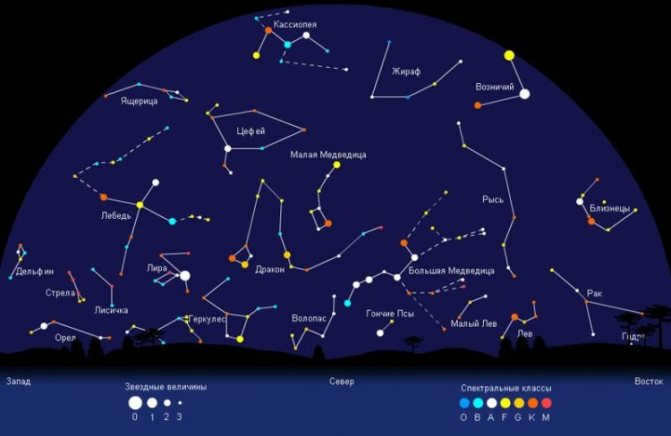

Constellations in the Northern Subpolar Region

Similar to the Moon, the constellations traverse the night sky from east to west. This is because the Earth rotates on its axis in a westward direction. The constellations found within 40 degrees of the North Pole are part of the North Subpolar Region. These constellations are always visible throughout the year and never disappear below the horizon. The North Subpolar Region is home to five prominent circumpolar constellations: Cassiopeia, Cepheus, the Big Dipper, the Little Dipper, and the Dragon. The Dragon constellation is a series of stars that spans a large portion of the sky. Its tail lies between Polaris and the Big Dipper, its body wraps around the Little Dipper and Cepheus, and its head points towards the Hercules constellation.

Triangle of Stars in the Summer Sky of the Northern Hemisphere

In the warm summer nights of the Northern Hemisphere sky, there is a cluster of stars known as the Summer Triangle. This celestial formation consists of three of the most brilliant stars found in the constellations of Lyra, Swan, and Eagle: Vega, Deneb, and Altair.

In the winter season, you can spot the Winter Triangle in the middle of the night sky. This constellation is made up of the brightest stars in Orion, which is known as Betelgeuse, as well as the Big Dog, represented by Sirius, and the Lesser Dog, known as Procyon.

During the springtime, other constellations like Leo and Virgo also showcase some of the most brilliant stars. However, some constellations that are not part of the circumpolar region may be partially hidden behind the horizon, but can still be observed in the southern hemisphere. Examples of these constellations include Orion, Taurus, the Big Dog, and Gemini.

Using Stars for Navigation at Sea

Utilizing the position of stars as a sole means of navigation on the open ocean is an incredibly challenging task. However, with the advent of modern technology, ships of all sizes now rely on satellite navigation systems that operate even in the most isolated areas far from land.

Before the invention of satellites and computers, explorers and renowned travelers were able to chart precise courses by observing natural indicators. In the past, celestial bodies such as stars, the sun, and the moon, as well as wind patterns and ocean currents, served as the primary tools for orienteering on the vast expanse of the sea.

Orienteering by the stars at sea

It wasn’t just scientists who ventured out onto the open seas. The Vikings, too, sailed the world, relying not only on calculated directions but also on their intuition and incredible attentiveness.

Fun fact: In ancient times, sailors also used sundials as a navigational aid. This allowed them to gauge their ship’s speed and find their way to land even in cloudy weather. However, these calculations were highly inaccurate.

Nowadays, ships heavily rely on GPS systems for navigation, but these systems are not immune to being hacked. Therefore, it is crucial for every sailor to be familiar with celestial navigation techniques. One can utilize stars like Polaris or the Southern Cross constellation to determine directions when at sea, depending on the hemisphere.

Having knowledge of celestial navigation can prove to be essential at any given time. It is important to keep in mind that these methods, when used without specialized tools, may contain some margin of error. However, in situations where a traveler finds themselves lost, the ability to navigate using the stars can prevent panic, assist in finding the correct course, and ultimately guide them out of unfamiliar territory.

Did you find this information helpful? Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments section!

The image of the starry night sky that can be observed on a clear, cloudless evening contains approximately 3,000 stars – a minute fraction of the 150 million star cluster within our Milky Way galaxy.

When it comes to navigation, the smallest among the many celestial bodies are the brightest stars, planets, the Sun, and the Moon.

Out of the 9 planets in our solar system, the ones visible to the naked eye are of particular interest: Venus, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn; these are commonly referred to as navigational stars.

