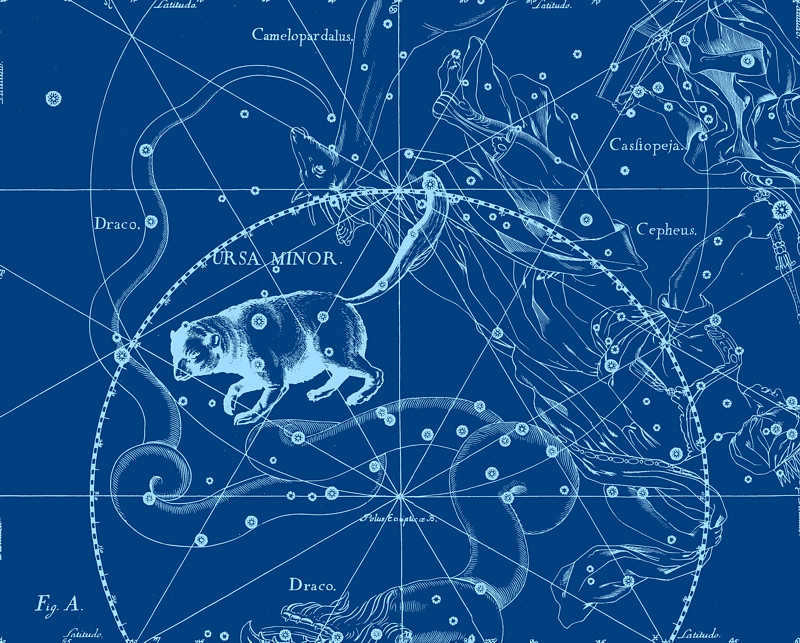

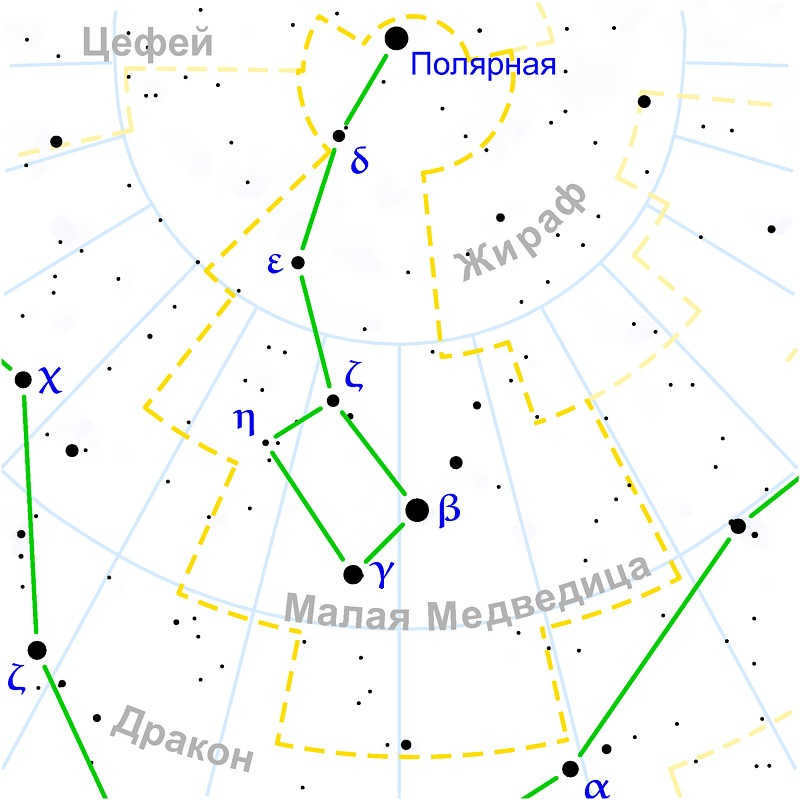

Polaris (Alpha Minor, α UMi) is the brightest star with a magnitude of +2.0 in the Little Bear constellation, which is situated near the North Pole of the Earth. Polaris is a supergiant and can be found at a distance of 447 ± 1.6 light-years (137.14 parsecs)[1][2].

