The impact of Claudius Ptolemy on the field of science cannot be overstated. His contributions to astronomy, physics, mathematics, geography, and even music have not only been influential but have also served as a catalyst for the advancement of these disciplines. While much literature exists on Ptolemy’s achievements, there is a notable absence of biographical information.

Ptolemy authored the most comprehensive compendium on ancient astronomy known as the “Almagest”. This seminal work by the ancient scholar served as the “astronomy bible” until the advent of the Copernican theory, which revolutionized the study of celestial bodies.

Ptolemy’s wide range of scientific interests and profound analysis made him the pioneer of scientific literature in the fields of geography, physics (specifically optics), and music theory, among others. Additionally, Claudius formulated the theory that celestial bodies are in constant motion and operate as a single mechanism.

Ptolemy also contributed to the development of astrology, the study of the stars and their influence on human destiny. Furthermore, he created an astronomical atlas that depicted the constellations visible from Egypt.

Childhood and youth

There is no surviving information about the biography of the ancient scientist. This is because Ptolemy was deliberately not mentioned by his contemporaries in their writings. All the available information comes from the books of the scientist-physicist Philip Ball, as well as from Ptolemy’s own scientific works. It is known that Claudius lived in the city of Alexandria, which is now located in modern-day Egypt. Unfortunately, there are no remaining records about the appearance of the scientist, and any photos that exist today are based on an average image created by ancient sculptors.

Ptolemy, in his book “Almagest,” mentions the periods of astronomical observations, which can indirectly help determine the timeline of the scientist’s life: 127-151 years. However, even after completing the Almagest, Ptolemy went on to publish at least two more books, which were encyclopedias. The work on these books lasted another 10 years. According to the philosopher Olympiodorus, Ptolemy worked in the city of Canopus, a suburb of Alexandria Aboukir, near Alexandria.

Although Ptolemy’s name suggests an Egyptian origin, and his biographical data indicates Greek heritage, his first name, Claudius, points to Roman roots. Due to the lack of reliable information, it is not possible to definitively establish the scientist’s nationality.

Science and discoveries

Ptolemy embarked on his scientific journey with the creation of the “Kanopa Inscription”, an astronomical record etched onto a stone stele in the city of Kanopa, near Alexandria in Egypt. Although the stele itself has been destroyed over time, the valuable information it contained has been preserved through ancient Greek manuscripts.

