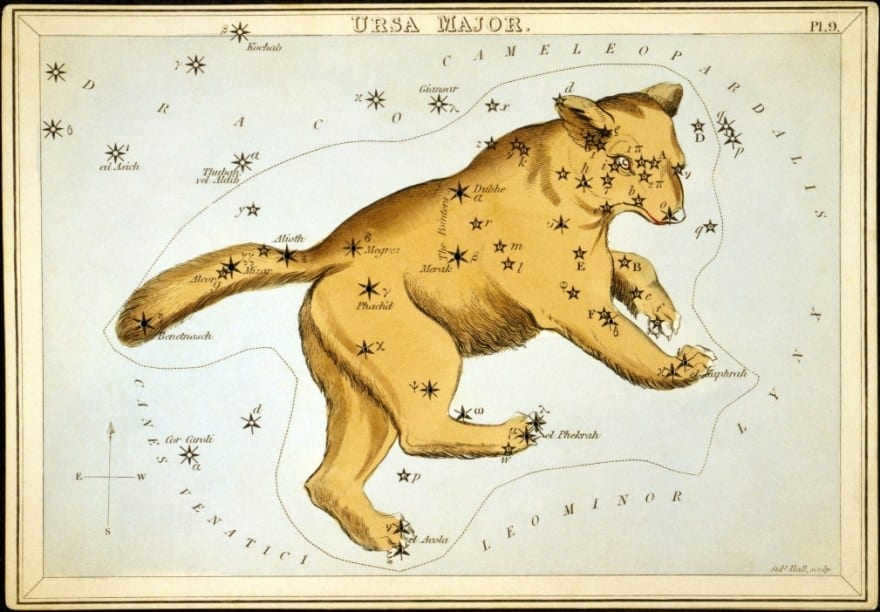

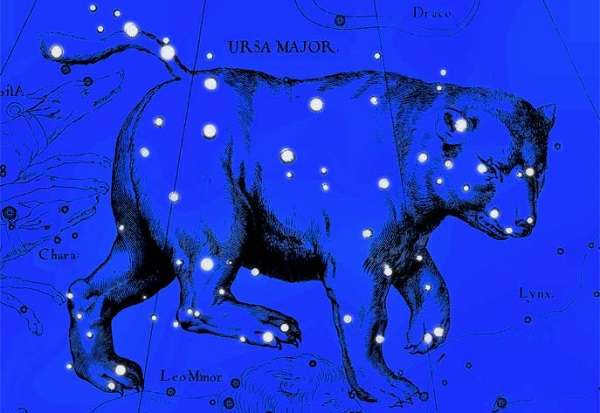

The Big Dipper is a well-known constellation in the night sky. With its bright stars, it is easily recognizable even without the use of a telescope. In ancient times, it was used as a guide for travelers, and today astronomers continue to study this cluster of stars. The Big Dipper is a frequent subject of observation, leading to exciting discoveries and a greater understanding of the universe.

Description and Characteristics of the Big Dipper

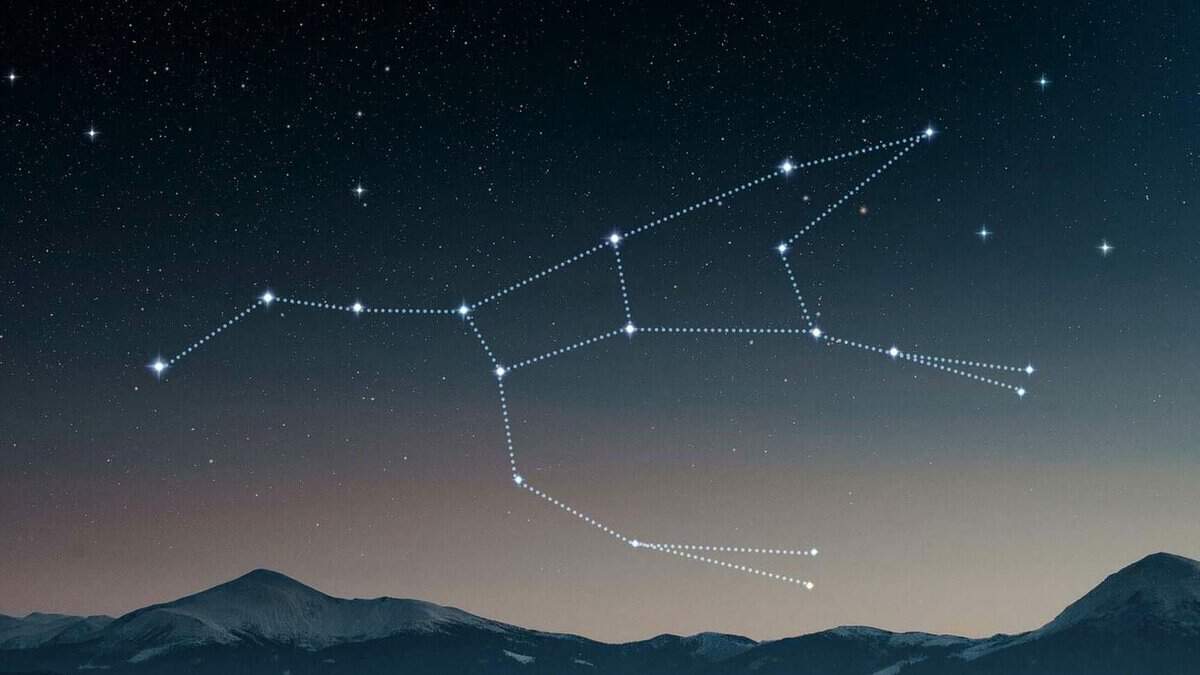

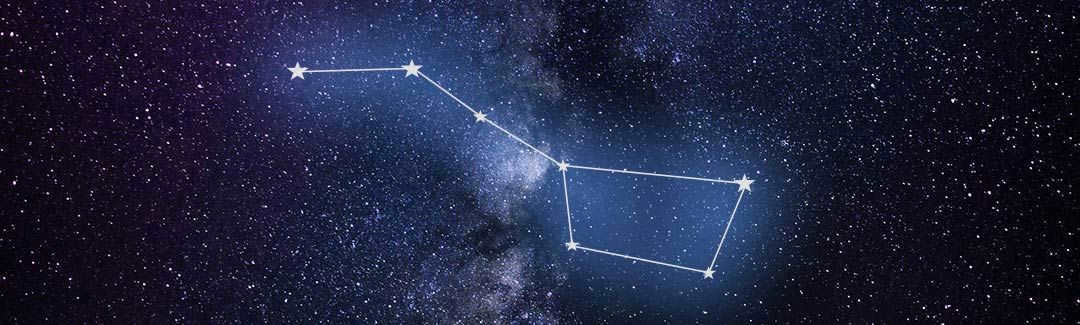

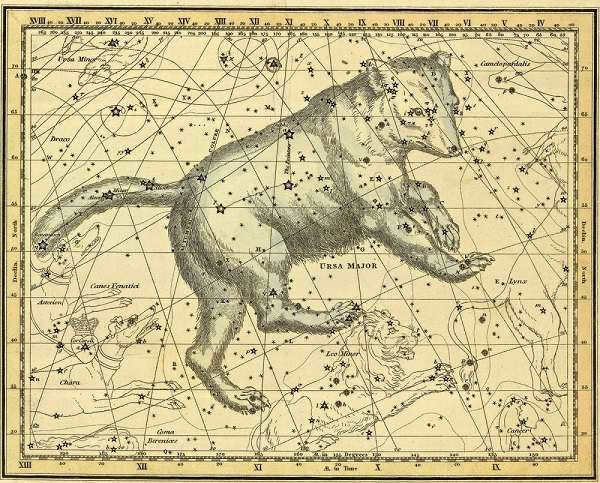

The Big Dipper, also known as the Plough, is a prominent asterism in the constellation Ursa Major. It is one of the most recognizable star patterns in the northern hemisphere. The Big Dipper is made up of seven bright stars that appear to form a shape resembling a ladle or a saucepan.