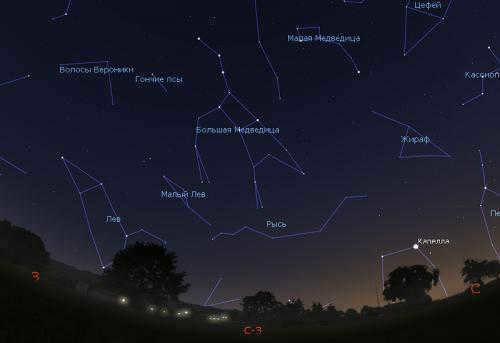

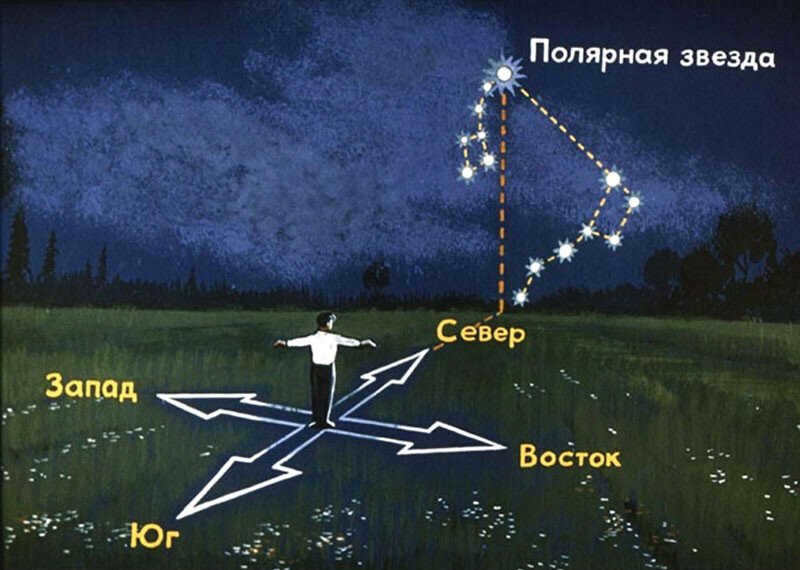

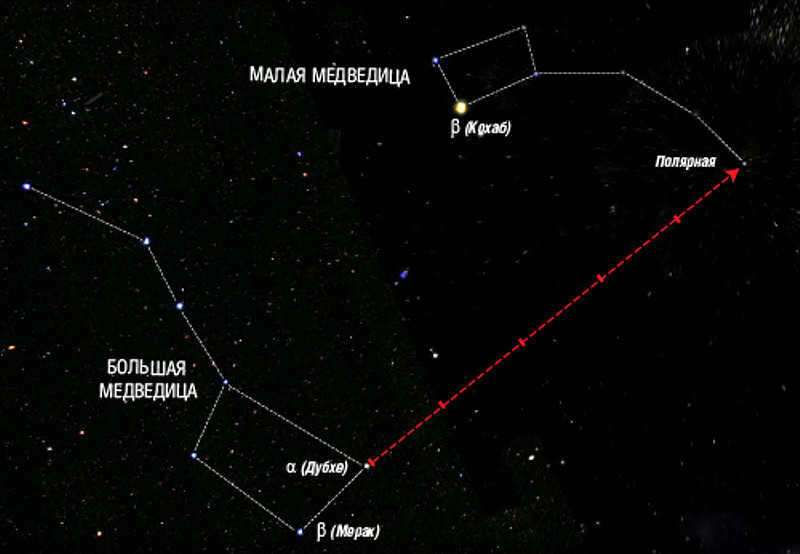

Polaris, also known as the North Star, is a key navigational tool in the Northern Hemisphere. It is always positioned above the northern point of the horizon, making it useful for terrain orientation. To locate Polaris, one must first identify the distinct arrangement of seven bright stars known as the Big Dipper. This constellation resembles a bucket, with two stars, Dubhe and Merak, forming the “wall” opposite the “handle.” By mentally drawing a line through these stars and extending it five times the distance between them, one can approximate the location of Polaris. Polaris is found approximately at the end of this line. The direction to Polaris aligns with true north, while its altitude above the horizon corresponds to the observer’s latitude.

Birds navigate based on the position of the Sun, factoring in its movement of 15 degrees per hour. In 1967, S.T. Emlen, an American zoologist, made an interesting observation about indigo finches. He found that these birds possess a star compass, allowing them to navigate at night by aligning themselves with the apparent movement of the starry sky. The birds are cognizant of the fact that all stars in the Northern Hemisphere revolve around Polaris. [6]

In the realm of fiction [ edit ].

At the request of his master, Leonardo summoned servants who transported the ailing individual to his sleeping quarters. Left alone, the artist proceeded to scrutinize Columbus’s mathematical calculations pertaining to the movement of Polaris near the Azores. To his astonishment, he uncovered such glaring inaccuracies that he couldn’t believe his own eyes. – What an astounding lack of knowledge! – he marveled. – It’s simply incredible that he stumbled upon a new world in the darkness, yet remains oblivious like a blind man, unaware of the true nature of his discovery, mistakenly believing it to be China, Solomon’s Ophir, or a terrestrial paradise. [7]

Each ataman possesses their own preferred points of good fortune, discovering them on the vast expanse of the open ocean, many versts away from the coastline, just as effortlessly as we locate a box of quills on our writing desk. All that is necessary is to position oneself in such a way that the North Star aligns perfectly above the bell tower of St. George’s Monastery, and then proceed in an uninterrupted eastward trajectory until the Foros lighthouse comes into view. [8]

Far-off snow-capped peaks glowed with a brilliant purple hue. Majestic swans gracefully soared above the fields to the north. On a misty evening, they perched at the pinnacle of the tower. Overhead, the tranquil North Star flickered. Their garments were a shade of gray, adorned with delicate silver-white lily blossoms. A gleaming blue cross adorned their chest. [9]

He came to the realization that, in this particular moment, she possessed greater strength than he did, and that a sensation unlike anything he had ever felt before was even more powerful than death itself. These eyes, he concluded, must possess the capacity to love, for who else should love if not these very eyes? Who else could he dedicate himself to other than the radiant sparkle of these magnificent eyes? If he were to love these eyes, then even one-sixth of the earth, captured in the sails of a ship, would not dare to defy the commanding hand that rests on the helm, confidently guiding the ship’s course. If the Polar Star were to illuminate the sky, serving as the guiding light for courageous captains, it would be impossible for any disobedience to arise.

– I believe we made a left turn.

– What makes you think that?

