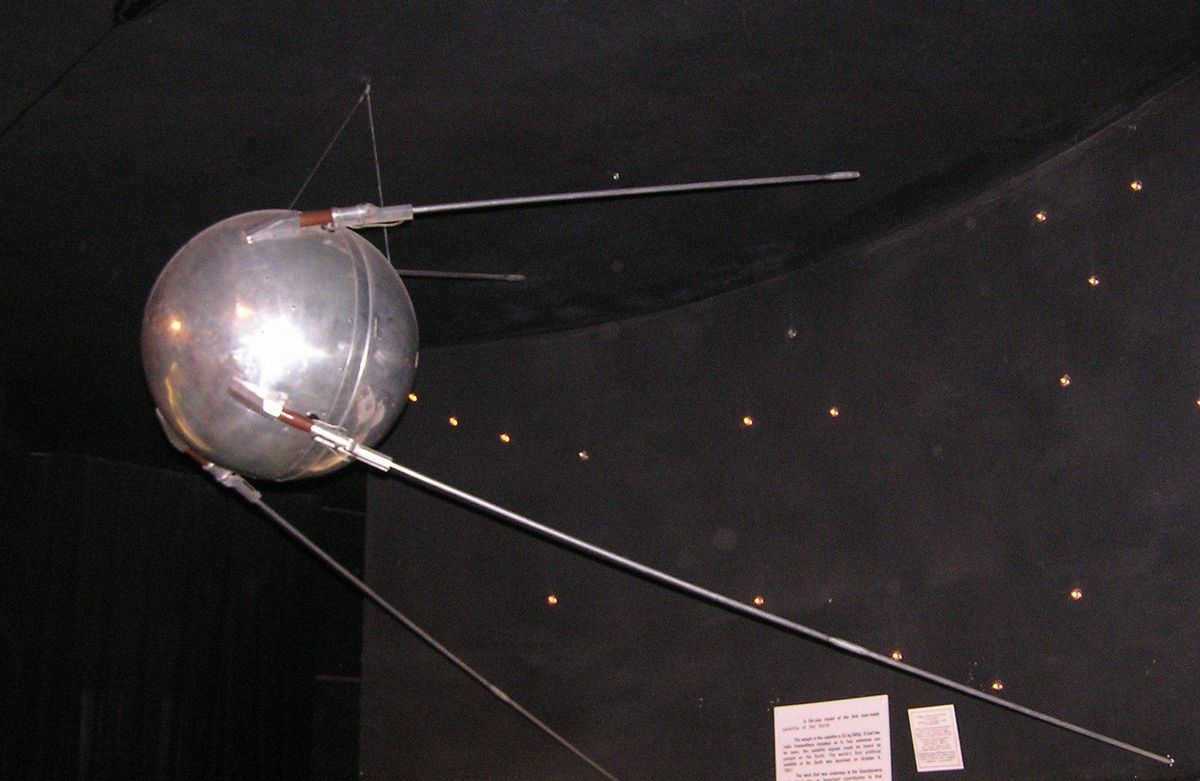

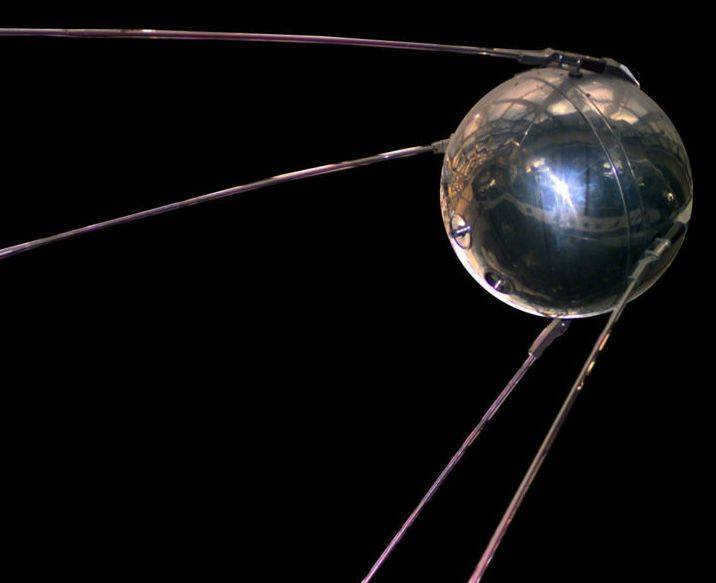

Its codename was PS-1, also known as the simplest satellite-1.

By today’s standards, it may seem primitive. However, this small metal sphere with a radio transmitter marked the beginning of the space age and demonstrated the technological prowess of the country that brought it to life.

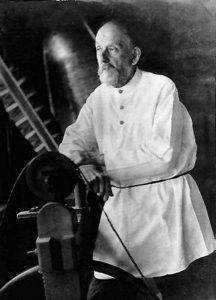

Natalia Tikhonravova, the daughter of one of the satellite’s creators, Mikhail Klavdievich Tikhonravov, shared these insights with “Rodina”. Her father was a close collaborator of S.P. Korolev, the head of the design department at OKB-1, responsible for designing all the early spacecraft during the first decade of the space age.

Preparing for the Flight. Arguments to the Point of Exhaustion

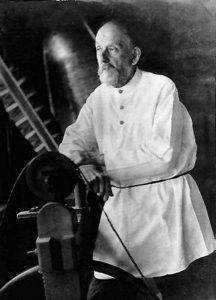

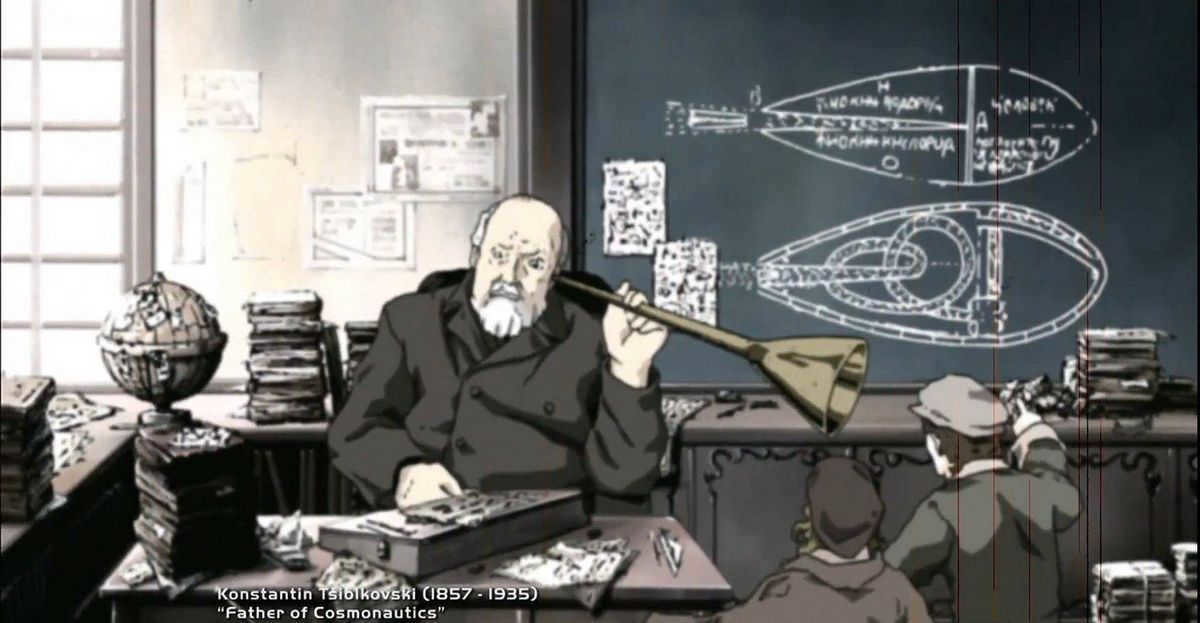

In Moscow, there stands an ancient brick house on Akademik Korolev Street. This house holds a significant historical significance, as it once served as the residence for the pioneers of Russian cosmonautics. Inside the house, you can find Mikhail Klavdievich’s office, adorned with a remarkable photograph of Tikhonravov and Tsiolkovsky.

– Back in 1934, my father embarked on a journey to Kaluga with Kleimenov, the head of the Jet Research Institute, to visit Konstantin Eduardovich. The purpose of this visit was to showcase the photographs of the first rockets that were already soaring through the skies, such as GIRD-07, GIRD-09, and GIRD-X,” Natalia Mikhailovna reveals. “My father even brought along a camera, which he had received as a prize for his remarkable contributions to the Group for the Study of Jet Propulsion (GIRD).”

Tsiolkovsky gazed at the rocket images with great excitement. “My airships pale in comparison to these rockets,” exclaimed Tsiolkovsky. He continued, “There is nothing more valuable to me than your cause. I have faith that the era of satellites will also arrive.”

It wasn’t just the visionary Tsiolkovsky who believed in satellites. Everyone involved in the development of the PS-1, including S.P. Korolev, M.V. Keldysh, N.S. Lidorenko, V.I. Lappo, B.S. Chekunov, A.V. Bukhtiyarov, and many others, shared this belief. However, it could be said that Tikhonravov himself possessed the utmost conviction.

– Discussions about the first satellite had been ongoing since the 1940s. However, they were not taken seriously,” Natalia Mikhailovna reveals. – In March 1950, during a Scientific Council meeting at the Institute, Mikhail Klavdievich was the first to discuss the immediate potential of constructing an artificial satellite to orbit the Earth, including the possibility of human space travel. The response to his ideas was insulting: “Do we have nothing better to do? This is nonsense!” Even the head of the Institute, Chechulin, dismissed the concept, stating, “I don’t consider it to be a serious matter. I believe it to be nonsense.”

It eventually led to the disbanding of the department. My father went on vacation, and upon his return, the department had vanished. He himself was demoted.

Tikhonravov’s team was comprised of a group of young individuals, with an average age ranging from 25 to 27 years old. Among them, there was only one female member named Lidochka Soldatova, who was responsible for evaluating the aerodynamic characteristics. Our aspirations revolved around interplanetary journeys, and we dedicated ourselves to hard work. At that time, I was approximately between 10 and 12 years old. I vividly recall gathering at our house, engaging in passionate debates that would often leave us hoarse. My father would ask, “So, what have you envisioned?” These dreams and ideas eventually materialized into the creation of the first satellite, followed by the second, the third, and finally culminating in Gagarin’s historic flight.

“The most influential partnership.” Korolev and Tikhonravov

– Was Korolev present at that meeting too, supporting Tikhonravov with the backing of the Experimental Design Bureau-1?