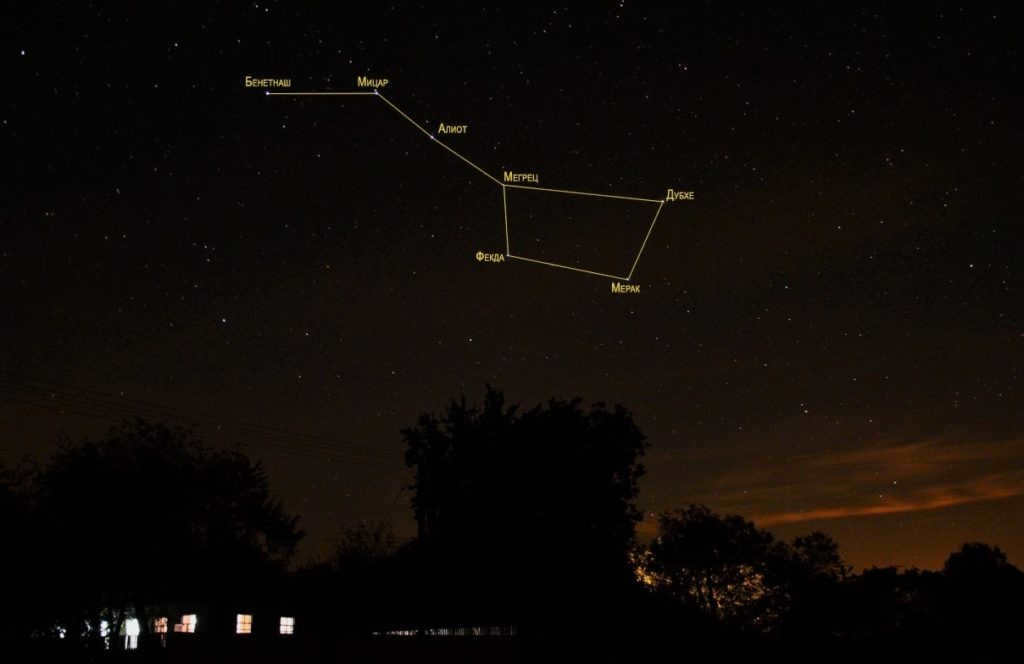

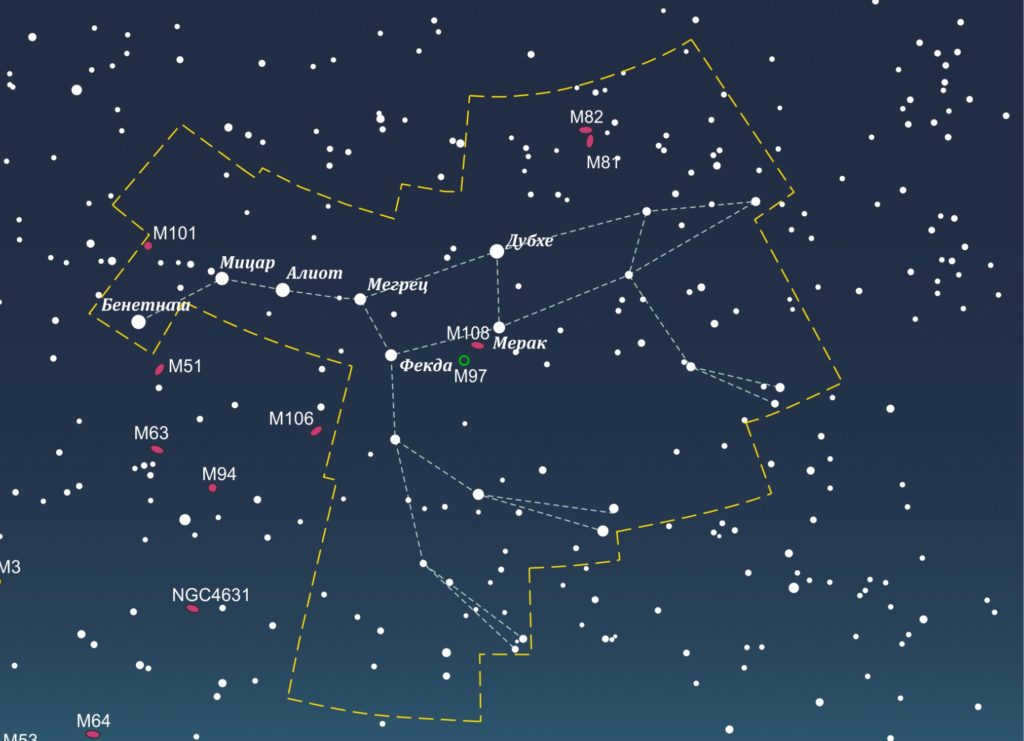

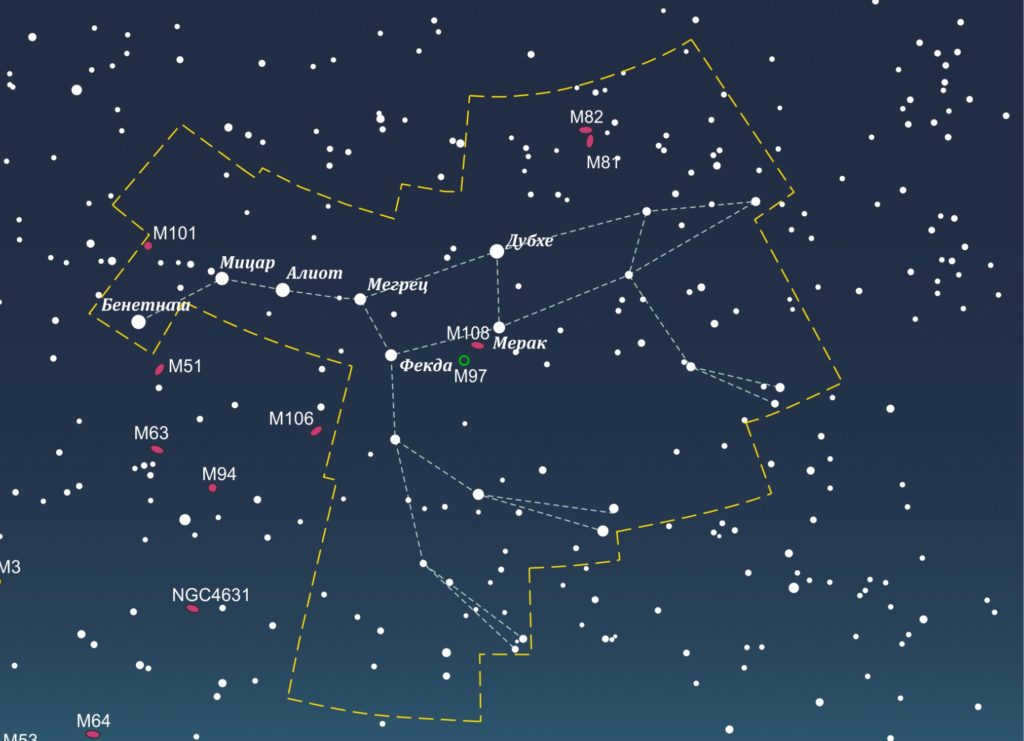

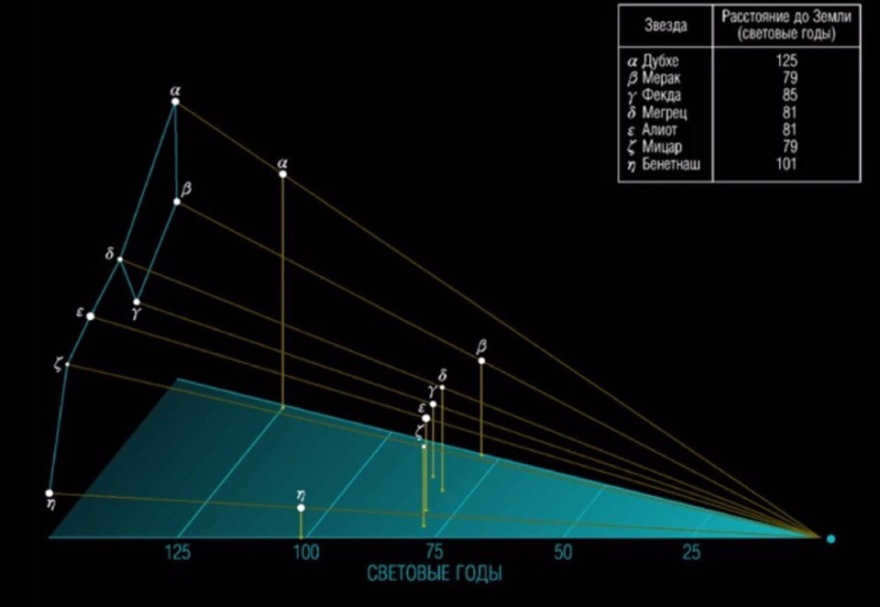

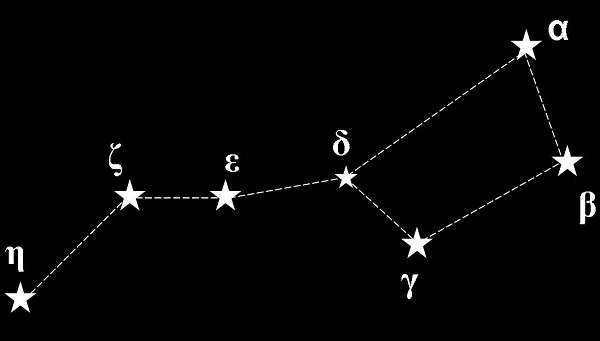

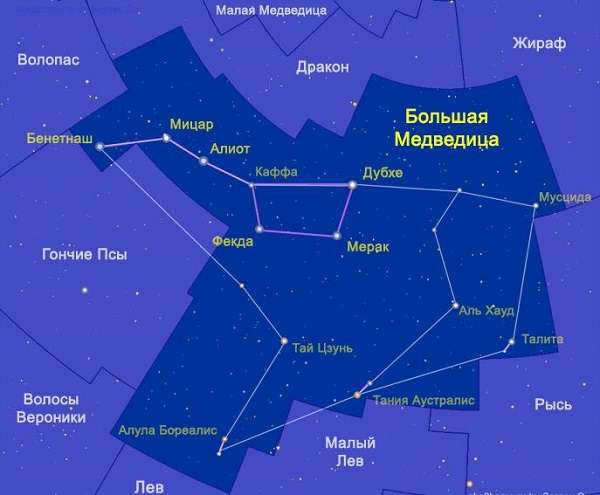

The stars that make up the Big Dipper are Dubhe, Merak, Phecda, Megrez, Alioth, Mizar, and Alkaid. These stars are all part of the Ursa Major Moving Group, which is a collection of stars that share a common origin and are moving together through space.

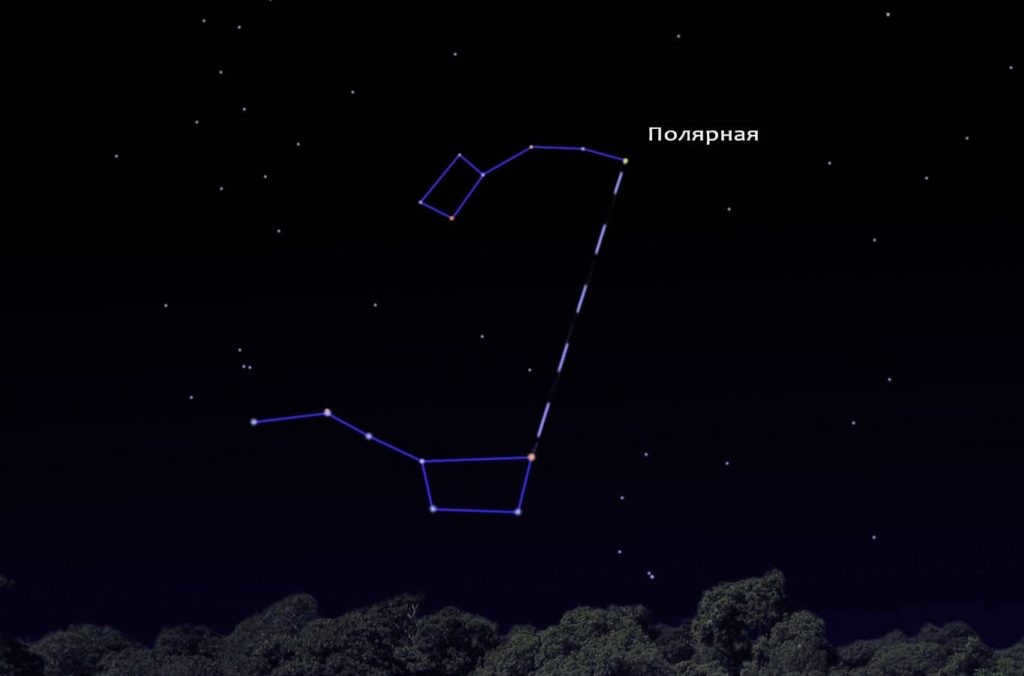

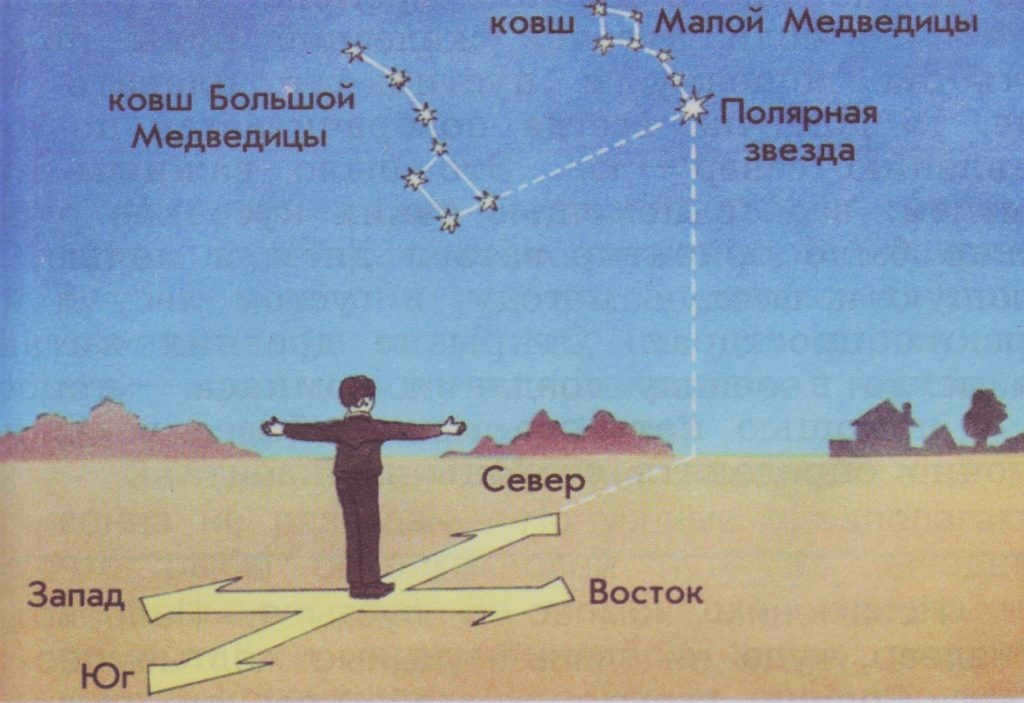

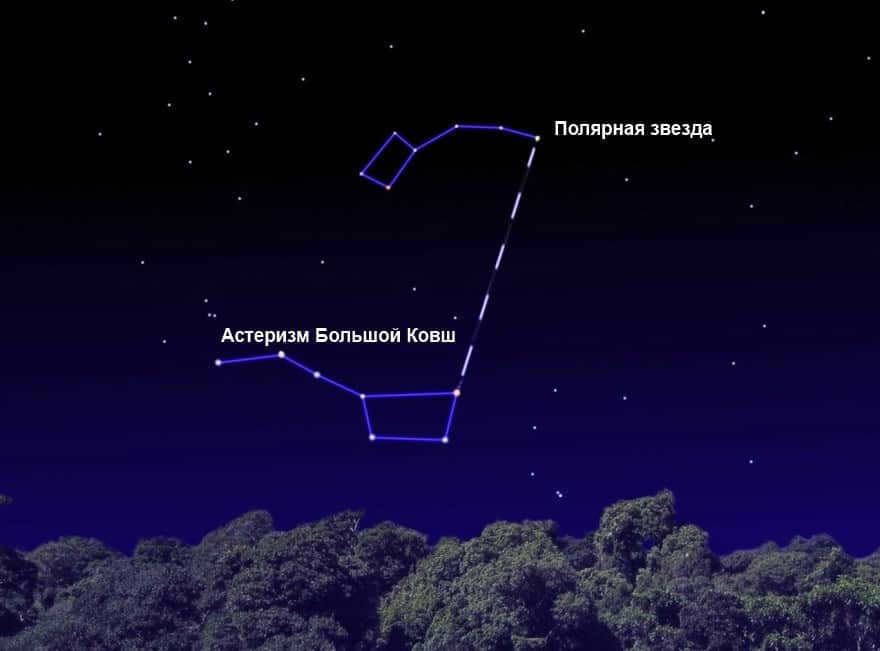

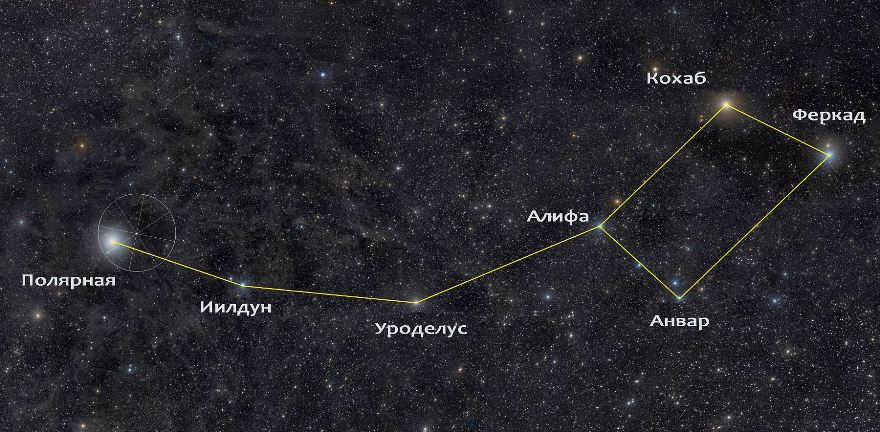

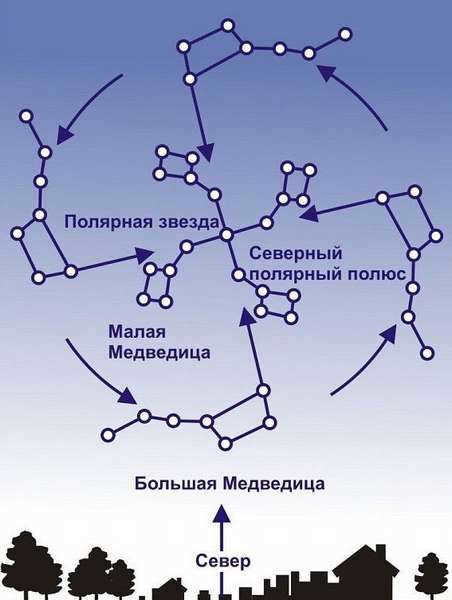

The Big Dipper is easily identifiable by its distinctive shape and prominent position in the night sky. It can be used as a navigational tool to locate other stars and constellations. For example, by following the line formed by the two stars at the end of the ladle, Dubhe and Merak, one can find the North Star, Polaris.

In addition to its navigational uses, the Big Dipper has cultural and mythological significance in many different societies. It has been used as a symbol of strength and guidance, and its appearance in the night sky has been associated with various legends and stories.

Overall, the Big Dipper is a fascinating and easily recognizable feature of the night sky. Its distinctive shape, bright stars, and navigational significance make it a popular subject of observation and study for astronomers and stargazers alike.

The Big Dipper is known as the third largest constellation in the night sky. It covers more than 3% of the celestial sphere and spans an area of approximately 1279.66 square degrees. This constellation revolves around Polaris, which means it is visible above the horizon at all times of the year.

Comprised of seven prominent stars, the Big Dipper resembles a bucket with a handle. In Latin, this constellation is referred to as Ursa Major and is abbreviated as UMa.

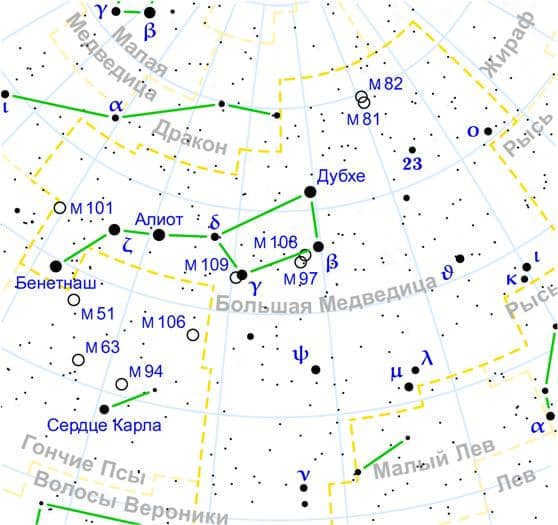

Due to its considerable size, the Big Dipper shares borders with several other constellations. Some of its neighboring constellations include Draco, Camelopardalis, Coma Berenices, Canes Venatici, and Leo.

Fascinating information: There is a fascinating belief among Native Americans that the Big Dipper’s descent to the horizon in the fall signifies the animal’s preparation for winter hibernation.

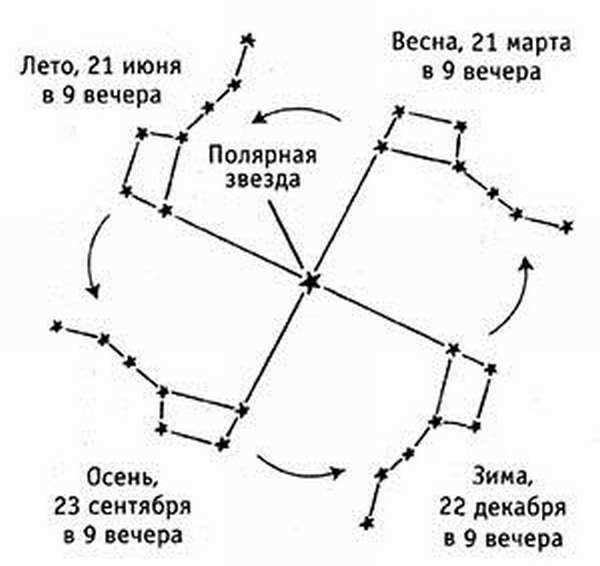

In Russia, the constellation remains visible throughout the year, but its stars shine particularly bright in April compared to other months. By observing the movements of the Big Dipper, one can determine the month and approximate date. In ancient China, people even used the position of the handle of the Bucket to tell time.

What is the method of locating the constellation of Ursa Major in the celestial sphere?

Locating constellations in the night sky can be quite challenging without specialized equipment. However, identifying the Big Dipper is relatively easy due to its distinctive shape. Once a person finds this group of stars, they can easily determine their location.