– When I went to see my dad, the hill was on our left, and now it’s on the right. They looked around more attentively, and Vasya proposed that they first locate the north using the North Star, and then determine their direction. However, they couldn’t spot either the Big Dipper or the usually bright, bluish Polaris. And just at that moment, the boys noticed that the sky had become darker and lower, the wind was blowing more frequently and with greater intensity, and everything seemed to have darkened around them. Their hearts filled with unease. [12]

My body trembled, engulfed by the frigid temperatures of the polar region. I was unable to find any warmth, as if trapped in an abandoned steel train amidst the vast, icy expanse of the Arctic Ocean. The thin, unheated hospital blankets provided no solace, only intensifying the bone-chilling cold. Above me, a thick curtain of northern lights danced with glimmering glass beads, adding to the intensity of the freeze. The Polar Star, a lone electric bulb, hung motionless, staring into my eyes with its feeble glow. It seemed to search, search, search, but could not meet my gaze with its deadly stare. In that moment, I experienced prophetic visions, fleeting yet unforgettable. And though most faded from memory, one left a faint imprint in my mind. [13]

– Hold on, I believe we have lost our way. We must determine our direction. The chairman turned onto his back and scanned the sky for Polaris.

– What’s the purpose of finding it? – Chonkin inquired.

– Don’t meddle,” Ivan Timofeyevich replied. – First, we locate the Big Dipper. And from there, it’s just two versts to the North Star. Where the North Star is, that’s where the north is.

– And the office is in the north? – Chonkin asked. [14]

We achieved, we triumphed, we accomplished an extraordinary feat. We finally arrived at the quaint taiga village of Mezhden. However, we had to endure countless challenges and rethink our plans in order to reach this destination. Just imagine what would have happened if we had chosen to aim for the majestic Polar Star instead. <.>

Regardless, I am determined not to lose Masha. After all, you can only lose something that you possess. And Masha is not something that I possess, she is a part of me. She will remain by my side, a guiding light like the Polar Star, its radiance shining upon the Earth for eternity, even if the star itself were to fade away. Furthermore, I did not choose to be with Masha for any selfish reasons, for then all the good in my life would be worthless. [15]

In the realm of poetry

As I gaze up towards the heavens, I witness a spectacle of vibrant flowers

Dancing and twirling in mesmerizing rainbows

Their radiant and golden features

Interweaving and interrupting one another

Until, all at once, they merge with the shimmering night sky

Can anything compare to the beauty of the northern lights?

Though they may vanish, their brilliance still shines through

Just like the steadfast polar star

For Virtue never abandons us, even in the darkest of times [17]

“Do you not hear?” the young man asks

“Can you not hear the melancholic wails of the youth?”

Do you not comprehend the profound meaning behind it?

It emanates from a distant place

Where the pillars stand, tainted with blood and engulfed in flames

Where the Polar Star

Trembles amidst the tearful moisture of the sky [18]

Her tent is situated amidst the snow and ice, while death looms over. The night extends for six months, with the pale Polar Star appearing motionless in the vast expanse of the sky. [19]

Sources [ edit ]

- ↑Scott G. Engle, Edward F. Guinan, and Petr HarmanecToward Resolving the Polaris Parallax Debate: An Accurate Measurement of the Distance to Our Closest Cepheid using Gaia DR2 (EN). The American Astronomical Society (July 16, 2018).

- ↑Astronomers have precisely determined the distance to Polaris (RU) (July 30, 2018).

- ↑Я. I. Perelman. "Fascinating Geometry in the Open and at Home". – L.: "Vremya", 1925.

- ↑T. Nikolaeva. "A Fresh Approach to Measuring Celestial Bodies". – M.: "In the Workshop of Nature," No. 6, 1927.

- ↑ 12By E. Kaurov and A. Lukyanov. “Ancient Chinese cosmography of the Tao culture”. – Published by “Problems of the Far East”, No. 10, 2002.

- ↑By Alexander Volkov. “Stories about animals, and not only about animals: Christian’s marvelous journey with wild geese”. – Published by “Znanie – sila”, 2003.

- ↑By D. S. Merezhkovsky. Collected Works in 4 Volumes. Volume I. – Published by Pravda, 1990.

- ↑By A. I. Kuprin. Collected Works in 9 vol. Volume 2. – Published by “Khudozhestvennaya Literatura”, 1971.

- ↑By Andrei Bely, “Old Arbat”: Stories. – Published by Moskovsky Rabochiy, 1989.

- ↑By G. V. Alekseev “Maria Hamilton”. – Published by Journal-Gazette Association, 1933.

- ↑Annenkov Y. P. “A Tale of Trivia”. – Moscow: Ivan Limbach Publishing House, 2001.

- ↑В. G. Melentiev. March 33. 2005. – Moscow: GIDL, 1958.

- ↑Kataev V.P. Trava zabvennya (The grass of oblivion). – Moscow, “Vagrius”, 1997.

- ↑Vladimir Voinovich. “Life and Adventures of the Soldier Chonkin”. – Moscow: Vagrius, 2000.

- ↑Ivanov A.V. “Geographer globus propyl”. – Moscow, Vagrius, 2003.

- ↑Mikhail Shishkin“Pismovnik” – M.: “Znamya”, № 7 for 2010.

- ↑Н. M. Karamzin. Complete collection of poems. Library of the poet. Big series. – L.: Soviet Writer, 1966.

- ↑ Poets of the 1790-1810s. Library of the Poet. Second edition. – L.: Soviet Writer, 1971.

- ↑I. Bunin. Poems. Library of the poet. – L.: Soviet Writer, 1956.