– Yes, he approached my father and said, “Come to my place, let’s have a conversation.” They agreed to share information. Tikhonravov and Korolev first met in the late 1920s in Koktebel, at the fourth All-Union glider competition. My father had a glider called “Firebird,” which was highly maneuverable and well-regarded by all who flew it. Sergei Pavlovich also had the opportunity to fly on my father’s glider. However, their true friendship blossomed in GIRD, in the basement at Sadovo-Spasskaya.

After that, their paths went in different directions: Sergei Korolev was imprisoned in 1938. Fortunately, Mikhail Tikhonravov managed to avoid this fate, although there were signs of trouble ahead. And then, a new encounter took place.

Sergey Pavlovich officially ordered NII-4 to conduct research and development on the advancement of composite missiles. This provided a significant boost to Tikhonravov’s group. Later, G.N. Pashkov, the deputy chairman of the MIC, referred to this as a “powerful and long-lasting alliance” between two passionate advocates of practical space travel, describing it as “one of the most remarkable occurrences in our history”.

In February 1953, a decision was made to develop an intercontinental ballistic missile with the primary goal of defending the country. However, Korolev quickly realized that this missile could also be used to launch a satellite into space. On May 26, 1954, he wrote: “The current progress in developing a new product with a terminal velocity of around 7000 meters per second indicates the potential for creating an artificial satellite in the near future. By reducing the payload weight, it may be possible to achieve the necessary final velocity of 8000 meters per second for the satellite.”

According to Tikhonravov’s calculations, the estimated weight of the satellite ranges from 1000 to 1400 kilograms. It would be able to carry equipment weighing around 200-300 kg, including instruments for the study of cosmic rays, the solar spectrum, and the upper atmosphere. The satellite was designed to have an orientation system, solar panels, and a return capsule to collect scientific data.

Meanwhile, a surprising announcement was made by American President Dwight Eisenhower, stating that the United States is also preparing to launch an artificial Earth satellite.

Korolev wasted no time and decided to shift focus towards developing a simpler satellite.

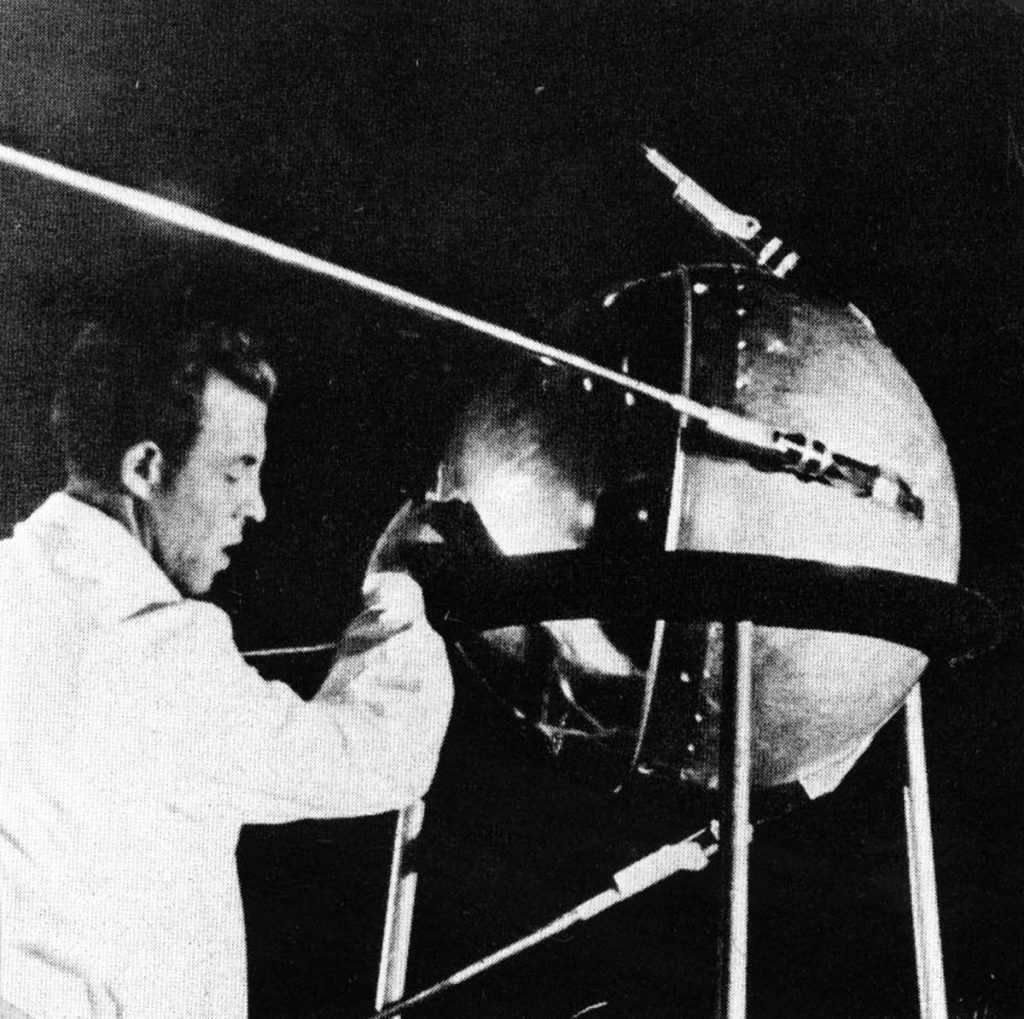

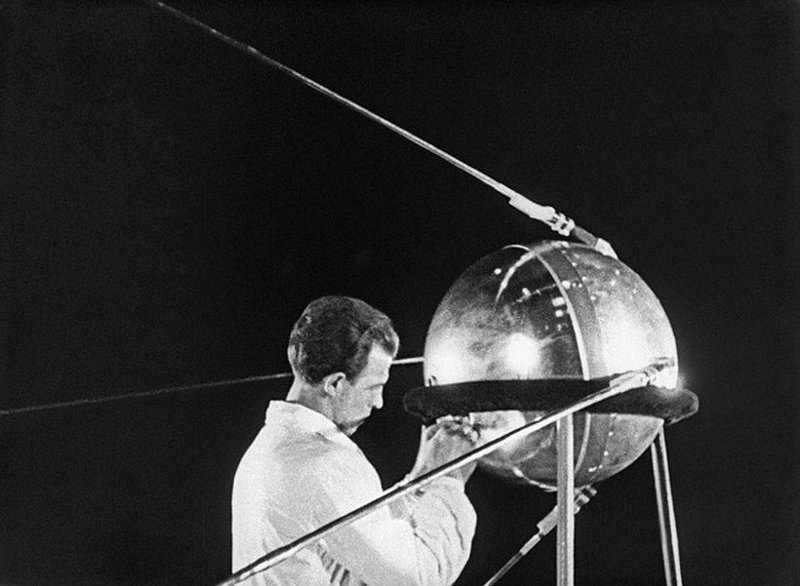

Assembly. Velvet and white gloves

Following an urgent review of the R-7 launch vehicle and its subsequent testing, a decision was made to proceed with the launch of a vehicle weighing between 80-100 kg into orbit.

– In 1956, my father joined Korolev at OKB-1, where he established his renowned department N 9. The development of satellite project sketches was in full swing. Technical requirements were issued for both oriented and non-oriented designs. The department consisted primarily of young individuals whom my father held in high regard. I believe they played a significant role in sustaining his motivation until the very end.

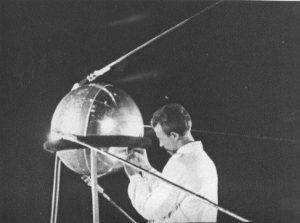

– It is said that everyone’s approach to the first satellite was not just unique, but also filled with reverence. Its hemispheres were delicately placed on a rigging draped in luxurious velvet.

– The individuals who were employed at that location were dressed in white lab coats and wore white gloves. Access to the assembly hall was strictly prohibited. An amusing incident occurred one evening when my father, who had arrived late from work, decided to visit the facility to observe the satellite. However, he too was denied entry! The staff questioned his identity and purpose, asking, “Who are you? Why are you here?” When Sergei Pavlovich learned of this incident, he became extremely angry and reprimanded them, saying, “What are you doing?! This man is the creator of the satellite!”

– I came across a statement about Tikhonravov, which described him as a genuine researcher and a brilliant engineer, but not someone who engaged in physical combat. Is this information accurate?

– Yeah, they believed that Sergei Pavlovich had a fighting spirit. However, Mikhail Klavdievich possessed a calm and composed nature. Nevertheless, he was an incredibly determined individual. He persevered in everything, even when things didn’t go as planned. He would always tell his team: “Don’t worry, it will pay off eventually. When the time comes, they will understand. The most important thing is to keep working.”

– Did he never argue with Korolev?

– Never! Everyone wonders how that was possible. After all, Sergei Pavlovich had such a fiery temperament. But he never raised his voice at Dad. They had an extraordinary relationship.

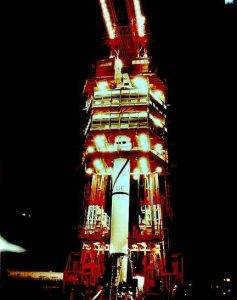

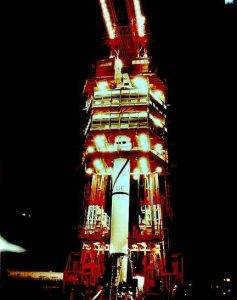

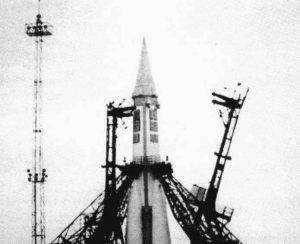

After three failed attempts, the R-7 rocket successfully took flight on August 21, 1957, delivering the payload to Kamchatka. Just ten days later, Korolev conducted the first satellite test using the same launch vehicle. In early September, the “first-born” satellite, along with the team of designers and testers, was transported to the testing site.

Launching. “Technical Pearl Harbor”

– Natalia Mikhailovna, on September 24th, Tikhonravov presented Sergei Pavlovich with a technical report on the potential launch of the PS-1. It is said that Korolev wrote a resolution: “Preserve it forever!” Where can this report be found now?

– Perhaps in the national archives. However, I believe it is more likely to be in Energia. That is where OKB-1 was located.

– Did Mikhail Klavdievich say anything to you when he returned from the test site?

– No, he didn’t say anything! It was all classified. My mom had a feeling, though, but she never asked any questions. Then, when my dad received an award, I understood it too.