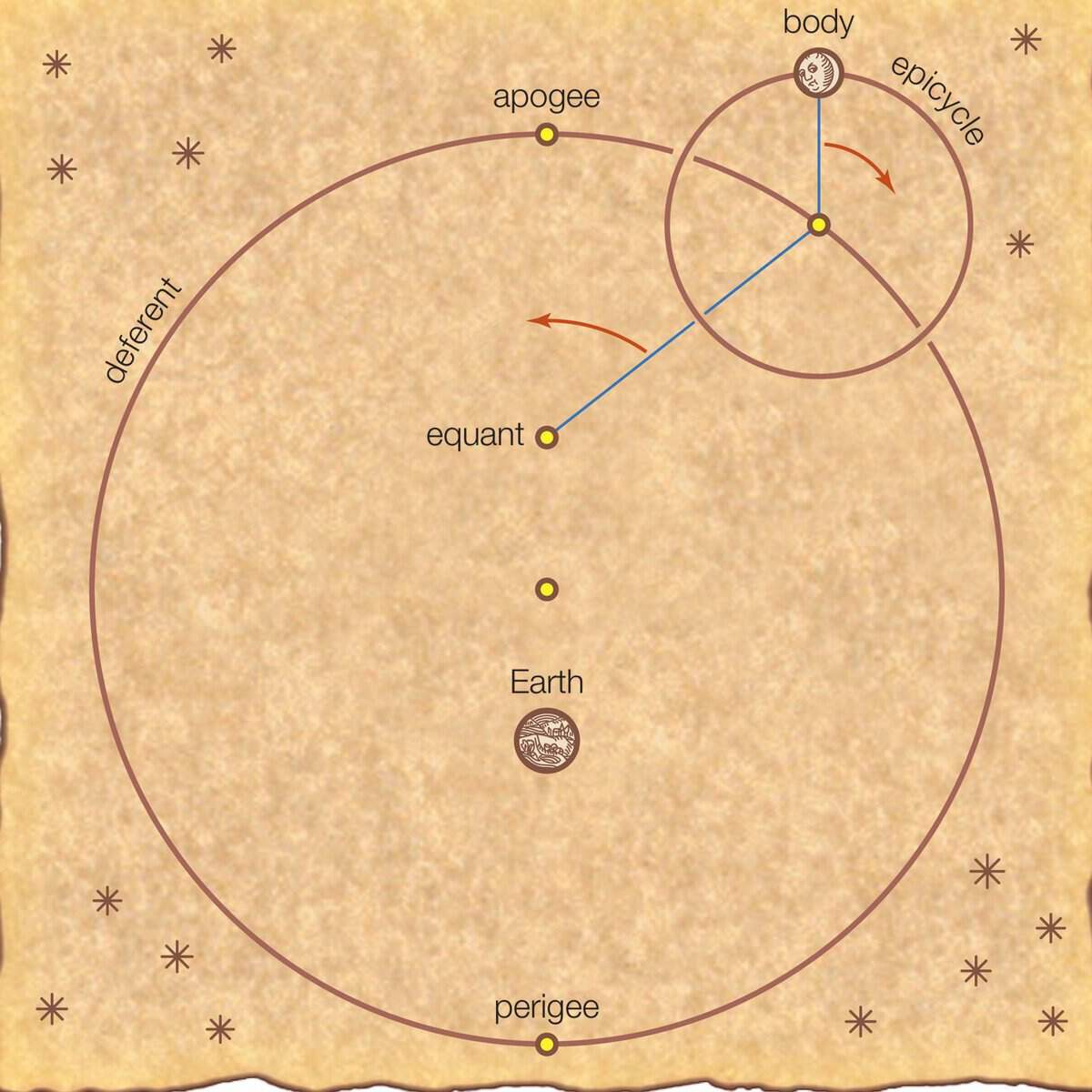

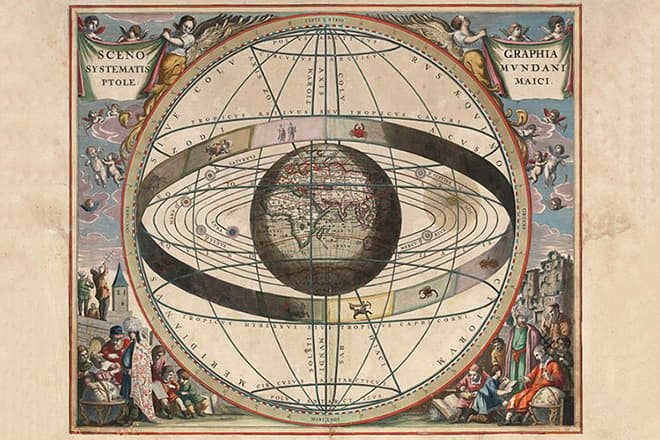

After meticulously analyzing the available data, Claudius proceeded to produce the “Handy Tables”, an indispensable astronomical manual. Within the framework of the geocentric theory, these tables provided evidence for the Earth’s fixed position and the orbiting motion of other celestial bodies around it.

Ptolemy, the renowned mathematician, was not only known for his groundbreaking work on the “Almagest,” but also for his contributions to other scientific books, including the “Planetary Hypotheses.” What sets this particular work apart from others is its utilization of a unique set of parameters to describe the positioning of astronomical objects. In this treatise, Ptolemy incorporates Aristotle’s concept of the “ether,” seamlessly integrating it into his theory.

In the Almagest, Ptolemy made extremely precise calculations of the distance between the Earth, Sun, and Moon, utilizing the Earth’s radius as the unit of measurement. However, in the “Planetary Hypotheses” section of the same work, Ptolemy provided distances between the Sun and other planets without reference to their radii. Instead, he used a logical deduction: the radius of a planet must be at least equal to its distance from the nearest visible celestial object. This discrepancy in methodology suggests potential variations in the time periods during which Ptolemy wrote his scientific papers.

According to researchers, the next book is titled “Phases of fixed stars”. This book marks the initial efforts to produce meteorological weather forecasts based on the positioning of celestial bodies and physical phenomena on Earth’s surface. Additionally, this work incorporates knowledge of climatic and geographical zones, as well as the relative placement of geographical objects, into a unified system.

In order to formulate astronomical theories, Ptolemy required geometric understanding of our planet. Claudius’ work, Analemma, covers the theorem for calculating radii, arcs, and circles. This knowledge has practical significance in the construction of sundials, which were created well before Ptolemy’s studies. Another work, “Planispherium,” explores stereographic projection and its application in astronomical calculations.

The work known as “Quadripartitum” by Claudius is highly enigmatic, as it explores the fundamentals of astrology and the impact of celestial bodies on human existence. On the other hand, the eight-volume “Geography” is just as renowned as the “Almagest.” It goes beyond being a mere descriptive geography and delves into the realm of mathematical geography, covering the fundamentals of cartography. In the first volume, the esteemed scientist proposed establishing the prime meridian based on the Canary Islands as the reference point.

The ongoing controversy and debate surrounding Ptolemy’s scientific contributions still persist today, as it is widely known that Hipparchus had already documented the positions of celestial bodies in the sky well before Claudius. The poet Omar Khayyam was the first to uncover the manipulation of data, and the arrival of Copernicus onto the global scientific stage rendered Ptolemy’s astronomical doctrine obsolete. Only Giordano Bruno briefly upheld the theory of geocentrism, aligning himself with the ancient scientist’s beliefs. However, it wasn’t long before other scientists discredited the geocentric model of the universe.

Personal life

There is no reliable information available about Claudius’s marital status or whether he had children. However, it is known that he had followers and assistants who played a crucial role in his scientific discoveries. Claudius dedicated his astronomical book “Almagest” to a person named Cyrus, but it is unclear who Cyrus was to the scientist and whether he had any involvement in his research or astronomy in general.

The same book mentions a mathematician named Theon, whose data Claudius used for his astronomical calculations. However, it is also unknown whether Theon was Ptolemy’s teacher or a colleague.

Some scholars believe that the individual in question is Theon of Smyrna, a philosopher and follower of Plato who also delved into the study of the celestial bodies and created a rudimentary map of the night sky.

Claudius had certain personal connections with the staff of the scientific library in Alexandria, Egypt, which allowed him unrestricted access to the necessary literature. While historical sources from the beginning of our era associate Claudius with the Egyptian Ptolemaic dynasty, modern researchers are inclined to view this as a mere coincidence.

The exact circumstances and date of the scientist’s demise, as well as all the details of his life story, continue to be shrouded in mystery. The prevailing consensus among the majority of scholars is that the year 165 AD should be regarded as the most likely time of Claudius’ passing.

Based on historical records, there was a widespread epidemic of the plague in Africa and Eurasia during this time, which Ptolemy may have succumbed to. However, even three millennia after his passing, the scholar’s legacy lives on in his works and continues to benefit future generations.

Bibliography

- “The Canopian Inscription”

- “Handy Tables”

- “Planetary Hypotheses”

- “Phases of fixed stars”

- “Analemma.”

- “Planispherium.”

- “Quaternary.”

- “Geography”

- “Optics.”

- “Harmonics.”

- “On the power of judgment and decision”

- “Fetus.”

- “Gravities” and “Elements.”

The Hellenistic period commenced following the conflicts led by Alexander the Great. Following the disintegration of his empire, Egypt, governed by the Ptolemies, emerged as one of the pivotal nations within the Mediterranean region.