See also [ edit ]

- Wikipedia article

- Meanings in Wiktionary

- Texts on Wikiquote

- Media files on Wikimedia Commons

- News on Wikinews

Share the quotes on social media:

VKontakte – Facebook – Twitter – LiveJournal

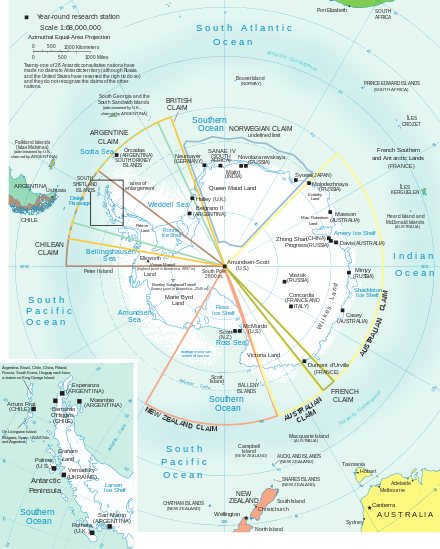

In the Southern Hemisphere

Antarctica territorial disputes

South Pole region

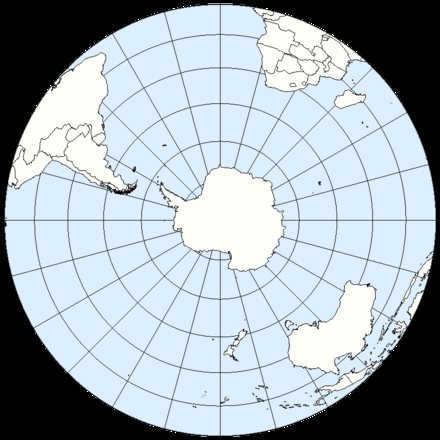

– The area of the globe situated to the south of the equator.

Characteristics

Summer in the Southern Hemisphere lasts from December through February, while winter lasts from June through August. In contrast to the Northern Hemisphere, the wind in cyclones in the Southern Hemisphere rotates in a clockwise direction due to the Coriolis force, while in anticyclones it rotates counterclockwise[1]. During astronomical noon, the Sun in the Southern Hemisphere, specifically south of the Southern Tropic (e.g., in New Zealand), is exactly north[2][3]. On the other hand, in the Northern Hemisphere, north of the Northern Tropic (e.g., in Russia), the Sun is exactly south. Consequently, for an observer in New Zealand, the Sun’s apparent path across the sky during the day is from right to left (when facing the Sun’s position at noon, i.e., north, with the back towards the south and the South Pole of the world)[4]. This is in contrast to Russia, where the Sun’s path is from left to right for an observer. If the observer is located between the tropics (for example, in Ecuador), the Sun’s path across the sky depends on the time of year. The noon Sun, closer to the day of the December solstice, will be in the southern part of the sky, while closer to the day of the June solstice, it will be in the northern part of the sky[3]. In the Southern Hemisphere, residents see the Moon “upside down”[5]. Consequently, it grows to the left and wanes to the right, whereas in the Northern Hemisphere, it is the opposite.

The starry sky in the Southern Hemisphere’s mid-latitudes differs greatly from that in the Northern Hemisphere’s mid-latitudes, particularly in terms of the constellations that can be observed. Additionally, there is no bright star equivalent to Polaris (which is near the North Pole and helps indicate the direction north) in the Southern Hemisphere. However, there is a constellation similar to the Big Dipper in the Northern Hemisphere that can be used to determine the direction to the South Pole. This constellation, known as the Southern Cross, is the most famous constellation in the Southern Hemisphere and the smallest in the night sky. By mentally extending the vertical “bar” of the Southern Cross upwards, at a distance approximately five times the length of the bar from its lower end, you will find the South Pole of the celestial sphere. The height of the South Pole above the horizon is equal to the observer’s southern latitude, and the direction to it indicates the direction to the South Pole[6]. The Southern Cross is so well-known that it is featured prominently on the national flags of Australia, Brazil (among eight other constellations and individual stars), New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, the flag of the New Zealand administered territory of Tokelau, and the flags of Australia’s Outer Territories – the unofficial Cocos Islands and the official Christmas Island. It is also found on the national emblems of Australia, Brazil, New Zealand, and Samoa.

The majority of the Southern Hemisphere is comprised of oceans and seas, in contrast to the Northern Hemisphere which is home to significant land masses. The population of the Southern Hemisphere represents around one-tenth of the global population. Some of the largest urban agglomerations in the world, such as Jakarta, São Paulo, Buenos Aires, Rio de Janeiro, and Kinshasa, are located in the Southern Hemisphere.

Geographically, the Southern Hemisphere includes four continents: Antarctica, Australia, most of South America (about nine-tenths), a portion of Africa, part of Asia (specifically the Malay Archipelago), a substantial number of islands in Oceania, and four oceans: the southern region of the Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans, as well as the entirety of the Southern Ocean.

One of the most incredible sights in the nighttime sky is a unique ribbon of translucent light extending diagonally across the celestial sphere. This is none other than the Milky Way

– our very own galaxy, the radiant glow of countless stars that travel enormous distances over tens of thousands, or even millions, of years to reach our eyes. Despite its spiral disk shape (with the solar system located at the end of one of its branches), it appears as a band when viewed from our perspective. The Milky Way is visible from both the northern and southern hemispheres, but its most brilliant section can be found in the southern constellation of

Sagittarius

.