The launch of the satellite and the achievement of the first orbital velocity caused a global sensation. The R-7 rocket and the first artificial satellite of the Earth became the epitome of Soviet scientific and technological achievements. One American magazine stated: “We were not expecting a Soviet satellite, so it had the impact of a new technical Pearl Harbor on America”.

A month later, on November 3, 1957, the Soviet Union launched a second satellite – weighing 508.3 kg with the dog Laika on board. It wasn’t until February 1958 that the Americans launched their first satellite.

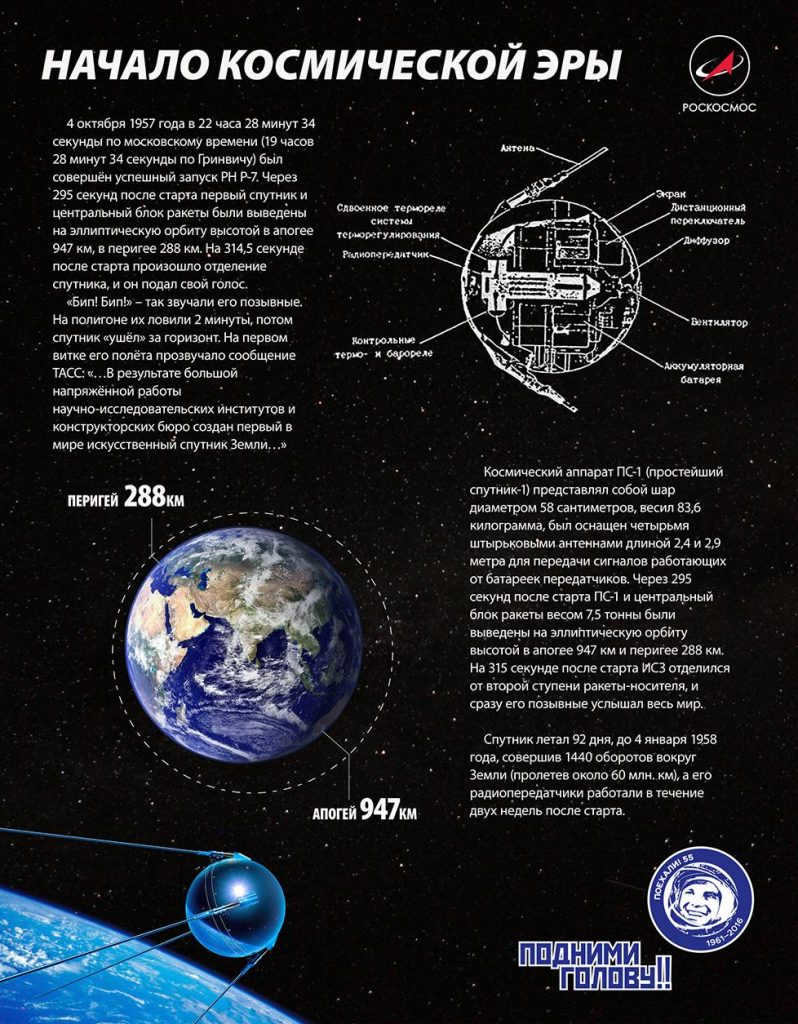

The journey began on October 4, 1957 at 22:28:34 Moscow time.

It came to an end on January 4, 1958.

After being refueled, the rocket weighed 267 tons.

The vehicle itself weighed 83.6 kg, which is only 0.03% of the rocket’s total mass.

The maximum diameter of the rocket was 0.58 m.

During its mission, it made 1440 orbits around the Earth, covering a distance of approximately 60 million km.

Each revolution took 96 minutes and 10.2 seconds.

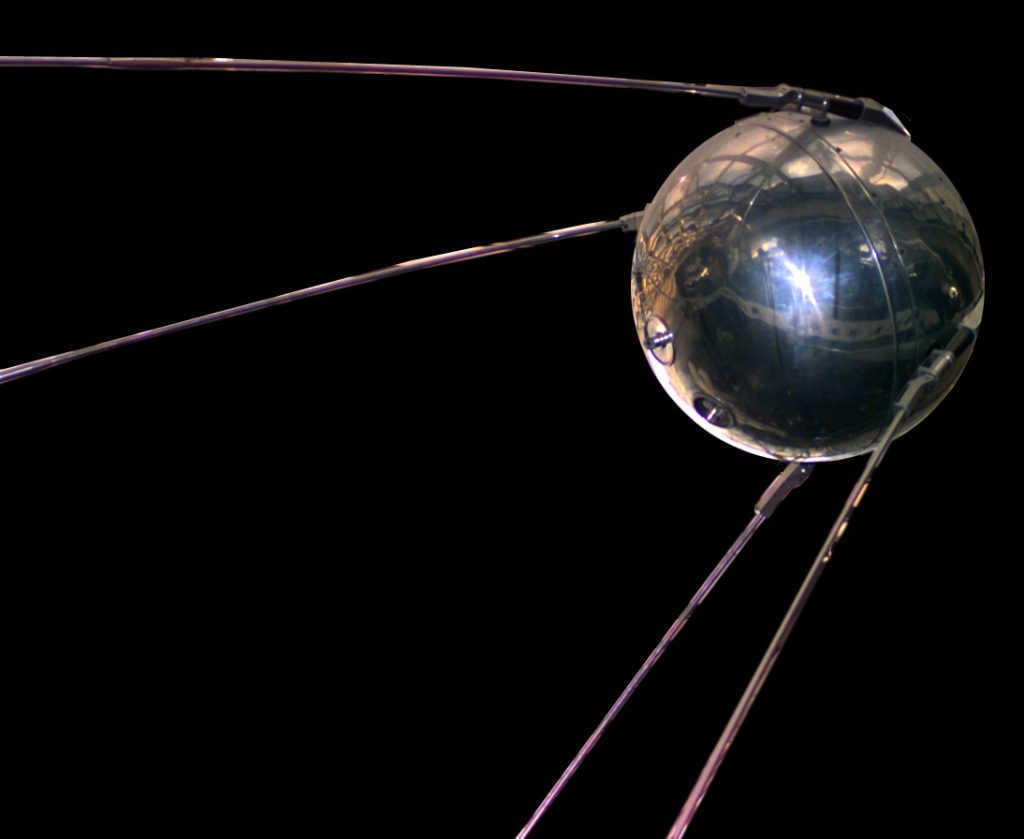

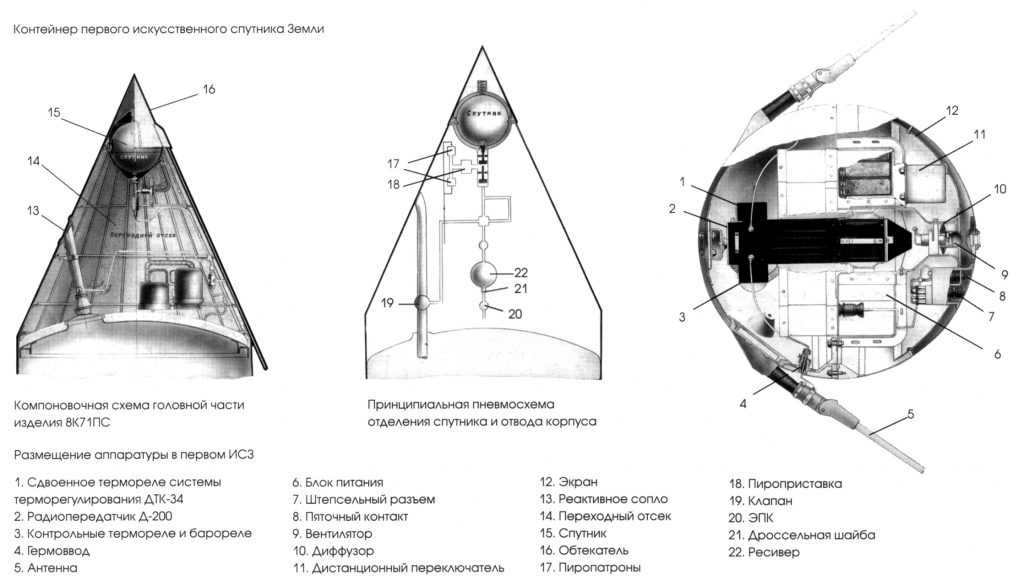

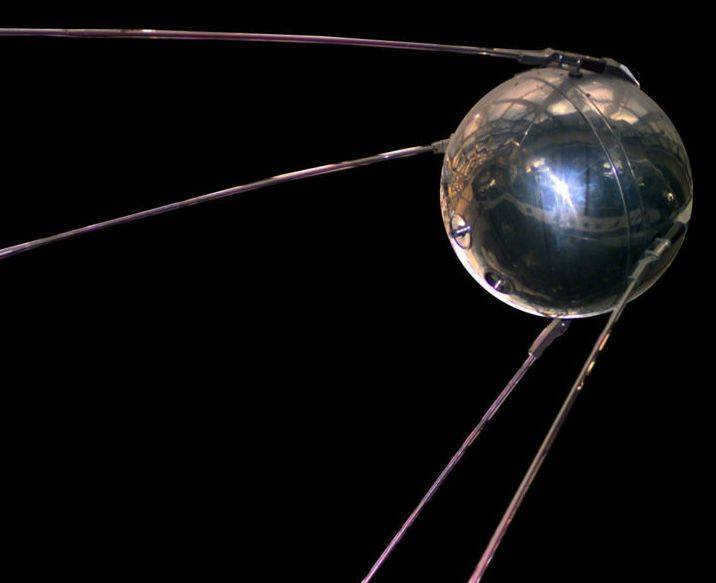

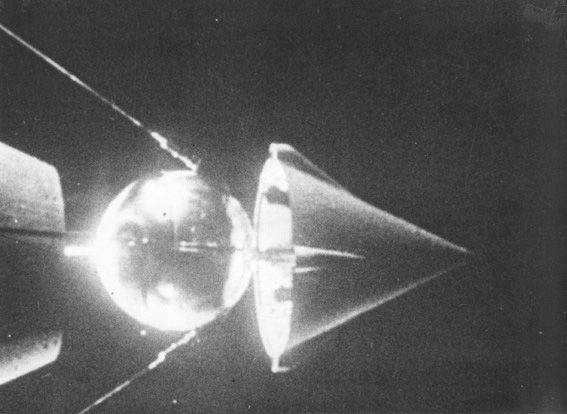

The satellite was constructed using two 58 cm diameter hemispheres, each made of 2 mm thick AMr-6 aluminum alloy. These hemispheres were connected by 36 bolts, which also secured the docking spars. To ensure optimal performance, the surface of the satellite was meticulously polished to enhance sunlight reflection and prevent overheating. Great care was taken to avoid even the slightest scratch on the satellite’s exterior.