General Ptolemy

Ptolemy, the future ruler of Egypt, was born in Eordea, a region in Upper Macedonia known for its mountainous terrain. His parents were Lagus and Arsinoe. Little is known about Ptolemy’s father, while his mother is believed to have been a member of the Argeades family.

Following the death of Alexander the Great, Ptolemy spread a rumor that his true father was King Philip. Supposedly, Arsinoe had already given birth to Philip’s child when she was married off to Lagus. There is also a tale that Lagus wanted to kill the child, who was not his own, but the infant Ptolemy was saved by an eagle.

Ptolemy was raised in the royal court in Pella alongside prince Alexander and other young noblemen. It is likely that he attended Aristotle’s lectures. In 336 BC, Ptolemy and some of Alexander’s friends were involved in the Pixodarus incident. As a result, Ptolemy, along with other friends of the prince, was exiled and later returned to his homeland after Philip’s assassination.

During the Persian campaign, Lagus’ son fought as part of the Getaires. In 331 BC, Ptolemy was given his first command when Alexander’s army was advancing towards the Persian Gate. With a force of three thousand soldiers, Ptolemy took the path that Ariobarzan was expected to retreat on.

In 328 B.C., according to the account of Arrian, it is said that Ptolemy led one of the divisions of the Macedonian army during the reconquest of Sogdiana. However, other sources mention only three divisions and do not list Ptolemy as one of the commanders. It is possible that Ptolemy may have exaggerated his role in the campaign as he grew older.

Ptolemy, the son of Lagus, was also present at the significant banquet in Maracanda, where Alexander killed his companion Clytus. Ptolemy even tried to calm the commander of the Getaires and prevent the argument, but his efforts were unsuccessful.

A year later, Ptolemy played a part in exposing a conspiracy among the king’s followers. One of the conspirators approached Ptolemy and decided to betray his accomplices. Ptolemy informed the king about what had transpired.

Laga’s son displayed great courage in the battles fought in India. In the conflicts against the Aspasiev tribes, Ptolemy engaged in a duel and successfully defeated one of their leaders. He then assumed command of a separate contingent and played a crucial role in expelling the Indians from their hill positions.

During the battle at Hydaspes, Lagus’ son fought alongside Alexander’s forces, crossing the river and launching a flank attack on Porus. Furthermore, Ptolemy demonstrated his strategic prowess during the siege of Sangala, where he positioned himself to counter the Indian attempts to break out of the city. His leadership successfully repelled their assault. Later in the campaign, he once again commanded a significant portion of the Macedonian army, effectively subduing numerous Indian settlements.

Upon their return from India, Ptolemy accompanied Alexander through the challenging desert terrain of Gedrosia. This treacherous journey resulted in the loss of many lives.

In Susa, during the renowned wedding ceremony following the march to India, Ptolemy was bestowed with a Persian spouse. The bride, Artakama, was the daughter of the satrap Artabaz and the sister of Alexander’s paramour, Barsina. As a token of appreciation, the king gifted Ptolemy and his fellow guards with opulent golden wreaths. Artakama’s presence in the life of the Egyptian monarch remains relatively obscure, as she did not play an active role unlike the other women.

Wars of the Diadochi

Following the death of Alexander in 323 BC, Ptolemy was appointed as the satrap of Egypt. He took over the position from the previous satrap, Cleomenes, who then became his deputy-hipparch. However, Ptolemy eventually had to execute Cleomenes due to his unreliability. Ptolemy’s influence is evident in the negative portrayal of Cleomenes in ancient historical accounts. Despite this, Cleomenes, who was originally appointed by Alexander, proved to be an effective governor and managed to accumulate 8,000 talents in the treasury, which later passed on to Ptolemy.

In the neighboring region of Cyrene, there was civil unrest, and the exiled aristocratic rulers sought help from Ptolemy. In 322 BC, Ptolemy dispatched an army under the command of his general, Ofellus, to assist them. Ofellus successfully subdued the cities of Cyrenaica and assumed the role of their governor.

Unrest was growing in the conquered land, prompting Ptolemy to travel to Cyrenaica himself. It was there that he introduced the Diagram of Cyrenaica, outlining the principles that would govern the subjugated polis in his domain. The aristocracy regained their authority in Cyrenaica, while Ptolemy held supreme power as both strategist and chief judge. Thus, Cyrene, which had been granted the status of a free polis by Alexander, became a part of the empire.

In the heart of Alexander’s dominion, turmoil was brewing as Craterus, Antipater, and Lysimachus grew discontent with the rule of regent Perdiccas. Ptolemy aligned himself with them, and part of their conflict centered around the custody of the deceased king’s body. Perdiccas had ordered the body to be sent to Aegae, the ancestral tomb of the Argeadic kings of Macedonia.

The train transporting the king’s sarcophagus had to travel all the way from the Middle Ages to Macedonia. However, during the procession in Syria, Ptolemy’s soldiers intercepted it and convinced the commander Arridaeus to bring the king’s body to Egypt. Initially, Alexander was laid to rest in Memphis, but a new tomb was later constructed for him in Alexandria.

Alexander was highly revered as the protector of the Ptolemaic state. In Alexandria, a cult dedicated to the deceased king was established, and its priests were aristocrats from Macedonian families.

Ptolemy’s actions led to the start of the war, and it was Egypt that Perdiccas launched the initial attack on. In 320 BC, former generals of Alexander gathered for a battle on the Nile River. Initially, Ptolemy successfully defended the Camel Fortress against Perdiccas’ assault. Then, the regent attempted to cross the Nile but was defeated, resulting in many soldiers drowning or falling prey to crocodiles.

A conspiracy formed against Perdiccas, involving generals Python, Seleucus, and Antigenes, the commander of the Argyraspidae. Perdiccas died, and a few days later news arrived of his ally Eumenes’ victory over Craterus. Ptolemy showed mercy towards the prisoners and provided provisions for the defeated army. When offered the vacant position of regent, Ptolemy declined.