The list of 160 navigational stars can be found in various manuals and documents, such as MAE, Navigational Tables (MT-2000), and MAL.

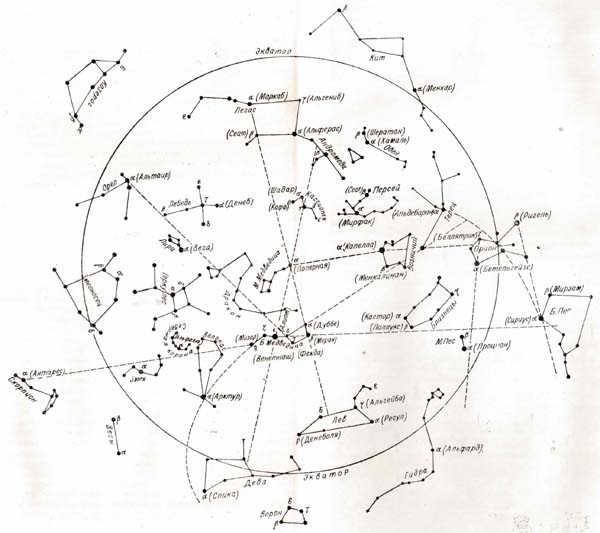

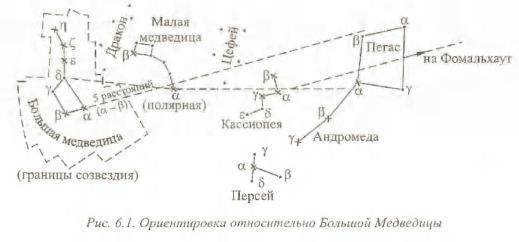

When identifying navigational stars, the first step is to observe the arrangement of constellations in which they are located. For those in northern latitudes, it is most convenient to begin by locating the well-known constellation of the Big Dipper in the northern half of the sky. This constellation resembles the shape of a bucket. To find the Little Dipper, one can draw an imaginary line connecting the outermost stars of the Big Dipper, Dubhe and Msrak, and extend it five times. The end point of this line will lead to Polaris, also known as the North Star. Polaris is located near the point of the north pole of the Earth, so its direction corresponds to the north (N), and its height above the horizon corresponds to the observer’s geographical latitude (cf) (Fig. 6.1).

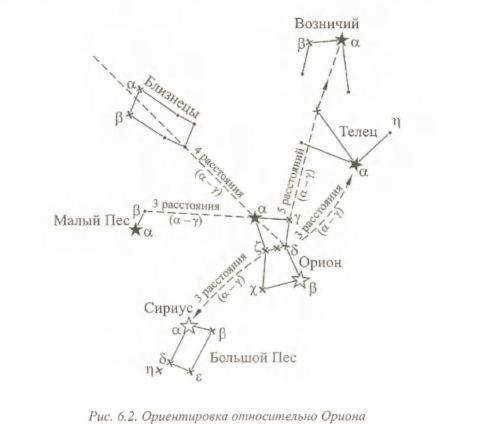

When it comes to using a reference constellation, Orion can be quite handy (Fig. 6.2).

During the onset of winter in the northwestern regions of Russia, Orion can be observed in the southern part of the sky, appearing as a robust quadrangle with a distinctive slanted belt. Positioned north of Orion are the constellations of Taurus, Ascendant, and Gemini, while to the west and southwest lie the constellations of the Lesser Dog and the Greater Dog. Among the brightest stars within these constellations are Rigel, Betelgeuse, Aldebaran, Capella, Castor, Pollux, Procyon, and Sirius.

Another crucial aspect of star recognition is the perceived brightness (luminosity) of the star. The brightness of a star is determined by its “apparent magnitude” t, which can be found in reference books. Highly luminous stars (such as Vega and Arcturus) have a luminosity of m = 0; the brightest star, Sirius, has a luminosity of m = -2. Stars with a brightness of m = 2 are six times less bright than stars with m = 0. On star maps and globes, the brightness of stars is represented by the size of their images.

Another characteristic used for star identification is their color. Stars can have the following colors: blue, white, orange, yellow, red, and dark yellow.

A star globe is a valuable tool for identifying celestial bodies.