Inside the satellite, nitrogen was used to maintain a constant temperature of 20-30 C. This controlled environment was crucial for the proper functioning of the satellite’s components.

On the upper half-shell of the satellite, there were four antennas. Two of these antennas measured 2.4 m in length, while the other two were 2.9 m long. A special spring mechanism was employed to separate these antennas in orbit, positioning them at an angle of 35 degrees from the satellite’s longitudinal axis. This configuration allowed for optimal signal reception and transmission.

Despite the absence of scientific equipment on board the satellite, the scientists managed to gather significant data. They conducted calculations and confirmed basic technical solutions. They also conducted studies on the transmission of radio waves through the ionosphere emitted by the satellite transmitters, experimentally determined the density of the upper atmosphere through satellite braking, and examined the working conditions of the equipment.

During the rocket launch, one of the engines experienced a delay. The unit switched to the appropriate mode less than a second before the scheduled control time. Any later and the launch would have been automatically canceled.

At the 16th second of the mission, a second mishap occurred when the fuel supply control system malfunctioned, causing a higher consumption of kerosene. As a result, the central engine shut down 1 second earlier than anticipated, leading to the rocket and satellite being placed in an orbit with an apogee approximately 80-90 km lower than the intended orbit.

Why choose a balloon?

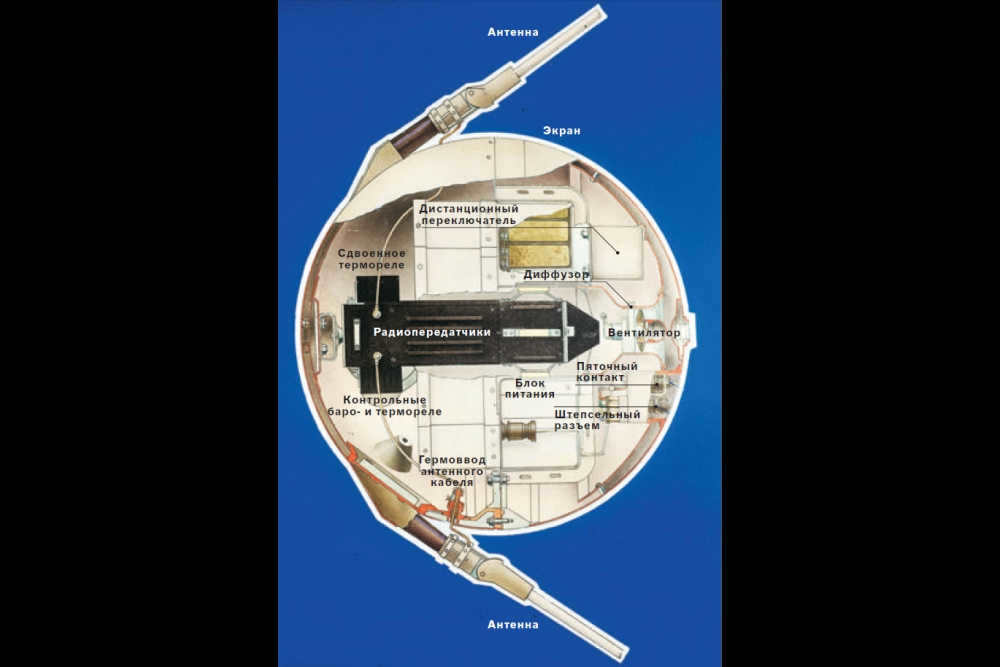

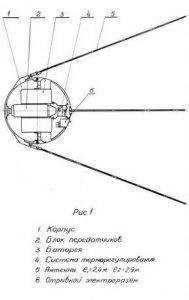

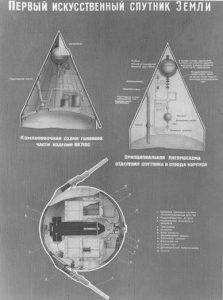

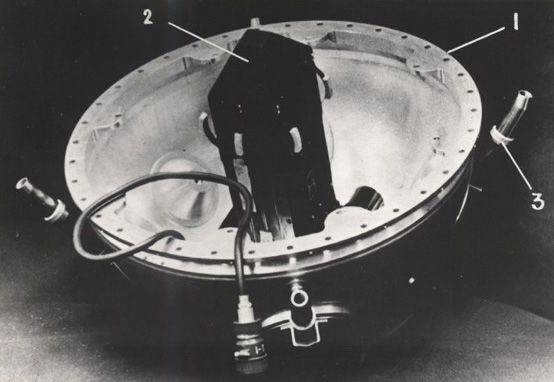

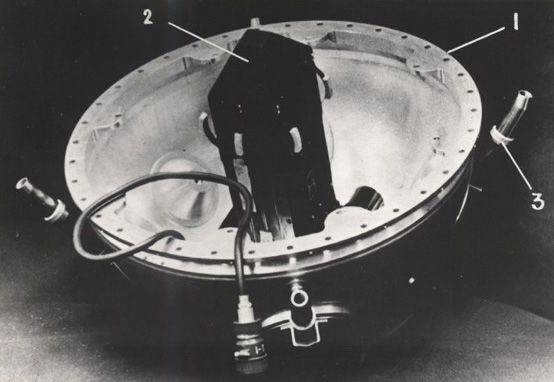

In the beginning, the initial plan was to create a satellite with a conical shape and a spherical bottom. However, the designers quickly realized that a balloon would be more suitable. By using a balloon with a smaller surface area, they could maximize the internal volume. Inside the balloon, they placed two radio transmitters with emission frequencies of 20.005 and 40.002 MHz, a silver-zinc battery block, a fan, a thermorelay and air duct, an onboard electrical automation device, temperature and pressure sensors, and an onboard cable network.

The signals from the satellite were in the form of telegraphic packages (“beeps”) that lasted between 0.2 and 0.6 seconds. The signal had an emission power of 1 watt. The frequency and pause between the “beeps” were determined by sensors that monitored pressure and temperature, allowing for easy control of the satellite’s hull tightness. The radio transmission of these signals lasted for a period of three weeks.

What caused the tumbling motion?

During that period, the satellite lacked a proper orientation system, so it would be inaccurate to envision the PS-1 moving with its hull facing forward and antennas facing backward. It is more probable that it was tumbling while in orbit.

Natalia Tikhonravova is a renowned scientist in the field of biology. She holds a Ph.D. in Biological Sciences and currently serves as a leading researcher at the State Scientific Center of the Russian Federation – Institute of Medical and Biological Problems of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

In the age of space exploration, it has become a familiar concept for us. Nevertheless, as we witness the colossal reusable rockets and space orbital stations of today, it is easy to overlook the fact that the initial launch of a spacecraft occurred a mere 60 years ago.

On October 4, 1957, the inaugural artificial satellite was successfully sent into orbit.

Basic details

Which country was responsible for launching the inaugural man-made satellite? – The Soviet Union. This inquiry holds significant significance as it sparked the infamous competition known as the space race between the United States of America and the Soviet Union.

What was the title of the initial man-made satellite in the world? – Due to the fact that such vehicles had never existed prior to this, Soviet scientists believed that the name “Sputnik-1” was highly suitable for this vehicle. The apparatus is coded as PS-1, which represents “Simple Sputnik-1”.

Origin and Background

Joseph Stalin issued a decree on May 13, 1946, which marked the beginning of the Soviet Union’s rocket industry. Taking charge as the chief designer of ballistic missiles was Sergei Korolev, who led a team of scientists in the development of various intercontinental ballistic missiles such as the R-1, R-2, R-3, and others over the course of the next decade.

In 1948, a presentation on composite rockets and the results of calculations was given by rocket designer Mikhail Tikhonravov to the scientific community. The report stated that the newly developed 1000-kilometer rockets had the potential to reach significant distances and even launch an artificial satellite into Earth’s orbit. Unfortunately, this statement was met with criticism and not taken seriously. As a result, Tikhonravov’s department at NII-4 was disbanded due to their perceived irrelevant work. However, thanks to the efforts of Mikhail Klavdievich, the department was reassembled in 1950. It was during this time that Mikhail Tikhonravov began openly discussing the mission to successfully launch a satellite into orbit.

Following the development of the R-3 ballistic missile, its capabilities were unveiled, demonstrating that the missile not only had the ability to strike targets at a range of 3000 km, but also to launch a satellite into orbit. By 1953, the scientists had successfully convinced the highest-ranking officials that launching an orbital satellite was indeed achievable. Consequently, the military leaders recognized the potential for developing and launching an artificial Earth satellite (EAS). As a result, in 1954, a decree was issued to establish a dedicated team at NII-4 led by Mikhail Klavdievich, tasked with designing the satellite and outlining the mission. During the same year, Tikhonravov’s team presented a comprehensive space exploration program, which encompassed the launch of an ISV and ultimately culminated in a moon landing.

In 1955, the Leningrad Metal Works was visited by a delegation of the Politburo led by Khrushchev. During their visit, they observed the completion of the construction of the R-7 two-stage rocket. The impression made by the delegation led to the signing of a resolution to develop and launch a satellite into Earth’s orbit within the following two years. The design process for the satellite commenced in November 1956, and by September 1957, the Sputnik-1, a basic model, had successfully undergone testing on a vibration test bench and in a thermal chamber.

The question of who invented Sputnik-1 cannot be definitively answered. The first Earth satellite was developed under the guidance of Mikhail Tikhonravov, and the creation of the launch vehicle and the satellite’s launch into orbit was led by Sergei Korolev. However, numerous scientists and researchers contributed to both projects.

Launch history

The first satellite PS-1 was successfully launched in February 1955

In February 1955, the leadership approved the establishment of the Research and Development Test Site No. 5 (later Baikonur), which was to be located in the Kazakhstan desert. The test site was used for testing the first ballistic missiles of the R-7 type. However, after five test launches, it became clear that the massive ballistic missile head could not withstand the temperature load and needed to be reworked, which would take about six months. As a result, S. P. Korolev requested two rockets from Nikita Khrushchev for an experimental launch of the PS-1. In September 1957, the R-7 rocket arrived at Baikonur with a lightened head section and a transition for the satellite. The unnecessary hardware was removed, resulting in a reduction of 7 tons in the rocket’s mass.

On October 2, S. P. Korolev gave his approval for the satellite’s flight testing and sent a notification of readiness to Moscow. Despite receiving no response from Moscow, Sergei Korolev made the decision to launch the Sputnik launch vehicle (R-7) from PS-1 to the designated launch position.