Located millions of light-years away from Earth, all these celestial bodies cannot be observed with the naked eye. However, some galaxies like the Kiel Nebula and the Orion Nebula can be seen without special optics in their respective constellations. Advanced telescopes allow us to get a closer look at our neighboring galaxies, such as the NGC 2997 in the constellation of the Pump, revealing its gas and dust composition and countless stars.

The majority of star clusters in the Southern Hemisphere are named after figures from Greek mythology. One example is the story of Artemis, the goddess of the hunt, who slayed Orion. After feeling remorse, she placed him among the stars, giving rise to the equatorial constellation Orion. At the feet of Orion lies the constellation of the Great Dog, believed to be the loyal companion that followed its master into the heavens. Each star cluster in the Southern Hemisphere represents the shape of a creature or object, which is then named in their honor. Notable examples include Taurus, Virgo, Libra, and Scorpio.

In Perth, Australia, there is a sundial that exhibits characteristics commonly found in the Southern Hemisphere. At noon, the shadow falls in the south, while the Sun is positioned in the north. Additionally, the Sun’s apparent trajectory across the sky moves from right to left, resulting in the sundial’s numbering being counterclockwise.

The most brilliant star is the Full Moon in the Southern Hemisphere, specifically in Punta del Este.

1. The largest and oldest of all the oceans is the Pacific Ocean, with an area of 178.6 million cm2. It is often referred to as the Great Ocean because it can easily contain all the continents and islands combined. It is situated between the continents of Eurasia and Australia to the west, North and South America to the east, and Antarctica to the south.

2. The Pacific Ocean was explored and developed long before written records existed. Various types of vessels, such as junk boats, catamarans, and simple rafts, were used to navigate its vast expanse. In 1947, the Norwegian Thor Heyerdahl led an expedition on a log raft called the “Kon-Tiki,” which proved that it was possible to cross the Pacific Ocean from central South America to the islands of Polynesia. Chinese junks also sailed along the shores of the ocean, reaching the Indian Ocean.

3. The Pacific Ocean covers vast areas in all climatic zones, except for the polar regions. It experiences the formation of several areas of high and low pressure, resulting in the creation of winds and monsoons in the northwest. Typhoons are also common in this ocean. The properties of its water masses are largely influenced by the climate. Surface water temperature ranges from -1°C in the north to +29°C near the equator. Precipitation exceeds evaporation over the ocean, leading to slightly lower salinity in its surface water compared to other oceans. The warm waters of the Pacific Ocean create a favorable environment for coral reefs, which thrive abundantly here and form the largest “backbone” created by organisms.

4. Unfortunately, human economic activities have resulted in severe pollution in certain areas of the Pacific Ocean, particularly off the coast of Japan and North America. The depletion of whale stocks, valuable fish species, and other animals has been a consequence of this pollution. Some of these species have lost their former commercial importance.

Polaris, the brightest star, holds many fascinating secrets. Discover 10 intriguing facts about this celestial wonder.