During late summer and early fall, the Big Dipper can be found in the northern part of the celestial sphere. For optimal viewing, it is recommended to wait until nighttime and venture outside of urban areas where the lights from houses and streetlamps won’t interfere with stargazing.

Did you know? The position of the Sun at noon can be used to determine the north. At this time, the star can be found on the opposite side, in the south.

During autumn, the asterism can be found high in the sky, positioned horizontally. The stars that form this asterism are bright enough for the human eye to easily spot, and our brain connects them in straight lines to form a recognizable object.

As the Earth orbits the Sun and rotates on its axis, the arrangement of constellations in the night sky gradually changes when observed from a specific point. As a result, between January and February, the Big Dipper slowly rotates in a circular motion: The dipper’s bowl tilts downwards, away from its horizontal position. Additionally, the overall position of the cluster gradually shifts towards the northeast.

In spring, locating the Big Dipper in the starry sky becomes more challenging. During this time, the asterism is positioned with its “lid up,” making it easily overlooked by an unaware observer.

The Big Dipper is most easily seen in the northern regions of Russia, where the phenomenon of white nights often obscures the visibility of stars. However, in the middle and southern regions, it is important to note that the orientation of the constellation may appear inverted, with the handle of the Bucket pointing upward.

The Big Dipper is considered one of the oldest constellations as it is mentioned in the records of nearly all ancient civilizations. In India, it was known as “Sapta Rishi,” which translates to “seven sages,” due to its seven main stars that form the shape of a bucket. The Chinese also observed the Big Dipper and used its position in the sky to determine time.

In Greek mythology, there is a beautiful legend that surrounds the constellation known as the Big Dipper. It is said that Zeus, the king of the gods, had a tendency to be infatuated with beautiful young women. One such woman was Callisto, the daughter of the king of Arcadia. However, Zeus’ wife, Hera, discovered their affair and sought revenge. In order to protect Callisto from Hera’s wrath, Zeus transformed her into a bear and placed her in the sky, where she would be safe from harm.

The Indians also recognized the constellation as a bear, but their interpretation differs slightly. They see the bear as consisting of four stars arranged in the shape of a trapezoid. The handle of the Big Dipper is seen as three hunters who are chasing the bear. The first hunter, Aliot, is depicted holding a bow. The second hunter, Mitzar, is shown carrying a cauldron. Finally, the last hunter, Benetnash, is seen with a pile of brushwood for kindling a fire.

Stars in the Ursa Major Constellation

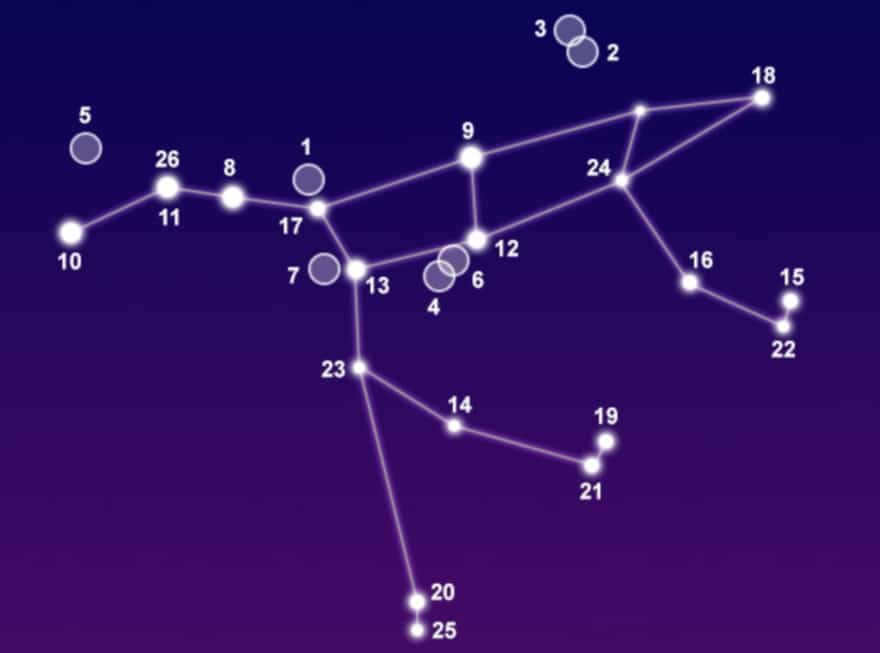

The Big Dipper is composed of a remarkable number of stars. However, within its constellation, known as the Dipper, there are only seven stars that form a unique shape. Modern technology allows astronomers to continuously observe these stars and gather the necessary data. The Dipper constellation is made up of:

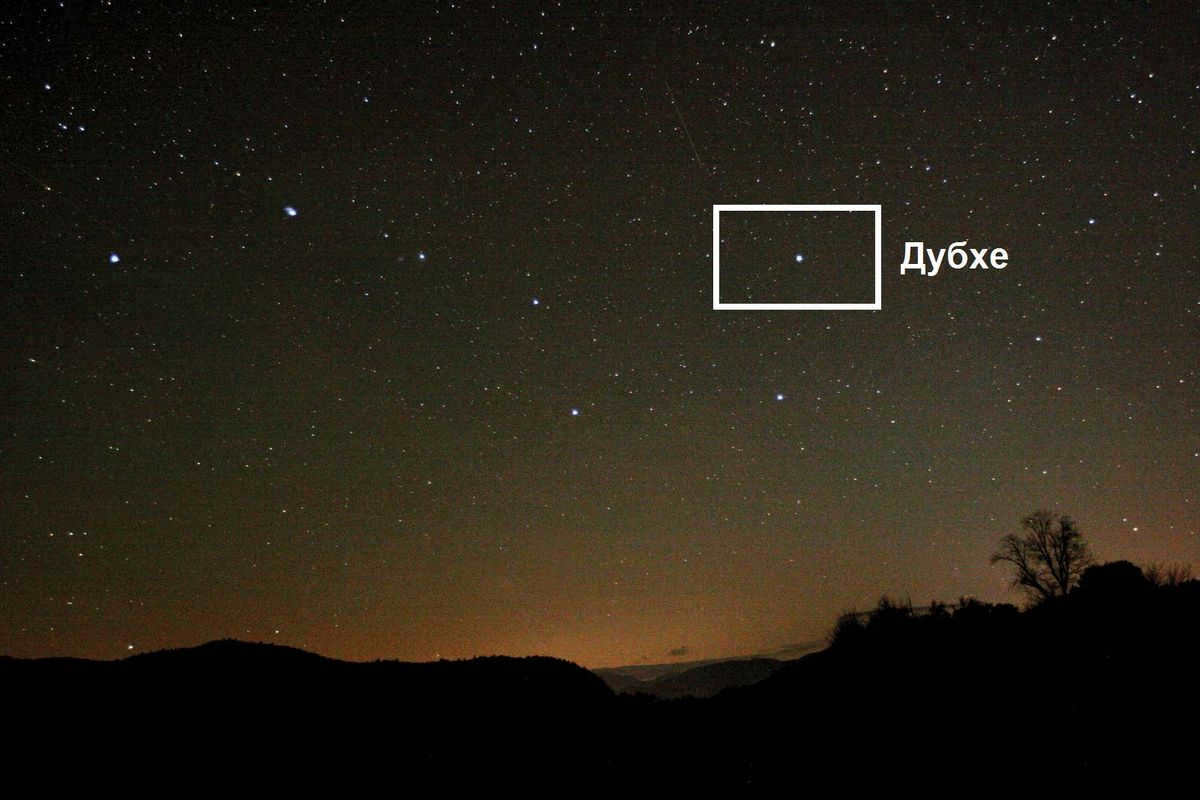

- Dubhe – serves as the alpha and is considered the second brightest star in the constellation. Detailed studies have revealed that Dubhe consists of two stars: the main sequence star and the orange giant.

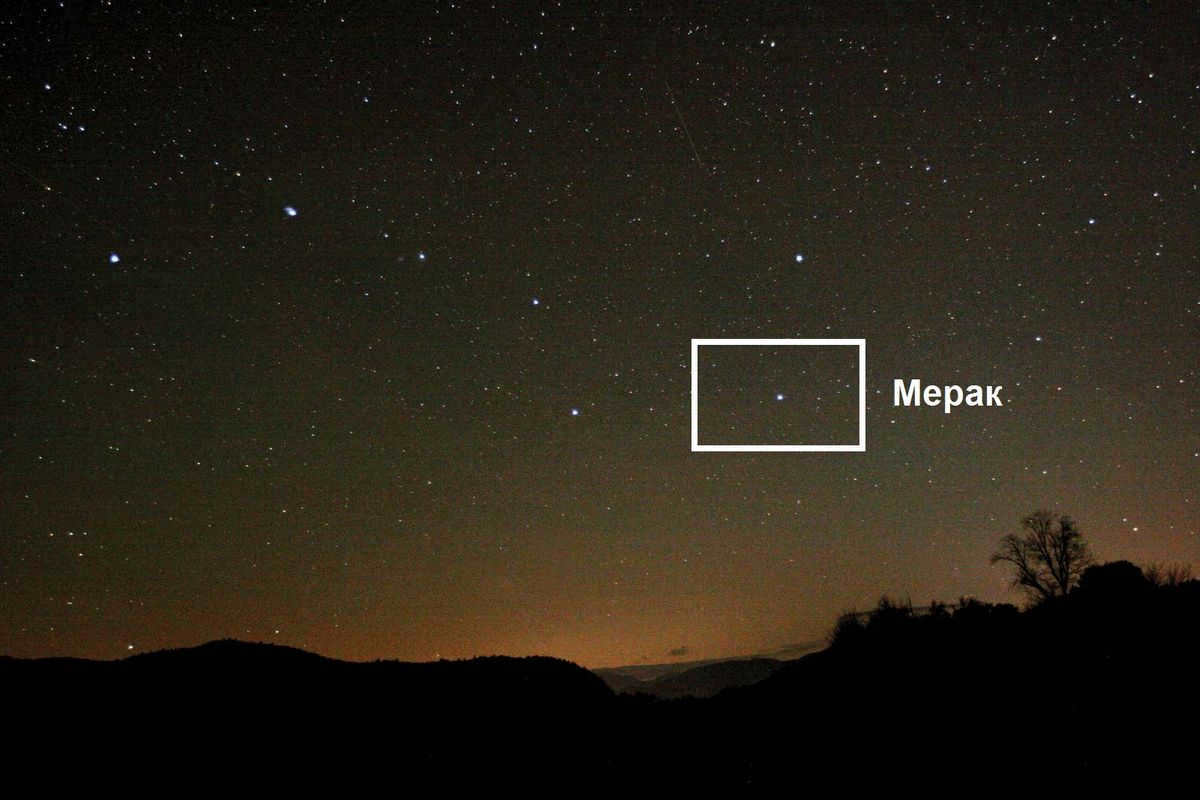

- Merak is the beta star of the cluster. Although not the most prominent in the night sky, it shines 69 times brighter than the Sun.

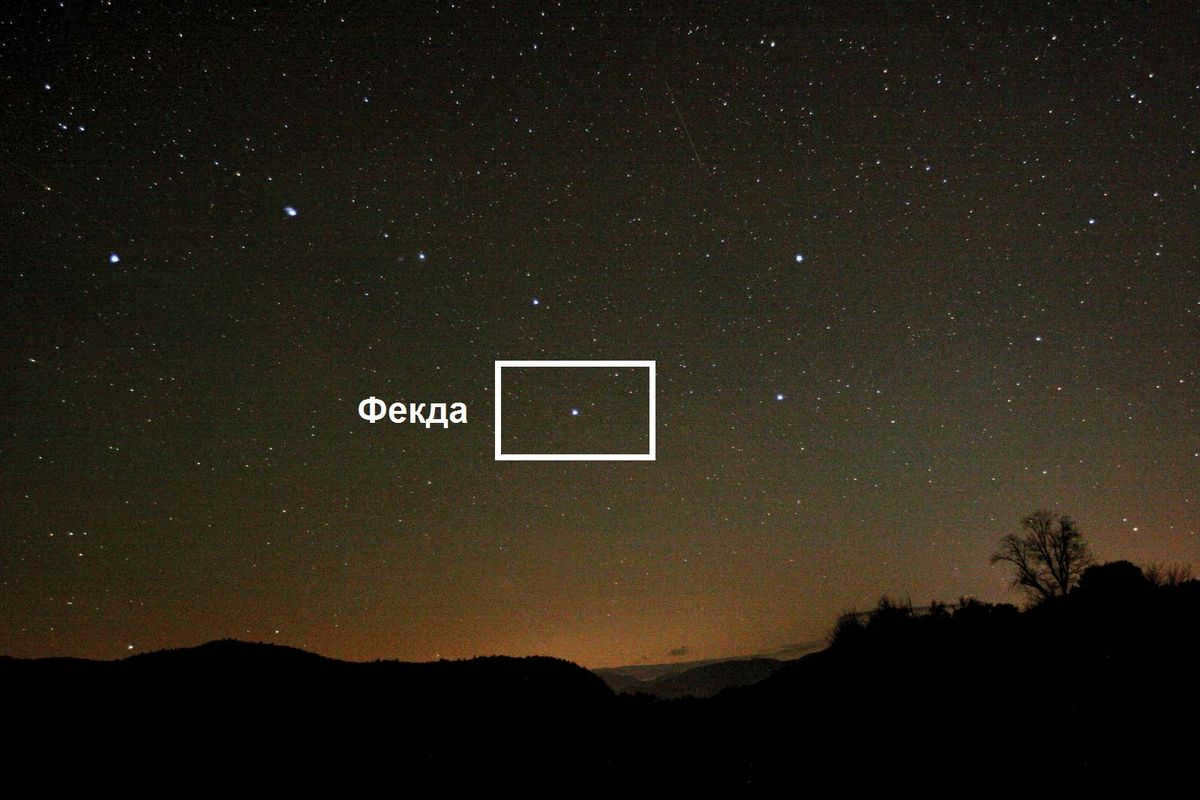

- Fekda – a celestial body positioned beneath the knob, at the bottom of the Bucket.

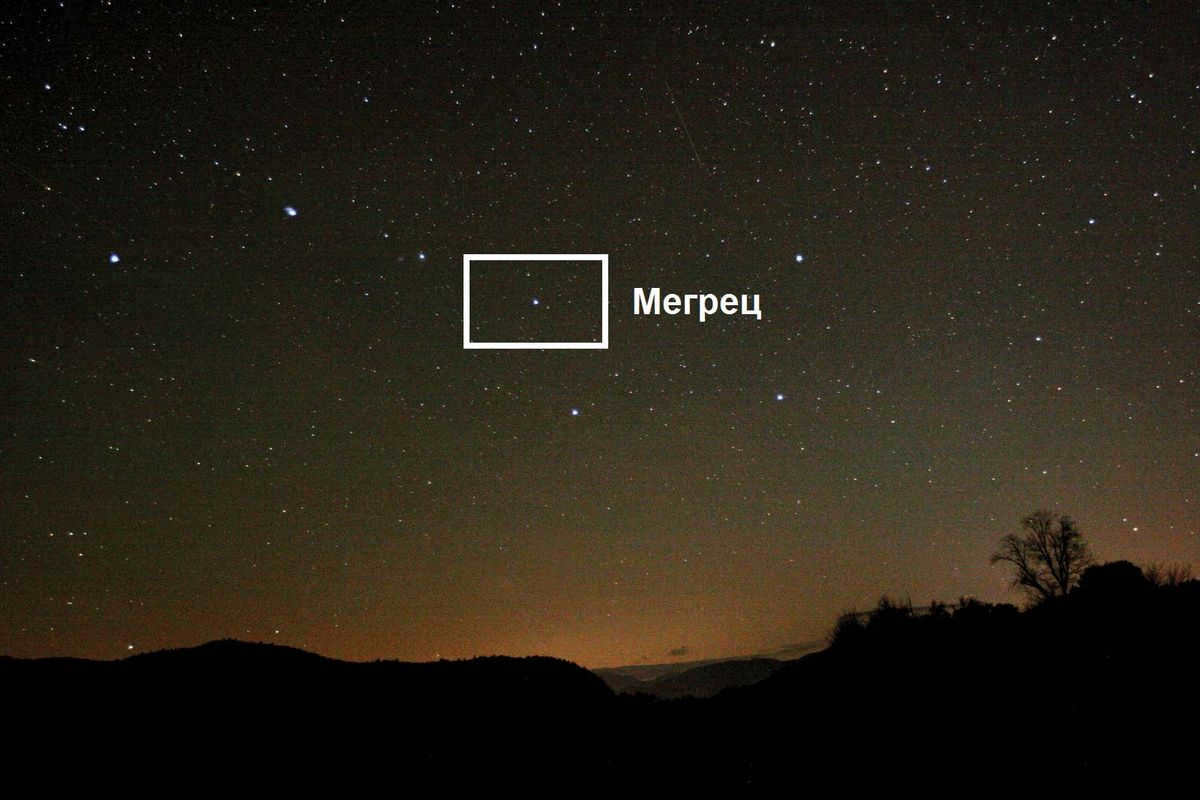

- Megretz is the least bright star in the constellation of the Big Dipper.