The reason behind the leadership’s insistence on launching the satellite into orbit during this time is due to the International Geophysical Year, which took place from July 1, 1957 to December 31, 1958. This year-long event involved 67 countries collaborating on geophysical research and observations according to a unified program.

The first artificial satellite was launched on October 4, 1957. Additionally, on the same day, the VIII International Congress of Astronautics opened in Barcelona, Spain. Due to the classified nature of the work being done, the leaders of the USSR’s space program were not publicly disclosed. However, Academician Leonid Ivanovich Sedov informed the Congress about the groundbreaking satellite launch. As a result, Sedov was widely regarded as the “father of Sputnik” by the global community.

The Flight’s Historical Background

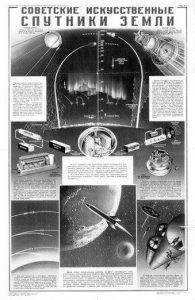

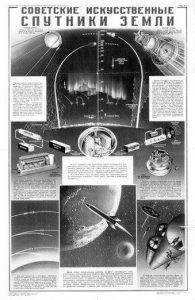

Infographics about the PS-1 satellite

A rocket carrying the satellite was launched from NIIP No. 5 (Baikonur) at 22:28:34 Moscow time. 295 seconds later, the rocket’s central unit and the satellite were placed in an elliptical orbit around the Earth (apogee – 947 km, perigee – 288 km). After another 20 seconds, PS-1 separated from the rocket and transmitted a signal. These signals, which were in the form of “Beep! Beep!” sounds, were detected at the test site for 2 minutes until Sputnik-1 disappeared from view. On the first orbit of the spacecraft around the Earth, the Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union (TASS) announced the successful launch of the world’s first satellite.

Following the receipt of signals from the PS-1, comprehensive information started to come in regarding the spaceship, which seemed to be on the verge of failing to achieve initial space velocity and establish an orbit. The cause of this issue was an unexpected malfunction in the fuel control system, resulting in one of the engines falling behind. It was just a hair’s breadth away from complete failure.

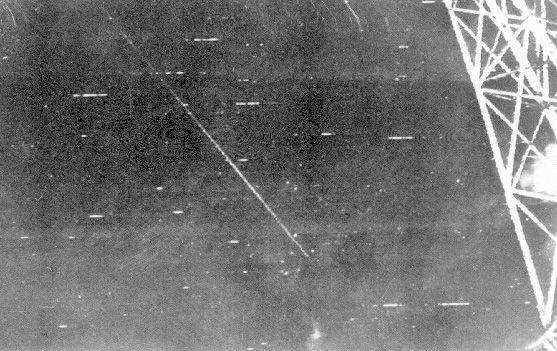

Despite the successful achievement of an elliptical orbit and a 92-day journey with 1440 revolutions around the planet, PS-1 eventually met its demise. The cause of this unfortunate event was the decrease in speed due to atmospheric friction. As a result, Sputnik-1 began to descend and eventually burned up in the denser layers of the atmosphere. Interestingly, many individuals were able to witness a shining object traversing the sky during this time. However, without the aid of specialized optics, the shiny body of the satellite remained invisible. In reality, this object was the second stage of the rocket, which was also in orbit and rotating alongside the satellite.

The initial satellite. An illustration by an artist.

The Soviet Union’s inaugural launch of a man-made satellite resulted in an unparalleled surge of national pride and dealt a significant blow to the reputation of the United States. A passage from the United Press reads: “The majority of discussions surrounding man-made satellites originated from the United States. However, it was Russia who ultimately accomplished the endeavor…”. Contrary to misconceptions regarding the technological inferiority of the USSR, it was a Soviet invention that became the pioneering satellite, and its signal could be detected by any amateur radio enthusiast. The launch of the first satellite from Earth marked the dawn of the space era and ignited a competition for supremacy in space exploration between the Soviet Union and the United States.

Only 4 months later, on February 1, 1958, the United States successfully sent its own satellite, Explorer 1, into space. This remarkable achievement was made possible by the dedicated efforts of a team of scientists led by Wernher von Braun. Despite being significantly lighter than the PS-1 satellite and carrying only 4.5 kg of scientific equipment, Explorer 1 was the second satellite launched by the U.S. and did not generate the same level of public interest and excitement.

Scientific findings from the PS-1 mission

The primary objectives of the SAR-1 launch encompassed:

- Evaluating the technical capabilities and validating the calculations employed for the successful deployment of the satellite;

- Investigating the ionosphere. Prior to the spacecraft launch, the ionosphere was largely unexplored due to the reflection of radio waves sent from Earth. With the satellite emitting radio waves from space and traversing the atmosphere to the Earth’s surface, scientists can now commence studying the ionosphere.

- Assessing the density of the upper atmosphere by observing the spacecraft’s deceleration rate caused by friction against the atmosphere;

- Conducting research on the impact of the outer space environment on hardware, and identifying optimal conditions for hardware functioning in space.

Listening to the sound emitted by the First Satellite

Despite the absence of scientific instruments on board the satellite, valuable insights were obtained by tracking its radio signal and analyzing its characteristics. For instance, a team of scientists from Sweden utilized the Faraday effect to measure the electronic composition of the ionosphere. This effect, which states that the polarization of light changes when it traverses a magnetic field, proved instrumental in their research. Additionally, a group of Soviet scientists from Moscow State University devised a technique to observe the satellite with precise determination of its coordinates. By studying the behavior of its elliptical orbit, they were able to determine the atmospheric density in the region of its orbital altitude. Surprisingly, the observed increase in atmospheric density led to the development of a theory on satellite braking, which made significant contributions to the field of astronautics.

Curious details

Monument in Moscow dedicated to the pioneers of the world’s inaugural man-made satellite.

A video showcasing the groundbreaking satellite.

Displayed prominently in the front is the historic First Sputnik, an unparalleled feat of technology during its era.

Meanwhile, standing in the background are the esteemed researchers and innovators from the Institute of Cosmonautics and Information Technologies, who played integral roles in the development of the inaugural satellite, as well as advancements in atomic weaponry, space exploration, and technological progress.

If you are unable to decipher the image, here are the names:

Valentin Semyonovich Etkin – he specialized in using remote radio-physical methods to observe the Earth’s surface from space.

Pavel Efimovich Elyasberg – he played a leading role in the launch of the first Artificial Earth Satellite, focusing on determining orbits and predicting satellite motion based on measurement results.

Yan Lvovich Ziman – his doctoral thesis, defended at MIIGAiK, focused on satellite orbit selection.

Yakov Borisovich Zeldovich – a renowned theoretical physicist who received the Stalin Prize of the 1st degree multiple times for his work related to the atomic bomb. He was also honored as a Three-time Hero of Socialist Labor.

Georgy Petrov – he, along with S.P.Korolev and M.V.Keldysh, played a pivotal role in the early days of space exploration.

Iosif Samuilovich Shklovsky – he is considered the founder of the modern astrophysics school.

Konstantin Iosifovich Gringauz – the pioneer of the artificial Earth satellite, launched in 1957, carried a radio transmitter developed by a scientific and technical team led by K. I. Gringauz.

Yuri Ilyich Galperin – conducted research on magnetospheric phenomena.

Semyon Samoilovich Moiseev – focused on plasma and hydrodynamics studies.

Vasily Ivanovich Moroz – dedicated his work to the physics of planets and small celestial bodies within the solar system.

October 4, 1957 marked a significant milestone in human history, as it heralded the beginning of a new era – the space age. On this day, the first artificial satellite (ISV), Sputnik-1, was launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome. Although it weighed a mere 83.6 kilograms, the successful delivery of even this small “crumb” into orbit was a monumental achievement at that time.

I believe that there is not a single person in Russia who is not aware of the identity of the first human to venture into space.

The situation surrounding the first satellite is rather intricate. Numerous individuals are unaware of the country to which it was attributed.

Thus, a new era in scientific exploration commenced, along with the iconic space race between the USSR and the USA.

The dawn of rocket science can be traced back to the early years of the previous century, starting with theoretical concepts. During this time, the renowned scientist Tsiolkovsky, in his article on jet propulsion, actually forecasted the advent of satellites. Despite having numerous students who went on to popularize his concepts, many dismissed him as nothing more than a visionary.

Following that, a new era began for the country, bringing with it a multitude of tasks and challenges, excluding the realm of rocket science. However, after a span of twenty years, Friedrich Zander and the now renowned aviation engineer Korolenko joined forces to establish a collective dedicated to the exploration of jet propulsion. Subsequently, a series of events unfolded, ultimately culminating in the monumental achievement of launching the first satellite into outer space three decades later, and eventually leading to the emergence of a man:

1933 – commencement of the inaugural rocket propelled by a jet engine;

1943 – invention of the German FAU-2 rockets;

1947-1954 – successful launches of the P1-P7 rockets.

The device was prepared by 7 PM on a mid-May day. Its design was relatively straightforward, featuring a pair of beacons that facilitated the measurement of its flight paths. A curious fact is that despite Korolev notifying Moscow of the satellite’s readiness for launch, he did not receive any response. Undeterred, he took it upon himself to position the satellite for liftoff.

S.P.Korolev oversaw the preparation and launch of the satellite. It completed 1440 complete orbits in 92 days before disintegrating upon reentry into the Earth’s dense atmosphere. The radio transmitters remained functional for a fortnight following the launch.

Everyone is aware of the advantages and disadvantages of this situation, and it is not to be taken lightly.

The importance of understanding this situation cannot be overstated. When humanity first lays eyes on an artificial satellite, it should evoke feelings of positivity. What better way to accomplish this than with a balloon? Its shape closely resembles the celestial bodies in our solar system, making it relatable and familiar. People will see the satellite as a visual representation, a symbol of the space age!

In my opinion, it is crucial to equip the satellite with transmitters that can be received by radio enthusiasts across all continents. The satellite’s orbital trajectory should be carefully calculated so that anyone on Earth can witness its flight using basic optical devices. This will ensure that the Soviet satellite’s journey is visible to all.”

On the morning of October 3, 1957, a gathering took place near the assembly and test building, consisting of scientists, designers, and members of the State Commission, all of whom were involved in the launch. Their purpose was to witness the transportation of the two-stage rocket-space system known as “Sputnik” to the launch pad.

The gates made of metal swung open, revealing a sight that resembled a locomotive pushing out the rocket from its position on a special platform. In a display of high regard for the labor that had brought about this engineering marvel, Sergei Pavlovich took off his hat, setting a new tradition that was quickly followed by others.

Korolev, positioned a few steps behind the rocket, paused and adhered to the old Russian custom by saying, “Well, with God!”