Travelers in the modern era are fortunate to have an array of gadgets at their disposal, such as computers, cell phones, and navigators, which greatly facilitate their journeys. These devices offer a multitude of functions, including the ability to detect one’s location and create a route. However, there are instances when unforeseen circumstances arise and these gadgets fail. In such cases, especially during the night, it becomes crucial to know how to navigate without these devices. The ancient practice of orienting oneself by the stars can prove to be invaluable in such situations.

Professional pocket transportation compass Eyeskey is a forest navigator. Photo AliExpress

The essence and principle of astronavigation

Star orientation is a technique that enables you to determine your location by using celestial bodies with a consistent path. The concept behind it is that by using stars or constellations, you can calculate the main directions of the horizon and, based on that, understand the direction you need to move in. This method was developed by navigators who observed the correlation between the positions of stars and the cardinal directions. It was the only way to find the correct path while navigating on water, as there were no other landmarks available. During that time, maps were not utilized, let alone navigators.

The advantages of orienteering by the stars include:

- Reliability. Locating the stars in the night sky is one of the most consistent things in the world. With even basic knowledge of astronavigation, you can determine your location.

- Precision. Using the stars as a guide can sometimes provide more accurate coordinates than specialized devices.

- Accessibility. Star navigation does not require any additional equipment. Simply looking at the night sky is enough.

Outdoor adventure gear: compass + collapsible binoculars. Photo OZON

- Certain constellations can serve as navigational aids, but only if a person is in a specific part of the world and has a clear view of the night sky. For instance, the North Star is only visible in the northern hemisphere and cannot be seen from the middle latitudes of the southern hemisphere.

- In order to determine precise coordinates and navigate in a specific direction, extensive knowledge of stars and their paths is required. “Amateurs” can only obtain general location information.

- Weather conditions play a significant role. When the sky is covered with clouds, even the most comprehensive information about celestial bodies won’t yield any results.

Notable Features in the Nocturnal Firmament

The nocturnal expanse is adorned with a multitude of stars and constellations that can act as navigational landmarks. The tabular representation below highlights the significance of certain celestial luminaries.

| Star / constellation | Indication |

| Polaris | The most significant landmark in the night sky, Polaris indicates the direction of north. By determining its location, you can understand the orientation of the cardinal directions. |

| Southern Cross | A constellation that points towards the south. |

| Orion | A constellation that indicates the east or west direction from anywhere on Earth. |

| The Milky Way | Its path runs from north to south and can only be seen on a clear night. |

| The Big Dipper, the Little Dipper, and the constellation Cassiopeia. | Three constellations that help accurately locate Polaris and distinguish it from other bright stars or planets. |

What are the devices that can assist in celestial navigation?

In addition to modern navigational tools that handle all the technical aspects of navigation such as determining coordinates, plotting routes, and calculating travel time, there are other devices that aid in orienting oneself using the night sky. These devices are more complex to use but do not require internet access like a modern navigator. Some of these devices include:

- Compass – a device with a magnetized needle that points towards the north no matter the location. By determining the north, one can calculate the other directions.

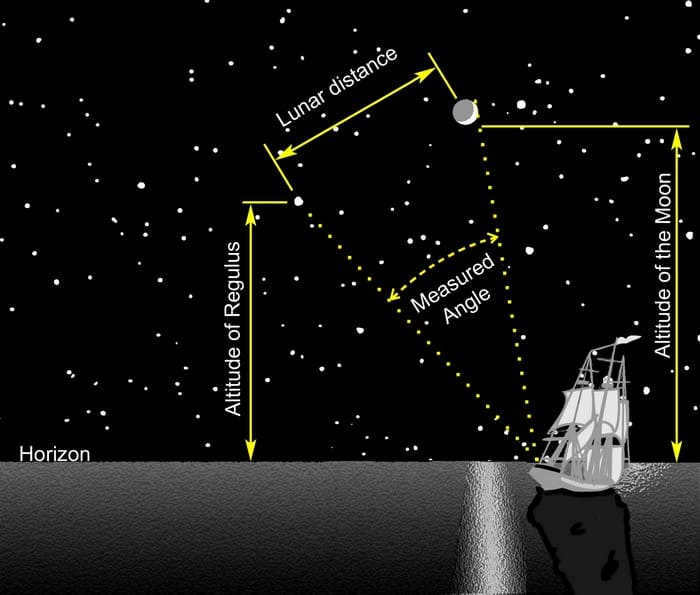

- A sextant is a device used for determining geographic coordinates. Its functioning is based on measuring the angle between a celestial body and the horizon. By knowing this angle, one can calculate either latitude or longitude, and consequently determine a person’s distance from the equator.