- Aliot – the most brilliant star in the cluster, highly visible in the night sky.

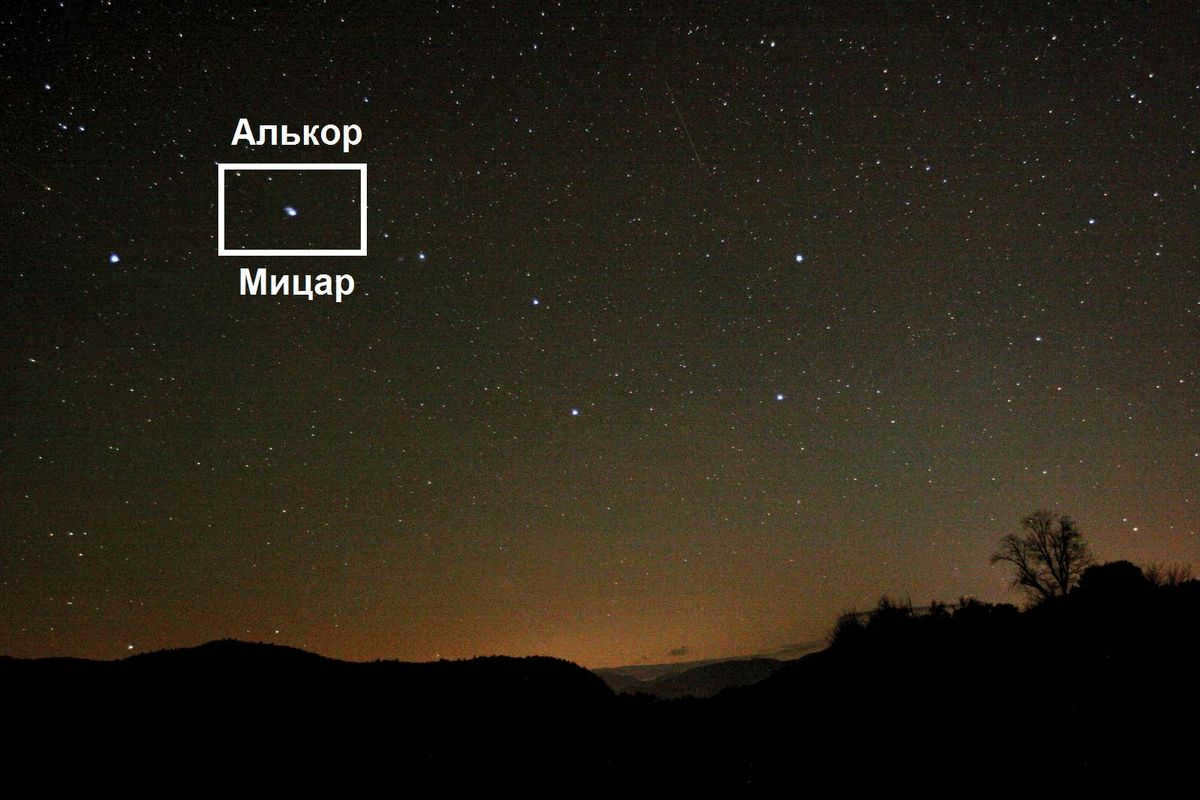

- Mizar – not easily visible due to the presence of Alcor, a neighboring star that is nearly twice as luminous.

- Alcaide is the most remote luminary from the main group, situated at the end of the handle of the Bucket.

In addition to the seven stars in this asterism, the constellation contains approximately 125 other stars. However, only a few dozen of them can be detected by the naked eye. The most prominent are the three stars located to the right of the Dubhe-Merak pair, which form a triangle. In the lower right corner of the Bucket, there is a similar formation composed of the stars lambda, mu, and psi.

An intriguing fact: in certain societies, these two triangles symbolize the hind and front limbs of a bear.

Moreover, there are several prominent stars situated to the right of the Big Dipper, and in Russia, only two luminaries are concealed below the horizon. Since the constellation remains visible in the Russian Federation’s sky at all times, local astronomers and enthusiasts of stargazing can effortlessly locate the following celestial objects:

- Polaris;

- Cassiopeia;

- the Leo constellation is nearby;

- the stars Capella and Arcturus;

- the Gemini constellation;

- the Virgo constellation.

If you are aware of the direction in which these objects are positioned with respect to the Big Dipper, finding them becomes a breeze.

The assortment of items in the Great Bear

Only the Owl Nebula, also known as M97, can be observed in an amateur telescope from the objects of the Big Dipper. The rest of the objects require professional equipment for visibility. Adjacent to the Owl Nebula is the star Merak.

The region of the sky where the Big Dipper is located is home to approximately one and a half thousand galaxies that are of interest to astronomers. Being situated in the Milky Way, most of these galaxies can be seen through a professional telescope.

Situated at a distance of 12 million light-years away from our planet Earth, we can find the galaxies known as Cigar, Bode, and Vertushka, which are designated as M82, M81, and M101 respectively. Among these, the first one is widely regarded as one of the most stunning objects present in the vast expanse of space. This is primarily due to the fact that its arms emit a beautiful violet-blue glow, while the central part appears as a distinct blue sphere.

The spiral-shaped Vertuska galaxy showcases elegant, curved tails that stretch outwards, with numerous bright celestial objects scattered around it. Many astronomers have even likened these objects to a mesmerizing fireworks display, as they bear a striking resemblance to exploding fireworks.

The galaxy M108 can be found near the star Merak. Its center cannot be observed due to the presence of dust clouds, which also absorb its brightness. When viewed from Earth, the brightness of M108 is approximately 12m.

Located not far from the Feqda luminary, the galaxy known as M109 is visible. It is considered to be one of the most challenging objects to observe, as its glow is often overshadowed by nearby stars.

Astronomers regularly discover new galaxies with unique characteristics while observing the region where the White Bear is located. Its favorable position in the sky allows for the observation of even the most distant objects.

The Big Dipper: the pail during autumn

Due to the continuous movement of celestial objects, the Great Bear can be found in different parts of the night sky depending on the time of year. During the autumn season, many stars remain hidden from view. However, the constellation’s famous pattern is an exception to this. Although slightly dimmer between September and November, the seven main stars of the Big Dipper can still be observed with the naked eye.

During the fall, the Great Bear can be found in the northern part of the sky, below the North Star. The “dipper” part of the constellation faces west, with the handle pointing towards it. Towards the east, the Pleiades constellation is visible, accompanied by the shining presence of Aldebaran. To the northeast, the prominent stars that form the Gemini constellation can be seen.

However, not all constellations are visible during the autumn season. In Russia, the Virgo and Leo clusters extend beyond the horizon, and the Eagle cluster is barely visible from the western region, hiding behind the Big Dipper.

The fall sky is known for its particularly bright constellations:

These clusters can be observed at night without the need for special equipment. Astronomers, though, utilize professional telescopes with sufficient power to bring stars and galaxies of interest closer. For instance, the Hubble telescope is capable of observing over a thousand galaxies located within the stellar sector of the Big Dipper. Thanks to this technology, scientists are able to work continuously without having to take seasonal breaks.

Common Misconceptions Surrounding the Origins of the Big Dipper

There are various legends surrounding the origin of this constellation. One of the most fascinating and widely known is the Greek myth. As mentioned earlier, it revolves around a girl named Callisto, who was the daughter of the king of Arcadia and caught the attention of Zeus.

However, there is an alternative version of the myth. In her youth, Artemis frequently ventured into the forest for hunting, seeking different types of game. Accompanying her were young girls of exceptional beauty. Among them, Callisto stood out with her remarkable appearance.

Zeus was drawn to Callisto because of her beauty. To gain her favor, the god disguised himself as Artemis. Eventually, Callisto gave birth to a son named Arcades. When Zeus’ wife Hera discovered his actions, she angrily transformed Callisto into a bear, giving her an unappealing appearance.

Did you know? The stars Benetnash and Duhbe in the constellation Ursa Major, also known as the Big Dipper, move in a different direction than the other stars. As a result, the shape of the Big Dipper gradually changes over the course of the year.

What is the optimal moment to observe the Big Dipper

In order to observe the Big Dipper in Russia, one must venture outside the city where the light pollution doesn’t obstruct the view of celestial objects. The optimal time to witness this constellation is during the months of March and April.

Did you know: During the first weeks of April, residents of Moscow can witness the Big Dipper directly overhead.

During these specific months, the Big Dipper ascends to its highest point in the sky, and every night around 11:00 PM, the stars shine their brightest. By looking up, one can easily locate the constellation. And with the aid of even a basic pair of binoculars, they will be able to observe not only the seven main stars, but also nearby objects.

Observing the Big Dipper in autumn is not ideal as it loses its brightness and requires a telescope to see the neighboring stars associated with the constellation.

Using the Big Dipper as a guide

Thanks to its significant brightness, the Big Dipper has been a reliable point of reference for people throughout history. Depending on the time of year, experienced navigators could use the Big Dipper to determine the cardinal directions and navigate with precision.

Most importantly, the Big Dipper can help locate Polaris in the night sky. By drawing a straight line from the star to the Earth, one can accurately determine the direction of north.

Fascinating fact: In ancient Russia, the constellation was known as the Horse due to its distinct shape. The polar star was believed to be a peg to which the mythical horse was tethered.

By recognizing the position of the north, one can immediately ascertain the whereabouts of the other directions: south – behind, west – to the left, east – to the right. Aiding in spatial navigation are the stars Arcturus and Spica, which can be found in the southern region. During the Middle Ages, seafarers relied on these stars to accurately establish the correct course while sailing through the vastness of the night sky.

The advantage of using the Big Dipper as a point of reference is that it spans a significant portion of space. Even in cloudy weather, there is a high likelihood that at least a portion of the constellation will be visible in the celestial sphere. This alone is sufficient for determining the position of the north.

Engrossing footage of the Majestic Bear

If you stumble upon any inaccuracies, kindly highlight the specific text and press Ctrl+Enter.

The Ursa Major constellation, also known as the Big Dipper, is undeniably one of the most renowned and easily identifiable star patterns that grace the celestial sphere at night. Its visibility spans across the entire Northern Hemisphere, making it a prominent fixture in the sky. This constellation served as an invaluable reference point for ancient travelers and continues to captivate the attention of modern astronomers, who are unraveling the enigmatic secrets of the universe through its study.

Description

This constellation is quite large and covers about 3% of the night sky. It spans an area of approximately 1279 square degrees. The Big Dipper revolves around the star α of the Little Bear, also known as Polaris, and can be easily seen during the nighttime. It is always visible and never disappears below the horizon in the middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere.

Within the Big Dipper constellation, there are 7 stars that standout due to their brightness compared to other celestial objects. They are easily visible during the darkest hours of the night and form the shape of a “bucket”. The Latin names for this constellation are Ursa Major and UMa. Near the Big Dipper, you can also observe the following constellations:

- Hound Dogs

- Giraffe

- Dragon

- Leo

- Veronica’s Hair

- Little Lion

The most brilliant stars of the Big Dipper

This constellation consists of 125 celestial bodies. The most luminous ones are the seven stars that create a recognizable pattern. They have Arabic names and are grouped together as the Big Dipper. Modern technology allows scientists to study this portion of the sky extensively. The bright stars of the Big Dipper serve as helpful guides for navigation.

Dubhe

Dubhe is a binary star system and is known as the alpha star of the Big Dipper constellation. It is named after its position as the “back of the bear”. This star system is located at a distance of over 120 light years from Earth. The primary component, known as A, is classified as an orange giant. Due to its location off the main sequence, the age of Dubhe is currently unknown. The secondary component, known as B, is a small white-yellow dwarf that is classified as being on the main sequence.

Star A has a mass that is 5 times greater than the mass of the Sun, while star B has a mass that is only one-sixth of the solar mass. The radius of star A is 30 times larger than the solar radius, while the radius of star B is one-third of the solar radius. The orange giant is slightly cooler than the Sun, with a surface temperature of 4700 °K. On the other hand, the dwarf star is red-hot, with a surface temperature of 6500 °K.

Dubhe has a stellar magnitude of 1.09, making it the second most luminous star in the Big Dipper. This star is easily located in the upper portion of the dipper.

Merak

This subgiant has a stellar magnitude of 2.34. The name of this star means “loins” or “groin”. It has a mass 2.6 times that of the Sun and continues to accrete matter from the surrounding molecular cloud. Merak has a radius 3 times that of the Sun and a temperature exceeding 9800 °K. It is located 96 light-years away from Earth. While not the brightest star, Merak shines approximately 70 times brighter than the Sun.

The star is expected to consume its hydrogen fuel in its core for approximately 500 million more years. After that, the fusion of helium will commence in its core. This phase is estimated to last around 200 million years. As the star cools down, it will expand and transform into a red giant.

Phecda.

Phecda has a brightness of 2.41. The Arabic translation of its name means “thigh”. Phecda ranks as the sixth brightest object in its group of stars. It can be found in the lower section of the constellation. This star is situated approximately 110 light-years from our planet. Scientists speculate that Phecda might be accompanied by an exoplanet, a colossal gas giant with a diameter 80 times larger than Jupiter.

The star’s mass is four times greater than that of the Sun, and its radius is approximately the same multiple times larger than the Sun’s. The star is estimated to be around 320 million years old and has a temperature of about 9500 °K.

Megrez

Megrez is a star in the constellation Ursa Major that forms part of the Big Dipper. It has a brightness of 1.4, making it easily visible to the naked eye. In Arabic, its name translates to “base of the tail,” referring to its position in the constellation. Megrez is larger and more massive than our Sun, with a mass 2.5 times that of the Sun and a radius about twice as large. It is also much hotter, with a photospheric temperature exceeding 8500 degrees Kelvin. Megrez is relatively young, with an estimated age of just under 400 million years.

The distance between Earth and Megretz is more than 80 light-years. It is the least bright star in the constellation Ursa Major.

Aliot

Aliot is an epsilon star in Ursa Major. Its distance from Earth is approximately 80 light-years. It is the most luminous star in the Big Dipper. Its mass is 2.91 times that of the Sun, and its radius is four times larger. The surface temperature of this celestial body is heated to 10800 degrees Kelvin.

The celestial body belongs to the category of hot white subgiant. Its name signifies “cheese curd”.