The era of space exploration was just hours away. What did Korolev and his team anticipate? Would October 4th be the triumphant day he had longed for? The night sky, adorned with countless stars, seemed to be within reach. And everyone gathered at the launch site couldn’t help but gaze at Korolev. What was going through his mind as he looked up into the dark expanse, twinkling with countless nearby and distant stars? Perhaps he was recalling the words of Konstantin Eduardovich Tsiolkovsky: “The first monumental leap for humanity is to venture beyond the atmosphere and become a satellite of the Earth”?

The State Commission’s final meeting before the launch took place just over an hour beforehand. S.P. Korolev took the floor and everyone anticipated a detailed report, but the chief designer kept it brief: “The launch vehicle and satellite have successfully passed all tests. I propose that we proceed with the launch of the space rocket complex as scheduled, today at 22:28.”

“THE FIRST ARTIFICIAL SATELLITE OF THE EARTH, THE SOVIET SPACECRAFT, HAS BEEN LAUNCHED INTO ORBIT.”

The launch was conducted from the USSR Defense Ministry’s 5th Tyura-Tam research range, using a Sputnik launch vehicle based on the P7 intercontinental ballistic missile.

At 22:28:34 Moscow time on Friday, October 4th (19:28:34 GMT), a successful launch occurred.

295 seconds after liftoff, the PS-1 and the central block (II stage) of the 7.5-ton rocket were placed into an

elliptical orbit with an altitude of 947 km at apogee and 288 km at perigee. The apogee was situated in the Southern Hemisphere, while the perigee was located in the Northern Hemisphere. 314.5 seconds after liftoff, the protective cone was discarded and Sputnik separated from the second stage of the launch vehicle, emitting its distinctive sound. “Beep! Beep!” – That was the sound of its call sign.

They observed it for 2 minutes at the test site before Sputnik disappeared over the horizon. People at the cosmodrome rushed out into the street, cheering “Hurrah!” and congratulating the designers and military personnel.

And even on the first rotation, a TASS message was transmitted:

“Thanks to the tremendous efforts of research institutes and design bureaus, the world’s inaugural man-made satellite, the artificial Earth satellite, has been successfully developed.”

It was only after capturing the initial signals from Sputnik that the analysis of telemetry data yielded results, revealing that only a tiny fraction of a second stood between success and failure. Prior to its launch, the engine in Block G experienced a delay, and the timing for entering the designated mode was strictly regulated, with automatic cancellation of the launch if that time was exceeded.

The unit switched to the mode just before the control time, less than a second had passed. On the 16th second of the flight, there was a failure in the tank emptying system (TES), resulting in increased consumption of kerosene and causing the central engine to shut down 1 second earlier than expected. According to B.E. Chertok’s memoirs: “It was only a little more, and the first space velocity might not have been achieved.

But winners are not judged! The great achievement was accomplished!”

Sputnik 1 had an orbital inclination of approximately 65 degrees, which meant that it flew roughly between the Arctic Circle and the South Polar Circle, shifting 24 degrees in longitude during each revolution due to the rotation of the Earth.

The original orbital period of Sputnik 1 was 96.2 minutes, but it gradually decreased as the satellite’s orbit decreased. For example, after 22 days, it became 53 seconds shorter.

The Story behind its Creation

The launch of the first satellite was the result of extensive work by scientists and designers, with scientists playing a crucial role.

Here are some of their names:

Valentin Semyonovich Etkin – He pioneered the use of remote radio-physical methods to study the Earth’s surface from space.

Pavel Efimovich Elyasberg – He spearheaded the efforts to determine the satellite’s orbits and predict its motion based on measurement results.

Yan Lvovich Ziman – His PhD thesis, defended at MIIGAiK, focused on orbit selection for satellites.

Georgy Petrov, along with S.P.Korolev and M.V.Keldysh, played a crucial role in the development of space exploration.

Iosif Samuilovich Shklovsky is renowned for being the pioneer of modern astrophysics.

Georgy Stepanovich Narimanov made significant contributions to the field of navigation and ballistic support in controlling artificial earth satellites.

Konstantin Iosifovich Gringauz and his scientific and technical group were responsible for creating the radio transmitter that was onboard the first artificial Earth satellite launched in 1957.

Yuri Ilyich Galperin conducted groundbreaking research on magnetospheres.

Semyon Samoilovich Moiseev made notable contributions to the fields of plasma and hydrodynamics.

Vasily Ivanovich Moroz focused his research on the physics of planets and small bodies within the solar system.

The structure of the satellite included two power hemispherical shells made of aluminum-magnesium alloy AMg-6, each with a diameter of 58.0 cm and a thickness of 2 mm. These shells were connected by 36 M8×2.5 studs and docking spars. Prior to its launch, the satellite was pressurized with dry gaseous nitrogen at a pressure of 1.3 atmospheres. To ensure a tight seal, a vacuum rubber gasket was used. Additionally, the upper half-shell of the satellite had a smaller radius and was protected by a 1 mm thick hemispherical outer shield, which served as insulation against thermal effects.

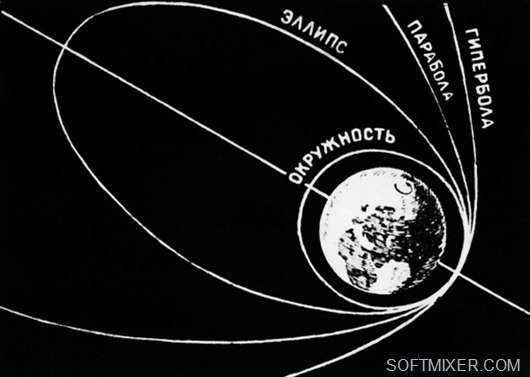

A diagram illustrating the path of the initial Earth satellite, as depicted in the article “Soviet Aviation” from 1957.

In the annals of human history, a pivotal moment occurred on October 4, 1957, when the dawn of the space age commenced. Ingeniously crafted by the skilled hands of Earth’s engineers, a groundbreaking creation was launched into orbit. It was christened Sputnik.

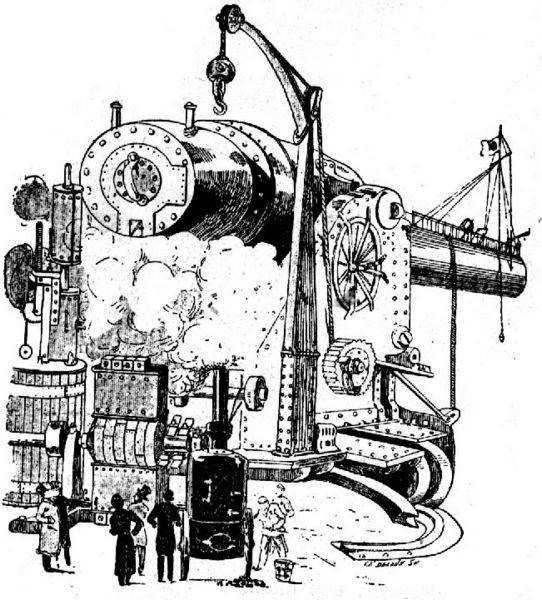

The concept of a man-made satellite orbiting the Earth has been around for a long time. Even as far back as 1687, in his book “The Mathematical Beginnings of Natural Philosophy,” Isaac Newton used the idea of a gigantic cannon to explain the possibility of launching a projectile into a stable orbit. Newton suggested envisioning a mountain with its peak outside the Earth’s atmosphere, and a cannon positioned at the very top, firing horizontally. By increasing the power of the cannon’s charge, the projectile would travel farther away from the mountain. Eventually, with enough power, the projectile would reach a velocity where it would no longer fall back to Earth, but instead, orbit around the planet. This velocity is now known as the first cosmic velocity, which for Earth is approximately 7.91 kilometers per second.

Both scientists and science fiction writers later utilized Newton’s metaphorical illustration. Jules Verne, a renowned science fiction author, described the technical implementation of “Newton’s gun” in his novel “500 Million Begumas” (1879).

A massive French cannon designed specifically for propelling objects into space.

The visionary Tsiolkovsky gazes into the future.

The pioneers of theoretical astronautics discussed extensively the importance of launching an artificial satellite around the Earth. However, they justified this significance in various ways. Our fellow countryman Konstantin Tsiolkovsky suggested launching a crewed rocket into a circular orbit to immediately embark on human space exploration.

German Hermann Oberth proposed constructing a large orbital station using carrier rocket stages, which could address the tasks of military reconnaissance, marine navigation, geophysical research, and information message relay.

According to numerous scientists and science fiction authors, there was a consensus that the primary purpose of Earth’s artificial satellite would be to serve as a transfer hub for interplanetary spacecrafts en route to the Moon, Mars, and Venus. After all, why should a spacecraft carry all the necessary fuel for acceleration into orbit, when it could simply refuel from the satellite?

Furthermore, there were also ideas to equip the future satellite with a telescope, allowing astronomers to directly observe distant celestial objects from orbit without any atmospheric distortions.

An artificial satellite that orbited the Earth (original artwork from V. Nikolsky’s book “In a Thousand Years”).

An artificial satellite that orbited the Earth (original artwork from V. Nikolsky’s book “In a Thousand Years”).  A satellite inhabited by humans, circling the Earth (original cover for the American edition of Otto Geil’s novel “The Moonstone”).

A satellite inhabited by humans, circling the Earth (original cover for the American edition of Otto Geil’s novel “The Moonstone”).

This type of artificial satellite is described in Otto Geil’s novel “Moonstone” (1926), Vadim Nikolsky’s “In a Thousand Years” (1927), and Alexander Belyaev’s “The Star of the KETs” (1936).

Nevertheless, as time went by, the construction of a delivery system for placing satellites into orbit proved to be an insurmountable challenge. The development of massive cannons required an immense amount of labor and resources, making it both prohibitively expensive and time-consuming. Meanwhile, the smaller rockets that had been used in abundance prior to World War II were incapable of achieving the necessary velocity to reach outer space, even in theory.

Due to the absence of a carrier, a variety of unique projects emerged. For instance, in 1944, Major General Georgy Pokrovsky published an article titled “A Novel Earth Satellite”, where he proposed launching a metallic satellite using a directed explosion. He recognized, of course, that only “various unstructured masses of metals” would enter orbit after such an explosion. Nevertheless, he firmly believed that humanity also required such an experience, as observing the movement of an “unstructured” object would provide a wealth of new information about the processes occurring in the upper layers of the atmosphere.

It is common knowledge that the Third Reich was responsible for the development of the first significant liquid fuel rockets. It was during this time that discussions began regarding the potential use of these rockets for satellite launches.