- A chronometer is a navigational tool that assists navigators in determining their location. It is similar to a watch but offers greater accuracy. By using a chronometer, navigators can calculate longitude, a value that was nearly impossible to determine while at sea in ancient times. Latitude, on the other hand, can be calculated by observing the position of Polaris in relation to the horizon line. By knowing both latitude and longitude, it becomes possible to pinpoint an exact location.

How to Find Your Location in the Northern Hemisphere Using the Starry Sky

There are several techniques that can be utilized to determine your location in the Northern Hemisphere.

Using Polaris

One of the simplest and most dependable methods for calculating your cardinal directions is by using Polaris, the most prominent and brightest celestial landmark in the night sky. This method is so straightforward that even schoolchildren are aware of it. Polaris always maintains its position in the sky, making it a reliable reference point. By facing towards Polaris, you can easily identify that north is directly in front of you, south is behind you, west is to your left, and east is to your right.

Many individuals often mistake it for Venus, as the planet also stands out in the nighttime sky due to its brightness. Locating Polaris is quite simple if you use the constellations known as the pointers. The most well-known ones are the Little Dipper and the Big Dipper. The Little Dipper resembles a “dipper,” with Polaris being the final star on the “handle of the bucket.” If, for some reason, the Little Dipper is not visible, you can locate its brighter counterpart, the Big Dipper.

The two outermost stars of the Big Dipper’s “bucket,” known as Merak and Dubhe, point in the direction of Polaris. The distance to Polaris is equivalent to five segments of a ray between these stars.

Exploring the Milky Way

Navigation using the Milky Way is feasible only under optimal conditions. This necessitates clear skies and minimal light pollution. The shimmering trail of the Milky Way consistently runs from the northern to the southern horizon. Armed with this knowledge, deciphering the orientation of other cardinal directions becomes a straightforward task.

The configuration of the constellation Orion, also known as the Hunter, resembles either an hourglass or a bow. Contained within this constellation are three closely spaced bright stars known as Orion’s belt. The star on the right side (Mintaka) ascends in the east and descends in the west. It is most easily observed during the chilly seasons of autumn or winter.

Discover more about navigating using various stars in this video:

Using 2 pegs

If you cannot identify any familiar constellations in the night sky, don’t worry. You can still navigate using a single star. To do this, you will need to locate two stakes and drive them into the ground about a meter apart, ensuring that the imaginary line connecting them aligns with the chosen star. All stars move from east to west, so eventually, the chosen star will also move. Once it has moved away from the line connecting the pegs, it indicates that east is in front of you. If it moves upwards, west is in front of you. Similarly, moving to the right indicates south, while moving to the left indicates north.

How to Determine Your Location in the Southern Hemisphere

When you find yourself in the Southern Hemisphere, it is important to know how to orient yourself using the Southern Cross constellation. Here are the steps you can take:

- Identify four bright stars in the sky that can form a cross when you connect them with imaginary lines. This is the Southern Cross constellation. Be careful not to mistake it for the False Cross, which is located to the right and is dimmer with greater distance between the stars.

- Wait until the Southern Cross becomes vertical in the sky.

- Imagine a vertical line extending from the Southern Cross down to the horizon.

- This line will point you towards the south.

What is the distinction between navigating by the night luminaries at sea and on land?

When on land, it is not challenging to locate landmarks for determining the direction. All the methods described above can be utilized. However, when in the open sea, navigation becomes more difficult as there is no opportunity to stand firmly on one’s feet and accurately draw lines relative to the horizon. Therefore, when using the night luminaries for calculations while at sea, it is crucial to be as observant as possible and, if feasible, employ a chronometer and sextant.

If the sky is completely covered with clouds or fog, it becomes impossible to navigate using the stars. One must wait for a break in the clouds and the visibility of at least one star.

In such situations, the two-peg method can be utilized.

Alternative methods of nighttime orienteering

If, for any reason, determining one’s location using the stars is not an option, there are other methods that can be employed:

- During the summer months, one can determine the north or south direction by observing the night sky. The northern direction will appear brighter as the sun sets on that side and is “closer”.

- To find your bearings, you can rely on a regular clock and the moon. Simply remember that the full moon is in the south at midnight, in the east at seven in the evening, and in the west at seven in the morning. With a waxing moon, the crescent moon is located in the western part of the sky.