Mizar

Mizar is the zeta star of the Ursa Major constellation. It is positioned as the second star from the tip of the “handle of the Big Dipper”. In Arabic, it translates to “belt”. Its estimated distance from our planet is around 78 light years. Individuals blessed with exceptional eyesight can spot another star in close proximity to Mizar known as Alcor. The ability to discern this star serves as a test for visual acuity.

Mizar is a binary star. Its apparent magnitude is slightly above 2. The combined mass of the two stars is approximately twice that of our Sun.

Alkaid, also known as Benetnash.

This star is the third brightest in the constellation Ursa Major. Its name translates to “leader of the mourners.” Alkaid is located at the tip of the “handle” of the Big Dipper. Interestingly, it is one of the hottest stars visible to the naked eye, without the need for telescopic aids. Benetnash has a surface temperature of 22000 degrees Kelvin. It is located over 100 light years away from Earth.

The state of Alaska has chosen to represent the constellation Ursa Major, also known as the Big Dipper, on its flag.

Celestial Bodies Beyond Our Galaxy

The Ursa Major constellation is home to various distant celestial objects that captivate astronomers. Among these are the renowned Messier galaxies.

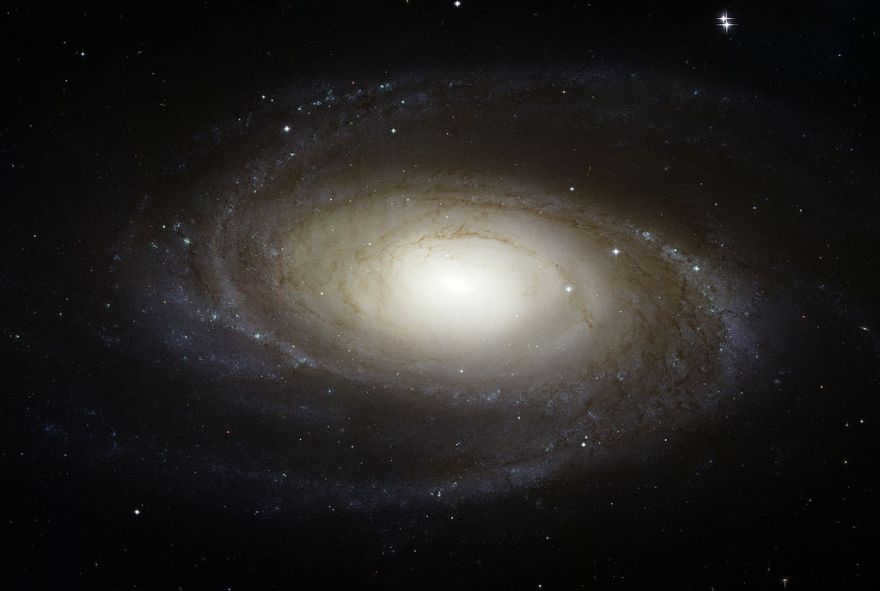

The Bode Galaxy (M81)

The Bode Galaxy, also known as M81, is a brilliant spiral galaxy situated approximately 11.8 million light-years away from our planet Earth. Notably, it holds the distinction of being the closest galaxy to the Local Group. With its regular shape and prominent arms stretching towards the center, the Bode Galaxy exhibits a captivating appearance. Its distinguishing feature is its radiant brightness, which contributes to its awe-inspiring allure. The Bode Galaxy was initially identified by the esteemed scientist I. Bode in the year 1774, solidifying its place in astronomical history.

A significant portion of the galactic radiation that is observable in the infrared spectrum emanates from cosmic dust within the Bode Galaxy. This cosmic dust is primarily concentrated within its spiral arms and is intrinsically linked to the various processes of star formation occurring within the galaxy. Remarkably, the Bode Galaxy is estimated to house a staggering minimum of 250 billion stars within its expansive boundaries. Moreover, nestled within its core lies an enormous black hole, boasting a mass that surpasses that of our solar system by a staggering 70 million times.

Astronomers have successfully detected a supernova SN1993J in the Bode galaxy. This galaxy is gravitationally interacting with the galaxies M 82 and NGC 3077, resulting in the formation of thread-like structures between them. Through these formations, astronomers are able to observe the process of interstellar gas being drawn into the centers of these galaxies, indicating active star formation processes.

The Bode galaxy can be observed with binoculars, where a small bright spot will be visible. However, with more powerful telescopes, the boundaries and core of this star cluster can be seen by the naked eye.

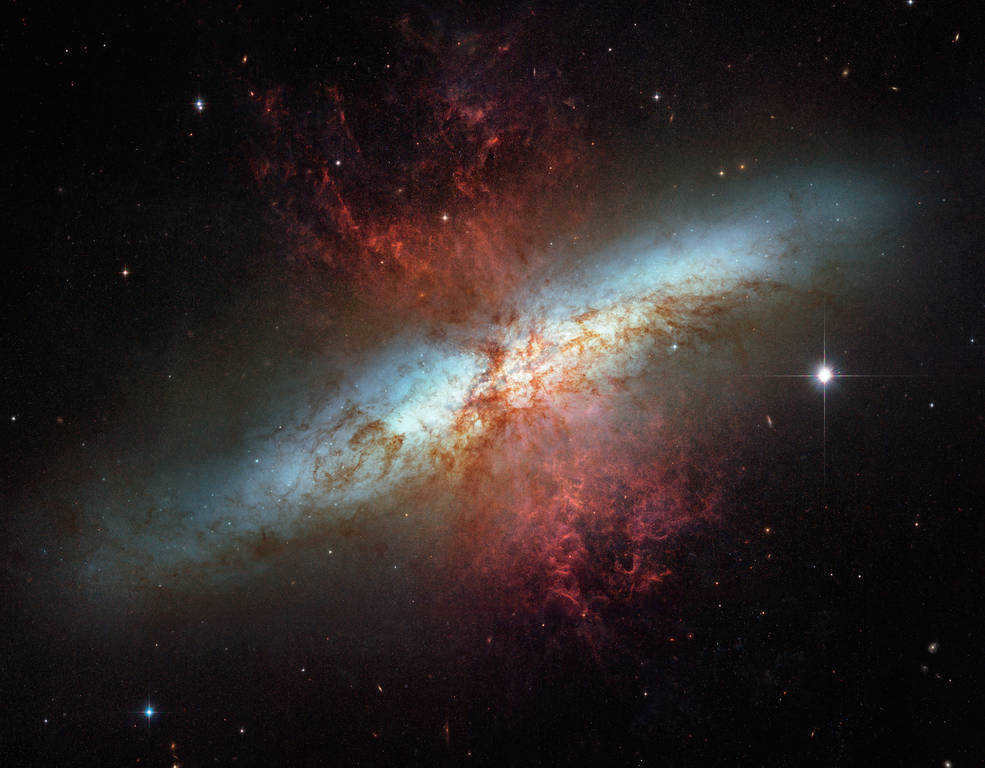

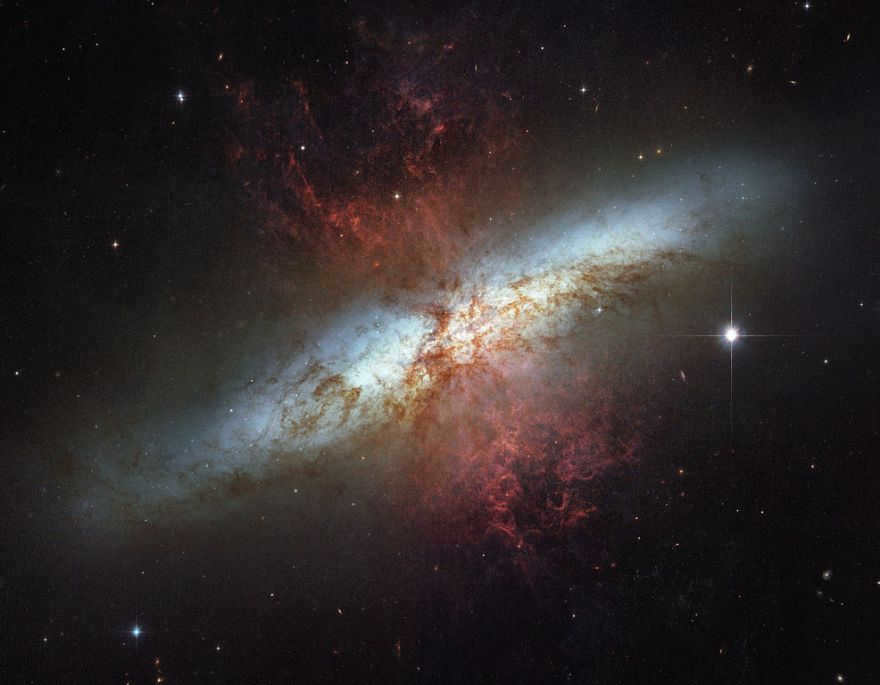

Cigar Galaxy

Also known as M82 and NGC 3034, the Cigar Galaxy is situated 12 million light years from Earth. Its peculiar elongated structure earned it this unique moniker. Infrared observations have revealed that the galaxy boasts two spiral arms. At its core lies a massive, voluminous entity – an enormous black hole that outweighs the Sun by a staggering 30 million times.

The Big Dipper galaxy interacts with its neighboring Bose galaxy. Observations indicate the presence of active star formation pockets within it. Additionally, it is the location where the supernova SN 2014J was discovered.

When observing the night sky using binoculars, one can perceive the galaxy as a slender rod. However, to observe the nucleus and dark spots of this cluster, a telescope is necessary. The optimal time for observing the galaxy is during the spring season.

Within the constellation of Ursa Major, there exist numerous other galaxies. The nearest star cluster is approximately 7 million light years away.

The Owl Nebula

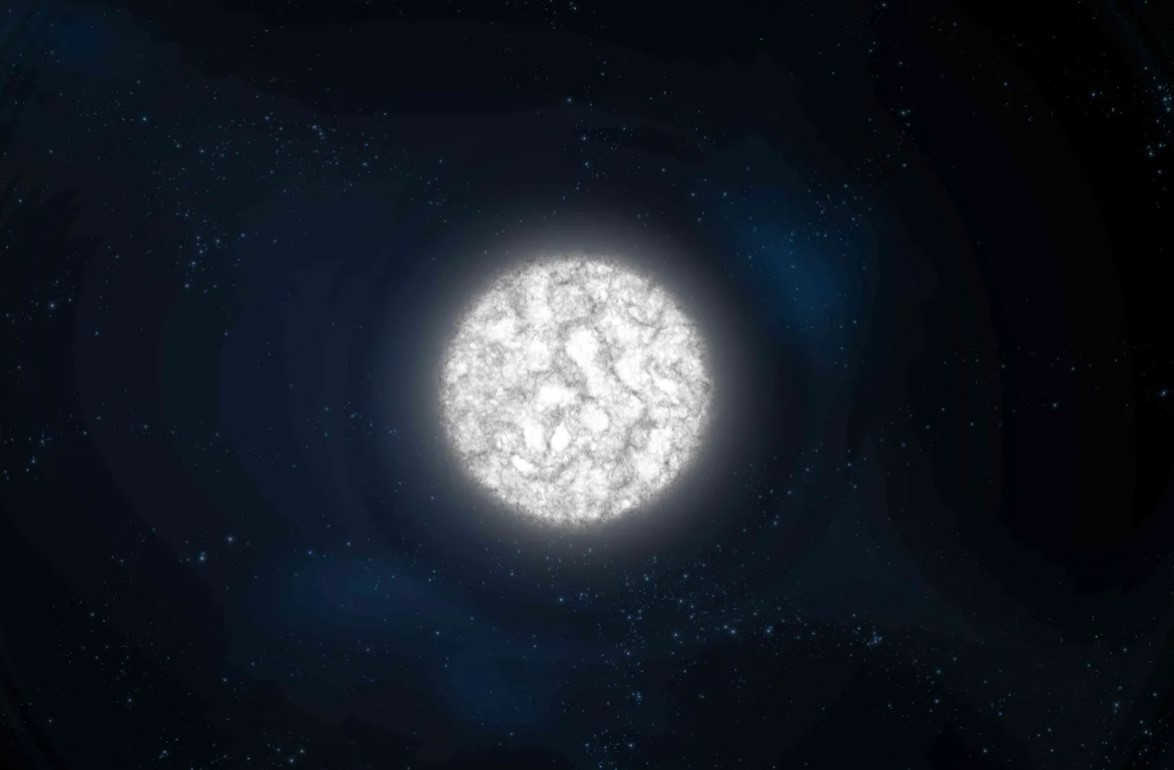

The Owl Nebula is situated approximately 2.6 thousand light years away. The central star of this celestial formation has a mass of 0.7 times that of our Sun, yet it possesses an astonishingly high surface temperature of 123 thousand Kelvin. Surrounding the star, one can find helium, hydrogen, nitrogen, and a small quantity of sulfur. In total, the mass of this gaseous structure is about 7.5 times lighter than our Sun.

The nebula is estimated to be around 8 thousand years old. The central star has depleted its hydrogen and has transformed into a white dwarf. During the collapse of the red giant, the outer shell was expelled in two directions, resulting in the ejection of matter. To an observer, these ejections appear as two “owl’s eyes”.

Amateur optical instruments are sufficient to observe the nebula. However, with a more powerful telescope, one can discern the “eyes” of this celestial object and the red halo surrounding it.

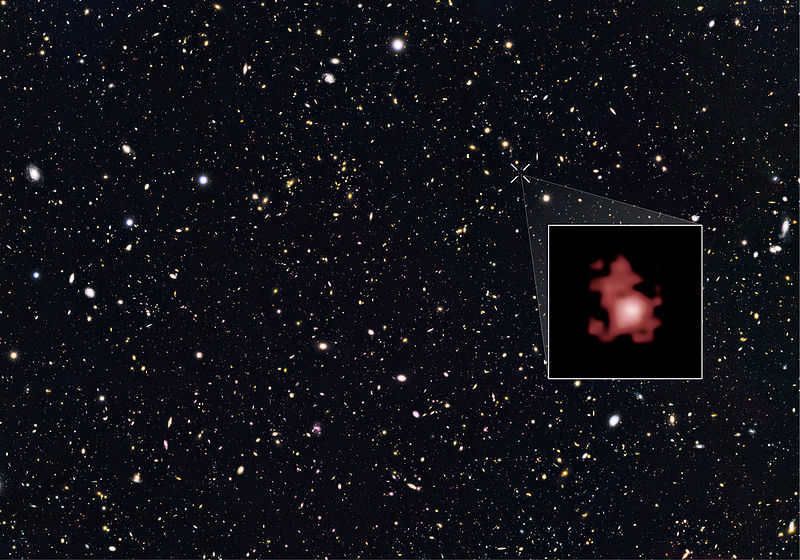

Galaxy GN-z11

In 2016, scientists made a groundbreaking discovery when they found a star cluster known as Galaxy GN-z11. The light emitted from this cluster took a staggering 13.4 billion years to reach Earth, a distance that is now estimated to be an unimaginable 32 billion light years away due to the expansion of the Universe. What’s even more mind-boggling is that the escape velocity of this galaxy is slightly less than the speed of light. Additionally, it has been determined that GN-z11 is a mere 25 times smaller than our very own Milky Way.

Until now, this galaxy holds the record for being the most remote celestial object from Earth. The other stars that make up the Big Dipper are much closer to our planet.

How the constellation was interpreted by various cultures

The Big Dipper is a constellation that has been known since ancient times. Different cultures and civilizations have observed and interpreted this constellation in various ways.