Historical evidence suggests that at the German rocket center Penemünde, there was a proposal to commemorate the first space explorers by placing their embalmed bodies inside glass spheres and launching them into orbit around the Earth.

The development of astronautics was predetermined by the appearance of the powerful “Fau-2” rockets.

In March 1946, experts from the U.S. Air Force prepared an “Initial Design of an Experimental Spacecraft for Orbiting the Earth”. This document marked the first serious attempt to assess the potential for creating a spacecraft that would serve as a satellite to orbit the Earth.

Even though the exact timing of the start of space activities remains uncertain, the project’s introduction highlights two undeniable facts: 1) Utilizing a spacecraft with the right tools will likely prove to be an incredibly powerful tool for scientific research in the 20th century. 2) The launch of a satellite by the United States would captivate the world’s imagination and have a profound impact on global affairs, comparable to the detonation of the atomic bomb.

In a research report titled “Rocket Vehicle – Earth Satellite: Political and Psychological Problems,” American scientist Kecskemeti presented an analysis on the potential political consequences of launching an artificial Earth satellite in the United States for military intelligence purposes. This report, presented on October 4, 1950, seven years before the first ISV launch, demonstrates that military experts in the early 1950s were fully aware of the political and military significance of satellite launches. Instead of mere glass spheres containing space conquerors, designers envisioned intricate orbital groupings that could track the territories of potential adversaries.

"Fau-2" made its debut at the White Sands range, marking the dawn of American astronautics.

During the 4th International Astronautical Congress in Zurich in 1953, Fred Singer from the University of Maryland openly announced that the United States possessed the necessary conditions to develop an artificial Earth satellite, codenamed "MAUS" ("Minimum Orbital Unmanned Satellite of Earth"). Singer’s proposed satellite would consist of a self-contained instrumentation and measurement system enclosed in a solid balloon, which would detach from the third stage of a composite launch vehicle once it reached a predetermined altitude. The satellite’s orbit, at an altitude of 300 kilometers, would traverse both the Earth’s poles.

At the launch, Wernher von Braun’s rocket was present.

A meeting took place on June 25, 1954, at the Naval Research Office building in Washington, D.C. The meeting was attended by prominent American rocket scientists: Wernher von Braun, Professor Singer, Professor Whipple from Harvard, David Young from Aerojet, and others. The main topic of discussion was whether it would be feasible to launch a large satellite into a 320-km-high orbit in the near future. The term “near future” referred to a period of 2-3 years.

According to Wernher von Braun, the historical launch could be achieved at an earlier time by utilizing the Redstone rocket as the initial stage and multiple bundles of Loki rockets as subsequent stages. The major benefit of this approach was the ability to make use of existing rockets. As a result, the Orbiter project came into existence. The satellite’s launch was initially planned for the summer of 1957.

The launch of the first artificial satellite, Sputnik, in 1957, marked a significant milestone in space exploration. However, it is important to note that the American satellite, Explorer 1, was also successfully launched by Wernher von Braun.

During this time, various other satellite projects were being developed as well.

In fact, on July 29, 1955, the White House officially announced its plans to launch a satellite as part of the Navy’s Vanguard program. The proposed launch involved a three-stage carrier, consisting of a modified Viking rocket as the first stage, a modified Aerobee rocket as the second stage, and a solid-fueled third stage. The Vanguard satellite was initially designed to weigh 9.75 kg and was equipped with measuring instruments. Furthermore, it had a small power source and even a camera on board, allowing it to transmit color images back to Earth.

The American Vanguard satellite had the potential to become the frontrunner in space exploration, but unfortunately, it never got the chance to prove its worth. Tragically, on December 6, 1957, the rocket carrying Vanguard-1 exploded during its launch, dashing the hopes of many who had eagerly anticipated its success.

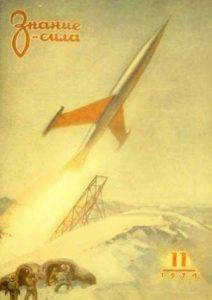

Front page of the futuristic edition of “Knowledge is Power” magazine

In November 1954, an extraordinary futuristic edition of the magazine “Knowledge is Power” was released, dedicated to the upcoming Moon flight. In this edition, prominent Soviet science popularizers and science fiction writers shared their visions of the upcoming space exploration. The magazine made a prediction: the first artificial satellite would be launched in 1970. However, the authors were mistaken – the space era began much earlier.

In 1953, Sergei Korolev, the chief designer of Soviet rocket technology, discussed the concept of a satellite. This was during the early stages of development of the R-7 intercontinental rocket, which experts believed had the potential to achieve space travel.

On May 26, 1954, Korolev submitted a report titled “On the Artificial Earth Satellite” to the CPSU Central Committee and the Council of Ministers. Unfortunately, the response was negative as the committee prioritized the development of a combat rocket capable of reaching America. Research on satellites was not a priority at that time. However, Korolev remained hopeful and sought support from the Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

On August 30, 1955, a meeting was held in the office of the Chief Scientific Secretary of the Presidium of the USSR Academy of Sciences, Academician Topchiev. This meeting brought together top experts in rocket technology, including Sergei Korolev, Mstislav Keldysh, and Valentin Glushko.

During the meeting, Korolev proposed the establishment of a special organization within the USSR Academy of Sciences. This organization would be responsible for developing a program of scientific research using a series of artificial Earth satellites, including satellites with animals on board. Korolev emphasized the importance of manufacturing high-quality scientific equipment and attracting leading scientists to participate in this endeavor.

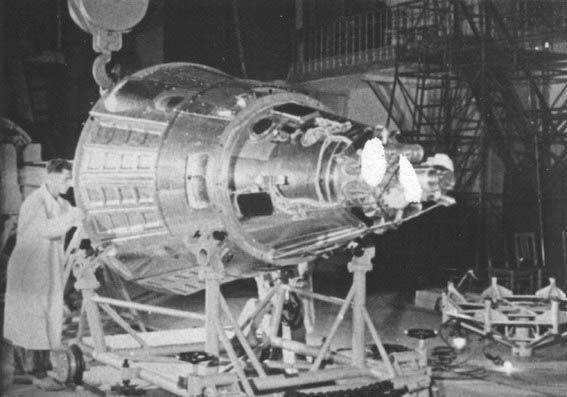

Object “D” – a space laboratory. Originally intended to be the first Soviet satellite, it ended up being the third.

Upon receiving the long-awaited decree, Korolev wasted no time in putting his plans into action. He established a dedicated department within his design bureau OKB-1, tasked with the development of artificial satellites. Following Keldysh’s suggestion, the department worked on multiple variations of Object D, one of which included a container carrying a “biological cargo” – a test dog.

Sergei Korolev closely monitored the progress of his American counterparts and harbored concerns that they might surpass him. Consequently, shortly after the triumphant launch of the “R-7” rocket on September 7, 1957, the chief designer assembled the team responsible for satellite design and suggested a temporary pause in the “Object D” project, in order to hastily develop a small, lightweight satellite.

"The initial satellite” ("PS-1") was the groundbreaking achievement.

Mikhail Khomyakov and Oleg Ivanovsky were given the responsibility of overseeing the creation and production of "PS-1" ("Simple Satellite One"). Mikhail Ryazansky came up with innovative signals for the transmitter. Sergei Okhapkin and his team designed the rocket’s head fairing, which provides protection against environmental factors.

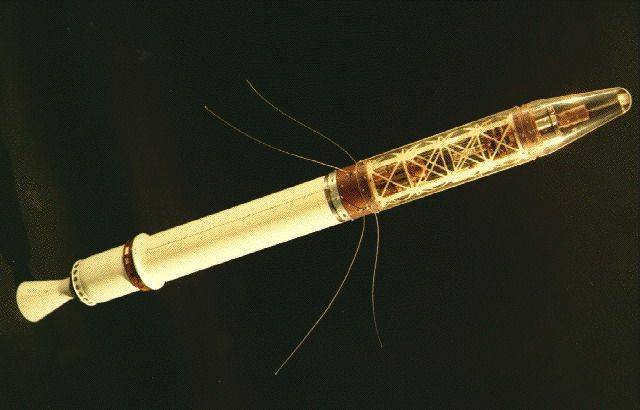

The diagram shows the PS-1 from a general perspective.

The diagram shows the PS-1 from a general perspective.  This is a poster titled “The First Artificial Earth Satellite” from 1958.

This is a poster titled “The First Artificial Earth Satellite” from 1958.

It was determined that two radio transmitters with frequencies of 20.005 and 40.002 MHz would be installed inside the satellite. The satellite was made up of two half-shells connected by 36 bolts and docking spars. The rubber gasket provided a tight seal for the joint. The satellite had the appearance of an aluminum sphere with a diameter of 0.58 m and was equipped with four antennas. Power for the satellite’s onboard equipment was supplied by electrochemical current sources, specifically silver-zinc batteries, which had a lifespan of 2-3 weeks.

PS-1’s internal structure.

The development of the Soviet satellite was not kept confidential. Even half a year before the historic launch, an article titled “Artificial Earth Satellites” by V. Vakhnin was published in the popular magazine “Radio”, which provided information on the orbital parameters of future Soviet satellites and the frequencies that radio enthusiasts should use to catch their signals.

This is fascinating

- The anniversary of the launch of Sputnik-1 is celebrated in Russia as the Day of the Space Forces.

- To commemorate the launch of Sputnik-1, a 99-meter-tall monument called the Conquerors of Space was constructed in Moscow. It resembles a rocket taking off with a trail of fire behind it and is located near the VDNKh metro station.

- The Soviet government gifted a model of Sputnik-1 to the United Nations, which is now displayed at the entrance of the UN Headquarters Hall in New York.

- On November 4, 1997, cosmonauts from the Russian orbital station Mir manually launched a 1:3 scale model of Sputnik-1 (RS-17, Sputnik-40) into space. This model was created by Russian and French students to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the first satellite launch.

- In 2003, a replica (doubler) of Sputnik-1, which was originally created in 1957, was purchased through an eBay auction. This particular copy had previously been presented as an educational display at one of the institutes in Kiev. It is widely believed that four duplicates of the “Simplest Satellite” were fabricated in advance of its momentous launch.

Sergei Korolev stood at the launch site of the Baikonur Cosmodrome.

On September 20, 1957, a meeting of the special committee responsible for the satellite launch took place at Baikonur, during which all departments confirmed their preparedness for the mission. Finally, on October 4, 1957, at 22:28:34 Moscow time, a brilliant flash illuminated the Kazakh steppe at night. The M1-1SP launch vehicle (a modified version of the R-7 rocket, later known as Sputnik-1) soared into the sky. Its flame gradually weakened and soon became indistinguishable against the backdrop of the starry night.