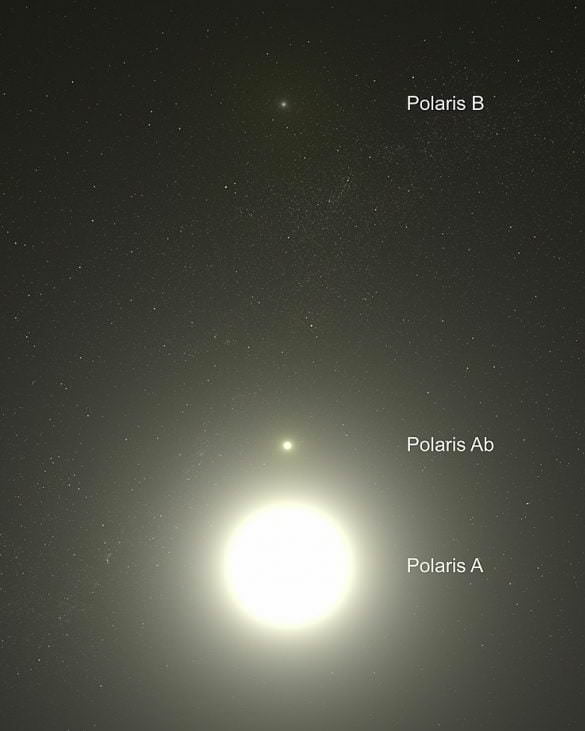

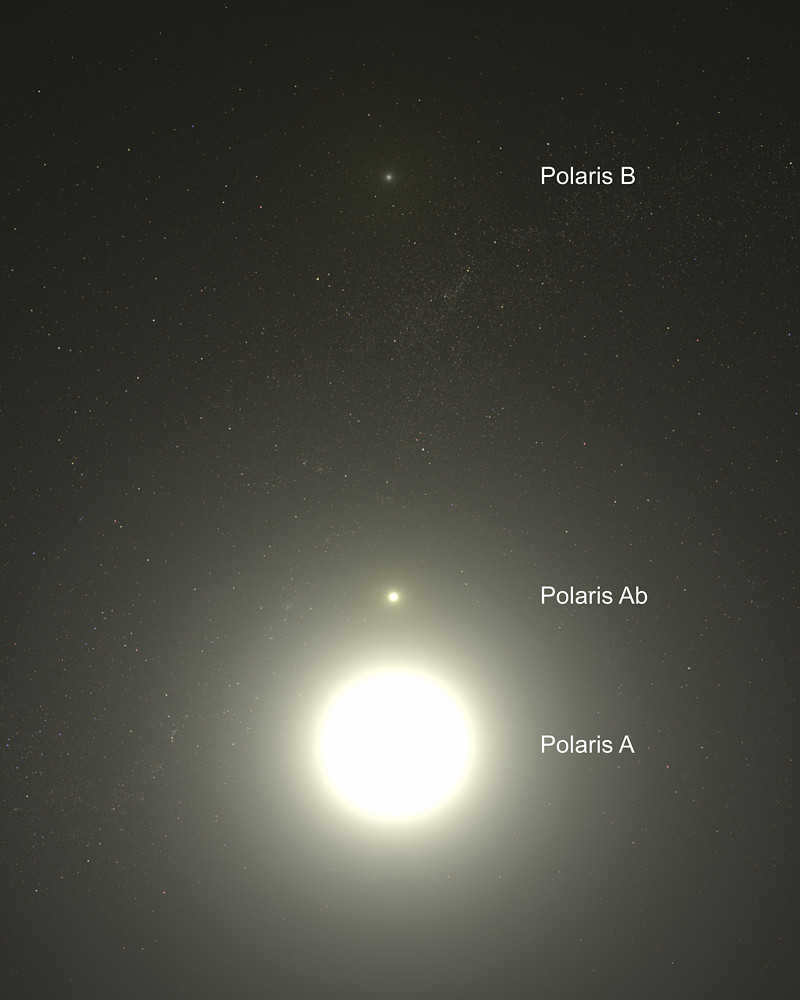

Polaris is composed of three stars, namely Polaris A, Polaris B, and Polaris Ab. Polaris A shines 2000 times brighter than the Sun.

Polaris does not hold the title of the brightest star in the sky. It occupies the 46th position on the list of the brightest stars in the Milky Way.

Being in close proximity to the North Pole has led to Polaris gaining popularity and recognition in the night sky.

Polaris has almost no apparent motion, making it a reliable landmark for travelers, sailors, and even tourists.

The star’s altitude above the horizon varies depending on the observer’s geographical location.

Polaris has been bestowed with various names, some of the most peculiar ones being Tethered Horse, Hole in the Sky, and even the North Nail.

This supergiant star boasts a radius that is 46 times larger than that of the Sun.

Locating Polaris is a breeze – just locate the constellation of the Little Dipper. It completes the handle of the “bucket” and aligns with two stars from the “bucket” of the Big Dipper.

Polaris pulsates! In 1999, its pulsation reached its minimum, and subsequently increased by a factor of 100.

There is a period when not one, but two polar stars or “guards” guard the Earth’s axis. They are equidistant from the North Pole and shine with equal brilliance.

Step #1: Locating the Big Dipper in the Night Sky to Locate Polaris

The most convenient way to locate Polaris is by using the handle of the Big Dipper or, as it is also known, the Big Bucket. This star configuration is likely known to anyone who has glanced at the night sky, so I won’t go into detail about it again, but rather explain how to find it in the evening sky.

The Big Dipper can be observed throughout the year, but its position in the sky varies depending on the season. The easiest time to locate this constellation is in the autumn and the first part of winter, when the handle is visible in the northern part of the sky, not too high above the horizon. During this time, the handle is horizontally positioned, making it easy to spot in the sky.

In autumn evenings, the Big Dipper can be easily found in the northern part of the sky. Image: Stellarium

In late winter, the handle abruptly moves up – resembling a handle – and ascends further into the sky. It also shifts towards the east. In spring, the dipper is almost directly overhead. This is why in late spring and early summer, it can be challenging for beginners to locate it – it is right above their heads!

In the second part of winter, the dipper stands upright in the northeast. Image: Stellarium

Finally, in summer, the dipper gradually descends towards the horizon, tilting as if going down a hill. During this time, it is observed in the southwest and west.

The Big Bucket in the summer sky. Image: Stellarium

Where can you find Polaris in the sky? The position of this star in relation to the cardinal directions

October 22, 2021 at 2:22, admin Tags: astronomy, stars, cosmos, Popular Science, North Star, star constellations

The North Star guides, but its guidance is temporary.

It is likely the most well-liked star amongst humans. Additionally, its popularity began to rise in ancient times when the Sun was not recognized as a star. However, to be honest, its “star status” only emerged recently by historical standards and is rather short-lived.

It is believed to possess exceptional brightness, although it is not the brightest and is rather average in this aspect. Some individuals believe it is the closest star, but that is also incorrect. There is a notion that Polaris can be seen from every corner of the Earth and can be used to navigate in all the oceans and deserts across the globe. However, this is also untrue. The true reason for the significance of this celestial body is only known to those familiar with astronomy.

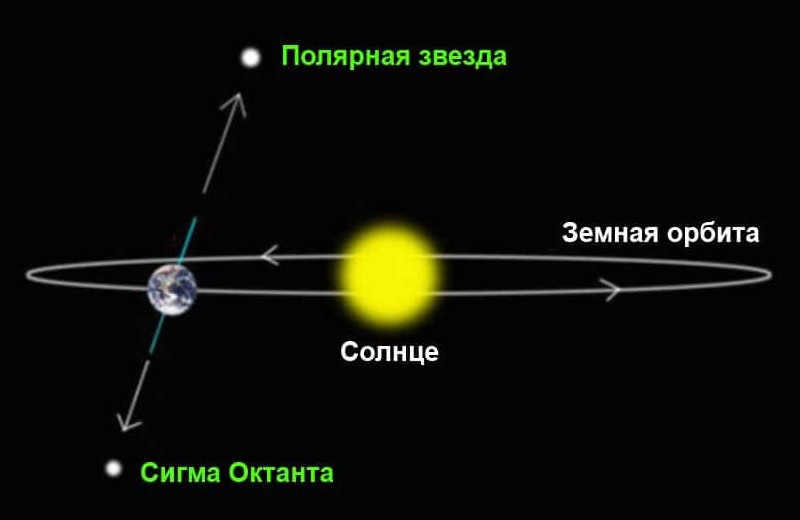

Firstly, Polaris is located on the celestial sphere at a considerable distance from the North Pole of the Earth – the point where the imaginary axis of rotation of our planet intersects with the imaginary sphere. However, the actual position of Polaris is very close to this point.