Egyptians and Their Fascination with the Stars

The ancient Egyptians were among the first civilizations in the world to take an interest in the stars. Some of their astronomical records date back 5,000 years, showcasing their early exploration of the cosmos. In fact, the Egyptians were the original discoverers of constellations, a system that continues to shape modern science.

During this time, the polar star, known as Alpha Dragon, held a special significance for the Egyptians. They believed that gods resided in its vicinity due to its stationary position in the sky. Rather than seeing it as a ladle, they perceived it as a “bull’s leg.” This was because Seth, the god of war and death, transformed into a bull and used his leg to kill Osiris. In retaliation, Horus, the son of Osiris, who possessed 40 heads, cut off Seth’s leg.

Chinese

Chinese astronomers partitioned the celestial sphere into 28 divisions. These divisions are traversed by the Moon during its monthly orbit around the Earth. Positioned at the heart of the celestial realm, where Polaris resides, is the Chinese emperor. In close proximity to the center lie the 7 most brilliant stars, enclosed within a boundary of purple hue. This boundary can also be described as a component of the Shandi Emperor’s chariot.

When it comes to size, the Big Dipper ranks among the largest constellations and holds the third position. Only Hydra and Virgo surpass it in terms of magnitude.

Indian Astronomers

Astronomy in ancient India had a development, although not as profound as mathematics, for instance. The knowledge of ancient Indian astronomers evolved under the influence from Greece and China. Consequently, scientists claim that the Moon passes through specific stations called nakshatras, with approximately 27-28 of them. This bears a striking resemblance to the study of stars in China.

Polaris held a special significance for the ancient Hindus. The Vedas’ authors believed that it was the abode of Vishnu himself. Moreover, the Big Bucket situated nearby served as the dwelling place for seven sages. These sages were born from Brahma, the deity who, according to ancient Indian mythology, is the progenitor of all life on Earth.

Ancient Greeks

As early as the 2nd century BC, Ptolemy’s star catalog included a total of 48 constellations. Among them, the prominent position was held by the Big Dipper. Homer also made reference to it, referring to the constellation as a “carriage”. The ancient Greeks perceived a bear in the sky, and this gave rise to numerous myths and legends.

America’s Native People

Legend has it that the Iroquois have a tale about three skilled hunters, represented by the three stars that form the handle of a bucket. Aliot is a hunter equipped with a bow and arrow. Mitzar is a hunter who carries the necessary tools for cooking meat (in fact, Alkor’s tail serves as a cauldron). Benetnash is a hunter responsible for gathering firewood.

In the autumn, the Big Dipper appears low on the horizon. According to ancient Iroquois legends, during this season, the blood of a wounded bear trickles down and stains the trees purple.

Locating the Big Dipper: A Beginner’s Guide

When it comes to finding constellations, it can be quite challenging without the help of astronomical equipment. However, there is one constellation that stands out from the rest – the Big Dipper. Its distinct shape makes it easily recognizable, even for those without any knowledge in astronomy.

During late summer and early fall, you can spot this asterism in the northern part of the sky. For the best experience, it is recommended to conduct amateur astronomical observations outside the city, ideally at midnight. This way, you can avoid any interference from the light emitted by cars and streetlights.

It’s important to note that the location of the Big Dipper changes due to the Earth’s rotation around the Sun. In winter, the handle of the “bucket” gradually starts to turn downward, while the entire constellation moves towards the northeastern part of the sky.

During the spring season, the position of the Big Dipper undergoes a change, making it challenging for those unfamiliar with the wonders of astronomy to locate it. This celestial formation can be found high in the sky, with the dipper facing west and the “handle” pointing towards the east.

Individuals residing in the northern regions face the greatest difficulty in spotting the stars of the Big and Little Bear during the summer months, when nights are considerably shorter.

Asterism Ursa Major

This asterism is highly recognizable in the nocturnal firmament. The arrangement of the Ursa Major constellation has been known since ancient times by various names – Elk, Plough, Cart, and others. The designations of the stars in the Ursa Major constellation trace back to Arabic origins.

Often, this asterism is mistakenly identified as the constellation itself. However, this is a fallacy: the Big Dipper is merely a segment of the constellation, encompassing the most brilliant celestial bodies. Ursa Major occupies a significantly larger portion of the celestial sphere.

The asterism is visible throughout the entirety of the Northern Hemisphere and a portion of the Southern Hemisphere (up to 30°S). In the majority of Northern Hemisphere regions, the Big Dipper never sinks below the horizon.

The asterism serves as a guide for locating Arcturus, Spike, Alphard, Capella, and Polaris. The Big Dipper is a helpful tool for easily locating the Leo, Ursa Minor, Hydra, Ascendant, and Gemini constellations.

Guide to Locating Polaris Using the Big Dipper

The leading star of Ursa Minor, commonly known as the Little Bear, serves as a reliable indicator of the north. Familiarizing oneself with this method allows for safe navigation during nighttime, even without a compass. Additionally, the star’s elevation above the horizon corresponds to the geographic latitude of the specific location.

Polaris is positioned directly above the North Pole. In other words, if an observer were to stand precisely at this point on the globe (with a latitude of 90 degrees), the star would appear directly overhead, situated in the zenith. Only at the North Pole does Polaris occupy the center of the sky. As one approaches the equator, however, the star’s elevation gradually decreases.

To locate Polaris, you first need to locate the distinctive dipper. The dipper is formed by two stars called Merak and Dubhe, with Merak at the bottom and Dubhe at the top. If you mentally trace the constellation of the Big Dipper, you will find its “handle” on the left and the wider part on the right. On the wider part, you will find two bright stars. Draw a line from the less bright star, Merak, to the brighter star, Dubhe. Polaris is located on this line. Polaris is very bright, making it difficult for an observer to mistake it for another star.

Getting Oriented with a Pail

By using the aforementioned method to locate Polaris, one can establish a vertical line towards the Earth. This line signifies the north direction. Once the north is determined, it becomes relatively easy to ascertain the other cardinal directions.

Optimal Times to Observe the Ursa Major

In regions with moderate latitudes, the Ursa Major can be observed throughout the year during all hours of the night. During the spring season, ideal conditions for stargazing are achieved, as the constellation is positioned high in the sky. The Ursa Major is also clearly visible during summer nights, although its visibility diminishes significantly in latitudes north of Moscow due to the persistent brightness of the sky. In the autumn, the Ursa Major is the least observable constellation.

Legends and myths surrounding the constellation

Throughout history, various cultures have developed mythical stories to explain the origin of the Big Bear constellation. One such tale comes from ancient Greece, where the constellation is connected to the tragic story of Callisto, a nymph who was the daughter of Lycaon, the ruler of Arcadia. According to the myth, Zeus, the king of the gods, seduced Callisto and they had a son named Arcades. When Zeus’ wife, the goddess Hera, discovered the affair, she became furious with Callisto and transformed her into a fearsome bear, stripping her of her beauty.

Arcades, unaware of his mother’s fate, encountered the bear in his home and attempted to shoot it with an arrow. Little did he know that the bear was actually his own mother in disguise. Zeus intervened just in time to prevent the tragedy and brought Callisto to the heavens, where she became the constellation Ursa Major. He also placed their son, Arcades, nearby, giving rise to the constellation Ursa Minor, also known as the Little Bear.

Hera’s vengeful actions against the estranged couple did not cease even after her demise. She implored Poseidon to prohibit the bears from venturing into the depths of the ocean, thus leaving them forever parched. However, the compassionate sea god relented and allowed them to dip beneath the horizon once per day. Ever since, the Great Bear and the Little Bear have journeyed through the night sky, serving as celestial guides.

Another fabled tale is also intertwined with Zeus. The tragic narrative unfolded immediately following the birth of the supreme deity. Cronus, his father, devoured all of his offspring to prevent them from usurping his throne. Zeus, the last-born son, was saved by his mother Rhea, who could no longer bear witness to her children’s demise. Rhea dispatched two female bears to Crete, where they nurtured Zeus until they were eventually transported to the heavens.

Fun facts about the Ursa Major

For those who love observing the night sky, here are some interesting tidbits about the Ursa Major constellation, also known as the Big Dipper.

- The star Southern Alula holds the distinction of being the closest star to Earth within the Ursa Major constellation, but it can only be seen through a telescope due to its distance of 29 light years.

- Exploring the area of the sky where the Ursa Major constellation resides can lead to the discovery of numerous fascinating celestial objects, including variable and double stars, galaxies, and planetary nebulae.

- In ancient times, the Ursa Major constellation served as a reliable and unwavering compass for seafarers. The Greeks relied on the stars within this constellation to navigate their ships, while the Phoenicians looked to the Little Dipper for more accurate guidance in determining the northern direction.

- In 2016, astronomers made an astounding discovery within the Ursa Major constellation – the star cluster GN-z11. This object holds the record for being one of the most distant known celestial bodies, with a mind-boggling distance of 13.4 billion light years.

- There is a star similar to the Sun with planets orbiting around it, suggesting the possibility of life.

The Big Dipper is easily identifiable in the night sky, even for beginners, and serves as a helpful navigational tool for finding the northern direction. Within this constellation, there are celestial objects that exist millions of light years away from our own cosmic home. The exploration of these objects in the future will aid in unraveling the mysteries surrounding the universe’s origin.

The Big Dipper, known by various names such as the Plow, Sapta Rishi, and Pot, is one of the most well-known asterisms. It is prominently located within the Big Dipper constellation and has been recognized in numerous cultures. Particularly in the summer, it is effortlessly visible in the northern sky and holds a significant place of recognition.

Many times, people confuse the asterism known as the Big Bucket with the constellation called the Big Dipper. However, it is important to note that the Kovsh is not an actual constellation, but rather just the most prominent section of it (the Big Dipper itself being the third largest constellation).

The Big Dipper constellation encompasses a significantly larger expanse compared to the asterism. However, the stars that comprise the head, torso, legs, and tail are not as bright as the seven brightest stars situated in the posterior and tail (asterism).

Stellar Constellation

The Big Dipper consists of seven prominent stars: Alcaid (Eta), Mizar (Zeta), Alioth (Epsilon), Megrez (Delta), Phad (Gamma), Dubhe (Alpha), and Merak (Beta).

The arrangement of stars in the Big Bucket asterism can be described spatially. Alkaid, Mitsar, and Aliot form the handle of the bucket, while Megrez, Fekda, Dubhe, and Merak form the bowl.

The brightest star in the Big Bucket is Aliot, which is also the brightest star in the constellation and the 31st brightest star in the sky. Five of the seven stars in the asterism belong to the Moving Group of stars in the Big Dipper (Collinder 285): Mizar, Aliot, Megrez, Fekda, and Merak. These stars have a common origin and exhibit similar motion and velocity in space.

Alcaide is a young blue main-sequence (B3V) star with a visual magnitude of 1.85 (the third brightest in the constellation) and located 101 light-years away. It is six times more massive than the Sun and shines 700 times brighter.

It is also known as Benetnash, which translates to “leader of the mourners” in Arabic. It is situated at the tip of the Bucket’s handle (the tip of the tail).

Mizar (derived from the Arabic word mīzar, meaning “belt”) is a double star consisting of two double stars. It has an apparent magnitude of 2.23 and is located 82.8 light-years away. It holds the distinction of being the first double star to be captured in a photograph in 1857.

Aliot, which means “thick tail of the sheep” in Arabic, is a star known as A0pCr. It has an apparent magnitude of 1.76 and is located approximately 81 light-years away. This star exhibits variations in its spectral lines over a period of 5.1 days. Among the 7 stars in the asterism, Aliot shines the brightest. Its position is in the tail, nearer to the body.

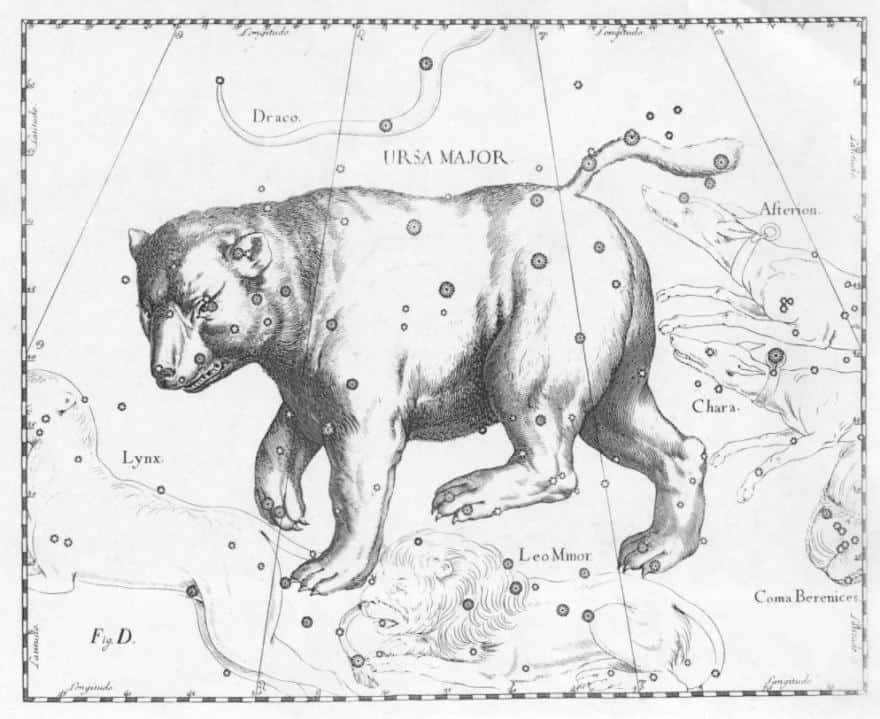

The Big Dipper constellation can be observed in Jan Hevelius’ Uranographia. It is depicted as a mirror image, showcasing the celestial sphere from an “outside” perspective.

Megrez, which translates to “base of the tail” in Arabic, is a white dwarf star in the main sequence (A3V). It has a visual magnitude of 3.312, making it the faintest among the seven stars in the constellation. Megrez is located at a distance of 58.4 light-years and has a mass 63% larger than that of the Sun. Additionally, it is 14 times brighter than our Sun.

Feqda, meaning “bear’s thigh” in Arabic, is another white dwarf star in the main sequence (A0Ve). It has an apparent magnitude of 2.438 and is located at a distance of 83.2 light-years.

Dubhe, which means “bear” in Arabic, is a bright orange giant star (K1II-III) with a visual magnitude of 1.79, making it the second brightest star in the constellation. It is located approximately 123 light-years away. Dubhe is actually a binary star system, consisting of a primary star and a companion star. The primary star is an orange giant, while the companion is a yellow-white main-sequence star (F0V). The two stars are separated by a distance of 23 astronomical units (a.u.) and have an orbital period of approximately 44.4 years.

Merak, which translates to “loincloth” in Arabic, is a white main-sequence star (A1V) with a visual magnitude of 2.37. It is located about 79.7 light-years away. Merak is also known as a variable star, meaning its brightness fluctuates over time. It has a mass that is 2.7 times that of the Sun and is about 68 times brighter.

Facts and Location

The constellation Ursa Major covers the second quadrant in the northern hemisphere (NQ2). It can be found at latitudes ranging from +90° to -30°. The best visibility is provided in April. The asterism is visible all year round in most regions of the northern hemisphere (it never falls below the horizon). Due to the rotation of the Earth, the constellation appears to slowly move counterclockwise around the north celestial pole.

Throughout the year, the Big Dipper asterism can be seen in different parts of the sky. In the spring and summer, it is positioned high in the sky, while in the fall and winter, it appears closer to the horizon. The appearance of the asterism can vary significantly. For example, in the fall, it seems to rest on the horizon, in the winter, the handle extends out of the bowl, in the spring, it is upside down, and in the summer, the bowl is tilted closer to the ground.