Shortly after these events, the generals of Alexander gathered in the city of Triparadis. It was there that they selected a fresh regent and reorganized the satrapies. The generals officially recognized Ptolemy as the satrap of Syria and also gave their approval for the incorporation of Cyrene. They also authorized the satrap to continue his campaigns in the western regions.

Upon the death of the regent Antipater in 318 BC, as a new conflict among the Diadochi was on the horizon, Ptolemy took control of Syria and Phoenicia. The satrap made it a point to show his unwavering loyalty to the king. In 316 BC, Alexander IV was acknowledged as the Egyptian pharaoh, with cartouches bearing his name engraved on various artifacts.

In 315 BC, after being exiled by Antigonus, Seleucus, the satrap of Babylon, sought refuge in Egypt where he was warmly welcomed by Ptolemy. Little did anyone know that their alliance would lead to years of struggle against the successors of Seleucus.

This marked the beginning of the third war of the Diadochos, with Seleucus, Ptolemy, and Cassander joining forces against the formidable Antigonus. Antigonus managed to expel Ptolemy’s garrison from Tyre and declared the freedom of the Greek cities from there. In response, Ptolemy issued his own proclamation, asserting the freedom of the Greeks (a tactic employed by other rulers during that time as well).

After losing his satrapy, Seleucus became an active aide to the ruler of Egypt. Initially, he and Ptolemy’s brother Menelaus successfully conquered Cyprus. As a result, Nikokreon, the governor of Cypriot Salamina, became the island’s strategist.

Meanwhile, in the western region, Ptolemy expanded his satrapy’s borders to include Greater Sirte and gained control over the caravan routes from Central Africa. In 313 BC, there was a rebellion in Cyrene, but the satrap’s army and navy were able to suppress it, and Ofellus remained as the governor of the region.

In 312 BC, Ptolemy and Seleucus defeated Demetrius, who was the son of Antigonus, at Gaza. However, a year later, Demetrius got his revenge by defeating Ptolemy’s general, Killus. In the face of Antigonus’ main forces, the satrap of Egypt chose to retreat and cede Syria to his opponent.

In 311 BC, Seleucus successfully captured Babylon with a small detachment and held off Antigonus’ troops during the siege. This event marked the beginning of the Seleucid “royal era”. The Diadochi once again made peace in the same year, but this only set the stage for future conflicts, as Ptolemy’s conquest of Cyprus was not officially recognized.

Shortly after the peace agreement, Cassander ordered the murder of Roxana and King Alexander, plunging the empire into a period of interregnum. In Egypt, they continued to mark the passing years as if Alexander was still alive and ruling.

Even though the peace treaty of 311 B.C. officially declared the Greek cities as independent, the Diadochi were not enthusiastic about enforcing this decision in their territories. As a result, Ptolemy found a justification to launch an assault on Cilicia, which was under the control of Antigonus and housed Greek polis. However, Antigonus’ son Demetrius successfully defended against the attack.

In 310 BC, Nicocreontes, who was an ally of Ptolemy, passed away. Menelaus, Ptolemy’s sibling, inherited the position of strategist of Cyprus and became the king of Salamina. After this event, the satrap of Egypt continued the war of “liberation” in the southern region of Asia Minor. He managed to conquer and gain the support of several Greek city-states in that area. However, at Halicranassus, Demetrius once again halted Ptolemy’s progress. The significance of the war in Asia Minor can be seen from the fact that Ptolemy himself was leading the campaign. His headquarters were located on the island of Kos, where his wife and future son, Ptolemy II, remained.

The climax of the conflict in Asia Minor and Cyprus came in the form of a naval battle. In the vicinity of Salamina, Demetrius emerged victorious against Ptolemy’s fleet. As a result, Demetrius controlled the island for a period of 12 years.

King Ptolemy I

Following the impressive achievements of his son, Antigonus declared himself king, asserting his claim as the new heir of Alexander. In a similar fashion, Ptolemy also assumed the royal title. Consistent with Macedonian tradition, Ptolemy was proclaimed king by his army. This pattern was followed by the other Diadochi – Lysimachus, Seleucus, and Cassander. The year 306 B.C. is remembered as the “Year of the Kings,” during which Alexander’s generals effectively dismantled his empire.

Antigonus and Demetrius launched a joint military campaign against Egypt, with Antigonus leading the land offensive and Demetrius attacking from the sea. However, Antigonus’ forces faced major obstacles in the form of the swamps in the Nile Delta, causing their advance to fail. Meanwhile, Ptolemy successfully repelled the landing of Demetrius’ troops, forcing Antigonus and his son to retreat.

In the aftermath of the failed invasion, Ptolemy was officially crowned as the ruler of Egypt on the regular anniversary of Alexander’s death, which occurred around January 304 BC. This coronation was recognized by the island polis of Rhodes, further solidifying Ptolemy’s title.

A year later, Demetrius made another attempt to conquer Rhodes, earning himself the nickname Poliorketes, meaning “besieger of cities.” The siege was long and difficult, but Rhodes managed to withstand the attack. Ptolemy, showing support for Rhodes, sent food supplies and additional troops to reinforce the island’s garrison.

In recognition of their victory, the people of Rhodes erected the iconic Colossus statue and bestowed honors upon Ptolemy, the king of Egypt.

In 301 BC, the forces of Antigonus and Demetrius suffered a crushing defeat, leading to the collapse of Antigonus’ empire. Antigonus himself perished in the battle. His son, however, managed to hold onto his territories in the islands and Greece, along with a formidable fleet. Interestingly, Ptolemy’s troops were not directly involved in the conflict at Ipsus. Instead, while his fellow kings battled Antigonus in Asia Minor, Ptolemy seized control of Syria up to the city of Byblos. It is worth noting that Sidon and Tyre remained under the control of Demetrius.

As per the agreement among the conquerors, Seleucus was granted control over the entire region of Syria. The ruler of Babylon chose not to assert his claim over Ptolemy’s possessions, but he also did not relinquish them. This set the stage for the Syrian wars, where the descendants of Ptolemy and Seleucus would clash. Syria and Phoenicia were prosperous territories where caravans from Arabia would conclude their journeys.