295 seconds after the launch, PS-1 and the central unit of the rocket, weighing 7.5 tons, were placed into an elliptical orbit with an altitude of 947 km at apogee and 288 km at perigee. At 314.5 seconds after liftoff, the satellite separated and started transmitting a signal: “Beep! Beep! Beep!”. The spaceport captured the signal for two minutes, and then the satellite disappeared over the horizon. Experts rushed out of their shelters, cheering and applauding the designers and military personnel. And on the very first orbit, the TASS message announced: “Thanks to the tremendous efforts of research institutes and design bureaus, the world’s first artificial satellite was created. On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union successfully launched the first satellite.”

The R-7 rocket is getting ready for takeoff.

The R-7 rocket is getting ready for takeoff.  The R-7 rocket is being launched.

The R-7 rocket is being launched.

When the head fairing and the last stage of the launch vehicle were separated from the “PS-1” (as seen in a frame from the training movie), it was a significant moment.

Initial observations revealed that the satellite had entered orbit with an inclination of 65.1 degrees and a maximum distance of 947 km from the Earth’s surface. Each revolution around the Earth took the satellite 96 minutes and 10.2 seconds.

At 8:07 p.m. New York time, the RCA radio station in New York successfully received signals from the Soviet satellite. Soon after, the news was broadcasted on radio and television throughout the United States. NBC Radio even invited Americans to “tune in to the signals that marked the beginning of a new era.”

Another interesting aspect of the historic launch is the presence of a fast-moving star that appeared in the sky after October 4, 1957. Many people believe that this star was a visually observable satellite. However, the reflective surface of the PS-1 was actually too small to be seen with the naked eye. What people were actually seeing was the second stage of the rocket, which entered the same orbit as the satellite and was visible from Earth.

According to official records, the PS-1 remained in flight for a total of 92 days, from October 4, 1957, to January 4, 1958. During this time, it completed 1440 revolutions around the Earth and traveled approximately 60 million kilometers.

Photograph of the spacecraft known as “PS-1” during its orbit above Melbourne.

Nevertheless, there is proof that it descended into the dense layers of the atmosphere and disintegrated slightly earlier – on December 8, 1957. It was on this very day that a man named Earl Thomas discovered the remnants of a burning spacecraft near his residence in Southern California. Further analysis revealed that these remnants were composed of the same materials that constituted the PS-1 satellite. Presently, these fragments are exhibited at the Beatnik Museum in close proximity to San Francisco.

It is possible that these remnants are from the debris of the initial satellite that crashed in the United States.

A news article published by The New York Times discussed the remarkable launch of Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite. This event sent shockwaves across the globe, particularly in the United States. It was a profound moment for Americans as it shattered their belief of being ahead in every aspect of life, as the “potential enemy” had surpassed them in a crucial field. The New York Times highlighted the irony by stating, “Ninety percent of the talk about artificial satellites of the Earth came from the United States… As it turned out, 100 percent of the business came from Russia…” This realization was not only unsettling but also incredibly alarming!

In his book “Dance of Death,” acclaimed author Stephen King, known as “The King of Horror Movies,” confessed that the news of the Soviet Union successfully launching a satellite into orbit was the most jarring experience of his youth.

The level of fear was so intense that during the early days of October 1957, some Pentagon officials even suggested the extreme measure of “closing the sky” by deploying large quantities of scrap metal into orbital altitudes. This scrap metal would have included items such as balls from bearings, nails, and steel shavings, effectively preventing any space launches. This little-known aspect of the history of astronautics highlights the initial perception of Americans that space was exclusively their domain. They were unwilling to entertain the notion that anyone else could lay claim to it.

In reality, the United States had the potential to become the first dominant force in space.

Poster “Soviet Man-Made Earth Satellites” (1958).

If nobody considered it before World War II, then following the war, influenced by the achievements of the Third Reich’s rocket scientists, United States leaders seriously contemplated a fresh “strategic foothold.” With the help of the documents and experts acquired from Germany, the Americans were able to swiftly catch up in ballistic missiles and, as a result, lay the groundwork for launching an ISV into space.

The U.S. leadership made a single error. They should have placed their trust in the expertise and talent of Wernher von Braun and embraced the “Orbiter” project, which promised to launch the first satellite by the end of 1956. It is highly likely that the German designer would have been able to deliver on his commitments, ultimately granting the U.S. the coveted “right of ownership.”

What would have transpired? Only one aspect, albeit the most significant one, would have been altered. By establishing their presence in outer space and securing a crucial priority, the U.S. would have been less inclined to engage in a space “race” that demanded substantial financial investments. However, an endeavor to “catch up and surpass America” in the realm of space could have resulted in Soviet cosmonauts not only becoming the first to orbit the Earth but also landing on the Moon. This would have led to a profound transformation in the history of space exploration.

The start of a Soviet satellite sparked a competition in space exploration, which the Americans triumphed by successfully reaching the Moon.

It is impossible to determine whether individuals would have been more content in such a world, but that is inconsequential. Ultimately, it is irrelevant because the Soviet satellite was the catalyst for the space age, and its resounding signals caught the attention of the entire cosmos…

Also, take a look at these articles

Why the United States Definitely Landed on the Moon

The story of the Moon’s conquest and evidence that conspiracy theories should not be given credence. This includes information from the Soviet Union.

"Time of the First": separating fact from fiction

Have the filmmakers successfully portrayed the true story of the first spacewalk? Is it accurate that the Soviet government was willing to put the cosmonauts at risk?

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky: the Pioneer of Space Exploration

While opinions may vary, there is no denying the impact that this Kaluga educator had on the field of cosmonautics.

Renowned for his work as a science fiction author and his efforts in promoting scientific knowledge, Tsiolkovsky was a member of various esteemed organizations, including the St. Petersburg Writers’ Union, the Russian Federation of Cosmonautics, the St. Petersburg Union of Scientists, the Club of Scientific Journalists, and the Association of Futurologists.

Exactly half a century ago, on October 4, 1957, there was widespread panic in the United States: the Russians successfully launched a nuclear bomb into outer space. However, it was soon revealed that the “bomb” was actually a harmless sphere measuring 58 centimeters in diameter and weighing 83 kilograms. Equipped with antennas, its sole purpose was to transmit radio signals from orbit. Despite its benign nature, the impact of Sputnik-1 on the global stage can only be likened to the detonation of a bomb.

Kaputnik!

On the 4th of October, 1957, the R-7 carrier rocket took off from Baikonur Cosmodrome (then known as the 5th research range of the USSR Ministry of Defense “Tyura-Tam”) and successfully placed the first man-made satellite of the Earth into orbit.

The satellite had a spherical shape with a diameter of 0.5 meters and was equipped with four antennas, each measuring over two meters in length (although it actually had two antennas, each consisting of two parts). It had a weight of 83 kilograms and was equipped with only two radio transmitters with power supplies, which operated for a duration of two weeks after launch.

The satellite transmitted the well-known “beep-beep” sound (which can be listened to here, for instance) at a frequency of 20 megahertz, making it easily detectable by amateur radio enthusiasts.

Interestingly enough, the American Jet Propulsion Laboratory (which was not yet NASA at that time, as it was created later) did not immediately detect it due to interference from the high-voltage wires surrounding the building. However, Henry Richter, an employee of the laboratory who was assigned to verify the alarming report of a Soviet satellite launch, was almost certain that there was no signal. Just to be safe, he decided to call his friend Bob Legg, an amateur radio operator.

Unlike the laboratory, Legg’s house was not surrounded by high-voltage lines. However, he did not have a 20-megahertz antenna. To overcome this obstacle, Legg improvised by running a wire from the receiver to the metal insect netting on the window. Surprisingly, this makeshift setup allowed him to successfully capture a signal.

90% of discussions about artificial satellites on Earth originated from the United States. However, it was revealed that 100% of the actual satellite business came from Russia. New York Times, October 1957.

America perceived the “beep-beep” sound as a significant threat. The country had been discussing space conquest for years, and artificial satellites had already been developed. Now, it became clear that the supposedly technologically backward USSR had surpassed the United States.

Furthermore, the potential enemy’s spacecraft, orbiting the Earth every hour and a half, silently flew over American territory, impervious to any weapon. The International Herald Tribune captured the Americans’ state of mind with the gloomy headline “Kaputnik!”.

Delight and its Consequences

The entire world has committed to memory the Russian term “sputnik”. It has been adopted into numerous European languages and is universally understood without the need for translation (simply observe the links below).

The world was not only frightened but also filled with elation: for the first time, a human-made device ventured into space, reaching an altitude of 947 kilometers (the apex of its orbit), surpassing the previous record held by a German artillery shell, which stood at a mere 48 kilometers. The Sputnik fashion trend emerged in America, Sputnik cocktails were introduced in Western Europe, and rock and roll enthusiasts danced the Sputnik dance.

Importance in the Field of Science

The Soviet Union successfully deployed the satellite as part of its participation in the International Geophysical Year initiative. By emitting radio waves at two distinct frequencies, the satellite provided valuable insights into the characteristics of the upper ionosphere. Prior to this mission, scientists were limited to analyzing radio signals reflected from Earth to study the lower ionosphere.

Sputnik-1 did not carry any other scientific equipment. It was more of a successful experiment, a symbol of the dawn of the space age, and while nowadays satellites are launched by schoolchildren, back then it was an unprecedented leap forward.

The importance of the experiment was recognized by the Nobel Committee, which in 1958 inquired of the USSR leadership who was the creator and chief designer of the device. Nikita Sergeyevich responded that the entire Soviet people were the authors of this new technology. However, the Nobel statutes did not allow for awarding the prize to an entire nation, so the engineers were left without a reward.

One of the primary architects behind the creation of Sputnik-1, Boris Chertok, who served as Sergei Korolev’s deputy, is still alive and thriving. Despite being 95 years old, he continues to contribute as a consultant at the Energia Corporation.

Golden Jubilee

The world is joyously commemorating the fiftieth anniversary on a grand scale. The streets of Moscow are adorned with vibrant banners paying tribute to the satellite, while captivating video clips are being displayed on street TV screens. Today, a monument honoring Sputnik-1 was unveiled in Korolev.

A radio expedition, orchestrated by Radiodelo magazine and Roscosmos, has commenced at Baikonur. The memorial radio station incessantly broadcasts the UP50 SAT signal, prompting numerous radio enthusiasts from different nations to respond.

To mark this momentous occasion, Russia, the Czech Republic, Kazakhstan, and the Cook Islands have issued special commemorative coins featuring the satellite’s image.