- If you want to determine your geographic latitude, you can create a homemade circlet that measures the angle between the horizon and Polaris.

NOVELEKA Wristwatch. Photo by OZON

Utilizing the stars for orienteering without extensive knowledge and calculations may not provide precise coordinates of one’s location. However, these skills can be extremely valuable in emergency situations where alternative methods of finding one’s way are unavailable. For instance, when stranded in the mountains or forests without any means of communication.

How can one navigate using the Sun in unfamiliar terrain? Discover various navigation techniques.

Methods and guidelines for orienting oneself using the Moon in unfamiliar terrain.

Is it feasible to navigate in unfamiliar terrain without a map and compass? What resources can aid in navigation?

"Polaris" is easily located near the constellation of Ursa Major, commonly known as the Great Bear. While it is difficult to explain the exact process, it is best shown through demonstration. However, I will attempt to provide some guidance…. within the Big Dipper, there are four stars that form the shape of a "bucket", and three stars that make up its tail. Two stars within the tail serve as a starting point… by drawing a straight line from the lower star to the upper star, this line will lead directly to "Polaris". Despite its faint appearance, it can be spotted in a clear night sky….

By sending a message, you are giving consent for the collection and processing of personal data.

Please refer to our Privacy Policy for more information.

At present, there are 13 constellations in the zodiac, which are named after either real or mythical animals (the word “zodiac” in Greek means “circle of animals”). Throughout the day, the stars trace circular paths in the sky, with the center being the pole of the world. The closer a star is to the pole, the smaller the circles it traces. It is possible for a star to never dip below the horizon. In our latitudes, constellations such as the Big Dipper, the Little Bear, Cassiopeia, and the Dragon are examples of non-setting stars.

One of the largest constellations in the northern hemisphere, known for its seven prominent stars that create the Big Dipper, serves as a convenient starting point for identifying other stars. Locating this constellation should pose no challenge, as it can be found in the northern sky during the fall, in the northeast during the winter, and directly overhead in the spring. Each star in the Big Dipper carries its own unique name: Dubhe, which means “bear” in Arabic; Merak, which represents the “loins”; Fekda, meaning “thigh”; Megretz, indicating the beginning of the tail; Aliot; Mitsar; and Alkaid, which means “master”. All of these stars shine with a magnitude of either second or third. Adjacent to Mitsar, one can spot Alcor, a faint star with a fourth sidereal magnitude. In Persian, Alcor translates to “insignificant” or “forgotten”.

Locate the star formation known as Cassiopeia. To accomplish this, imagine a mental connection between the second star from the end of the “handle” of the Big Dipper (Mizar) and the celestial pole known as Polaris. Extend this connection further in your mind’s eye, and at the end of this straight line, you will come across a constellation that bears a striking resemblance to the letter “M” when observed from the northernmost point of the planet in the month of December. During the month of June, however, this same constellation appears inverted and takes on the shape of the letter “W”. This celestial formation is none other than Cassiopeia. The majority of this constellation is situated along the Milky Way and boasts numerous dispersed clusters.

Located between the “containers” of the Big Dipper and Little Dipper is the Dragon constellation, which stretches slightly towards the constellations of Cepheus, Lyra, and Cygnus. The “head” of the dragon is formed by four stars arranged in a trapezoid shape. Not far from the “head” is a brilliant star known as Vega.

To locate the constellations Gemini, Orion, and Taurus, you must first find the Bucket of the Big Dipper. Then, draw a straight line starting from the faintest star in the “container” called Megrez, and continue eastward through the rightmost star, Merak. Along this straight line, you will encounter two bright stars – these are the main stars of the Gemini constellation. The star above is Castor, and the star below is Pollux.

Now let’s head further to the southeast. In that direction, there is a cluster of stars where three exceptionally bright stars catch the eye, positioned almost in a perfect line. These stars are part of the constellation Orion and are known as Orion’s Belt. Moving southeast from Orion, you’ll come across the stunning blue star Sirius, while to the northwest lies the red star Aldebaran.

Impressing a lady doesn’t just rely on your irresistible looks and expensive timepieces; knowledge is key too. If you’re not familiar with the latter, then you’ll have to take the word of Magmen’s editorial team. But why simply rely on our word… we’re all for engaging discussions and solid arguments! This new material is centered around “reading” the celestial atlas – specifically, identifying constellations. After going through this article, you’ll know exactly how to amaze your (potential) significant other with your knowledge!