Through a peace treaty between Ptolemy and Demetrius, the prince of Epirus, Pyrrhus, who resided in Demetrius’ court, became a hostage in Alexandria. Ptolemy and Pyrrhus developed a friendship, and the Egyptian king aided Pyrrhus in reclaiming his throne in Epirus. In Egypt, Ptolemy arranged the marriage of his stepdaughter, Antigone, to Pyrrhus. Later on, Pyrrhus even named one of the cities he founded after his mother-in-law, Berenice.

The conflicts among the generals of Alexander the Great persisted. In 294 BC, Demetrius took control of the Macedonian throne. The other rulers launched assaults on his scattered territories throughout the Mediterranean. Ptolemy successfully conquered Cyprus, Sidon, and Tyre.

Ptolemy’s naval forces supported Athens’ rebellion against Demetrius. Envoys from the Egyptian king played a role in negotiating a peace agreement that allowed Athens to remain independent but resulted in the loss of Piraeus. In the Mediterranean region, Ptolemy was able to gain control over the Union of Islanders established by Antigonus. As a result, the Ptolemies held power over the Cyclades islands until the mid-3rd century BC. In the subsequent years, Ptolemy regularly provided financial and food assistance to Athens, upon which the city relied.

Ptolemy’s Female Companions

Throughout the reign of the Egyptian king, Ptolemy, there were numerous women who played significant roles in his life. One such woman was Artakamas, a Persian lady, who seems to vanish from historical records following their wedding in Susa.

As the struggle for power intensified, the satrap of Egypt, Ptolemy, entered into a union with Eurydice, the daughter of regent Antipater. Together, they had two children: Ptolemy, known as Keravn or “Lightning,” and Meleager. Although they were not destined to inherit their father’s throne, they eventually had their own brief stints as rulers in Macedonia.

Berenice, a Macedonian woman, arrived in Egypt as part of Eurydice’s retinue. She was widowed, and her son Magus was given a prominent position in his stepfather’s state. Initially, Berenice was Ptolemy’s mistress before becoming his wife. She gave birth to a daughter named Arsinoe and a son named Ptolemy, who would later become the king. Arsinoe eventually married Lysimachus, the aging king of Thrace and a comrade-in-arms of her father during Alexander’s campaign and the fight against Antigonus. In turn, Ptolemy’s son married Lysimachus’ daughter, who is commonly known as Arsinoe I to avoid confusion. After her husband’s death and the downfall of his kingdom, Ptolemy’s daughter returned home and later married her brother. She is famously known as Arsinoe II in the history of the dynasty. The well-known Gonzaga Cameo is believed to depict Ptolemy II and Arsinoe II.

Afterwards, she became the partner of Ptolemy. According to the author Athenaeus, she initially served as his mistress and later became his wife. Thais gave birth to three children with Ptolemy, but their significance in history was minimal. The oldest son, named Lagus after Ptolemy’s father, is only known for winning a chariot race in Arcadia in 308 BC.

Around 287 BC, Eurydice and her sons departed from Egypt. They resided at the courts of Seleucus and Lysimachus. Ptolemy II became his father’s co-emperor during the final years of his reign.

Towards the end of his life, Ptolemy authored a work about Alexander’s campaign. Although the text has been lost, Arrian, who lived in the 2nd century AD, wrote a book based on it titled Alexander’s Campaign.

King Ptolemy of Egypt peacefully passed away in 283 B.C., leaving his son Ptolemy II to inherit the throne, who proved to be a worthy successor. Two years prior, Demetrius, after another daring adventure, was captured by Seleucus and met the same fate as Ptolemy in that same year. Seleucus outlived his counterpart by two years. He emerged victorious against and killed Lysimachus, and was on the brink of seizing Macedonia, but was ultimately slain by Ptolemy’s illegitimate son, Keravn.

Simultaneously with Ptolemy, all those who had once captured Alexander the Great had also passed away. Ptolemy II ruled in Egypt, while Seleucus’ son, Antiochus I, reigned in the east. In Greece, Demetrius’ son, Antigonus, was preparing to regain control over Macedonia. The dawn of a new era was illuminating the Mediterranean.

- Elis W.M. Ptolemy of Egypt. 1994

- Heckel W. Alexander’s Marshals. An examination of the aristocracy of Macedonia and the dynamics of military leadership. 2016

- Holbl G. A Chronicle of the Ptolemaic Empire. 2010

Today, we will discuss the remarkable achievements of Claudius Ptolemy, an individual who made significant contributions to the field of science. Ptolemy, a Greek astronomer, mathematician, and geographer, remains an influential figure despite the scarcity of information about his personal life. While the details of his birthplace and date remain unknown, as well as the location of his passing, his profound impact endures.

Consequently, this article aims to provide a comprehensive account of Claudius Ptolemy’s biography and accomplishments.

Biography of Claudius Ptolemy

The exact birthplace of Claudius Ptolemy is unknown, but it is believed to be in Egypt. All of his documented activities occurred between the year 127 AD, when he made his first recorded observation. This observation took place during the eleventh year of Emperor Hadrian’s reign. Conversely, one of his later observations is dated 141 AD. In his star catalog, he used the first year of Emperor Antoninus Pius’ reign as the reference date for all coordinates. This starting year was 138 AD.

The admiration that all of Claudius Ptolemy’s works inspired introduced the tradition of referring to him as the megiste, which is the Greek term for both great and maximal. The work was so impressive that in 827, the Caliph al-Ma’mun translated the entire Arabic version. According to the translation, the name al-Maghisti is derived from Almagest. This name was later adopted in the medieval West after the first Arabic translation was made in Toledo in 1175.