Doesn’t it seem like a lot of abstract thinking that requires a great deal of imagination?

It’s actually quite straightforward. If you extend the line connecting the Earth’s poles – the north and south – in a northern direction, that line will accurately point to Polaris.

By looking at this celestial body from any location in the northern hemisphere of the Earth, we will always be able to determine the direction in which the Earth’s axis of rotation is oriented.

Unfortunately, in the southern hemisphere of the planet, Polaris cannot be seen. It remains invisible throughout the year, both in winter and summer.

As a result, its usefulness for maritime navigation is limited in that region.

However, it is precisely its role in navigation that has contributed to the star’s popularity. After all, navigation originated in the northern hemisphere.

For ship captains and navigators, locating Polaris in the night sky was incredibly helpful. By dropping a plumb line from the star, they could determine the north and consequently navigate in any direction (east, south, west) while out at sea, where other reference points are scarce. The stars served as their only guide.

However, as time progresses, the stars undergo a shift in their position in relation to the horizon – they ascend, descend – and throughout the night, they traverse the entire expanse of the sky. It is impossible to navigate a ship based on a star that is constantly in motion, even if this motion is merely an illusion resulting from the Earth’s rotation.

And only the North Star, Polaris, consistently illuminates the point directly above the Earth’s northern axis.

By using special tables and making refraction corrections, it is possible to determine the latitude of the observation point with much greater accuracy using Polaris. Instead of rounding to the nearest degree, it is now possible to determine the latitude to the nearest one or two angular minutes, which corresponds to a distance of a few kilometers. This level of accuracy is sufficient for locating even very small islands.

Unfortunately, Polaris is not helpful in determining longitude. There are other methods available for this purpose. However, this article does not cover marine navigation techniques.

This is mainly a game and a matter of luck. For instance, there is no star of similar brightness in close proximity to the southern pole of the globe. Navigating in the oceans and seas of the southern hemisphere used to be slightly more challenging prior to the advent of GPS.

And even in the northern hemisphere, a few thousand years ago, people did not use Polaris for ship navigation. It did not even have that designation at that time.

Polaris Alpha of the Little Bear is a relatively recent name. It was not until the Renaissance that it began to be referred to as such, thanks to the Dutch cartographer Gemma Frizus. In 1547, he described it in one of his works as “stella illa quae polaris dicitur”, and the name stuck. Interestingly, during that time, Polaris Alpha was actually four times farther from the pole than it is today.

Prior to that, different peoples had different names for the alpha of the Little Bear. The Greeks called it “Kinosura”, which means “dog’s tail”. They did not see a bear around it, but rather a dog – the same dog that followed its mistress, the nymph Callisto. Callisto was turned into a bear by the jealous goddess Hera, but Zeus saved her and brought her to the heavens.

The ancient Celts referred to it as the “Ship-Star” – “Scip-steorra” – something they were already aware of regarding the future utilization of this celestial body.

Furthermore, the ancient Arabs, who bestowed names upon nearly all visible stars in the heavens, called Polaris “Al-Judei”, which translates simply as “Father”. Numerous Arabic star names are still utilized in the field of astronomy today. However, the ancient moniker of Polaris has been superseded and largely forgotten.

Regardless, in ancient times, from which all aforementioned astronyms of Polaris have been preserved, this guiding light was not employed for navigation, orienting in the landscape, or other related matters. It was far from the pole.

During the time of Archimedes and Pythagoras, the beta star of the Little Bear, known as “Kohab” or “Kohab-el-shemali” in Arabic, served as the “polar star,” which means “Star of the North.” Even earlier, during the era of pyramid construction, the closest star to the North Pole of the World was the alpha star of the Dragon, known as “Tuban.”

Back in those days, star charts did not include any mention of a Dragon.

As we now know, the North Pole of the Earth gradually moves across the star chart, transitioning from one star to another, completing a full circle every 26 thousand years. Currently, it is getting closer to Polaris and will reach its closest point in 2102, which is 80 years from now. At that time, the minimum distance between Polaris and the North Pole of the Earth will be 27 angular minutes, slightly smaller than the size of the moon. However, at present, the distance is almost a whole degree.

In the future, as time goes by, Polaris will no longer be known as the “Polaris” and will be replaced by Cepheus gamma in two thousand years. And another 10,000 years after that, the “polar” star for those living in the northern hemisphere will be the stunningly beautiful Vega, which is the alpha star of the Lyra constellation.

What other fascinating facts can be shared about Polaris?

Polaris, as previously mentioned, leads a small constellation known as the Little Bear, where it holds the position of the alpha star and shines the brightest. It is worth noting that the beta star of the Little Bear, called Kohab, is only slightly dimmer than Polaris, with a difference of just a few hundredths in star magnitude, making them indistinguishable to the naked eye.