To begin your exploration of constellations, it is recommended to start with the Big Dipper – its easily recognizable shape makes it a great starting point. It is important to note that in the spring, the Big Dipper can be seen directly above in the northern hemisphere. In the summer, it moves towards the northwest of the sky, in the fall it shifts to the north, and in the winter it can be found in the northeast. By drawing an imaginary line connecting the two outer stars of the Big Dipper, you will come across the bright star Polaris, which belongs to the Little Dipper. Just above Polaris, you will notice a constellation in the form of the letter W – this is Cassiopeia, which is hard to miss.

Take into account that the Little Bear is positioned between the “Big Dipper” and Cassiopeia, and it is approximately equidistant from them. Moreover, the tail of the Dragon is located between the two Bears. Interestingly, where the “tail” can be found, the “head” is not far off! In this scenario, the “head” consists of four diminutive stars.

Exploring celestial geometry: From Gemini to the “winter triangle”

A group of U-shaped stars can be easily spotted above Orion, and among them stands out the orange “circle” known as Aldebaran, which is a prominent star in the constellation of Taurus. Moving above Gemini and to the left of Taurus, we can find the constellation of Ascendant, which features a yellow “dot” called Capella, that is even more visible in the sky compared to Aldebaran. If we look below Gemini (specifically in winter), we will see the white star named Procyon, which crowns the constellation of the Little Dog. Not far from Procyon, we can observe the most colorful star known as Sirius, which holds the position of “No. 1” in the constellation of the Big Dog. These three stars, Procyon, Sirius, and Betelgeuse, together form what is commonly referred to as the “winter triangle”.

The beauty of the summer and fall sky

Summer and fall are the ideal seasons for stargazing. With vacations, outdoor picnics, and leisurely evening walks, there is plenty of free time to indulge in this magical activity. The abundance of blooming greenery and the soothing sound of the sea create a romantic atmosphere, making it the perfect time to share something intriguing with a special someone. Interestingly, you don’t need to venture far to enjoy this experience. Simply look up, turn your face towards the south (with the east to your left and the west to your right), and observe the sky map unfolding before you, as if it were held in the palm of your hand.

As the evening progresses, three stars that can be seen with the naked eye appear in the sky (and directly above, i.e. in the zenith) as the Moon follows its path. Positioned on the right is Vega, the central star of the Lyra constellation, which is one of the most prominent stars in the northern hemisphere (ranking after Sirius and Arcturus). On the left side is Deneb. Deneb serves as the focal point of the Swan constellation, which can be easily identified by its cross-like formation: one group of stars represents the bird’s “wings,” while the other forms its body and neck. Lastly, completing the trio of stars is Altair, the pinnacle of the Eagle constellation. Collectively, Vega, Altair, and Deneb form the “summer-autumn triangle” – a distinctive pattern in contrast to a similar arrangement seen during the winter season.

To the left of Lyra, you may notice Hercules – although, admittedly, even someone who took a special astronomy class in school may struggle to do so. However, if you pay close attention, you will observe an inverted and mirrored letter K next to Lyra – this represents the “body” of Hercules, with the “limbs” extending outwards. Locating Scorpius in the night sky is certainly not challenging – it can be found in the southern region, nearly on the horizon. The distinguishing feature in this case is the red “circle” Antares. Scorpius is positioned directly on the Milky Way, the galaxy that encompasses our own solar system.

In summary, our lecture has highlighted the dynamic nature of astronomy, and the starry sky serves as a fascinating guide. Acquiring a basic understanding of interpreting it will greatly aid in discovering new constellations. The practical advantages are substantial: not only will you impress others with your intelligence, but you can also pleasantly surprise someone by effortlessly locating the zodiac sign under which they were born. The effort put into this endeavor is truly rewarding, trust me!

Stars in the Northern Hemisphere

In order to determine the position of a ship using astronomical techniques, it is sufficient to be familiar with the names and locations of 10-15 stars that are spread across different areas of the sky. However, the appearance of the night sky constantly changes throughout the day. Therefore, it is necessary to be familiar with approximately 40-50 stars for practical purposes and to have the ability to navigate using the stars.

The study of the northern starry sky should be based on the constellation of the Big Dipper, which has the shape of a ladle with a handle.

1. On the extension of the line that connects the stars b and a of the Big Dipper, after approximately five distances between these stars, we will come across a relatively dim star known as Polaris, or alpha of the Little Dipper.