Distinctive Features of Claudius Ptolemy’s Work

Claudius Ptolemy utilized the data gathered by his predecessors to construct a comprehensive model of the world system. This model accurately represented the apparent movements of the Sun, Moon, and the five known planets at that time. Ptolemy particularly relied on the data collected by Hipparchus, as it provided crucial insights. By employing geometric capabilities and complex calculations, he managed to establish these mechanisms with a certain degree of precision. This understanding was based on the geocentric system. According to this system, the Earth, positioned at the center of the universe, remains motionless. All celestial objects, including the sun, moon, and other planets, orbit around our planet.

During that period, the planets that were identified included Mercury, Venus, Jupiter, and Saturn. In this particular system, the Earth occupied a slightly off-center position in relation to the central point of all the orbits on which the other celestial bodies moved. These paths of movement were referred to as distinct orbits. The only heavenly body that traversed its orbit evenly was the Sun. On the contrary, the Moon and the remaining planets moved along a separate orbit. This particular orbit was known as an epicycle. The center of the epicycle would rotate in relation to the deflector. This feature allowed him to elucidate all the irregularities that were observable in the movements of the celestial bodies to Claudius Ptolemy.

This system had the capability to offer an explanation for the movements of the planets that aligned quite well with the principles of Aristotelian cosmology that were prevalent during that era. It also remained the sole model until the Renaissance. In the Renaissance, there was an improvement in the accuracy of celestial observations and a wealth of information became available through numerous astronomical studies. Most of the knowledge about astronomy during this time was obtained towards the end of the medieval period. With this newfound understanding, it became necessary to introduce numerous additional epicycles, further complicating the comprehension of anything related to astronomy.

Indeed, the heliocentric model introduced by Copernicus marked the beginning of the disappearance of all of Claudius Ptolemy’s astronomical theories due to its remarkable simplicity, which was considered one of its greatest strengths.

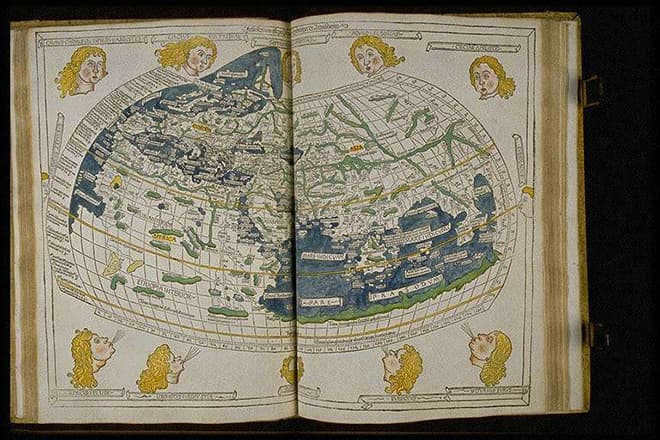

However, it is important to note that Claudius Ptolemy was not just an astronomer, but also a geographer. His expertise in geography allowed him to have a significant impact through important geographical discoveries. In his extensive 8-volume work called geography, he compiled mathematical methods for creating accurate maps using various projection systems. Additionally, he collected a vast array of essential geographic coordinates for different locations around the world, as known at that time.

In order to advance with this project, Claudius Ptolemy took into consideration Posidonius’ calculation of the Earth’s circumference. However, Posidonius’ estimation turned out to be smaller than the actual value, which resulted in an exaggerated measurement of the Eurasian continent from east to west. It was this discrepancy that motivated Christopher Columbus to set sail on his famous journey, ultimately leading to the discovery of America.

Additional Works

Claudio Ptolemy also produced another notable piece, referred to as “Optics”. This extensive work is divided into five volumes and primarily focuses on the theory of mirrors, as well as the phenomena of reflection and refraction of light. These physical phenomena were taken into consideration during astronomical observations. Additionally, Ptolemy is recognized for his contribution to astrology with his treatise entitled “Tetrabiblos”. This text encompasses various characterizations and other writings, and held significant importance during the Middle Ages.

By delving into these works, you can gain a deeper understanding of Claudio Ptolemy’s biography and accomplishments.

The accuracy of the content in this article aligns with our editorial ethics guidelines. If you spot any errors, please click here to report them.

Full article path: Network Meteorology “Meteorology” release by Claudio Ptolomeo

Claudius Ptolomeo (Ptolemy) (c. 90 – c. 160) was an ancient Greek scientist renowned for his mathematical theory on planetary motion around the stationary Earth. This groundbreaking theory enabled him to accurately calculate the positions of planets in the sky. Along with his theories on the Sun and the Moon’s motion, Ptolemy’s work formed the basis of the Ptolemaic system of the world.

Claudius Ptolemy, a Greek geometer, astronomer, and physicist, resided and conducted his work in Alexandria during the first half of the 2nd century BC. Despite his significance in the scientific community, ancient Greek literature does not provide much information about his personal life, worldly connections, or even his birthplace.

Claudius Ptolemy, just like his predecessors, including Hypsicles, divides the circumference into 360 equal parts, which are further divided into halves. The diameter is divided into 120 parts, which are then subdivided into 60th or first parts, and 3600th or second parts. These parts are translated into Latin as partes minutae primae and partes minutae secundae, and have become known as minutes and seconds in modern languages. The technique of dividing the circumference and diameter originated in Chaldea.

The third book focuses on the length of the year, with Cassini providing the nearest minute measurement. It also presents Hipparchus’ theory of the Sun.

The fourth book discusses the determination of the length of the month and presents the theory of the moon’s motion.

The fifth book focuses on the explanation of the astrolabe and also includes references to new measurements conducted using this instrument. These measurements were used by the author to conduct a more precise study of the irregularities in the Moon’s motion.

In the sixth book, Ptolemy explores the conjunctions and oppositions of the Sun and Moon, as well as the circumstances surrounding the occurrence of eclipses. The book also mentions the possibility of making an approximate calculation of when these events will happen.

Astronomy: Ptolemy’s Almagest is a highly significant work in ancient astronomy. It is noteworthy for its depiction of the geocentric model of the universe, which illustrates the motion of the Sun, Moon, and planets in relation to the Earth. The Almagest also includes a comprehensive catalog of stars, with their brightness measured on a logarithmic scale. The entire work was published in 13 volumes.