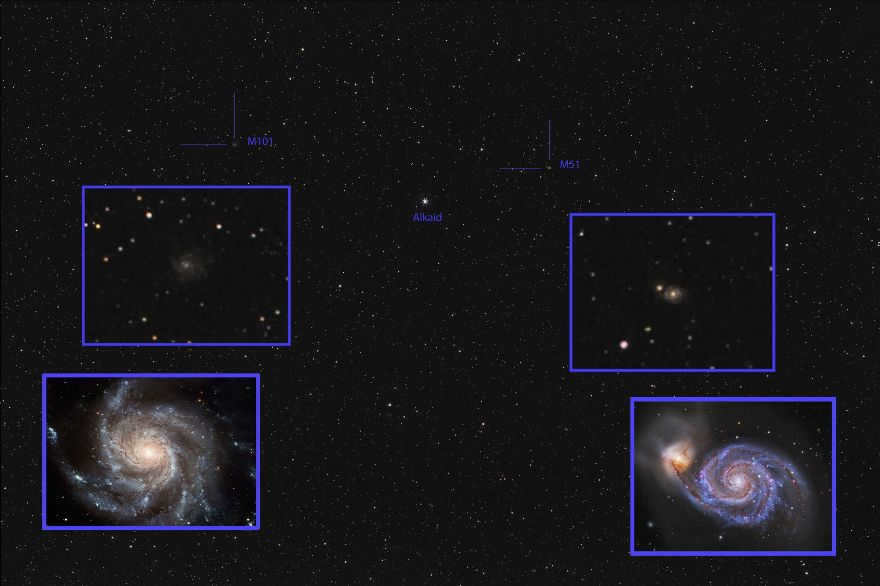

The asterism known as The Big Bucket and the galaxies M51 and M101 can be found in close proximity to each other. Situated in this region are a number of other significant celestial objects, including the Whirlpool Galaxy (Messier 51), the Whirlpool (Messier 101), the double star Messier 40, the spiral galaxy Messier 81 (also known as the Bode Galaxy), the irregular galaxy Messier 82 (referred to as the Cigar), the planetary nebula Messier 97 (commonly called the Owl Nebula), and the spiral galaxies Messier 108 and Messier 109.

The asterism within the Big Dipper constellation plays a crucial role in the identification of other prominent stars. By following the handle, one can locate Arcturus in the constellation Capricorn, and by extending the line further, the star Spica in Virgo can be found. The two stars that form the bowl of the Big Dipper point directly to Polaris, the North Star, while Megrez and Thekda indicate the location of Regulus in Leo, which happens to be one of the brightest stars in the night sky. Furthermore, Megrez and Dubhe align to lead the way to Capella in the Ascendant, and by following the path from Megrez to Merak and then to Castor, one can find this star in the constellation Gemini.

In 50000 years, the position of the stars in the Big Dipper will undergo a shift, resulting in a change in the configuration of the asterism (a reversal in direction). However, due to the fact that the majority of these stars belong to the Moving Group of stars in the Big Dipper (with the exception of Alkaid and Dubhe), the overall pattern will not experience a dramatic alteration. This pattern will continue to remain unchanged for another 100,000 years, although the handle will still undergo transformation.

To locate Polaris, you can visualize a line from Merak to Dubhe and mark this segment five times.

If you have already found the Big Dipper, it will only take a few seconds to find Polaris. It can be found in the Little Dipper constellation. The Big Ladle, which is a part of the Big Dipper, rotates around the North Pole and always points towards Polaris.

The Small Bucket is situated in close proximity to the Big Bucket. However, the stars in the Small Bucket are much dimmer, making them difficult to locate, particularly in areas with heavy city lights. As a result, it is more convenient to rely on the stars in the Big Bucket, which will assist you in finding Polaris and the North. To do so, simply trace a path from the stars Merak and Dubhe, located at the end of the Big Bucket’s bowl. Continue along this line until you encounter a brilliant star, known as the pointer stars. Additionally, after locating Polaris, you can also spot the Small Bucket, as its star is positioned at the end of its handle (or tail).

Legend

The constellation of the Big Dipper has been the subject of various legends and folk tales from different cultures. In Hindu mythology, it is referred to as Sapta Rishi, which translates to Seven Great Sages. In East Asia, it is known as the Northern Bucket, while in China it is called Zeih Sing. Malaysia refers to it as Burudj (Biduk), and in Mongolia, it is known as the Seven Gods. In Arabic history, the stars forming the bowl were believed to represent a coffin, with the three stars symbolizing mourners following it. The name Alkaid is derived from this tale.

In Britain and Ireland, this constellation is commonly known as the Plow and occasionally referred to as the Butcher’s Knife in the northern parts of England. In the past, it was called Charles Wayne (wagon) in England. Interestingly, the Big Dipper is associated with the male gender, while the Small Dipper is associated with the female gender.

The Great Cart is known to the Slavs and Romanians, while the Germans refer to it as the Great Wagon. According to Roman mythology, they believed that “seven oxen” led the way, with two stars representing the bulls and the remaining stars symbolizing the cart. Certain Native American tribes have their own interpretation, describing three hunters in pursuit of a bear, which signifies the arrival of autumn and explains the reddening of leaves. Interestingly, the leaves appear stained with the bear’s blood due to its wounds, causing the asterism to be positioned lower than usual during this time.

Notably, the asterism held significance for black slaves in the United States as well, who sought a path to the north where freedom awaited. A song titled “Follow the Drinking Gourd” provided instructions to follow the Big Bucket, which served as a guide. In Africa, the asterism was referred to as the drinking gourd, and this designation and name eventually migrated to Canada and America.

Examine a photograph of the Big Dipper asterism in the constellation Ursa Major. Utilize our website’s star map to aid in your search or utilize online 3D models to explore additional asterisms, constellations, and the brightest stars in the galaxies.

The Big Dipper is a constellation situated in the northern sky, and its Latin translation, “Ursa Major,” means “great bear.”

The Big Dipper is the largest constellation in the northern sky and ranks third overall. Its prominent stars form a recognizable asterism known as the Big Dipper, which can be seen in the photograph available on our website. It has been recognized in various cultures, giving rise to numerous myths. It was also documented in Ptolemy’s catalog in the second century.

Legend

The Great Bear is not just a vast group of stars but also an incredibly ancient constellation, referenced as far back as Homer in the Bible. There exist countless narratives and fables from different cultures. According to ancient Greek mythology, it was believed to be Callisto, an exquisite nymph who swore an oath of abstinence in the sanctuary of Artemis. However, Zeus became enamored with her, seduced her, and she bore a son named Arcas.

After discovering the truth, Artemis decided to exile Callisto. However, Hera, Zeus’ wife, was furious about the betrayal and took matters into her own hands. She transformed the nymph into a bear as punishment. For 15 years, Callisto lived in the forest, disguised as a bear and hiding from hunters. Eventually, Arkas, her son, grew up and they unexpectedly crossed paths. Startled, Arkas reached for his spear, but Zeus intervened just in time and whisked them both up into the sky. This turn of events only fueled Hera’s anger. She pleaded with Oceanus and Thetis to prevent the bear from swimming in the northern waters. As a result, the Big Dipper is always visible in the northern latitudes, never setting below the horizon.

According to an alternative account, Artemis was responsible for the retribution. Following many years, Callisto and Arcas were apprehended together and presented as a gift to King Lycaon. However, they managed to escape and sought refuge in the sanctuary of Zeus. The deity came to their aid and elevated them to the celestial realm.

There is also a divergent legend surrounding Adastrea. She served as a nymph who nurtured Zeus during his infancy. In light of the prophecy that his father Cronus would be overthrown by his own offspring, he proceeded to eliminate all of his children. Yet, Rhea (his mother) managed to substitute a stone for Zeus and thus saved the baby. Adastrea, together with Ida, provided sustenance and care for him, and in gratitude he granted them ascent to heaven.

The Romans named the group of stars known as the Big Dipper “Septentrio” – meaning “the seven plows of oxen” – even though only two of the stars actually showed oxen, while the others appeared as carts. The Big Dipper has been seen as various animals, such as a camel, a shark, and a skunk, as well as objects like a sickle, a cart, and a canoe. In Chinese culture, the seven stars are referred to as Qih Xing, which honors the government. In Hindu mythology, they represent the seven sages, and the constellation is called Saptarshi.

In certain Indian legends, the Big Dipper was seen as a large bear, and the stars were believed to be warriors who announced a hunt for it. As the constellation appears lower in the sky during the autumn season, it is believed that the leaves turn red because of the blood dripping from the bear’s wounds.

In more recent American history, the constellation was seen as a symbol of the Underground Railroad, which enslaved individuals used to navigate their way to freedom in the north. Many songs were sung by freedmen as they journeyed south, dreaming of a new life.

Interesting information, whereabouts, and visual representation

The constellation known as the Big Dipper, which occupies a space of 1,280 square degrees, holds the distinction of being the third largest constellation. It is located in the second quadrant of the northern hemisphere (NQ2) and can be observed at latitudes ranging from +90° to -30°. This constellation shares borders with neighboring constellations such as the Wolf, Giraffe, Veronica’s Hair, Dragon, Lion, Lesser Lion, Hound Dogs, and Lynx.

Notably, the Big Dipper boasts the presence of 7 Messier objects, namely Messier 40, Messier 81 (NGC 3031), Messier 82 (NGC 3034), Messier 97 (NGC 3587), Messier 101 (NGC 5457), Messier 108 (NGC 3556), and Messier 109 (NGC 3992).

Additionally, it houses 13 stars that are accompanied by planets. The most brilliant among them is Epsilon, which belongs to the constellation of the Big Dipper and boasts an apparent magnitude of 1.76. Furthermore, there are two meteor streams known as the Alpha Ursa Majorids and the Leonids-Ursids. This particular constellation is a member of the Big Dipper cluster, along with other constellations such as the Wolf, Giraffe, Hound Dogs, Veronica’s Hair, Dragon, Little Lion, Lynx, Little Bear, and the Northern Crown.

Main stars

Have you observed the appearance of the Big Dipper constellation in the night sky? Now, let’s explore its stars and the famous asterism it forms.

The Big Dipper is an easily recognizable pattern of stars that can be seen in the night sky and has been observed and named in various cultures. Furthermore, it is also a handy tool for navigation as it points towards Polaris, which is a part of the Little Dipper constellation.

If you trace an imaginary line from Merak to Dubhe and continue following the arc, you will eventually reach Polaris.

Similarly, the Big Dipper is also known as the Plough and is a prominent asterism in the northern sky. It is easily recognizable for its distinctive shape, which resembles a ladle or a saucepan.

Consisting of seven stars, the Big Dipper is composed of Dubhe (Alpha), Merak (Beta), Fekda (Gamma), Megrez (Delta), Aliot (Epsilon), Mitsar (Zeta), and Alkaid (Eta). These stars are part of the Ursa Major constellation and are often used as a navigational tool.

Aliot, also known as Epsilon of the Big Dipper, is the brightest star in the constellation. It has an apparent visual magnitude of 1.76 and is located approximately 81 light-years away from Earth. With its fluctuating spectral lines, Aliot resembles a variable of the Alpha-2 Hound Dog type and is ranked as the 31st brightest star in the night sky.

It belongs to the Moving Group of stars in the constellation of the Big Dipper (with a common velocity and origin). In 1869, the group was discovered by Richard A. Proctor, an astronomer from England, who hypothesized that all the stars in the constellation, except Alcaide and Dubhe, share a similar proper motion, moving towards a point in the Sagittarius constellation.

The traditional name of the star is derived from the Arabic word “alyat,” which means “thick tail of a sheep” (referring to the star’s position in the tail of a bear).

Dubhe, also known as Alpha of the Big Dipper, is a double star with a spectroscopic nature (K1 II-III), having an apparent magnitude of 1.79 and located 123 light-years away. Its companion is a main-sequence star (F0 V) with an orbital period of 44.4 years and a distance of 23 astronomical units.

The star is part of a four-star system, with a binary system located at a distance of 900,000 astronomical units from the main pair.

The term “dubb” comes from the Arabic language and means “bear”. It does not belong to the Moving Group of stars in the Big Dipper.

Merak (Beta of the Big Dipper) is a main-sequence star (A1 V) with a visual magnitude of 2.37 and a distance of 79.7 light-years. It has a dusty disk that makes up 27% of Earth’s mass.

This star is 2.7 times more massive than the Sun, 2.84 times larger in radius, and 68 times brighter. It is part of the Moving Group of Stars in the Big Dipper and is considered to be a variable star.

The Arabic translation of its name is “loins”.

Alcaid (Eta Major) is a youthful star positioned on the main sequence (B3 V) with a visual magnitude of 1.85 and a distance of 101 light-years. It stands as the third most luminous star in the constellation and the 35th brightest among all stars. Situated on the far eastern side of the asterism, it shines with a naked eye visibility despite its incredibly high surface temperature of 20000 K. With a mass of 6 times that of our Sun and a brightness 700 times greater, Alcaid does not belong to the Moving Group of stars of the Big Dipper.

Despite its brightness ranking, it received the name “Eta” from Bayer, who named the stars in order from west to east. The name was derived from the Arabic phrase qā’id bināt na’sh, which translates to “leader of the daughters of the pier”.

Feqda, also known as Gamma of the Big Dipper, is a main-sequence star (A0 Ve) located 83.2 light-years away. It has a visual magnitude of 2.438 and is characterized by a gas envelope that contributes emission lines to its spectrum. This star is estimated to be around 300 million years old. Feqda is situated as the lower left star in the Bucket constellation and is separated by a distance of 8.5 light-years from the Mizar-Alcor system. It belongs to the Moving Group of the Big Dipper.

The name Feqda originates from the Arabic phrase fakhð ad-dubb, which translates to “thigh of the bear”.

Megrez, also known as Delta of the Big Dipper, is a main-sequence star (A3 V) located 58.4 light-years away. It has a visual magnitude of 3.312 and is 63% larger than the Sun in terms of mass and 14 times brighter. Scientists have observed an excess of infrared emission from Megrez, indicating the presence of a debris disk orbiting around it.

Out of the 7 stars that shine brightly, this particular one is the least bright. The word “Megrez” is derived from Arabic and means “base”, specifically referring to the base of a bear’s tail.

Mizar (Zeta of the Big Dipper) is a system composed of two double stars, positioned second from the end. It has an apparent magnitude of 2.23 and is located 82.8 light years away. It holds the distinction of being the first double star to be photographed. This groundbreaking event took place in 1857, thanks to the efforts of American photographer and inventor John A. Whipple, as well as the astronomer Jord. Whipple and astronomer George P. Bond. The duo utilized a wet collodion plate and a 15-inch refractor telescope at the Harvard College Observatory. Bond also captured an image of the star Vega (Lyra) in 1850.

The name “Mizar” is derived from the Arabic word “mīzar”, which means “belt”.

Alcor, also known as the “Horse and Rider,” is a visual companion to Mitzar in the Big Dipper. It has a visual magnitude of 3.99 and is located 81.7 light-years away. In India, it is sometimes referred to as Sukha (“forgotten”) and Arundhati. In 2009, a binary system was discovered.

Alcor belongs to the Moving Group of stars in the Big Dipper, and it is located 1.1 light-years away from Mitsar.

The W system in the Big Dipper is a binary system consisting of closely orbiting stars with a period of 0.3336 days. These stars are so close that their outer envelopes are in direct contact. As a result, they periodically outshine each other and reduce in brightness. The system’s apparent magnitude ranges from 7.75 to 8.48, and its spectral class is F8V.

Alcor is the prototype for the W variables in the Big Dipper.