Polaris is often found alongside the stars in the Big Dipper, and its brightness can be likened to theirs. By extending the line formed by the outermost stars of the Big Dipper five times, we will come across a moderately bright star – of the 2nd magnitude – and that star is none other than Polaris.

In the night sky, the polar star may not catch the attention of ordinary individuals due to its unremarkable appearance. However, scientists in the field of astronomy have discovered several distinctive characteristics and exceptional qualities of this celestial body.

Polaris is a multiple star. It can be challenging, but still possible, to observe a faint companion star, Polaris B, with an amateur telescope. However, the closer component of this system, Polaris Ab, can only be observed using the Hubble telescope or a similar instrument. Additionally, there are two more stars floating in the same direction at a distance from this “trio.” The status of these stars in relation to Polaris is still unknown, as astronomers are unsure whether they are part of a stable system or a scattered mini-cluster that will eventually disperse.

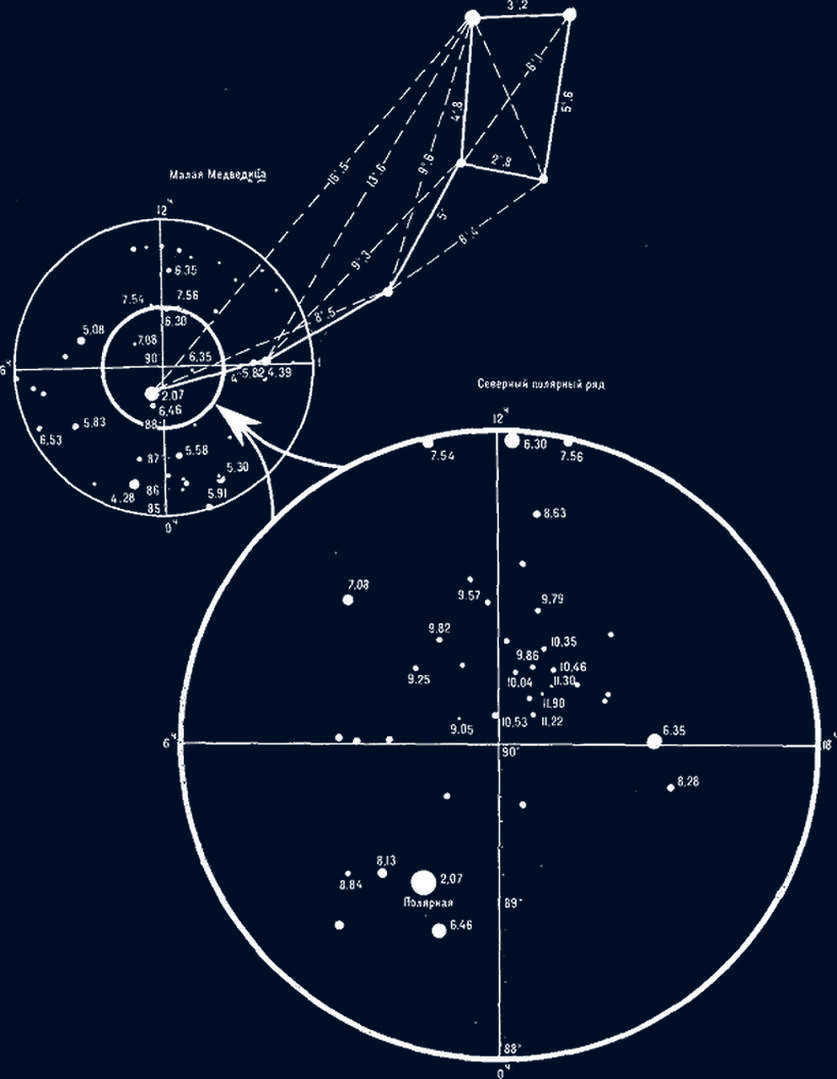

Astronomers have discovered several stars near Polaris that have a consistent brightness known as the Northern Polar Series. These stars are used as a standard for measuring the light of other stars because their constant position above the horizon ensures that the amount of light absorbed by the atmosphere remains the same, assuming clear and transparent skies.

At one point, Polaris itself was part of this group of stable stars and served as a reference for measuring celestial brightness.

It is now understood that Polar exhibits pulsations that cause its brightness to change in the same manner as most Cepheids, which are a type of variable star similar to Cepheus delta. However, Polaris possesses a unique characteristic that sets it apart as a Cepheid. Firstly, the amplitude of the variations in Polaris’ light is extremely small, just a hundredth of a star’s magnitude. This is why it was initially considered to be stable before the advent of accurate photometers. Additionally, over the course of its study, the amplitude of change in Polaris’ brightness has decreased by a factor of four, while the overall brightness of the star has increased. In the last century alone, Polaris has become 0.2m brighter, which is a significant change in the field of astronomy.

The outcome of the ongoing evolution of Polaris, which is occurring right before our eyes, remains unknown.

The distance to Polaris is vast. According to different estimations, it ranges from 300 to 500 light years (the latest data suggests 447 light years, and this distance is decreasing). The significant variation is attributed to the impossibility of accurately measuring the distance using the parallax method for such distant stars. Nevertheless, Polaris is still much farther away than the stars in the Big Dipper, which appear to have the same brightness. This implies that the actual luminosity of Polaris is much greater than that of the stars in the dipper.