Geography: Ptolemy provided a comprehensive description of the world’s geography during his time in his renowned work titled Geography. Ptolemy’s maps spanned a vast area, covering 180 degrees of longitude from the Canary Islands to China, and 80 degrees of latitude from the Arctic to the East Indies;

Astrology: Ptolemy’s contribution to astrology is encapsulated in his treatise known as the Tetrobible. This influential book played a significant role in the practical advancement of astrology. Ptolemy dismissed methods lacking a logical basis and maintained that astrology could not be considered a wholly reliable science. His treatise consisted of four books.

If you found the content valuable and helpful, please feel free to share it with your friends!

Claudius Ptolemy, born around 100 AD and died around 170 AD, was a renowned Greek astronomer, mathematician, and mechanic. His immense contributions to various fields of science have left a lasting impact. Ptolemy’s extensive knowledge not only broadened the horizons of his contemporaries but also provided explanations for numerous natural phenomena. Additionally, he played a crucial role in improving the accuracy and comprehensibility of world maps during his time.

Childhood and youth

There is no surviving information about Ptolemy’s biography. However, we can gather information about the scientist’s life and activities from his own writings.

We know that Claudius resided in what is now Egypt, specifically in the city of Alexandria. The name Ptolemy suggests an Egyptian heritage, while the first name Claudius indicates the scientist’s Roman roots, even though he was originally from Greece.

Contribution to astronomy

Contribution to science

In ancient times, Ptolemy was a well-known figure. This multifaceted individual, a gifted scientist, was able to provide solutions to numerous inquiries, expand the boundaries of knowledge for his contemporaries, and lay the necessary groundwork for future research.

Claudius Ptolemy (100-170) was an Egyptian astronomer, geographer, mathematician, poet, and astrologer. He is renowned for his development of the geocentric model of the universe, commonly referred to as the Ptolemaic system. Additionally, he made efforts to establish latitude and longitude coordinates for significant locations on Earth, although his maps were later found to be inaccurate.

The outstanding achievement of Ptolemy was his ability to synthesize the vast body of Greek knowledge into the most comprehensive and representative work of ancient times. He can be considered the final and most significant scholar of the classical era.

Life Story

Claudius Ptolemy was born around 85 AD, although some sources suggest that he may have been born closer to 100 AD. This uncertainty arises from the lack of historical records about his early years.

It is believed that he was born in Upper Egypt, specifically in the city of Ptolemais Hermia, situated on the eastern bank of the Nile River.

Ptolemais Hermia was one of three Greek-founded cities in Upper Egypt, the other two being Alexandria and Naucratis.

There is limited biographical information about Ptolemy, but it is known that he spent his entire life working and residing in Egypt.

According to certain historical records, Ptolemy focused primarily on astronomy and astrology. In addition to these pursuits, he also gained recognition as a remarkable mathematician and geographer.

Approach

A distinctive aspect of Ptolemy’s methodology is his reliance on empiricism, a research approach that he applied across all of his works and that set him apart from his contemporaries.

Furthermore, many of Ptolemy’s descriptions were not meant to provide accurate and literal depictions of the phenomena he studied; rather, he aimed to comprehend and explain the reasons behind these phenomena based on his observations.

This incident occurred while attempting to elucidate the concept of epicycles, first introduced by Hipparchus of Nicaea and subsequently expanded upon by Ptolemy. Through this theory, he endeavored to depict the generation of the stars’ movements in a geometric manner.

The impact of Hipparchus

Hipparchus of Nicaea was a cartographer, mathematician, and astronomer who lived between 190 and 120 BC.

There is no direct information available about Hipparchus; the knowledge that has come to light has been derived from the Greek historian and cartographer Strabo and from Ptolemy himself.

Ptolemy frequently acknowledged the triumphs and accomplishments of Hipparchus, attributing various inventions to him. One such invention was a compact telescope, essential for enhancing the process of measuring angles, which could be employed to determine that the length of the solar year was approximately 365 days and 6 hours.

Moreover, Ptolemy’s reliance on Hipparchus can be seen in the initial publication he produced, known as Almagest. This significant work will be further discussed in the upcoming sections.

Ancient Alexandria’s Library

Throughout his lifetime, Ptolemy dedicated himself to observing the stars in the city of Alexandria during the reigns of Hadrian (117-138) and Antoninus Pius (138-171).

Claudius Ptolemy is recognized as a prominent figure from the second stage of the Alexandrian school, which occurred after the Roman Empire’s expansion.

Although there is no concrete evidence, it is speculated that Ptolemy carried out his research at the renowned Library of Alexandria. Working in this esteemed institution could have granted him access to the writings of earlier astronomers and mathematicians.

If this theory is accurate, it is believed that Ptolemy was the one who gathered and organized the knowledge of ancient scholars, specifically in the area of astronomy. He gave structure to a dataset that may have originated as far back as the 3rd century BC.

Additionally, it is understood that Ptolemy’s contributions in astronomy went beyond just organizing existing work. He also made significant advancements in understanding planetary motion.

While working at the Library of Alexandria, Ptolemy authored a book that would become his most iconic work and his greatest contribution.

This book, with a title of Arabic origin, corresponds to the initial version of the text to reach Western audiences.

Plain Language

An essential aspect of Claudius Ptolemy’s philosophy is his recognition of the importance of conveying his message clearly to all readers.

He understood that by doing so, knowledge could be accessible to a wider audience, regardless of their mathematical background. It was also a means of preserving that knowledge for future generations.

Therefore, Ptolemy wrote a simplified version of his planetary motion hypothesis, using language that was easier to understand and specifically tailored for individuals without mathematical training.

Potential Impact on Columbus

Ptolemy was a renowned geographer who made significant contributions to his field. He created a variety of maps that included important landmarks, and he used longitude and latitude coordinates to pinpoint specific locations.

While these maps were impressive for their time, they were not without flaws. Given the limited resources and technology available during that era, it is understandable that they contained some inaccuracies.