2. If we extend the distance from a to b of the Big Dipper six times, we will discover the constellation Leo, which is characterized by its bright stars forming the shape of a sickle. In this constellation, a represents Regulus, while b represents Denebola.

3. If we extend the arc that forms the handle of the Big Dipper towards the star h, we will find the prominent star Alpha Volopasa, also known as Arcturus. This star is located next to the constellation of Volopassus, which has a distinct horseshoe shape. In the center of this horseshoe shape, we find the brightest star, alpha – Alphacca, of the Northern Crown constellation.

4. By continuing along the arc in direction 3 from h of the Big Dipper, beyond Arcturus, for a similar distance, we will encounter the bright star Spica, or alpha Virgo.

5. If we extend the direction 1 from b to a of the Big Dipper beyond Polaris, we will come across the constellation Pegasus, which has the form of a large square. At the top of this square, we can find the bright stars a – Markab and b – Seat.

6. Starting from the bright star e of the Big Dipper (the third star from the end of the handle), and passing through Polaris, we reach the constellation Cassiopeia. This constellation has a distinct shape resembling a stretched letter W. Its a represents Shedar, while its b represents Caff.

7. If we continue in the direction 6, beyond Cassiopeia, we will reach the constellation Andromeda. The star a of Andromeda, Alpheras, is located in the corner of the square formed by the constellation Pegasus but is not part of it.

8. By traveling from Polaris through e of the Big Dipper (retracing direction 6), we reach the region of the Virgo constellation. This constellation can also be found by following direction 4.

9. On the diagonal line connecting d and b of the Big Dipper, approximately four or five distances between these stars, we find the constellation Gemini. In this constellation, the bright stars a and b represent Castor and Pollux, respectively.

10. If we continue in the direction 9, behind Pollux, for another four distances between d and b of the Big Dipper, we discover the constellation of the Big Dog. The brightest star in the entire sky, a, is known as Sirius. About halfway between Pollux and Sirius, we find the constellation of the Lesser Dog, with the brightest star a being Procyon.

11. At a distance of approximately five or six distances between d and b of the Big Dipper, we encounter the Ascendant constellation. The very bright star Capella represents a in this constellation. It can also be identified by the noticeable elongated triangle of faint stars nearby.

12. By extending the line from Polaris to Capella, we reach the Orion constellation, which is easily visible during the fall and winter seasons. The bright stars in this constellation are: a – Betelgeuse, b – Rigel, and g – Bellatrix. The constellation itself has the shape of a large trapezoid, and the three small stars in the middle are commonly referred to as Orion’s Belt or the Three Magi.

13. Along the line g – a of Orion, at a distance of four intervals between them, we can also locate the previously mentioned star, Procyon.

14. Extending Orion’s Belt further will lead us to Sirius and the constellation of the Big Dog.

15. If we continue along the belt of Orion in the opposite direction of Sirius, at the same distance, we will find the reddish star a Taurus, known as Aldebaran.

16. In the middle of the distance between Aldebaran and Cassiopeia, we encounter the Perseus constellation, with its a representing Mirfak. The constellations of Taurus and Perseus can also be identified by the well-known star cluster Pleiades, which is located between them and appears as a dense scattering of small stars (popularly known as the Seven Sisters).

17. By traveling from g through d of the Big Dipper, at a distance of fifteen to sixteen intervals between them, we arrive at the region of the Eagle constellation in the Milky Way. The alpha star of this constellation is Altair. Not far from this line, closer to Altair, we find the bright star Vega, which represents the Lyra constellation. On the other side of the Milky Way, we encounter the Swan constellation, which takes the shape of a flying bird. The star Deneb represents the Swan. Altair, Vega, and Deneb form what is known as the Triangle of Large Stars, which can be easily identified by its location along the Milky Way.

18. By extending from h of the Big Dipper through the Volopassus constellation, past the Northern Crown, we discover the Scorpius constellation. The star Antares represents a in this constellation and is notably reddish in color.

19. Along the d – g line of the Big Dipper, passing through Regulus, we find the Hydra constellation, which stretches out like a long ribbon. The only bright star in this constellation is Alfard. Other constellations that can be found include Hercules, located between the Northern Crown and Lyra constellations; Aries, with the star Hamal, near Andromeda; Snake, near the Northern Crown, towards Antares; Serpent, between the Scorpius and Eagle constellations; and Dragon, which takes the form of a long ribbon starting between the Big and Little Bears and ending near Vega.