Messier 40 (M40, Winnecke 4, WNC 4) is a binary star system that exhibits fluctuations in apparent visual magnitude ranging from 9.55 to 10.10. It is situated at a distance of 510 light-years from Earth. The star system was initially documented by Charles Messier in 1764, as he was in pursuit of a nebula that had been previously identified by Jan Hevelius. Subsequently, in 1863, Friedrich August Theodor Winnecke made the discovery of this star system.

47 of the Big Dipper is classified as a main-sequence (G1V) star, possessing an apparent magnitude of 5.03 and located at a distance of 45.9 light-years. It serves as a solar analog, sharing similarities in terms of mass, albeit slightly hotter and containing 110% of the iron content found in the Sun.

In the year 1996, scientists detected the presence of a planet that is 2.53 times the size of Jupiter. Subsequently, two additional planets were discovered in 2002 and 2010.

Nu and Xi of the Big Dipper are referred to as the “first jump”.

Alula Nord (Nu of the Big Dipper) is an observable double star that can be seen with the naked eye. Its apparent magnitude is 3.490 and it is located 399 light years away. It is classified as a giant star (K3 III) with a radius 57 times that of the sun and is 775 times brighter. The name “Alula Borealis” originates from the Arabic word al-Ūlā, which means “first (leap)”, and the Latin word “Borealis”, meaning northern.

Alula South (Xi of the Big Dipper) is a star system that was discovered in 1780 by William Herschel. It consists of main-sequence dwarf stars (G0 Ve) with a combined magnitude of 3.79 (4.32 and 4.84), and is located 29 light-years away.

It is a variable RS Hound Dog star, which refers to close double stars with large spots caused by an active chromosphere. These spots cause the star’s brightness to fluctuate by 0.2 magnitudes.

Both objects in the Xi system perform as a spectroscopic binary and are accompanied by a low-mass companion. In 1828, Xi became the initial binary star whose orbit could be computed.

Nu and Xi are the first of three pairs of stars that were referred to as “gazelle leaps” by the ancient Arabs.

Taniyah North (Lambda) and Taniyah South (Mu) – the “second leap”

Lambda of the Big Dipper is a star (A2 IV – losing mass and transforming into a giant) with a visible magnitude of 3.45 and a distance of 138 light years.

Mu of the Big Dipper is a red giant (M0) positioned 230 light years away. It has a visual magnitude of 3.06. It is a semi-regular variable star that exhibits brightness fluctuations between 2.99 and 3.33. It is accompanied by a visual companion located 1.5 astronomical units away.

Talitha North (Iota) and Talitha South (Kappa) are the “third leap” stars.

Iota, a member of the Big Dipper constellation, consists of two double stars. The first star is a white subgiant (A7 IV) and is part of a spectroscopic binary system. It is accompanied by two stars with magnitudes of 9th and 10th. Initially, the two double stars were separated by 10.7 angular seconds, but now they are only 4.5 angular seconds apart. It takes approximately 818 years for the stars to complete one orbit around each other. The system is located 47.3 light-years away.

Kappa, another star in the Big Dipper constellation, is a double star. It is composed of two A-type main-sequence dwarfs with visual magnitudes of 4.2 and 4.4. The combined apparent magnitude of the system is 3.60. Kappa is situated at a distance of 358 light-years.

Muscida, also known as Omicron of the Big Dipper, is a multiple star system. It consists of a G4 II-III star, which falls between a giant and a bright giant in terms of its classification. The system has an apparent visual magnitude of 3.35 and is located 179 light-years away. The traditional name of Muscida translates to “muzzle”.

Groombridge 1830, a G8V subdwarf, is situated 29.7 light-years away from us. British astronomer Stephen Groombridge discovered and documented it in the early 19th century, with his findings being published in 1838.

During its discovery, it held the record for the star with the most significant proper motion. However, it eventually dropped to third place after Kapteyn’s star and Barnard’s star were found.

As a halo star, it moves in the opposite direction of the galaxy’s rotation. Typically, halo stars like Groombridge 1830 have low metal content due to their formation during the earlier stages of the galaxy. Most halo stars are found either above or below the galactic plane and are approximately 10 billion years old. They possess highly eccentric orbits and travel at high cosmic velocities.

Laland 21185 is a red dwarf (M2V) with a visible brightness of 7.520 (unattainable without technology) and a distance of 8.11 light years. It is the fourth nearest star system to our own, following Alpha Centauri, Barnard’s Star, and Wolf 359. In 19900 years, it will approach as close as 4.65 light-years to the Sun.

It is classified as a BY Dragon variable and serves as a recognized source of X-ray radiation.

Psi of the Big Dipper is an orange giant (K1 III) with a visual brightness of 3.01 and a distance of 144.5 light years. It is referred to as Tian Zang or Ta Zun in Chinese, meaning “extremely honorable”.

Celestial objects

The Bode Galaxy (M81, NGC 3031) is a large spiral galaxy located 11.8 light-years away. It has a brightness of 6.94 on the apparent magnitude scale, making it a popular target for beginners and amateur astronomers.

With an apparent size of 26.9 x 14.1 angular minutes, the Bode Galaxy is quite impressive. In March 1993, astronomers observed a supernova known as SN 1993J within the galaxy.

Johann Bode, a German astronomer, first discovered the Bode Galaxy in 1774. Later, in 1779, Charles Messier re-identified it and added it to his catalog of celestial objects.

The Bode Galaxy is the largest galaxy in a group known as the M81 group, which consists of 34 galaxies. It is located 10 degrees northwest of the star Dubhe, which is part of the Big Dipper constellation.

Interactions with neighboring galaxies Messier 82 and NGC 3077 have had a significant impact on the Bode Galaxy. These interactions have caused the loss of hydrogen gas and the formation of gaseous filamentary structures. Additionally, the presence of interstellar gas has triggered star formation in the centers of Messier 82 and NGC 3077.

The Cigar Galaxy (M82, NGC 3034) is a galaxy that is seen edge-on and has a visible magnitude of 8.41. It is located at a distance of 11.5 million light-years.

In the core of this galaxy, the rate of star formation is 10 times higher compared to the rate of star formation in the entire Milky Way galaxy. Additionally, M82 is 5 times brighter. In 2005, the Hubble Space Telescope discovered 197 massive star clusters in the central region of M82.

M82 emits an excess of infrared radiation and stands out as the most luminous galaxy in the sky when observed in infrared light.

Scientists believe that M82 has undergone at least one tidal collision with Messier 81 in the past. As a result of this interaction, a large amount of gas has been funneled into the nucleus of M82, leading to a tenfold increase in star formation over the past 200 million years.

Johann Bode discovered this galaxy on December 31, 1774. He originally described it as a nebulous spot.

The Galaxy M82 is distinguished by its luminous blue disk, interlaced clouds, and blazing hydrogen feathers that burst forth from its core. In its central regions, young stars are born at a rate that is ten times faster than within the Milky Way. This phenomenon gives rise to an incredibly potent wind that compresses enough gas to produce millions of additional stars.

The Nebula of the Owl (M97, NGC 3587) is a celestial cloud with a visible brightness of 9.9 and a spatial separation of 2,600 light-years. Situated at its core is a star with a brightness of the 16th magnitude.

Pierre Mechene made the discovery of the nebula in 1781. It has an age of 8000 years. It acquired its moniker due to its resemblance to the eyes of an owl when viewed through a telescope.

Vertushka (M101, NGC 5457) is an observed spiral galaxy with a magnificent design. It has an apparent magnitude of 7.86 and is located 20.9 million light-years away. In August 2011, a Type Ia supernova (explosion of a white dwarf star) named SN 2011fe was discovered in this galaxy.

The galaxy was first discovered by Pierre Mechene in 1781 and later added to Charles Messier’s catalog. Mechene described it as “a nebula without a star, very obscure and quite large – 6′ to 7′ in diameter”.

Vertushka spans a diameter of 170,000 light-years, which is 70% larger than the Milky Way. It contains several large and bright H II regions, as well as hot newly formed stars.

NGC 5474, NGC 5204, NGC 5477, NGC 5585, and Holmberg IV are among the 5 companion galaxies believed to have influenced the creation of the grand design.

Messier 108 (M108, NGC 3556) is a spiral galaxy with a twist, discovered by Pierre Mechene in 1781. It appears to us nearly edge-on. Its apparent magnitude is 10.7, and it is located at a distance of 45,000 light-years.

It is a solitary member of the Ursa Major Cluster (part of the Virgo Supercluster). M108 is home to approximately 290 globular clusters and 83 X-ray sources.

A type 2 supernova, known as 1969B, was observed in 1969.

Messier 109 (M109, NGC 3992) is a gigantic spiral galaxy with a visual magnitude of 10.6 and a distance of 83.5 million light-years. It can be found to the southeast of Gamma in the constellation Ursa Major. In 1781, Pierre Mechene first spotted this galaxy, and two years later, Charles Messier included it in his catalog.

In 1956, astronomers discovered a Type Ia supernova named SN 1956A in M109. Additionally, there are three satellite galaxies associated with it: UGC 6923, UGC 6940, and UGC 6969.

Among the M109 group, this galaxy shines the brightest and is home to over 50 galaxies.

NGC 5474, a small galaxy positioned close to M101, is engaged in an interaction with it. It displays indications of spiral structure. Its visual magnitude is 11.3, and its distance is 22 million light-years.

As a result of tidal interactions with M101, the galaxy’s disk is shifted away from its core, leading to the initiation of star formation. If you utilize our 3D models and online telescope, you can examine the Big Dipper constellation more closely. For a do-it-yourself search, a static or moving star map will work just fine.

The notion of a dwarf galaxy may imply something minuscule, but don’t be fooled. NGC 5474 harbors billions of stars! Nevertheless, when compared to the vast number of stars in the Milky Way (which amounts to hundreds of billions), NGC 5474 does seem comparatively small. It is a member of the M101 group, with the brightest galaxy being Vertushka (M101)

Children in the 2nd grade are introduced to the Big Dipper, a constellation, during their study of “The Environment”.

It is crucial for students to learn how to locate the star formation known as the “bucket” in the nighttime sky, as it serves as a guide for locating various other celestial entities.

Description of the Ursa Major constellation

The Ursa Major constellation, also known as the Big Dipper, is one of the largest constellations in the northern hemisphere. It is named after a prominent feature it resembles – a big ladle with a long handle. This constellation is visible in the northern hemisphere and is a popular sight for stargazers.

Throughout Eastern Europe and Russia, the Big Bear constellation can be observed year-round (except for autumn in the southern regions of Russia, when the constellation is too low on the horizon). The best time to see it is in early spring.

The Big Dipper has been known to humanity for centuries and holds great significance in various cultures. It is mentioned in the Bible and Homer’s epic “Odyssey,” and its description can be found in the works of Ptolemy.

Ancient civilizations associated the star formation with various objects, such as a camel, a plow, a boat, a sickle, and a basket. In Germany, this constellation is known as the Great Basket, while in China, it is referred to as the Imperial Chariot. The Dutch people call it the Pot, and in Arab countries, it is known as the Grave of the Mourners.

How many stars are present in the Big Dipper constellation? There are a total of seven stars, each with fascinating names in different nations. The people of Mongolia refer to them as the Seven Gods, while the Hindus call them the Seven Sages.

According to Native American beliefs, the three stars that form the “handle of the bucket” represent three hunters chasing a bear. The alpha and beta stars of this constellation are also known as “pointers” because they help locate Polaris easily.

The changing position of the Big Dipper’s bucket throughout the seasons

Throughout the year, the Big Dipper’s bucket appears in different positions relative to the horizon. To navigate more effectively, it is advisable to utilize a compass.

During a clear spring evening, the group of stars can be found directly above the observer. Starting from mid-April, the “dipper” starts its westward movement. Throughout the summer, the constellation gradually shifts towards the northwest, descending. By the final days of August, the stars become visible in the northern sky, positioned as low as possible above the horizon.

In the autumn sky, one can witness the slow ascension of the constellation, while during the winter months it moves towards the northeast, as demonstrated in the diagram below, eventually rising once again by spring, reaching its highest point above the horizon.

To easily find the constellation, keep in mind that during summertime it can be found in the northwest direction, in the autumn it is located in the north, in winter it can be seen in the northeast, and during spring it is positioned directly above the observer.

The position of the stellar figure in the constellation of Big Bear changes depending on the time of day. Not only does it change relative to the celestial vault, but it also rotates on its own axis. The image above illustrates this phenomenon. In the evening during January and February, the “bucket” part of the constellation is located in the northeast (as seen in the picture on the right), with its “handle” pointing downwards.

As the night progresses, the constellation moves in a semicircle and eventually reaches the northwest by morning (as shown in the picture on the left), with the “handle” pointing upwards.

During July and August, these diurnal changes are opposite. The same opposite changes can also be observed during the spring and fall months.

The arrangement of the constellation in the celestial sphere is determined by its diurnal change, which varies according to the different seasons of the year.

The Stars that Comprise the Big Dipper

When considering the number of stars that make up the Big Dipper, it is the 7 most notable stars that are typically referenced. These 7 stars form the distinct shape of the “bucket” and are easily visible in the nighttime sky.

However, the constellation is actually more expansive, encompassing additional celestial bodies. The paws and face of the “bear” are comprised of stars with lower levels of brightness.

There are seven primary stars that constitute the constellation:

- Dubhe (the alpha star of the constellation, the second brightest. It serves as one of the two guides to the North Pole. Dubhe is a red giant located 125 light-years away from Earth.

- Merak (which means “lumbar” in English) is a beta star and the second guide to the North Pole. It is located approximately 80 light-years away from Earth, slightly larger than the Sun, and emits a strong stream of infrared radiation.

- Fekda (“hip”) is a small star that emits gamma rays and is located approximately 85 light-years away from Earth.

- Megrez (derived from the Arabic word for “base”) is a blue dwarf star that is more than 80 light-years away from our planet. It is called Megrez because it serves as the base of the extended tail of the celestial beast.

- Aliot (meaning “tail”) is an epsilon star, which is the brightest point in its constellation. It ranks 31st in terms of luminosity among all visible objects in the sky, with a stellar magnitude of 1.8. Aliot is a white star that shines 108 times brighter than the Sun. It is also one of the 57 celestial objects used for navigation purposes.

- Mizar (derived from the Arabic word for “belt”) is a zeta star, and it is the fourth brightest star in its cluster known as the “bucket”. Mizar is a double star system, and it has a dimmer companion called Alcor.

- Alcaide (also known as “leader”) or Benetnash (commonly referred to as “weeping”) is an eta-star, ranking third in terms of luminosity. It marks the end of the constellation Ursa Major’s “bear tail”. This celestial body is classified as a blue dwarf and is located approximately 100 light years away from Earth.

There are approximately 125 objects in total in the constellation.

Out of these, three pairs of stars that are located on the same line and at a short distance from each other are worth mentioning:

- Alula Borealis (nu constellation) and Alula Australis (xi),

- Taniya Borealis (lambda) and Taniya Australis (mu),

- Talitha Borealis (jota) and Talitha Australis (kappa).

These three pairs are also known as the three gazelle jumps, and they can be found at the bottom of the star cluster in the map below.

The diagram illustrates the positions of the main seven stars and objects from the Talitha, Tania, and Alula groups.

The Myth of the Big Dipper

There exists an age-old legend from Greece that provides insight into the origin of the name bestowed upon the Big Dipper constellation.

Callisto, the daughter of King Lycaon, was renowned for her exceptional beauty and served as a nymph in the court of Artemis. Captivated by her allure, Zeus assumed the guise of Artemis and seduced Callisto. Enraged by this betrayal, the true Artemis discovered Callisto’s pregnancy during a bath and promptly banished her. Heartbroken and alone, Callisto sought refuge in the mountains, where she eventually gave birth to her son, Arkas.