In fact, there is evidence suggesting that Christopher Columbus, the Spanish explorer, relied on one of Ptolemy’s maps during his voyages. It was this map that gave Columbus the notion that it might be possible to reach India by sailing westward.

Death

Claudius Ptolemy passed away in 165 AD in the city of Alexandria.

Contributions to science

Astronomy

His significant contribution to the field of astronomy is the Almagest, a book that drew inspiration from the research conducted by Hipparchus of Nicaea. Ptolemy’s work proposed that the Earth is the center of the universe and remains stationary, with the sun, moon, and stars revolving around it.

Based on this assumption, all celestial bodies are believed to move in perfectly circular orbits.

Ptolemy dared to project the measurements of various celestial bodies, including the Sun, Moon, and a total of 1,028 stars.

Astrology

In ancient times, people believed that the positioning of the Sun or Moon at the time of birth had an impact on individuals’ personalities.

Ptolemy created his renowned treatise on astrology, called Tetrabiblis (Four Books), which extensively discussed the principles of astrology and horoscopes.

According to his theories, the influence of the sun, moon, stars, and planets caused the ailments and diseases that people experienced.

Each celestial body had a specific effect on different parts of the human body.

Optics

In his work Optics, Ptolemy was a pioneer in the study of the law of refraction.

Geography

Another one of his most influential works is titled Geography, a work that he finished because Marino de Tiro was unable to complete it.

It is a compilation of mathematical techniques for producing accurate maps. It includes various projection systems and collections of coordinates for the major known locations around the world.

While Ptolemy’s maps served as a precedent for the creation of more precise maps, he did exaggerate the size of Asia and Europe.

There is no doubt that Ptolemy made significant contributions to geography, as he was one of the pioneers in creating maps with coordinates, longitude, and latitude. Despite their errors, his works set the stage for future advancements in cartography and earth sciences.

In the realm of music, Ptolemy authored a composition on the principles of music known as Harmonics. He posited that mathematics had a profound impact on both musical systems and celestial entities (Wikipedia, 2017).

Ptolemy held the belief that specific musical notes were directly derived from particular planets. He reached the conclusion that the distances between planets and their movements had the ability to alter the resonance of instruments and music as a whole.

The sundial

Biography of Claudius Ptolemy (90-168)

Claudius Ptolemy was a Greek astronomer and astrologer who made significant contributions to the fields of science, geography, and the understanding of the universe. He is most well-known for his work on the Almagest, a comprehensive guide to astronomy that laid the foundation for future discoveries. Ptolemy’s world system, which he developed in his Almagest, was a geocentric model of the universe that placed the Earth at the center.

Despite his importance in the scientific community, little is known about Ptolemy’s personal life. His birthplace and date of birth, as well as his date of death, remain a mystery. However, his legacy lives on through his revolutionary works, which were far ahead of their time. His Geography, for example, was a groundbreaking book that provided detailed maps and information about the known world at the time.

The scientist’s contributions have been considered fundamental for countless generations of explorers for over 1400 years. These ancient pillars of science were so revered that no one dared to make any alterations to them.

However, with the advancement of modern science, Ptolemy’s status as a genius in fields such as geography, astronomy, and mathematics has diminished. Despite his previous authority, he no longer holds the same level of recognition.

Nevertheless, it is important to acknowledge Ptolemy’s skill in extracting intriguing ideas from the works of his predecessors, synthesizing them, and presenting them in his own unique and high-quality manner.

Ptolemy’s Geography and Almagest held a prominent position in the field of geography and astronomy for a considerable period of time. Their scientificity and infallibility went unquestioned for many years, and numerous generations of scientists gained knowledge from these works.

Geography, in terms of scientific reliability, falls short in comparison to the Almagest. The practical application of this knowledge loses its usefulness due to the limitations of theoretical calculations.

In his work, Ptolemy explicitly outlines his cartographic approach for determining astronomical values such as longitude and latitude, along with methods for projecting spherical images onto a plane.

The majority of the Geography is constructed by the author based on imprecise information and various assumptions made by navigators and travelers of the past.

Despite the author’s incorporation of mathematical principles to present the information accurately, it is challenging to categorize this ancient treatise as a genuine scientific work. Within the text, there are approximately 8 thousand names of diverse geographical entities, including cities, mountains, rivers, and islands.

Ptolemy provides a thorough depiction of the geographical aspects that were contemporary during his time. These descriptions reveal that the author recognized the overall inconsistency and inaccuracy of the coordinates he assigned to various locations in his work.

In Geography, Ptolemy utilized the measurements of distances conducted by travelers through astronomical methods as a primary source. He also addresses the reliability of such calculations within the text.

Astronomical techniques for measuring distances between different points are of utmost importance, however, the majority of geographic location data is derived from calculations made by travelers. Ptolemy believed that information could only be considered reliable when comparing data obtained from various methods (astronomical and terrestrial).

Ptolemy’s model of the Earth’s surface closely resembles modern globes. Moreover, he competently described the process of transferring the image from a sphere to a flat surface using improved projections (spherical and conical).

The treatise consists of seven books that primarily contain geographical names with coordinates. Most of the data is erroneous or inaccurate as it was sourced from the works of others.

The writings of ancient travelers greatly exaggerated the size of Asia. This artificial increase resulted in the map of the known world at that time occupying 180 degrees, when in reality it should have been 130 degrees.

In Ptolemy’s map, China is situated on the 180th meridian and takes up space from the top to the equator. The Pacific Ocean is depicted as dry land.

This is how ancient explorers envisioned the Earth. Ptolemy represented the planet as a sphere, but with its size reduced by one-fourth.

Ptolemy’s map gave Columbus the confidence that he could reach the east coast of India by sailing directly westward. Ptolemy’s work consisted of an atlas with 27 compiled maps.

It included all the graphic documents known at the time of its creation: 10 different maps of Europe, 4 maps of Africa, and 12 maps of Asia.